-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

It’s not so bad that JD Vance is ‘weird’

For almost a fortnight, the Democrats have had only one word in their word cloud when it comes to JD Vance: ‘Weird.’

On Sunday, Vance finally responded to the charge, on CNN’s State of the Union, calling it: ‘fundamentally school yard bully stuff.’ ‘No, we’re not ’, Trump had told a rally in Montana, a couple of days earlier. ‘We’re very solid people.’

Yet on it goes. From dawn to dusk, the CNBC/USA Today/NPR message machine has been pumping out the same word in the mouths of different commentators. This is no accident. The ‘weird’ meme is supposed to have started with Tim Walz, Kamala Harris’ VP pick, during an appearance on the TV breakfast show Morning Joe.

Never mind the disastrous overall failure of the Democrats, their capacity to get everyone pumping out the same line – be it ‘Biden is in the form of his life’ or ‘Vance is weird’ – has never been better.

In fact it’s too good: as with Theresa May in 2017, incanting ’strong and stable’ or Question Time audiences groaning as Keir Starmer winds up to the millionth ‘my dad was a toolmaker’, there is a point where even the most bovine voter wakes up to what is happening.

The recent repetition by Walz of an obviously false meme about how Vance ‘has sex with couches’ is the point at which ‘weird’ loses its attack value, and becomes a potential t-shirt slogan for the VP candidate himself.

It’s easy to see why the Dems felt it to be potent. The Kamala team’s strategy is evidently to polarise the election on a darkside/lightside axis. Kamala herself is clipped on the net running around being giddy with folksy normality. The vibe is that of the openings of Ellen Degeneres’s talk show, where Ellen would come out and dance for five minutes with the studio audience.

Meantime, Trump and the manboy goon he keeps in a basement are out there being ‘weird’. They want to set up a dichotomy between Dark America and Positive America. After all, ‘I just want everyone to get along, to be positive’ is the proto-political opinion of the core voter soccer moms and cat ladies the Democrats will need to turn out.

In one sense, Vance is about as normal as they come: difficult childhood in working-class America, lawyer, three kids, religious.

But the feeling Democrats are trying to set up is that there is something beyond that. In truth, Vance stands accused of two great American crimes: introspection and intellectualism.

America has often been characterised as an anti-intellectual nation.The intellectual is a bad pose for the US politician, because the politician’s job is to go out and grab hands. The politician, in this reading, must show that his hands are clean – that he is not hiding anything deeper than the persona he presents.

No one could accuse Joe Biden or Donald Trump of having rich inner lives. Obama perhaps. But not George Bush, or even the supremely intelligent Bill Clinton.

Vance is indeed a weirdo, because he seems to be interested in first principles, deep reading, and picking up ideas from unusual places. Much has been made of his interest in the Online Right, in the amateur political theorist Curtis Yarvin, or the many tendrils of the PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel.

To the likes of Kamala and her outriders, this is basically him sitting in his mom’s basement with 2l bottle of Pepsi and Final Fantasy VII: a card-carrying ‘incel’. They haven’t had the software update as to what the Online Right is now, and they have only a lo-res vision of their opponents’ psychology, and not much curiosity.

The Kamala meme is right in that Vance is intelligent enough to be interested in ideas

Had they bothered to engage fully with his intellectual biography, they’d find the Online Right is even weirder than their caricature. There’s an emphasis on wellness fads that seldom stack up – from raw milk to the sunning of the scrotum, to plenty of overly-deterministic evolutionary psychology. Many of the self-professed hard men who propagate these ideas are, in reality, a kind of analogue of the antifa types, in that both would be dead within five minutes of a real conflict breaking out. All parlour game, no street smarts.

The Kamala meme is right in that Vance is intelligent enough to be interested in ideas – and intelligent people often sometimes glom onto bad ideas. The salon debates of intellectuals created the French Revolution; ordinary people are not wrong to be suspicious of them.

But then, they also created the American Revolution. In those times, a self-starting weirdo crank like the pamphleteer Thomas Paine published his Common Sense anonymously – and struggled to find a publisher for a work aimed towards toppling the Empire. These days, he’d have an ironic anime avatar and 15k followers.

Labour poach Mirror political editor

Will the last lobby hack please turn out the lights? After Torcuil Crichton and Paul Waugh made the jump from journalism into politics by being elected last month, now another scribe has formally joined the Starmer army. After much Westminster speculation about the slowness of SpAd appointments, today Guido Fawkes revealed an interesting new hire. It transpires that the political editor of the famously partial Mirror tabloid has jumped ship – and right into the Cabinet Office.

