-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Scots revealed to be biggest Trump fans in western Europe

In a rather surprising development, it transpires that Scottish people are Donald Trump’s biggest fans in Europe. A Norstat poll for the Times has revealed that support for the US presidential candidate is higher north of the border than in the rest of the UK – and indeed western Europe. Who’d have thought it, eh?

According to the survey, a quarter of Scottish adults back the former president for the win this week – while, of the rest of the country, just 16 per cent would throw their weight behind the ex-businessman. Italy is closest behind the Scots in terms of Trump hype, with 24 per cent of Italians hoping the Republican candidate sees victory. Meanwhile 17 per cent of Spaniards back Trump, while the ex-president has the support of 15 per cent in France, 14 per cent in Germany, 13 per cent in Sweden – and just 7 per cent in Denmark. How very interesting.

Mr S reckons the presidential candidate would be rather pleased to hear of his support among Scots given the pride he has for his Scottish links. His mother Mary Anne MacLeod was born on the Isle of Lewis and the US presidential hopeful currently owns one golf club north of the border with big plans to build another in Aberdeenshire next year. Not that the SNP government will be quite as thrilled about the stats – given just last week Trump waded into the independence debate by proclaiming about the Union: ‘I hope it stays together. I hope it always stays together.’ Cover your ears, Nats…

More than that, First Minister John Swinney’s decision to endorse Kamala Harris last week sparked outrage across the country, and even prompted Trump to label the move an ‘insult’. It seems it was a rather controversial choice among separatist supporters too – given today’s Norstat poll has revealed almost a fifth of SNP voters hope the Republican soars to victory. There are now just days to go before the result is announced and America meets its new president. Tick tock…

Why does ITV hate Trump?

It would be consoling to think that the BBC, alone among our supposedly unpartisan TV news providers, is guilty of hopelessly biased coverage of the US presidential election. This would conform to the increasingly popular notion that Auntie is in a place beyond redemption, unique in its iniquities.

That notion may be true, but it is not true of its US election coverage. All of the news providers have been biased and the BBC is probably one of the least egregious of offenders. It would seem to me that all the broadcasters broadly concur that a second Trump presidency would be a disaster for the US, for democracy and for the world and that therefore the normal rules of balance are not applicable. They demonstrate this bias in the following four ways:

- Story selection.

- The tone of reporting.

- Choice of interviewees.

- Editorial comment

I have not watched enough of ITV’s coverage to generalise that it is by far the worst, but the edition of its Friday night News at Ten – which seemed to be presented by a great white shark with a quiff – was relentless in its bias. Gaffes made by the Democrats were explained away, those by Donald Trump not so.

It was implied – indeed, stated – that Trump had wished upon Liz Cheney a firing squad which would shoot her in the face. This was a pretty grotesque misrepresentation of Trump’s point, which was that Ms Cheney would be less hawkish if she herself had to face the consequences. His point, nastily expressed for sure, did not seem a terribly complex allusion to unravel, but even the notion that it might possibly be an allusion was ignored: Trump had said she should be shot in the face, end of.

The package which followed contained all the signifiers of casual, unthinking, bias. So, for example, a voter who professed himself a Trump voter was asked a subsidiary question along the lines of ‘don’t you worry that he is a despotic orange-faced right wing maniac?’ (or words to roughly that effect), while his neighbour, who was for Harris, was asked no subsidiary question (such as ‘don’t you worry that she was a fabulously useless VP with the IQ of a bottle of tomato ketchup?’).

On the same evening, a little later, Newsnight – presented by the excellent Katie Razzall – gave us an admirably weighted debate about the same issues. I mention this not to exonerate the Beeb, which in its straight news coverage does display a marked tilt towards Harris, but to suggest that it is not the worst offender. This bias is almost universal on our screens.

Should GPs make a profit?

The Budget has started a fight between the government and GPs. As is often the case with doctors, that fight is about money, but there is also something even more valuable at stake: the proper public understanding of general practice and the NHS.

When I ran a thinktank, I kept a list of things I wished the public understood about government and public policy. Top of the list was: ‘No, your state pension isn’t funded by your own National Insurance payments – it’s funded from the taxes of today’s workers.’

Health got lots of entries on the list too:

- ‘The NHS’ isn’t one big organisation; it’s lots of small and medium ones.

- The British Medical Association isn’t a medical authority seeking better care for patients – it’s a trade union seeking more money for doctors.

- GPs aren’t part of the NHS; they’re private contractors who make a profit from providing healthcare.

Thanks to Darren Jones, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, that last fact might be reaching more of the public. The reason is the government’s plan to raise employers’ National Insurance rates, effectively taxing them more for employing workers.

Public sector bodies are being spared that rise but, as things stand, private organisations aren’t, even if they provide vital services to the public. That list includes charities, care home providers and GP partnerships.

‘GP surgeries are privately owned partnerships and not part of the public sector and will therefore have to pay,’ Mr Jones said last week, with the admirable frankness that makes him a politician worth watching very closely in the years ahead.

Mr Jones’s words have made the British Medical Association unhappy. Some would consider the BMA’s complaint as evidence in itself that Mr Jones is doing the right thing, but the point still bears a little exploration.

GPs are not part of the NHS and never have been. Indeed, they almost prevented its creation. In January 1948, some 84 per cent of GPs in the BMA voted against the new service.

And when the NHS was established, GPs stayed outside it, preferring to organise themselves via partnerships. These are private organisations that are paid by the NHS to dispense services. Partnerships are not, legally speaking, companies but are private entities owned by individuals who share any profits they make. The average GP partner made £140,000 in 2022/23, roughly £13,000 more than the previous year. (Non-partner GPs earn lower salaries, but pay comparison is tricky because they’re more likely to work part-time.)

Is the partnership model a good idea? Let’s ask a doctor – Tom Riddington, a (non-partner) GP in Dorchester.

Dr Riddington says:‘Partners are contractors, not NHS employees. We are, to be blunt, incentivised to provide the cheapest possible care that fulfils our obligations to our patients.’

What does that look like in practice? Some of this comes down to drugs. Some GP practices directly administer drugs, including vaccines and contraceptives, among others. They buy these drugs at the lowest possible cost then get paid a standard rate by the NHS for administering them.

The margins available here are quite high.

According to specialist medical accountants at Page Kirk, ‘a typical non-dispensing GP practice would expect a drug profit of around 25–30 per cent, while dispensing practices can aim for 30–35 per cent.’

Profits create incentives. Are the incentives here working in favour of patients, or taxpayers?

In 2021, a study at York University found that GPs who stood to make a profit from medicines tended to prescribe more of those drugs to patients:

Our analysis provides evidence that English GPs modify their prescribing behaviour when permitted to dispense medications in ways that are consistent with a profit motive. These behavioural differences are unlikely to be explained by differences in the healthcare needs of their local patient populations.

None of these things are secret. The nature of GP partnerships and the financial framework in which they operate are facts knowable to the public, but in reality almost never discussed. Partly that’s because they’re pretty complicated and often boring. Partly it’s because GPs’ representatives have been very careful to keep quiet about the financial reality of ‘family doctors’ as profit-seekers.

Personally, I’m quite relaxed about the idea of people and organisations making a profit from providing public services: I think the incentive to make money can, in the right framework, deliver better outcomes for service-users and taxpayers.

But I’m also very committed to political debate based on facts, and the fact that GP partnerships are private contractors outside the NHS is almost always absent from public debate about healthcare. The BMA appears to calculate that voters don’t really like the idea of doctors making money out of treating them, so it keeps quiet and hides behind the sacred NHS brand.

The incentive to make money can, in the right framework, deliver better outcomes

If more voters knew about GPs making a profit from treating them, would doctors’ political strength in negotiations with government change?

It’s a thought to ponder, especially for the BMA as it takes on Mr Jones. A minister armed with facts and the willingness to use them could be a dangerous opponent.

Especially if this fight leads to a bigger conversation about the relationship between GPs and the NHS. A few years ago, there was chatter in healthcare circles about the case for effectively nationalising general practice, ending the partnership model and bringing GPs into salaried employment.

Wes Streeting, now health secretary, looked closely at such plans before backing away a little – after fierce objections by the BMA – but the idea surely hasn’t gone away forever. Especially since Labour has an urgent need to get better value for money in healthcare to help justify its tax increases.

It’s also worth noting that a few doctors, such as Tom Riddington, are in favour of nationalisation, arguing that it would give doctors clearer incentives to serve patients.

The BMA’s case against GP partnerships paying higher National Insurance is that doing so might make them financially unviable – by eroding their profits. The more clearly that argument is heard by the public, the greater the chance that voters start to take a more informed interest in GP finances. It would be no surprise if this means GP nationalisation returns to the political agenda.

Labour’s tuition fee U-turn

Dear oh dear. It now transpires that Starmer’s army will increase university fees in line with inflation from September next year, as announced by Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson in the Commons today. It’s the first hike to tuition fees in eight years after university payments have remained frozen at £9,250 a year since 2017 – and accompanies growing concern about the financial state of the country’s higher education institutions.

The move, which Phillipson says is the ‘first step’ to reform of the sector, comes after Russell Group universities complained that the tuition fee cap means that they make a £4,000 loss per UK student – and will be accompanied by a slight increase in maintenance loans to help students with living costs. However Steerpike remembers that raising university fees has not always been a Labour policy. In fact, when Sir Keir Starmer ran to be party leader, the politician insisted at the time that he wanted to abolish payments altogether. Just four years ago, the Labour MP ran on a campaign to ‘support the abolition of tuition fees and invest in lifelong learning’. So much for that promise, eh?

And it’s not just Starmer under scrutiny over the U-turn. Last year, the now-Education Secretary wrote an op-ed for the Times in which she promised university leavers a Labour government could ‘reduce the monthly repayments for every single new graduate’, adding that she hoped to ‘[put] money back in people’s pockets when they most need it’. With economists predicting that raising fees in line with inflation over the next five years could lead to costs reaching around £10,500 Mr S reckons prospective students and their families will not be best pleased by this volte face. After the outrage sparked by ex-Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg’s infamous U-turn on the issue back in 2012, Starmer’s Labour lot could be in for a rocky ride…

How Germany became the sick man of Europe

Vertrauen ist gut, Kontrolle ist besser – trust is good, control is better – is a popular German saying. It’s also the state’s motto for overseeing Europe’s biggest economy, which is now being run into the ground. Germany’s economy is officially expected to shrink in 2024 for the second year in a row. Berlin’s Social Democratic Chancellor Olaf Scholz and his Greens Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck, who are fighting for their political lives as their coalition crumbles around them, are to blame.

Only one German sector is growing: the state. Government consumption grew by 2.8 per cent from mid-2023 to mid-2024. Dealing with bureaucracy costs German business €67 billion (£55 billion) per year, says Berlin’s Federal Justice Ministry.

Germany is a country in which it is not always easy to do business

Scholz’s answer? Expand the state, more debt, redistribute more money and, his party’s all-time greatest hit: tax the rich. Germany already has the second highest taxes in the OECD club of industrial nations. The plan could raise the top income tax rate to as high as 56 per cent from the current 45 per cent, German media reports. The SPD calls this a tax on the top one per cent, yet it’s not just aimed at millionaires – it kicks in for those earning over €280,000 (£215,000). Final details will be unveiled for the SPD’s re-election campaign next year.

Scholz’s latest antics are to condemn a possible takeover of Germany’s stumbling Commerzbank by Italy’s far more successful UniCredit bank as ‘unfriendly attacks.’ Petty nationalism trumps creating European banking champions.

While Germany remains Europe’s largest economy, the truth is that this is a country in which it is not always easy to do business. In the 25 years I’ve been running our family forestry business in eastern Germany, the biggest problems haven’t been markets or weather, but rather the grasping hand of the German state. These troubles are structural and go back to German reunification in 1990.

I bought our first forest from the state during privatisation of ex-communist East German land. Big mistake. The contract said I needed to have my main residence ‘close by’ the forest. Nowhere was it defined what this meant in miles. I ended up being dragged to court by the BVVG privatisation agency, which belongs to the German Finance Ministry, over claims that my home was too far away. The legal circus lasted five years and cost me tens of thousands of euros before I eventually won.

This year, we again went to battle with the German state – and lost. Adjoining a forest we own in Saxony-Anhalt state are 28 hectares of meadow. Our son is more interested in beef cattle than in trees, so the plan was to buy the meadows and start raising grass-fed beef. After years of negotiating, we signed a contract to purchase the land from a neighbour. ‘Not so fast!’ the state said. When it comes to farmland, Germany is a command, state-planned economy. With no plausible explanation, the county government not only blocked the sale to us but awarded the land to another farmer. This wasn’t some poor, struggling smallholder but rather one of the big landowners in the region.

Such stupidities pale compared to the Scholz-Habeck bungling of what they claim is their top priority: building wind turbines and solar parks to speed Germany to net-zero nirvana. But they are revealing of the trouble of doing business in Europe’s supposed economic powerhouse.

The Scholz-Habeck government was lightning fast when it came to shutting down Germany’s last nuclear power stations. So fast that Habeck may have ignored expert voices warning against it. This is now the subject of a parliamentary investigation in the Bundestag.

The big problem is that Germany is proving unable to speed up the construction of new wind parks and the high-tension lines needed to shift electricity around the country. In the first half of 2024, just 250 new windmills were built in Germany. That’s only a fraction of the year’s target.

I’ve been trying to build a wind park with my neighbours in a forest in eastern Germany since January 2021. It’s been approved by the town council and a year-long environmental assessment found scant evidence of conservation conflicts. I have signed contracts surrendering land to be reforested as compensation for the footprint of the windmills. You would think all is good. But you would be wrong.

Berlin will soon pay a heavy price for this sluggishness on planning for the future

Germany’s Energiewende, or energy transformation, is running head-on into a wall of state bureaucracy, even in sparsely populated eastern Germany. As the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper warns: ‘The success of the energy transition in Germany will be decided in the east.’ But the German state doesn’t seem to have woken up to the fact.

Earlier this year, I was told that the wind park was too big and ordered to reduce it from 15 to five windmills. Other state agencies soon weighed in. A conservation official indicated he is against windmills in forests – even though they are legal in Brandenburg state – and would oppose the wind park. Then the historic monument agency claimed the wind park might detract from sightlines at two, historically trifling castles.

Laws that Scholz and Habeck have passed, which they claim will speed up renewables, don’t seem to concern the officials tasked with giving the go ahead to wind farm projects. But Germany will soon pay a heavy price for this sluggishness on planning for the future.

Where the country gets its energy from in the years, and decades, to come will become a huge problem for the world’s third biggest industrial economy. Coal-powered plants are being rapidly closed. The lignite electricity plant near my woods – that’s been running 24/7 all year – will be shuttered in 2028.

Habeck’s suggestion on dealing with energy misery – if you can believe it – is to ration electricity. German industry should produce only at peak electricity periods and electric cars and heat pumps, that he insists home owners install, may have their power cut off.

A poisoned cocktail of massive over-regulation, high energy costs and a lack of skilled workers has again made Germany the sick man of Europe

‘This is a great idea for, say, bakers who bake bread at night. Shall they wait until the morning when the sun rises?’ asks Jörg Dittrich, head of the German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (ZDH).

A poisoned cocktail of massive over-regulation, high energy costs and possible future energy shortages, lack of skilled workers and generous social welfare for those who don’t – or won’t – work has again made Germany the sick man of Europe.

Deindustrialization is real. German companies are closing factories at home and fleeing the misery. Volkswagen plans to close at least three of its ten plants in Germany and will downsize the rest, according to the company’s works council. There will be wage cuts and some divisions will be moved abroad, says the works council. VW and Mercedes-Benz are investing billions of dollars in the US. Chemicals giant BASF is doing the same, flanked by a ‘permanent’ downsizing of its Ludwigshafen headquarters, along with thousands of job cuts in Germany.

These aren’t isolated examples: around 37 per cent of German companies are considering cutting production or moving abroad, says a survey by the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce.

Meanwhile, US chipmaker Intel in September announced a two-year delay for a planned €30 billion (£23 billion) chip plant in eastern Germany. This is despite the fact that Scholz’s government had pledged €9.9 billion (£8.3 billion) in subsidies.

Scholz is marching Germany into decline

Despair over Germany as a place to do business also led me to start bailing out. I bought a forest in the US southeast state of Georgia in 2017. Georgia is a centre of American forestry. It has light-touch regulation. When I deal with Georgia bureaucrats, it’s still a shock to discover that most want to help me succeed. Selling up in Germany and shifting to the US makes business sense. In Georgia, we do what tree farmers increasing cannot do in Germany: we simply produce what the market wants.