John Stevens has opted to leave the world of lobby journalism for go and spin for top Keirleader Pat McFadden. During the Tory years, Stevens relished causing headaches for Tory spads with his scoops on ‘Partygate’ and the Afghanistan withdrawal. He replaced now-Guardian pol ed Pippa Crerar in 2022, after a five-year stint at the Daily Mail. His move today follows in the footsteps of another famous ex-Mirror journalist who left the lobby for Labour – though Mr S isn’t sure how many spinners would appreciate the Alistair Campbell comparison…

Still, who says the Labour party does nothing for the people of Cornwall?

Was it necessary to send this Facebook poster to prison?

Of the hundreds of people arrested in the wake of the riots, one in particular haunts my mind. It’s Julie Sweeney from Church Lawton in Cheshire. She’s a 53-year-old carer for her husband. And this week she was sentenced to 15 months in jail for writing an odious Facebook post while the riots were in full flow. Someone has to ask, and it might as well be me: who benefits from the imprisonment of this lady?

Many will be asking why certain forms of inciting speech seem to be punished more severely and more swiftly than others

Make no mistake: what she wrote was wicked. In response to a Facebook post featuring a photo of people helping to repair the mosque in Southport after it was damaged by riotous bigots, Sweeney said: ‘It’s absolutely ridiculous. Don’t protect the mosque. Blow the mosque up with the adults in it.’ What a vile sentiment. That she thought it is bad enough; that she wrote it down and pressed publish is insane.

She committed a criminal offence. Some of us would like to liberalise the laws around ‘harmful communications’, to ensure that speech that is merely offensive, unwise or alarming is not policed too severely by the state. But the fact is that in the UK in 2024 it is against the law to make a statement as reckless and inciting as ‘blow the mosque up’. It was inevitable that the cops would come knocking for Ms Sweeney.

But a long custodial sentence? Apologies for sounding like a bleeding-heart liberal, but is this necessary? Sweeney has been a carer for her husband since 2015. She has never troubled the law before. She has led a ‘quiet, sheltered life’. She accepts her post was ‘stupid’ and in fact she deleted it not long after posting it. She pleaded guilty to the charge of sending a threatening communication.

Could her sentence not have been suspended? Could she not have been sent home to her husband and her ‘quiet, sheltered’ life, with certain conditions imposed by the court? For instance, she could have been instructed to stay off social media. But 15 months in a cell? For someone who, by all accounts, had a moment of madness online during an explosion of street disorder? ‘Thank you, your honour’, she said, as the judge condemned her to jail. This feels more like a tragedy than justice.

Many will be asking why certain forms of inciting speech seem to be punished more severely and more swiftly than others. We’ve all seen gender crusaders say things like ‘Kill all Terfs’. ‘Decapitate Terfs’, said a banner at a pro-trans rally in Glasgow last year. A year on and Police Scotland insist the case is ‘still open’. Where was the uproar? It’s wrong to say violent-minded things about Muslims but okay to say them about women who believe in women’s rights? Two men have been charged with allegedly chanting about the massacre of Jews on the streets of London in 2021, and yet their trial has been delayed for years. No ‘swift justice’ there.

The post-riots climate is turning ugly. Yes, many of the rioters deserve stiff sentences, especially the weapon-wielding bigots who descended on mosques and hotels housing asylum seekers. But when I read about a 53-year-old carer being banged up for a gross post online, and a 13-year-old girl being convicted of violent disorder, and people getting jailtime for ‘dancing and gesticulating’ at a line of police officers, I can’t help but wonder if this is morphing into a judicial shaming of the lower orders.

Even more striking than the sentences themselves is the complete absence of concern from the activist class. Where are the civil-rights campaigners and left-wing voices who can usually be relied upon to ask ‘Is this a bit much?’ when tough sentences are handed down to certain communities? They asked that question after the 2011 riots. But now they’re schtum. Perhaps the ‘riff raff’ of Britain’s left-behind towns don’t tickle their sympathy bone as much as other sections of society do.

The riots were dreadful. No decent person denies that. Justice must be served. But the dearth of compassion in the aftermath of the riots is starting to feel a little unsettling, too. Here’s my plea for compassion: let Julie Sweeney go home. Wrecking a woman’s life and leaving her husband without care is too high a price to exact for a moment of bigoted lunacy online.

Former Irish PM defends Olympic boxer at centre of gender row

Well, well, well. Now Ireland’s former Taoiseach has swooped in to defend the Olympian at the centre of a gender row. Leo Varadkar’s gushing Instagram post in support of gold medallist Imane Khelif hit users’ feeds last night, accompanied by some rather odd graphics. The ex-Irish PM reposted a screenshot from the ‘@fitnessgayz’ account, with the words ‘Get em girl!!’ emblazoned across the image in bright pink. The former Fine Gael leader then launched into an impassioned defence of Khelif – who has faced backlash for competing in the women’s boxing after previously failing gender eligibility tests – and even suggested he would make a donation to her cyberbullying lawsuit against JK Rowling and Elon Musk.