But creating guardrails and getting out of the way so an industry can produce for the market is foreign to Scholz and Habeck. They’re too busy regulating, banning, subsidising, magically thinking about electricity as they close nuclear and coal plants, and fantasising about post-industrial net-zero.

Any responsible head of government would look at Germany’s misery and say ‘this cannot go on’. He’d sack at least half his cabinet and place every sacred policy cow on the table and slaughter those that aren’t delivering. But there’s no sign Scholz will do this.

Chancellor Scholz is responsible for Germany’s failure to rebuild the military. He’s responsible for Berlin’s failure to play a leadership role in Europe. And now he’s to blame for the tanking economy. The gentleman’s not for turning, even as he marches Germany into decline, debacle and irrelevance.

Avanti dilettanti!

A fragile democracy has bloomed in Botswana

There’s been a momentous election in Africa, Botswana to be exact. Not heard about it? Don’t be surprised. The British and US media have all but ignored the story or got it wrong in the run-up. Even the BBC barely mentioned it though they bang on about Israel to such a degree you’d think the war was in Guernsey instead of Gaza.

On 30 October, Botswana held a general election as they have every five years since independence from Britain in 1966. Of all the countries in Africa, it’s the only one that’s never had a coup or a period of autocratic rule. But since 1966, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) has won every time.

80 per cent of adults in Botswana believe there is corruption at the highest level of government

No surprise given a gerrymander that works in their favour and scant attention paid to the vote itself. In Zimbabwe, Britain goes rightly moggy over rigged elections. And there’s enormous focus on South Africa, Kenya, even Nigeria. So why not here? Because on every motion of substance at the UN, including all the resolutions against Russia over its war in Ukraine, Botswana votes with Nato, whereas South Africa and much of the region abstains.

A momentous election? Yes, because this time the ruling BDP came fourth, with just four seats out of the 61 in parliament. President Mokgweetsi Masisi, 63, was standing for a second and final term, as allowed by the constitution, and had a comfortable majority from the previous election in 2019. Masisi’s rival was Harvard lawyer and human rights activist Duma Boko, who had persuaded four opposition parties to group themselves as the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC).

I was in Botswana last month, and it was clear to me the government was in trouble. Of all the people I spoke to, not one said they intended to vote for the BDP. And they believed the system was rigged.

Michelle Gavin was US ambassador to Gaborone from 2011 to 2014 and is now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in Washington. A day before the election she penned an excellent take, explaining how polls show 80 per cent of adults in Botswana believe there is corruption at the highest level of government and unemployment among the youth is at a record high.

The former ambassador’s prediction? A ‘BDP victory that returns President Masisi to office for another term,’ she wrote, was ‘the most likely outcome.’

How did she and the establishment get it so wrong? Here’s how Boko did it.

Boko had run before. In 2019, his UDC lost and he alleged there’d been ‘massive electoral discrepancies’. The ruling party used state-owned radio and television for propaganda. Journalists who criticised the government found themselves barred from briefings.

So Boko hatched a plan. This time around, his party recruited thousands of volunteers who would stand guard at every polling booth, keeping the boxes in sight until they were opened after which they watched the entire count and logged the numbers – something the British, US and EU observers should have been doing all these years.

Out of Masisi’s 38 MPs, 34 lost their deposit and the UDC has a majority in the house. The president conceded before the count was finished. Botswana is a member of the Commonwealth, so you’d think there’d have been more coverage – but few seemed to care. Like Michele Gavin, those who did assumed history would repeat itself.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and British Foreign Secretary David Lammy were quick to send their congratulations to the new leader. Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa did the same. But everyone appeared to be in shock.

In the weeks leading up to the vote, I spent a lot of time with the man who is now President Boko of Botswana. He is suave, sharp and swore me to secrecy on his party’s plan to micro-monitor the vote. In 40 years at this game, I’ve never revealed anything told to me ‘off the record’ and I kept my word.

Even I was amazed at how well it worked out and the utter collapse of Masisi’s once-invincible party. So what comes next?

Botswana’s GDP is dominated by diamonds and, thanks to factory-made stones, the real things have crashed in value. Most of the trade is handled by De Beers, which is in turn owned by the London-based company Anglo American. Some months ago, the Aussie mega-firm BHP tried to buy that company for £38 billion but were knocked back. Anglo then announced it would hive off De Beers and a few other assets. In 2018, 2 per cent of US engagement rings carried a factory gem; now it’s close to half, and growing. Selling De Beers might be akin to flogging a VHS tape. But President Boko hopes to assemble a global consortium, rescue the brand and headquarter it in Gaborone.

His other problem is youth unemployment. The streets of the capital are rife with youngsters looking for work. He plans to diversify the economy and Britain should help where it can with know-how and investment. The youth will only stay quiet for so long and if we want this new-found democracy to thrive, then riots are not the answer. The euphoria this change has brought to town is real, but people can’t eat it.

2024 hasn’t been a good year for ‘legacy’ parties. In August, the African National Congress lost in South Africa and have been forced into an awkward coalition that trembles with every vote in parliament. Then it was Botswana’s turn.

On 27 November, Namibia will decide whether to keep the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) after 30 years in power. SWAPO has an 11-seat majority; in 2019 they lost 14 seats and another drop like that will see them out of office.

If you’ve read this far, at least you won’t be able to say you didn’t know the election in Namibia was happening. Let’s just hope the media will tear itself away from the Middle East long enough to report it.

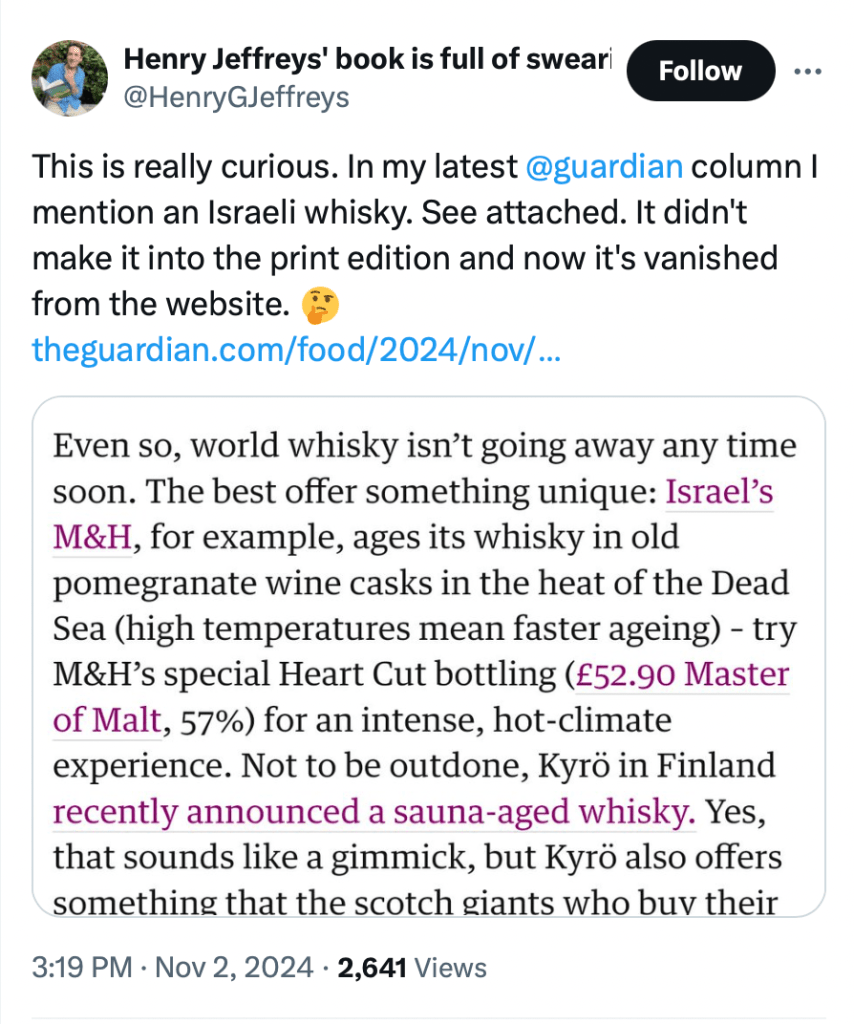

Guardian removes Israeli whisky reference

Well, well, well. It seems that the Guardian, the self-proclaimed bastion of ‘clarity and imagination’, has been acting rather censoriously of late. It transpires that, in a column navigating the world’s great whiskies by wine critic Henry Jeffreys, a reference to an Israeli single malt whisky was first removed from the print copy – before subsequently being deleted from the online version. How very curious.