‘Fair play to Imane Khelif,’ Varadkar declared on the photo-messaging app. ‘I hope she has financial support for her lawsuit. I’d be happy to make a donation.’ The ex-Taoiseach’s tirade continued:

She was born a girl, almost certainly assigned that gender by the doctor or midwife based on her physical characteristics. She was raised as a woman by her family and is accepted as such by her community. Even if she wanted to identify as a transman or intersex (which she doesn’t) that’s not an option for her in a conservative, religious, traditional country like Algeria. This is the world they want us all to live in and still they attacked her. Bunch of bullies looking for a soft target.

It hasn’t received the response Varadkar might have hoped for. One user fumed: ‘Do you have no regard for women’s safety and fairness in sport? Shame on you.’ Another reprimanded the former PM: ‘People don’t “identify” as “intersex”.’ A third commenter quizzed the politician: ‘Where is this energy coming from? Why weren’t you this excited when you ran the country?’ Ouch.

The ex-Taoiseach’s intervention follows the news that Khelif has filed a lawsuit over alleged cyberbullying during the Paris 2024 Olympics. After it emerged that the Algerian boxer had previously failed sex tests and was disqualified from last year’s World Championships by the International Boxing Association, there was uproar about Khelif’s participation in the women’s boxing. The fallout worsened after Italian boxer Angela Carini pulled out of her match against the Algerian just 46 seconds in. JK Rowling and Twitter CEO Musk were quick to take to Twitter to blast the International Olympic Committee’s decision to let Khelif compete – and the Algerian boxer’s attorney has suggested the duo are ‘named in the lawsuit, among others’. It seems the issue that clouded this year’s Olympics is very much not over yet. Stay tuned…

Britain’s growing GDP is good and bad news for Labour

The UK economy flatlined in June, as uncertainty over the general election and industrial action took their toll on economic growth. It wasn’t expected to be a strong month for the economy, with markets forecasting very little GDP growth, if any. But the small dip in services output – a fall of 0.1 per cent, driven primarily by a fall in retail trade – was disappointing after five months of consecutive growth.

Still, June’s figures are the perfect example of why one month of data rarely tells the full story. Businesses reported to the ONS that ‘customers were delaying placing orders until the outcome of the election was known’ which applied across manufacturing, construction, and services. Meanwhile the junior doctors strike held the weekend before polling day contributed to a 0.9 per cent hit in the human health and social work activities sub-sector, which also weighed down economic growth in June.

Meanwhile the broader story this morning paints a much more positive picture for the UK economy. While growth in June took a pause, growth in Q2 for this year is estimated to be 0.6 per cent, roughly in line with what markets were predicting, as forecasts for UK growth have been repeatedly revised upwards since the start of the year. Growth was 0.8 per cent in the three months to May, indicating the positive upward trend only paused at the start of the summer.

These numbers are reflected in the rather dramatic revision to the Bank of England’s growth forecasts for this year: an increase to 1.5 per cent, up from 0.5 per cent in their report from May. While the United States is reeling from far too optimistic growth forecasts at the start of the year, the UK is benefiting from lower expectations and better-than-expected results. Following on from the short and shallow recession experienced last year, Britain’s economic comeback is looking far stronger than even recently predicted, giving the UK a shot at a headline growth rate far higher than the 0.8 per cent predicted during the March Budget this year.

As noted before, decent growth figures are both good and bad news for Labour. It has not gone unnoticed – and it will not be forgotten – that Rishi Sunak and the Conservatives could have boasted about this economic good news if they had held off on holding the election until the autumn. This morning shadow chancellor Jeremy Hunt notes that the Q2 figures ‘are yet further proof that Labour have inherited a growing and resilient economy’ – one overseen by the Tories until the start of July. But Labour will get some of the credit now that it’s in charge.

But an economy on the up is not exactly the messaging Labour wants to push ahead of its first Budget in October. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s narrative – that the economy is a mess and the public finances ruined – is necessary to usher in the tax rises and possible spending cuts that we are expecting in a few months’ time. But better-than-expected growth – which is bound to give the Chancellor more fiscal headroom than Hunt had in March – is going to challenge this narrative, especially as Labour continue to use their first weeks in office to announce some major spending plans, mostly in the form of public sector pay hikes (the train driver boost this morning – a 15 per cent raise over three years – is the latest example).

The better the economy performs, and the more Labour spends in the run-up to the Budget, the harder it is going to get to fully pin any kind of ‘black hole’ solely on their predecessor.