Taking to Twitter to point out the baffling omission, Jeffreys posted a screenshot showing which clearly showed his reference to Israel’s M&H beverage. ‘Even so, world whisky isn’t going away any time soon,’ the wine critic had written. ‘The best offer something unique: Israel’s M&H, for example, ages its whisky in old pomegranate wine casks in the heat of the Dead Sea.’

Yet now the online copy is distinctly different. It reads: ‘Even so, world whisky isn’t going away any time soon. The best offer something unique: Kyrö in Finland recently announced a sauna-aged whisky.’ How very bizarre.

It’s not the first time the Grauniad has made rather notable deletions after publication. Only last month, Steerpike revealed that the paper had removed a controversial 7 October review after it received backlash over its author’s suggestion the film had portrayed Gazans as ‘testosterone-crazed Hamas killers’. While it was certainly quite the take, the paper could have defended the publication of the piece – or acknowledged its flaws – and yet it seems this beacon of transparency opted for neither option.

Mr S has approached the newspaper for comment on the latest edit of Jeffreys’s piece, but the Guardian are yet to respond. Stay tuned…

Heads will roll after Spain’s flooding catastrophe

Spain’s King and Queen were pelted with mud yesterday when they visited Paiporta, epicentre of the flood disaster zone in the Valencia region. Over two hundred people have died in the flooding, dozens of them in Paiporta; more are thought to be trapped and, by this time, surely dead in underground garages and car parks. Local people are furious that the authorities were slow to issue flood warnings when the rains came last Tuesday and then very poor at coordinating what has turned out to be a seriously under-resourced relief effort.

Locals seized the opportunity to vent their feelings of abandonment and desperation, chanting ‘Murderers’ and hurling slurry at the group

Many people are still without electricity, gas and water. Streets remain blocked by huge piles of cars. Some locals say that volunteers bringing in food and other supplies have been of more help so far than the police or army.

Protocol requires that the head of the regional government accompanies the monarch on official visits and Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s prime minister, who had not yet visited the disaster area, also decided to join Felipe and Letizia. Unsurprisingly, locals seized the opportunity to give vent to their feelings of abandonment and desperation, chanting ‘Murderers’ and hurling slurry at the group.

As the situation became increasingly volatile, Carlos Mazón, the regional leader, and Sánchez were quickly extricated by security officials. But King Felipe and Queen Letizia stayed for over an hour to listen, trying to console local people. When his escort attempted to shield Felipe with an umbrella, he insisted that they take it down so that he could meet people face to face. Letizia, pale, mud-spattered and apparently close to tears, could also be seen listening intently and nodding as locals shouted and screamed in despair.

Sánchez was surely right when he suggested that now is not the time to analyse negligence and allocate blame for the disaster, but that day of reckoning will soon come. Mazón is already being criticised for not declaring the flooding a ‘catastrophic emergency’ as soon as the scale of the disaster became apparent last week; that would have immediately transferred control of the situation to the central government.

In a country governed at five levels – local, provincial, regional, national and European – the distribution of powers in such extreme situations is, as Sánchez has intimated, a key problem. During the pandemic, the bureaucratic confusion caused by too much government also quickly became apparent. And problems are compounded when a left-wing central government has to deal with a right-wing regional administration: instead of working in harmony for the good of the people, politicians of both sides soon succumb to the temptation to score points.

Spain has an estimated 300-400,000 politicians; relative to population, that’s twice as many as France. The country’s politicians, while very numerous, are also seen as remote and unaccountable. And corruption is rife partly because there is so much administration. Both main parties, Sánchez’s left-wing PSOE, and regional leader Carlos Manzón’s right-wing Partido Popular, are constantly at loggerheads and mired in scandals.

In normal times, Spaniards are noticeably tolerant of their venal politicians’ ineptitude. But these are not normal times. Once the dead are counted and some semblance of normality has been restored, the political fallout will be huge. Any attempt to blame this disaster on climate change or to pass it off as a natural disaster which has to be accepted as ‘one of those things’ will be given short shrift by a furious populace. Heads will surely roll.

In the meantime, the monarchy’s popularity looks set to rise still further. Felipe, who’s 56, has done a good job during his first ten years on the throne. Taking after his mother rather than his back-slapping father, he’s seen as sober, hard-working and honest. Not surprisingly his June approval rating of 6.6 out of ten, according to IMPO Insights, is far higher than that of any of Spain’s leading politicians. The courage that he and Queen Letizia displayed yesterday will be remembered for a long time.

Starmer’s plan to stop the boats is a comical gimmick

The shiny new Downing Street operation that has come into being since the departure of Sue Gray has decreed that this is going to be ‘small boats week’. They have created a media grid with the aim of promoting the idea of Keir Starmer as a strong and authoritative leader busily coordinating measures to accelerate Labour’s plan to ‘smash the gangs’.

Rather comically, the Sun newspaper was briefed that Starmer will declare the border crisis a ‘national security issue’, announce a crack new team of investigators, hold talks with Giorgia Meloni and vow to end ‘gimmicks’. So that’s three gimmicks followed by a promise not to indulge in gimmicks. It would take a heart of stone not to laugh.

The tectonic plates of British politics are on the move

None of Starmer’s activity addresses the key driver of the illicit Channel traffic: the fact that people who illegally gatecrash their way into our country are rarely detained in jail-like conditions and almost never removed. Instead, the bulk are put up in hotels, given spending money, allowed to come and go as they please and thus able to work in the cash-in-hand economy. Ultimately they can expect to win formal permission to stay and unlock for themselves permanent access to the British welfare state and possibly the right to bring family members to join them. Such access for a young man could easily be worth £1 million over a lifetime – truly a golden ticket.

Yet Starmer and Home Secretary Yvette Cooper continue to peddle an approach to the issue which focuses exclusively on an alleged mission to destroy the very profitable people-moving gangs: all of them. The purported aim is to make sure there are no rubber dinghies available to take illegal migrants across the Channel (or more precisely, take migrants to the mid-point of the Channel from where UK Border Force or RNLI vessels provide a water taxi service into Dover).

Unsurprisingly the strategy has yet to bear any fruit: no gang has been smashed. The numbers crossing have accelerated upwards too since Starmer and Cooper took over and pulled the plug on the Rwanda removals policy, having connived in its frustration for the previous two years. The BBC today reports that in October alone there were more than 5,000 arrivals,

Yet for Starmer and Cooper it is an unconscionable sin to acknowledge that the migrants themselves have agency and are the key drivers of this trade. When he came into office in July, the Prime Minister wrote that: ‘Every week vulnerable people are overloaded onto boats on the coast of France. Infants, children, pregnant mothers – the smugglers do not care.’ The reality is that 80 per cent are young men typically paying £3,000 a pop and helping to carry the boats down beaches to the water’s edge.

But still, the policy of zero deterrence and an exclusive focus on ending the supply of boats continues. Today, Starmer announced a doubling of the budget of his new Border Security Command to £150 million – an unprecedented investment in gold braid and epaulettes that may at least be of some benefit to the British textiles industry.

Perhaps, sooner or later, a gang or two will be ‘smashed’ and Starmer will excitedly dash down to Border Security Command HQ to celebrate. But what will happen then? Anyone with a basic knowledge of economics will understand that a temporary downturn in the supply of boats will lead to higher prices for a seat in a boat, making the remaining gangs even more profitable until new gangs are drawn into the trade. It’s a demand-driven business.

One Channel migrant is currently on a murder charge in a Midlands town. Not much has been written about it. Public anger locally largely remains below the surface – a result of Starmer’s summer law and order crackdown against ‘Far Right’ agitators, no doubt. British nationals are deemed to have agency you see, even when driven half-mad with grief about the killing of compatriots.