Hear Kate's analysis on today's Coffee House Shots podcast:

Labour’s train driver capitulation is the first step to fiscal ruin

It has taken six weeks, but already the government has lost control of public finances. The decision to award train drivers a pay rise of 15 per cent spread over three years, and backdated, without any requirement to reform outdated working practices, won’t break the government’s piggy bank on its own, but is has set a course which, once again, will end with a Labour government leading the country to fiscal ruin – as every single Labour government has done before.

Public subsidy has corrupted the entire industry

Train drivers are already one of the highest-paid groups of workers in Britain, with basic salaries of £65,000 and with many earning over £100,000. This is not because they are being rewarded for huge commercial success. This is the backdrop to the long-running rail dispute: in 2022/23 the railways earned £9.2 billion from passenger revenue and a further £1.5 billion from other sources such as freight. Yet the railways cost £25.4 billion to run. The industry was saved from bankruptcy thanks only to £11.9 billion of government subsidy. That excludes, by the way, money spent on HS2 – it covers only current running costs.

The railways are already hopelessly unprofitable – and now Labour wants to make them even more so by forcing up rail operators’ pay bills, and without the possibility of any reform to improve productivity. True, it might be acceptable for public service to run at a loss if it is in the public interest, yet the government is treating train drivers as if they were working for some brilliantly successful industry and were simply demanding their fair share of the glittering profits. It is also true that train companies are themselves being allowed to walk off with fat profits in spite of making an underlying loss. Public subsidy has corrupted the entire industry.

A genuinely dynamic rail industry wouldn’t be racking up the wage bill for train drivers; it would be eliminating drivers altogether – with some higher-paid jobs available for those who were prepared to re-train for higher-skilled engineering roles. There are already over 100 metro systems around the world which operate entirely without drivers. The Victoria line was built 55 years ago with a minimal role for the ‘drivers’ – they only really open and close the doors. Britain once led on this technology, but has lost the initiative thanks to a craven attitude to rail unions.

It is not hard to see where this is going to lead. Now that the government has caved so easily to the train drivers’ demands, they will soon be back demanding more. Next year they will want 10 per cent. Other public sector unions, too, will take this settlement as a signal. What would you do as a nurse, currently paid half that of a train driver? You have seen the government grant above-inflation pay rises to junior doctors, teachers and others. You will want a slice of the cake, too. The government has set off what will very rapidly develop into a public sector pay spiral.

It is too early to guess who might be our next prime minister, but of one thing I am sure: that sooner or later we are going to end up electing a Javier Milei figure – the Argentinian President who posed at election rallies with a chainsaw, to symbolise what he was intending to do with public spending. Trouble is, Argentina went on for decades before it came round to accepting what was necessary to tackle the country’s rampant debts. It may take a while yet before we are forced to accept the inevitable: that we can no longer carry on living beyond our means. But Britain has certainly set off down the same path: the fact is that no UK government of any colour has succeeded in balancing the books in 22 years. On its form so far, the present government is definitely not going to be breaking that run.

Scottish Tory tore into ally’s campaign in WhatsApp statuses

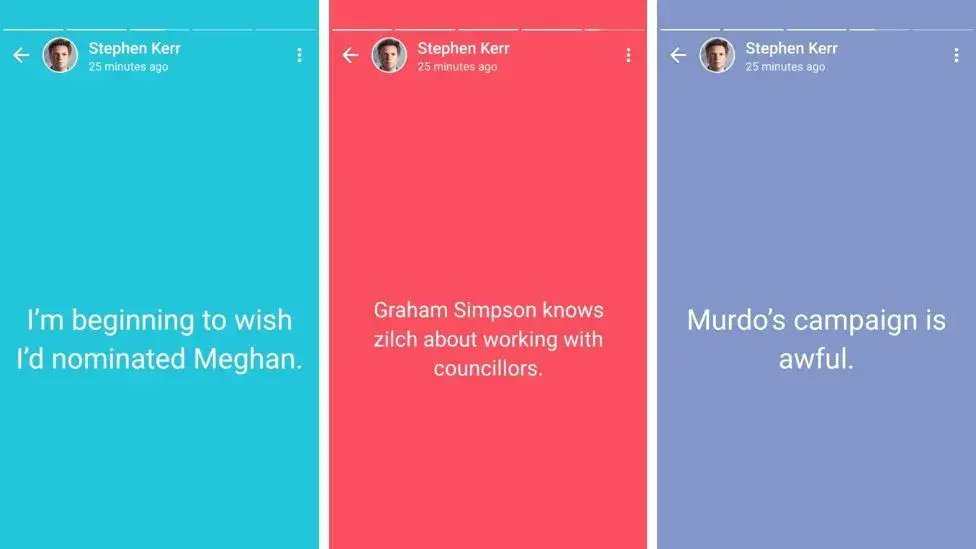

They say honesty is the best policy, but there are times when a little discretion is more advisable. It’s something Scottish Conservative MSP Stephen Kerr should note, after it emerged the politician had shared some rather candid thoughts about Murdo Fraser’s leadership campaign on WhatsApp. Not only are the messages damning – Kerr publicly endorsed the leadership contender last week – but it transpires that the MSP had been posting his criticism directly to his WhatsApp statuses, meaning that, er, all of his contacts could view them. Talk about analogue in a digital age…