Yet the tectonic plates of British politics are on the move. Reform’s MPs continue to highlight what they term an ‘invasion’; the Tories finally have a new leader ready to go for the throat of ‘Two Tier Keir’. The Starmer shtick – a former DPP with Action Man hair launching a never-ending stream of securocrat gimmicks – is already wearing very thin. The truth cannot be hidden from people for much longer: it is the ideological weirdness of the British left, embodied by Starmer, which facilitates the gatecrashing of our borders by ruthless and undocumented young men from other cultures.

James Dyson isn’t helping farmers

If I were president of the National Farmers’ Union I know what my first task would be today: ring up Sir James Dyson and plead with him to keep his trap shut. It isn’t that Dyson, one of the few living Britons who has set up a manufacturing business of worldwide reputation, isn’t worth listening to on the economy and many other things. But when it comes to protecting the interests of family farms – which is the NFU’s prime interest after last week’s Budget – Dyson is the very last voice you should want to hear publicly supporting your case.

Dyson is the last voice you should want to hear publicly supporting your case

For all I know Dyson may have been harbouring a latent interest in agriculture since he was a lad. He may be as passionate about growing peas as he is about designing vacuum cleaners – more so, even. But he also happens to epitomise the very target of Rachel Reeves’ decision to limit agricultural property relief (APR) to the first £1 million of assets: a wealthy individual who starts buying up farmland in late middle age. The 77-year-old now owns 35,000 acres of it. It is hard to believe that concerns about inheritance tax did not enter his head when he moved into farming.

It is not just farmland which will be affected by the changes to inheritance tax: Reeves also put a £1 million limit on the tax relief which can be claimed on business assets, which will affect thousands of small businesses. Writing in the Times today, Dyson does indeed lead on small businesses of all kinds, only later moving onto the subject of farms. But like it or not, family farms have become the face of resistance to the Budget. Having a man estimated by the Sunday Times Rich List to be worth £20.8 billion emerging as the figurehead for their cause is not helping them. Nor, by the way, is Jeremy Clarkson helping them either. There is another wealthy figure who seems to have discovered a remarkable interest in food production fairly late in life.

If the farming lobby wants to win its battle for public opinion against the Chancellor it wants to be getting before the cameras tearful men and women who have been labouring a lifetime on their 300 acre farms and who, while they might be asset-rich, are distinctly cash-poor. According to the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, 26 per cent of mixed farms in Britain made a loss in 2022/23, while 23 per cent made a profit of under £25,000. The typical victim of Reeves’ changes is hardly a barley baron. And nor will they consider themselves wealthy on the basis that they own a few hundred acres. On the contrary, their land will not have been particularly valuable until recent years, when farmland prices started to be bid up by, er, wealthy individuals looking to acquire an asset which they can use to avoid inheritance tax – and also now by bands of ‘green’ investors looking for somewhere to plant trees in order to claim carbon credits. It is those two things which have driven up farmland prices to the level at which family farms will now be caught by Reeves’ new threshold.

Reeves’ error was not to take on the super rich farmland owners – while they have a loud voice, few members of the public will want to support them. The mistake was in failing properly to come up with a mechanism which distinguishes between genuine farmers and those who have bought hobby farms for tax purposes. She should have devised a test whereby, say, farmers had to prove they or their forebears had been farming the land for at least 30 years before they could claim relief from inheritance tax. Or a system whereby the longer you had been farming, the bigger the relief. Or, say, making inheritance tax relief apply only in cases where a family could prove that farming had been it main source of income for many years.

Those are the kinds of arguments that the family farming lobby needs to be making if it is to win its case. Dyson is not the man who is going to help make them.

Watch more on SpectatorTV:

Watch: Home Secretary flounders over small boats

Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour lot are desperate to get the press and public talking about anything but the Budget this week – and so the issue of Channel crossings is where the Prime Minister is focusing his attention today. Yvette Cooper was quizzed on the airwaves this morning ahead of the PM’s speech to Interpol’s general assembly in Glasgow over Labour’s small boat plans – but the Home Secretary seemed a little uncomfortable on the specifics…

Grilled on BBC Breakfast, Cooper was asked when Labour expects to see a drop in the number of migrants crossing the Channel. ‘We obviously want to make progress as far and as fast as possible,’ the Home Secretary started, adding: ‘We know of course it does take time to get the investigators in place.’ Pushed on exactly how long the process would take, however, Cooper simply refused to say.

What I’m not going to do is what Rishi Sunak did and just set out slogans and say everything was going to be solved in 12 months, all on the basis of a slogan, because I don’t think people will take that seriously anymore.

How curious. Will the public take seriously a government that is unwilling to set timeline targets on the matter? Mr S isn’t quite so sure…

Watch the clip here:

Can Starmer stop the small boats?

It’s small boats week in government. Following last Wednesday’s Budget, No. 10 is turning its attention to the ceaseless flow of Channel crossings. Keir Starmer will use his speech at the Interpol General Assembly in Glasgow today to set out Labour’s plans to – you’ve guessed it – ‘smash’ the criminal gangs. Starmer’s remarks are certainly timely. More than 5,000 people crossed the Channel in October, making it the busiest month of the year so far. In total, 31,094 people have crossed so far this year, up 16.5 per cent on the same point in 2023 but still down 22.1 per cent on the same point in 2022.

Starmer is expected to announce that Border Security Command will get £75 million on top of an equal sum announced in September, over the next two years. It is expected to help pay for advanced maritime drones and undercover recording devices. An intelligence source unit will pay for British officers to be deployed in high-emigration nations such as Vietnam and Iraq. As well as equipment, the additional funds will pay for more staff, with 300 personnel in the Border Security Command and 100 specialist investigators. There are new powers too, with the Crown Prosecution Service able to deliver charging decisions more quickly on international organised crime cases.

The problem is that many of these measures announced today are exactly what the Conservatives were doing

The Prime Minister will tell representatives of Interpol's 196 nations that 'the world needs to wake up to this challenge' and that 'there's nothing progressive about turning a blind eye as men, women and children die.' He will declare that 'I was elected to deliver security for the British people – and strong borders are a part of that.' The accompanying No. 10 press release declares the border crossings a 'national security' issue. It's a similar phrase to the language used by Nigel Farage, who wants a 'national security emergency' officially declared to stem the crisis.

Keir Starmer believes that migration is a law and order issue that can be solved with greater global co-operation. The PM wants to use every international forum available to champion cross-border collaboration and point the finger of blame solely at the criminal gangs. Morgan McSweeney, the No. 10 chief of staff, told Labour MPs last month to talk more about migration – or else risk losing their seats in 2029. With Reform making in-roads in longtime Labour heartlands, ministers hope today's speech shows Starmer takes voters concerns seriously.

The problem is that many of these measures announced today are exactly what the Conservatives were doing in government less than six months ago. More powers, further funds and talks with Italian leader Giorgia Meloni were exactly what Rishi Sunak was doing in No. 10 – plus they had the Rwanda scheme to work as a deterrent. Labour, of course, scrapped the scheme on day one in office, brandishing it a mere 'gimmick'. That word 'gimmick' is now being hurled back at ministers by Tories who feel as though Labour have learned little from the last four years. As an official party spokesman put it: 'Keir Starmer’s announcement on tackling gangs will mean absolutely nothing without a deterrent to stop migrants.'

Many within Labour approve of Starmer's refusal to blame the migrants themselves for making the hazardous journey to Britain. Privately, they feel much more comfortable bashing the criminal gangs and posing as the party of law and order. But this ignores the thorny question of incentives for migrants: cash, an expedited right to work, hotels and leniency against deportation. For all the promises of meetings and task forces, the danger is that until the incentives of Britain's asylum laws are addressed, the boats will keep coming – regardless of the risks.

Listen to Coffee House Shots, The Spectator’s daily politics podcast:

Is Kemi Badenoch the new Mrs Thatcher?

Prior to her election as Conservative Leader at the weekend, Kemi Badenoch was, on numerous occasions, compared to Margaret Thatcher. Simon Heffer, under the headline ‘No Tory has ever reminded me more of Mrs Thatcher than Mrs Badenoch,’ claimed that Kemi was ‘hard-minded, deeply principled, and has Mrs Thatcher’s vital grasp of what Rab Butler called “the art of the possible.”’ Tony Sewell spoke of her ‘Thatcher-like determination: “Because I believe this is right, I’m going to do it,” and said that today’s ‘biased and self-serving’ Civil Service was as much a dragon for her to slay as overweening Trade Union power had been for Mrs Thatcher in the eighties. Mark Dolan of GB News this weekend underlined the parallels, joking, ‘Thatcher was the Iron Lady, Kemi has balls of steel.’