In a series of posts, the former chief whip at Holyrood revealed his growing disillusionment with Fraser’s campaign – only a week after the nominations for Scottish Tory leadership candidates officially opened. Expressing frustration at the contender’s plans to run an event with another endorser, Graham Simpson MSP, Kerr fumed: ‘Graham Simpson knows zilch about working with councillors.’ In a twist of the knife, Kerr added: ‘I’m beginning to wish I’d nominated Meghan.’ And in another post he simply concluded: ‘Murdo’s campaign is awful.’ Don’t hold back, Stephen!

Fraser and Simpson both claimed they hadn’t seen the updates, and initially it seemed Kerr himself hadn’t quite cottoned on to how his messages had been discovered. He told the Times on Wednesday morning that it was ‘regrettable’ that ‘part of a private conversation is taken out of context’ publicly, adding: ‘The person with whom I was having the private conversation is a close friend.’ Perhaps not close enough to warn Kerr of his seriously questionable slip-up…

Liz Truss needs to learn to take a joke

It is hard to know what Liz Truss hoped to achieve by storming off stage during an event in Suffolk promoting her new memoir. The former PM did so after campaigners unfurled a banner emblazoned with the phrase: ‘I crashed the economy’ below a picture of a lettuce. All that Truss, who lasted just 49 days in office, succeeded in doing was to draw even more attention to the prank – the clip has amassed over six million views on social media. In the process she also managed to confirm what many have long suspected, which is that she really can’t take a joke, however lame.

Truss was sitting comfortably on stage, discussing the US presidential election, expressing her support for Donald Trump before she was pranked. ‘I support Trump and I want him to win,’ she said to applause from the audience. She added: ‘I think it was Bill Clinton’s adviser who said: “It’s the economy stupid”. So I think he [Trump] will, he probably will win. I’ve got a load of Trump questions, by the way.’

We just dropped in on Liz Truss’s pro-Trump speaking tour with a remote-controlled lettuce banner. She didn’t find it funny. 🥬 pic.twitter.com/jtSqaxycfF

— Led By Donkeys (@ByDonkeys) August 13, 2024

Pointing out her record – by telling tired lettuce jokes, among other things – is surely an example of the free expression that Truss claims to care so much for

She stopped speaking when her attention was drawn to the banner behind her. She was then heard to ask ‘what’s that?’, while the host responded: ‘I’ve no idea where that has come from.’ As she left the stage, some members of the audience laughed, while others clapped. Truss was heard complaining ‘that’s not funny’, before ripping off the microphone and walking away. She subsequently explained her actions on X:

‘Far-left activists disrupted the event, which then had to be stopped for security reasons. This is done to intimidate people and suppress free speech. I won’t stand for it.’

This seems rather far-fetched, to put it mildly. It was merely a banner lowered behind her: why not stay on stage and carry on? The only person suppressing free expression here is Truss with her absurd fit of pique. Predictably enough, Led By Donkeys, the campaign group behind the stunt, milked the Truss tantrum for all it was worth, trumpeting on X: ‘We just dropped in on Liz Truss’s pro-Trump speaking tour with a remote-controlled lettuce banner. She didn’t find it funny.’ This crowing is itself almost as pathetic as Truss’s silly over-reaction.

The lettuce image and joke has followed Truss around for some time. It gained traction in the final days of her brief spell in Downing Street, when the Daily Star newspaper launched a live stream of a lettuce to see whether Truss’s fight to stay as prime minister could last longer (for those who don’t know, the item in question was a 60p iceberg lettuce from Tesco). This stunt was in response to her mini-Budget, which included £45 billion of unfunded tax cuts, leading to economic and political turmoil. The former prime minister has previously criticised the lettuce joke, arguing in June: ‘I just think it’s puerile.’ She doth protest a little too much, me thinks. Truss, whether she likes it or not, prompted an economic crisis – her proposed reforms sent the currency tumbling and mortgage rates shot up – before a Conservative rebellion ousted her from office. She might now find it convenient to forget this period but that doesn’t mean others should follow suit. Pointing out her record – by telling tired lettuce jokes, among other things – is surely an example of the free expression that Truss claims to care so much for.

Our former PM, needless to say, sees things rather differently and is keen to look forward rather than back. Truss was in Suffolk trying to promote her memoir Ten Years to Save the West, in which she opines on the challenges facing democracies. It is part and parcel of her attempt to reinvent herself as a serious thinker and global strategist, which has led to her taking a growing interest in US politics. Last month, she had this to say to Republican supporters about her short stint in Number 10: ‘I’ve learned how powerful the unelected bureaucracy is. You have to win in November… you have to dismantle the leftist state… they are devious, they are ruthless and they are out to get you.’ This is more rewriting of history.

The only person out to get Truss was Truss, who managed to self-destruct in office in record time. She really should learn to see the funny side of these tragic events. Plenty of others do.

Are too many young people going to university?

University hopefuls trepidatiously opening their official A-level emails this morning will on the whole be happier than last year. All the indications are that they are more likely to get a college place, and indeed have a better chance of making their first choice. The reasons for this are complex, but largely boil down to two serendipitous facts. One is the disappearance of the artificial bubble created by Covid, which left universities overfilled and so constricted their scope for new admissions. The other is a drop in foreign applications, due among other things to students being discouraged from bringing their extended family with them, and to the collapse of the currency of Nigeria, from which many overseas students previously came.

The business model of reliance on an ever-increasing foreign intake to balance the books has its limits

All this will certainly please a good many UK teenagers. Is it good news for the country and for higher education?

In one sense it probably is. While the drop in foreign applicants, whose uncapped fees vastly exceed those paid by home-grown students, will give many universities a headache for the immediate future, it may in the long term raise quality. The business model of reliance on an ever-increasing foreign intake to balance the books has its limits. Some of the aura, and for that matter consumer attraction, of a UK education wears off when overseas students find themselves on a course geared to the fact that a large proportion of students are foreign and possibly without very good English. This is especially true if (as happens in a number of universities other than the one I teach in) corners are discreetly cut in the teaching and supervision of courses overwhelmingly patronised by overseas students to maximise the profit margin. Anything that serves to reverse these trends, even if in the end it may cost some government money, probably ought to be welcomed.

But in other ways, the news may be less good.

First, the apparently cheering facts that more applicants will get into their first choice of college than before, and that the lecture halls will remain full, come with a downside. Unless you buy the somewhat unconvincing line that UK school students have been getting remorselessly cleverer, more sophisticated and better educated every year, quality will go down and entry standards fall. This in turn will feed into more demands for remedial teaching and for already demoralised university teachers to spend yet more time instilling the basics into large and sometimes not very interested classes rather than encouraging students to think for themselves.

Secondly, the news that demand for places is now better balanced with their supply will encourage the idea Joanna Williams rightly took aim at in her book Consuming Higher Education: namely, that university, far from being something for which a limited number are suited, is just a rite-of-passage commodity to be distributed among, ideally, as many people as want it. The chief executive of Universities UK, Vivienne Stern, could not have put it better a couple of days ago: having referred to students taking ‘the course that they are passionate about,’ she then rather spoilt it by suggesting as an alternative a course that matched their strengths, or indeed one they had never thought of, which seems to translate as encouraging people to take university courses even if they don’t have any particular interest in them.

Thirdly, we have to fear that this morning’s results will encourage complacency about the way we do higher education.

There is a respectable position, hinted at by Rishi Sunak before the election, that the UK now has a tertiary education system too skewed towards universities. Put bluntly, this suggests that we have too many university students with skills people don’t need, too few apprentices and on-the-job trainees, and (whisper it quietly) possibly too many universities.

One interesting development this year was that, following the squeeze on admissions in the last few sessions, there was actually a rise in the number of those who might have been expected to apply to university but didn’t. This will be regarded by some as cause for worry: but there is a case for seeing it as an entirely wholesome development, born of a realisation that university study isn’t for everyone (and perhaps exposure to increasingly common anecdotal accounts of graduates who have saddled themselves with debts for courses they were pushed to do and now bitterly regret the whole exercise). It would be a pity if this year reversed this trend. We need some serious thought about how we approach higher education, in what ways the system is broken and what we should be doing to repair it. Business as usual may be nice for the higher education establishment: whether it’s good for the people of this country, or for UK Plc, is less clear.

The persecution of ‘the plebs’

Not so long ago we went to politicians for politics and comedians for comedy. Today, like many others, I watch politicians for amusement and listen to comedians for their political insights.

Whenever I want cheering up, I watch Kamala Harris riffing on a theme of her choice, or sometimes a Labour politician trying to explain why a woman can have a penis. By contrast Joe Rogan analyses political questions better than any of them, as does Noam Dworman, of New York’s Comedy Cellar.

So it was that when the question of free speech returned again recently, I did not turn to the hilarious Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood, but instead to the sombre and sage Rowan Atkinson.