The new leader has wisely distanced herself from such comparisons

The new leader, meanwhile, has wisely distanced herself from such comparisons: ‘I’m not Maggie. I’m not a chemist. I’m Kemi. I’m an engineer.’

Nevertheless, it’s interesting to look back through The Spectator‘s archive to see how the election of Thatcher was reported in 1975, and whether this has any light to shine on the present day. True, circumstances were different: Thatcher, far from being an obvious frontrunner, was thought little more than an also-ran when, after Ted Heath’s two election defeats in 1974, it was clear many in the Party were getting sick of their organ-playing, ocean-going leader.

Following the widespread industrial unrest, pay freezes and price controls of the banished Heath government, it was clear a completely new Conservatism was called for. Yet only after Tory grandee Edward du Cann ruled himself out of standing – for marital reasons – and Torch-Bearer of the Right Keith Joseph shot himself in the foot (with his notorious ‘human stock’ speech in Edgbaston, October ’74) did Thatcher put herself forward. ‘If you’re not going to stand, I will,’ she told the departing Joseph, ‘Because someone who represents our viewpoint has to stand.’ Her husband Denis was far from joyful: ‘You must be out of your mind,’ she recalled him saying. ‘You haven’t got a hope.’

Yet it was just this apparent hopelessness which campaign manager Airey Neave so cleverly, even deviously, exploited, to get her elected: ‘Jolt [Ted] by voting for Margaret,’ he told wavering supporters. ‘She won’t win, but she’ll give him a fright.’

Almost no one in the media supported Thatcher before the first ballot. Mrs Thatcher, the Economist said (speaking for many) was ‘precisely the sort of candidate who ought to be able to stand, and lose harmlessly.’ For Bernard Levin in the Times, it was Thatcher’s frostiness – worse, in his opinion, even than Heath’s – that made her unelectable: ‘There is no point in the party jumping out of the igloo and onto the glacier.’ Only The Spectator came out for Thatcher from the outset – in particular Patrick Cosgrave, its political editor.

Cosgrave was something of a character. Irish-born, thrice-married, a lapsed Catholic prone to the odd drink (and then some), a man constantly teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, he was nevertheless the canniest reader of political runes.

On 14 December 1974, two months before the leadership vote, Cosgrave wrote of Thatcher possessing a ‘quality of courage and endurance under fire’ that the Conservative Party so sorely needed ‘in its own struggle to win,’ and described her as ‘the foremost Tory in the country.’ Some of her faults Cosgrave was clear-eyed about: while recognising she had a ‘remarkably retentive memory, a quick logical intelligence, and the capacity to freeze a critic,’ she did sometimes respond with ‘an aggression that did not always serve her purpose; and she did not always seem to grasp that she was damaging herself thereby.’

But, for the moment, these were small objections. Mrs Thatcher had proved a highly competent Education Minister and Shadow Secretary of State for the Environment. She was also a brilliant performer in the Commons, quick with a comeback and regularly bloodying the nose of Labour Chancellor Denis Healey, a famous bruiser himself. On 1 February 1975, three days before the contest, a leading article in The Spectator argued that, having declared her candidacy some ten days before, she had ‘come to the fore as a challenger for the Conservative leadership’ and ‘emerged as a heavyweight candidate’ with ‘a distinct chance of winning.’

Mrs Thatcher, the piece went on, had ‘many of the attributes that the Conservative Party now most desperately needs in a leader…. She is a parliamentary debater of the utmost force, precision and wit.’ But ‘perhaps more important than any of these attributes, she has a definite understanding of the kind of Conservatism which the nation needs, and she would articulate it forcefully and with courage…’

‘What, then,’ the article ended, ‘are the Tories dithering about?’

They were not to dither much longer. On the first ballot she received 130 votes to Heath’s 119. On the second, following the ex-leader’s glowering departure, Mrs Thatcher, standing against colleagues like Jim Prior, Willie Whitelaw and Geoffrey Howe, received 52.9 per cent. The age of Thatcher – set to endure a decade and a half – had now begun.

Cosgrave was beside himself. In ‘Britain’s “second lady”’, an article published a few days later, he crowed that ‘the election of Mrs Margaret Thatcher as leader’ had given the party ‘after more than two years of ineffectiveness and decline, a new chance.’ It was Thatcher’s ‘directness, toughness and honesty’ which had won it, her ‘clear determination – and ability – to reclaim for the cause natural and hitherto loyal Conservative voters who have drifted away…’

Amidst the merriment and plain relief, a note of caution should be sounded

Despite the country’s most obvious problems – inflation, a high mortgage rate, seemingly incessant industrial strife – solutions would ‘come the better and the more readily from a leader who is obviously and sincerely a thinking and believing Conservative, who knows what has gone wrong, and who knows how to put it right. The party could hardly have chosen better: the quarrels of the recent past can now be put behind it, and a new future can begin.’

This upbeat note would be pleasant to end on, particularly as the outcome of last weekend’s leadership election was what so many of us hoped for, and for so long. But amidst the merriment and plain relief, a note of caution too should be sounded. Kemi Badenoch has asserted repeatedly of late that the Party must – before it even thinks of formulating policy – reestablish its core principles. Given that, it’s another article from Cosgrave, ‘Getting the Priorities Right’ (January 1975), which seems most pertinent:

‘It is the conviction that she stands for something recognisable as Conservatism which has gained so much support for her in recent weeks,’ he wrote of Mrs T. ‘Unless it is different, the Tory Party is nothing… But it cannot be too often said that, until the party decides where it wants to go, and what it stands for, it is unlikely to get any votes at all.’

Something for Kemi and her newly assembled Shadow Cabinet to ponder in the weeks and months ahead. The late, great Patrick Cosgrave, you can’t help feeling, would have raised a brimming glass to Mrs Badenoch, wishing her the best of Irish-British luck.

Watch more on SpectatorTV:

Do we care that the King is rich?

For the first time, the true extent of the property held by the King and the Prince of Wales’s private estates, the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall has been revealed, according to a splashy Sunday Times investigation. There are 5,410 separate properties up and down the country paying millions of pounds annually in rents and fees and charges. The NHS pays to warehouse its ambulances, the Navy pays for the use of jetties, charities rent London office blocks, and money rolls in for everything from the training of troops on Dartmoor to the housing of prisoners in a jail on His Maj’s land. ‘Revealed,’ the headline hoots, ‘The property empires that make Charles and William millions.’

Charities don’t get free stuff just by virtue of being charities

Is the discovery that the King is rich shocking? Probably not. Is the King’s making money out of that property shameful? Again, probably not. There’s an awful lot to disentangle, there. In the first place, we’re implicitly invited to disapprove of the sheer size of the landholdings that the King and Prince of Wales own – it being pointed out that a good deal of the 180,000 acres of land they own between them are ‘largely made up of land and seashores seized by kings in the centuries immediately after the Norman Conquest’. Jolly unfair, we may think. But that ship has sailed. There’s no plausible political or legal mechanism to expropriate all these royal goodies and return them to the descendants of whichever Angle-Saxon thegn they originally belonged to.

So, given that, like it or not, these are private properties owned by the King and Prince, it’s not unreasonable that they should rent them out. If they rent them, in some cases, to taxpayer-funded organisations such as the NHS or to charities, that might press the buttons emotionally but it’s not a sign of wickedness or rapacity. Are we to propose that in their private capacity, members of the royal family should be subject to different rules on commercial behaviour from the rest of us?

Charities don’t get free stuff just by virtue of being charities. Their chief executives, notoriously, don’t work for peanuts; and nor are they exempt from paying for stationery, computers, motor vehicles, the printing of leaflets, buildings or the rent for their offices. The taxpayer-funded NHS pays for stethoscopes from the companies that make stethoscopes, and where its hospitals and offices are on private land it pays rent for them. Sure, it might have been nice for the King to waive the £10,000 a year he gets to allow the Navy access to the oil depot at Devonport it uses to fuel – ahem – His Majesty’s warships. But the essential principle holds

Where the principle doesn’t hold, and should, is in two respects. At the root of this question, a distinction is made when it comes to property between the King as King, and the King as private citizen; a King’s Two Bodies issue, you could say, for the 21st century. On the one hand there’s the Crown Estate and the Sovereign Grant – which are properties held on behalf of the monarch qua monarch, and which fund the Royal family’s monarch-y stuff: upkeep of Buck House, provision of bagpipers for state occasions, replacement of red carpets, cleaning of ermine, lardering of posh scran to feed visiting foreign dignitaries etc.

On the other, there is the private wealth of the King and other members of the Royal Family. It is into this category that the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall fall. The more egalitarian among us may not like the vast extent of that private wealth, and we may even point out that the ancestors who accumulated it didn’t exactly do so on ordinary commercial terms. The ‘private’ wealth of the King is downstream from the royal privileges and military might of his ancestors. But that has never exactly been a secret, it’s not a revelation now, and there’s not much chance of changing it unless we fancy having another revolution.

But if it is to be regarded as private wealth, the same rules should apply to it as to private wealth held by any of the rest of us. In two respects, it doesn’t. The first is transparency: even when Parliament asked for a full list of the properties held by the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall in 2005, they were rebuffed. It has taken the Sunday Times’s investigative team months of painstaking work to build up a picture of the King and Prince’s holdings around the country. They have had to match property reference numbers to land titles, plot them on a digital map, and expend hours of shoe-leather reporting to obtain details of leases and contracts. If these properties are, indeed, held by the King and his son in such capacity as they have as private citizens, they should be right there on the Land Registry in the same way anyone else’s property is.

The second, and more important, anomaly is this: His Majesty and His Highness have struck a special deal with the Treasury for the Duchies which means they are exempt from both capital gains and corporation tax, and don’t have to comply with property laws such as compulsory purchase orders. I cannot for the life of me see why that should be, if it’s right that these are properties ultimately held privately by these men. You cannot simultaneously claim the rights of a private citizen and the privileges of a monarch. That is to attempt to ride, as has sometimes been said, two horses with one arse. Let it be private wealth, but let its owners be treated as private citizens before the law in every respect – not just the ones they like the sound of.

Southport suspect: A timeline of what was said and when

Three months after the Southport attack in July, suspect Axel Rudakubana has been charged with two new fresh offences. With his trial set to go ahead in January, there has been much comment in Westminster as to when the authorities were first informed.

To try and make sense of the case, Steerpike has laid out a timeline of events – from the day of the horrific attack up until the latest charges were announced.

Monday 29 July: Around noon, reports emerged that a knifeman had entered a Southport dance class and attacked the children present. Tragically three young girls are killed, with others injured before Merseyside Police detain the attacker. The Prime Minister writes on Twitter that he is appalled at the: ‘Horrendous and deeply shocking news emerging from Southport’ adding ‘I am being kept updated as the situation develops.’

Thursday 1 August: 17-year-old Axel Rudakubana is charged in connection with the attack. He appears at Liverpool Crown Court, facing three counts of murder and 10 of attempted murder following the killings. Following the Southport riots, Keir Starmer holds a press conference. He insists that ‘while there’s a prosecution that must not be prejudiced, for them to receive the justice that they deserve, the time for answering questions is not now’.

Merseyside Police release a statement saying ‘This incident is not currently being treated as terror-related and we are not looking for anyone else in connection with it.’

Saturday 3 August: The director of public prosecutions in England and Wales, Stephen Parkinson, said he was ‘willing’ to look at charging some rioters with terrorism offences – adding he was aware of ‘at least one instance where that is happening’.

Friday 25 October: Axel Rudakubana is due in Liverpool Crown Court for a pre-trial preparation hearing but his trial is not listed, with no official explanation given.

Tuesday 29 October: The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) announces that Rudakubana will be charged with two further offences after police found the biological toxin Ricin and a PDF document entitled ‘Military Studies in the Jihad Against the Tyrants: The al-Qaeda training manual’ at his address. In a statement the CPS says: ‘The two further offences relate to evidence obtained by Merseyside Police during searches of Axel Rudakubana’s home address, as part of the lengthy and complex investigation that followed the events of 29 July 2024.’

Serena Kennedy, the chief constable of Merseyside police, said the killings of the three girls were not being treated as a terrorist incident and that no evidence pointing to a terrorist motive had been discovered.

The Telegraph suggests that government law officers would have known about the new charges in the past few weeks as they would have had to consent to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) charging Rudakubana with the ricin offence under the Biological Weapons Act of 1974.

The CPS does not say when such evidence was obtained. A Downing Street spokesperson tells journalists: ‘We must let the police do their jobs and let the trial establish the facts.’

Wednesday 30 October: Axel Rudakubana appears at Westminster magistrates court via video link from HMP Belmarsh. He is next due to appear at Liverpool crown court on 13 November for a plea hearing on three counts of murder.

In Parliament, Lindsay Hoyle, the Speaker of the House of Commons, warns MPs ‘that nothing is said in this House which could potentially prejudice a proper trial or lead to it being abandoned.’

Thursday 31st October: Counter terrorism experts tell the Telegraph that police would have informed the Home Secretary of the discovery of a biological toxin like ricin ‘within hours’.

One suggests it would have been passed to the counter-terrorism police in the north west who would have informed Matt Jukes, head of UK counter-terrorism police, who would then have told the Home Office. In such a high-profile case, No. 10 may have been told.

Downing Street refuses to say if and when ministers such as the Home Secretary were informed about the discoveries of both the ricin and the PDF file.

Michael Caine turns on Labour’s taxes

Taxes, thousands of ‘em! In her bid to alienate the bulk of the British electorate, it seems that Rachel Reeves can add another to her enemies’ list: film legend Sir Michael Caine. The Zulu star – a true working-class talent made good – used an interview this weekend to send a warning about the Budget changes unveiled on Wednesday.

Caine, 91, famously left Britain in the late 1970s because of punitively high taxes under Jim Callaghan’s Labour government that peaked at 92 per cent. And he now warns about the same thing potentially happening again. Caine raised the spectre of multi-billion-pound tax rises being seen as a ‘punishment for success’, telling the Sunday Times:

Rich people can move their money about, and they do, especially nowadays. But if you’re just an ordinary person trying to work hard to help your family have a better life, higher taxes are going to clobber you. That’s when people say, “why should I bother to work harder if so much of what I earn is going to go straight to the taxman?

He said that in the 1970s Labour’s ‘super tax was really meant to be a punishment for success’, adding:

Nobody minds paying their fair share, but it can get to the point where you’re raising less money as a country because the tax rates are so high. I’m hoping this Labour lot don’t make that mistake.

Rachel Reeves is famously a student of Labour history. She’ll just be hoping it doesn’t repeat itself eh…

Kemi Badenoch isn’t the ‘black face’ of ‘white supremacy’

We need to talk about Dawn Butler. Following the election of the first ever black leader of a major party in this country, Ms Butler took to X not to congratulate but to sneer. Not to cheer this final breakthrough for racial equality in the UK but to share a poisonous description of the person who made the breakthrough as the ‘black face’ of ‘white supremacy’. It is one of the worst things a member of the ruling party has done since they came to power four months ago.

Labour’s Dawn Butler retweeted tips for ‘surviving a Kemi Badenoch victory’

Yes, when Kemi Badenoch was announced as the new leader of the Conservative Party, Labour’s Butler took potshots. She retweeted some tips for ‘surviving a Kemi Badenoch victory’ written by Nels Abbey, a London-based Nigerian journalist. He branded Badenoch ‘the most prominent member of white supremacy’s black collaborator class’. She’s the chief representative of ‘white supremacy in black face’, he sniped. And Butler pressed retweet, hand-delivering to her 240,000 followers this repugnant reduction of a black politician to a witless stooge of whiteness.

How dreadful is that? Badenoch has risen through the ranks of the Tories by gumption and drive. This weekend, she shattered the final racial ceiling by becoming the first black person to head a big party. Yet here she was being depicted as mere dressing, as an exotic decoration for ‘white supremacy’, as the black mask our supposedly racist elites have decided to pull on. This is dehumanising talk: it robs Badenoch of her agency, of her very individuality, and treats her as little more than the mouthpiece of a nefarious agenda that hurts her own kind.

Butler undid her retweet. We might be generous and think that perhaps she didn’t read all of Abbey’s words before sharing them. If that’s the case, she should say so. Because it is very serious indeed that a prominent figure in the Labour Party responded to Badenoch’s historic victory by sharing the foul view that this black woman’s chief role is to do the bidding of the white man.