It is ‘the plebs’ who have been marched to court sharpish during the speeding up of our justice system

Readers may recall that some years back both Labour and a Tory-Lib Dem coalition government tried to keep a law that made ‘insulting’ speech a criminal offence. The person who made the best case against this was Atkinson, who gave a speech in one of the committee rooms in parliament which showed a more astute sense of politics and principle than anything that had occurred in that place for years. While our present government tries desperately to crack down on social-media users, one part of Atkinson’s warnings is especially pertinent.

He noted: ‘I am personally highly unlikely to be arrested for whatever laws exist to contain free expression, because of the undoubtedly privileged position that is afforded to those of a high public profile. So, my concerns are less for myself and more for those more vulnerable because of their lower profile. Like the man arrested in Oxford for calling a police horse gay. Or the teenager arrested for calling the Church of Scientology a cult. Or the café owner [given a police caution] for displaying passages from the Bible on a TV screen.’

Recently I have been thinking of Atkinson’s wise words while following the cases brought against those who have been prosecuted for things they’ve said online. For instance, it is impossible not to notice that it is indeed ‘the plebs’ who have been marched to court sharpish during the unexpected speeding up of our justice system in the wake of this month’s riots. They include people like Bernadette Spofforth, a 55-year-old mother of three who, shortly after the Southport attack, rather got over her skis. Specifically she was one of those excitable people (and I will never understand why people do this) who wanted to name the suspect in the killings of the three little girls before anyone else did. She oongly repeated an internet rumour (though caveating it with ‘if this is true’) that the suspect was a man called Ali Al-Shakati who was on an MI6 watchlist and had arrived in the UK by boat last year.

Of course she was wrong, though the glee with which certain people celebrated those like her being wrong was something to behold. After all, there have been plenty of people with similar names on terror watchlists who have arrived here and carried out acts of terror soon afterwards. The Parsons Green, Reading and London Bridge attackers are a few examples. It’s just the Southport suspect wasn’t one of them.

In any case, Ms Spofforth is out on bail pending further inquiries. All this despite her acknowledging that her tweet was ‘a spur-of-the-moment, ridiculous thing to do’. Nevertheless, the same police forces that have not solved a burglary in half of the country for years are now policing unwise things people are saying online.

One oddity about this is, once again, the two-tier nature of the pursuit. People like Nick Lowles, from the incorrectly named far-left campaign group Hope Not Hate, also published fake information online. That particular dolt passed around a claim (swiftly shown to be false) that a Muslim woman in Middlesbrough had had acid thrown at her from a car window. The post was seen by more than 100,000 people and led to Muslim men appearing on the streets in the belief that they had to defend their areas from racist acid-attack monsters.

Yet so far as I know Mr Lowles has not had his collar felt, perhaps because he enjoys the government’s favour, as well as backing from prominent left-wing philanthropists such as Trevor Chinn. Kenan Malik of the Observer similarly passed around misleading reports in print and online this week, but also seems strangely immune from the law.

Lord Bingham famously said in 2006: ‘The law must be accessible and so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable.’ The government’s attempts to crack down on this month’s spontaneous and grass-roots riots is anything but intelligible, clear or predictable. Perhaps because (and this may be controversial, but it nevertheless seems true) there is no evidence the disorder was centrally organised. What appears to scare the authorities and much of the media is that the lawlessness was spontaneous and uncoordinated – something the ‘anti-fascists’ hoping to have street clashes with some British Nazi party appear rather disappointed about.

Meanwhile the uneven and unpredictable application of the law continues. Just last month, on arriving into office, Mahmood warned that UK prisons faced a ‘total collapse’ due to overcrowding, and that Britain risked ‘a total breakdown of civil law and order’, before announcing she would release thousands of inmates early.

Yet just weeks later, this threat of overcrowding seems to have magically disappeared. Indeed Mahmood appears intent on overseeing the locking up of any low–profile ‘pleb’ who has ever tweeted something incorrect or distasteful online.

I do not doubt that she, Keir Starmer and others will continue to give us all a laugh as they struggle at their jobs. But couldn’t someone arrange for Rowan Atkinson to become justice secretary?

The global fertility crisis is worse than you think

For anyone tempted to try to predict humanity’s future, Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb is a cautionary tale. Feeding on the then popular Malthusian belief that the world was doomed by high birth rates, Ehrlich predicted: ‘In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death.’ He came up with drastic solutions, including adding chemicals to drinking water to sterilise the population.

Ehrlich, like many others, got it wrong. What he needed to worry about was declining birth rates and population collapse. Nearly 60 years on, many predict the world will soon reproduce at less than the replacement rate.

But by my calculations, we’re already there. Largely unnoticed, last year was a landmark one in history. For the first time, humans aren’t producing enough babies to sustain the population. If you’re 55 or younger, you’re likely to witness something humans haven’t seen for 60,000 years, not during wars or pandemics: a sustained decrease in the world population.