Abbey and Butler were not alone in suggesting Kemi’s victory was a victory for ‘white supremacy’. The writer Kehinde Andrews, in typically provocative style, shared his view that Badenoch is the ‘shining ebony example that the Psychosis Of Whiteness is not reserved for those with white skin’. Oof. Everyone’s attacked in that tiny diatribe: both white people (we have psychosis, apparently) and black people (your ‘ebony’ shade doesn’t grant you immunity to our madness, it seems).

This cruel view of Kemi as ebony packaging for white supremacy exposes the left’s creepy disdain for black conservatives. Other Tories from ethnic-minority backgrounds have likewise been branded the fodder of whiteness. Priti Patel was labelled a ‘pawn in white supremacy’. She and the other non-white members of Boris Johnson’s first cabinet were written off as ‘ministers with brown skin wearing Tory masks’ (that was Kehinde Andrews again).

There’s an ugly racialism in this slamming of non-white Tories. The belief seems to be that these people are traitors to their race, that they’ve cheaply sold their black or brown souls for a seat at the white man’s table. Yet the idea that non-white folk should all think the same way politically – that they should all be dutifully leftish, pro-Labour, pro-immigration, anti-Israel – strikes me as obnoxious. It treats people from ethnic-minority backgrounds less as individuals capable of deciding for themselves what ideas to embrace, and more as a big blob that must uniformly conform to correct-think as defined by the cultural elites.

There’s an ugly racialism in this slamming of non-white Tories

Some on the left almost seem to think they have moral ownership over ethnic-minority people, hence their spitting fury when any of them ‘betrays their race’ and support the Tories. Imagine pushing an idea like that and having the gall to call other people racist.

It wasn’t only leftists who obsessed over Badenoch’s blackness this weekend, which they view as a mask for her ‘white’ beliefs. So did some on the very online right. Among those of an ethno-nationalist persuasion – of which there are more than you would like to think – the cry went up that an African is now in charge of the Conservative Party and that must mean it’s End Times. There were dark whispers of a ‘foreign’ takeover of the Tories. I’m not repeating it here – it was nasty stuff.

There is normally little to unite the crank left and the gutter right, two of the noisiest online tribes. But on Saturday they entered into a bizarre unholy alliance on the matter of Badenoch’s race. The former have a problem with her because she’s the ‘black face’ of ‘white supremacy’, the latter have a problem with her simply because she has a black face. Neither side seems capable of seeing her as an individual. As a free-thinking woman. As someone who should be judged for what she says and does, not her ‘ebony’ look.

These people are so out of touch. Most folk out there don’t care what colour Kemi is – they just want to know if she’ll offer an inspiring alternative to the disastrous Starmer government. It is only the identity-obsessed left and blood-and-soil right who look at Badenoch and see only a ‘black face’.

Watch more on SpectatorTV:

Why girls love fags

I can’t remember exactly when I had my first cigarette, but I remember roughly how I started. I was probably 13. I picked up one of my mum’s packets of ten Silk Cut, which was about half full. I slipped one out, put it in my pocket, saving it for later. My friends and I walked through the streets of Crouch End until we found a corner that was quiet and away from the prying eyes of our parents.

At funerals, everyone wants to smoke. People who gave up 20 years before and go jogging five times a week suddenly have a craving

We got our matches out, lit it, and passed it round. When the smoke first hit the back of my throat, I retched a bit and coughed but carried on. I got a head rush, felt dizzy, and within a couple of minutes it was gone. No, it wasn’t good for us. Those first times, it wasn’t even enjoyable. But we felt like we had entered a secret club.

After that, my secondary school friends and I often smoked. On our lunch breaks at school, we would go to one of the nearby shops and would buy illegal single cigarettes for 20 pence from under the counter. Then we would head to the park, often in the rain, and smoke. It made us feel older, more grown up, but it also brought us closer. We would sit in the park and gossip about life, flirt with boys, and moan about our parents, all in little clouds of smoke.

Later, I went to a trendy college that had a specially built smoking area in the playground by the sixth form block. It was still a couple of years before the indoor smoking ban came in. The smoking area was a dingy little thing – a pokey corner of the playground with two benches closely squashed together and a makeshift plastic roof. At lunch, the smoking area was heaving with us sixth formers. We would sit there, snuggled next to each other, sharing pashminas (the height of teenage sophistication at that time) and talk and smoke.

By then, I had moved on from my mum’s Silk Cut to my own Marlboro Lights. We talked about politics and the world. We hatched our plan to stage a big walkout in protest at the Iraq War. Me and my friend Hannah discussed the boys we thought we had fallen in love with – and the fact that they, sadly, had not fallen in love with us. And it was here that I first learnt about the intensity and joys of genuine female friendship. Girls I actually did love – and loved me back.

Technically, smoking had nothing to do with this. We had classes together. Those late teenage years are full of emotion and intense experiences for everyone. But for me, I learnt to navigate those years with a cigarette in one hand and my best friends’ in my other.

As I got older, my love of cigarettes ebbed and flowed. But there was one place where I always made sure I was stocked up with Marlboro Lights and plenty of lighters – when I went to my friend’s house in Suffolk. Her parents and siblings became a second family to me. They had lived near us in North London but moved when I was about 14. Both parents smokers. The mum smoked Café Crème cigarillos. Whenever I hear the sharp snap of the metal case Café Crèmes come in, I think of her. Her husband smoked full-on big cigars like a chimney. He always had one on the go and smelt, delightfully, of that rich tobacco cigar smell.

I looked after their children in the school holidays, and in return, they helped me grow up. They counselled me when I was struggling with my A Levels, gently prodded me to aim high when I was deciding which university to go to, and they were there to catch me when, after the Arcadian delights of Oxford, I struggled to work out what to do next. When the husband died suddenly, I felt like I had lost my own father. We were all distraught.

I rushed to Suffolk to help look after the kids while his wife, utterly heartbroken and shell-shocked, organised a funeral that came many years too soon. As I stood outside the little Suffolk church, I cried for my friend and mentor – and I lit a cigarette. At the wake, I was known as the girl with the cigarettes.

At funerals, everyone wants to smoke. People who gave up 20 years before and go jogging five times a week suddenly have a craving. The problem was, we were in a little seaside village and the only shop was closed. The people who ran it had come to the funeral. So I doled out my Marlboros to friends I knew – and plenty I didn’t – shared stories about him and grieved.

In my 20s and 30s, I fell in love with men. The early stages are the best; the stomach-churning thrill of meeting them, then the late-night chats – over too much wine and too many cigarettes. I listened to their secrets and told my own – invariably with a cigarette in my hand. When the outdoor smoking ban comes in, I’m sure I’ll smoke less. Who knows, maybe I’ll give up smoking altogether.

I’ll probably be a bit healthier thanks to cutting back. I might live a little longer. But I’ll miss making friends sitting in the rain in the smoking area, excitedly plotting the things we would do and the ways we would change the world. I’ll remember the tear-stained drags I took at the funeral of one of my greatest friends. And I’ll be sad that I can’t light up when gossiping and laughing with my mates in the pub. I think life will be a little plainer, and just a little sadder, with the prohibition.

What’s sadder than an ageing rocker?

‘Old soldiers…’ they used to say, ‘never die. They simply fade away.’ What a shame that the same can’t be said of old rock stars. The old codgers can’t be cajoled, shamed or otherwise persuaded to kindly leave the stages they have profitably adorned for half a century or more.

My lifelong rock hero, Jim Morrison of the Doors, had the good taste to die at 27

This unworthy thought came to me the other day as I watched 75-year-old Bruce Springsteen creakily strutting his stuff at a campaign rally for cackling Kamala. I have been a fan of the Boss since the 1970s when the perceptive critic Jon Landau dubbed him ‘the future of rock and roll’. But now that he has become the past of rock and roll, Brucie and his fellow rocker OAPs should hang up their guitars and sweaty jeans and prepare to the great recording studio in the sky.

Springsteen’s angst-ridden hymns seemed to suit the spirit of an anxious age – hymns to urban hard-scrabble American youth, racing their Chevvies in the summer streets, always menaced by unemployment, the mob, unwanted pregnancies and the decay of young lust into marital misery. But what is appropriate for a skinny young dude wondering from where his next meal or lay is coming looks absurd now that the Boss is a multi-millionaire long-married man, more worried about replacing hips and knees than getting girls to dance.