A society’s reproduction level is measured by the fertility rate – the average number of children a woman has. The replacement level is accepted as 2.1: any higher and the population grows; any lower and it falls. Like the R number in epidemiology (which we heard so much about during the pandemic), the replacement level is a critical figure. Either side of it leads to dramatically different outcomes. The replacement level is put at a little over 2 to take account of the slight imbalance in male and female births – slightly more of the former are born. Also, not all girls survive until reproductive age.

According to the UN World Population Prospects, the global total fertility rate last year was 2.25 – a little above the replacement rate. But the UN was wrong. It’s not easy to calculate the figure because there’s a lack of statistics in many countries. In others, political constraints bind the organisation. For many places with reliable records, last year’s birth numbers were between 10 per cent and 20 per cent lower than UN estimates. In Colombia, the UN estimate was 705,000 births. Yet its national statistical agency counted 510,000.

For the first time, humans aren’t producing enough babies to sustain the population

There’s another reason to be sceptical of the UN figures – the replacement fertility level of 2.1 is valid for the UK, not universally. We get the 2.1 figure using a calculation: 1.06 boys are born for every girl in Britain. To ensure an average of one girl born, we need 2.06 children overall to be born. We then look at the probability a woman lives to reach her reproductive years, which in Britain is 0.98. To get the reproductive rate, we divide 2.06 by 0.98 – which equals 2.1.

However, in many developing countries fewer women survive to a reproductive age. Globally, the figure drops to 0.94. So the replacement fertility level needed worldwide is more than 2.1.

Many countries also have a higher male-to-female ratio, often due to selective abortion. In China, it’s around 1.15; in India, 1.1. An estimate for the sex ratio globally is 2.08. To estimate a global replacement fertility rate we divide 2.08 by 0.94, which comes out at 2.21 children per woman.

By adjusting the UN’s figures to account for the lower births in many countries, I estimate the global fertility rate last year was 2.18, i.e. below the 2.21 replacement threshold. It could be even lower than that, as it’s likely that the birth rate in many African countries saw a larger fall than the UN estimated.

This doesn’t mean the global population is already falling. ‘Demographic momentum’ means that women born in the 1990s and 2000s are currently having children, while their parents’ generations haven’t yet died. Longevity, meanwhile, is increasing. So although global births are falling, they still exceed deaths. At present rates the human population will peak in around 30 years. Then start plummeting.

Economists have long predicted fertility rates would decline as countries become wealthier. But the fall over the past decade has happened in rich, middle-income and poor countries. It has also been faster than anyone predicted.

South Korea is the most extreme case. The fertility rate last year was 0.72 – roughly one-third of the replacement rate. In 2015, it was 1.24. In less than a decade, South Korea has transitioned from very low fertility to astonishingly low. And there’s no sign of this decline slowing. The same trend can be seen across Asia (China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Thailand, the Philippines and Japan).

But it isn’t unique to Asia. Turkey’s fertility rate plummeted from 3.11 in 1990 to 1.51 in 2023. The UK’s was 1.83 in 1990, 1.49 in 2022. The situation in Latin America is striking too: Chile and Colombia had rates of 1.2 last year, Argentina and Brazil were at 1.44 – all well below the UK. Each of them had high fertility rates three decades ago.

A non-exhaustive list of countries where the rate isn’t only below replacement but falling quickly includes India, the US, Canada, Mexico, Bangladesh, Iran and all of Europe. We know less about Africa because of poor quality data. The available evidence, however, suggests it’s undergoing a rapid decline: where we do have more reliable information – Egypt, Tunisia and Kenya – it shows fertility rates plummeting at an unprecedented pace. The only countries where fertility isn’t falling are the former Soviet Central Asia republics, and they are too small to make much difference.

Whenever I raise the issue of falling birth rates during lectures, I’m always met with three questions. The first is: won’t a falling population benefit the environment? This is misguided. A gently falling population could be good for sustainability, but we’re facing population collapse and economic turmoil. Environmental concern is a ‘luxury good’: we do it more when prosperous. Voters in 2050 in a country with acute budgetary problems caused by an ageing population will care a lot less about global warming.

The second question is: can’t we bring in more immigrants? But the falling population is for the planet, not one country. Every Argentinian who moves to Spain alleviates Spain’s demographic woes but aggravates Argentina’s. This argument also ignores the huge number of immigrants needed to keep the population constant in countries such as South Korea. By 2080, 80 per cent of people living there would need to be immigrants or the children of immigrants. Can any society absorb so many without social unrest?

It’s not clear either that immigration fixes pensions or healthcare costs. When immigrants are young, they pay taxes; as they grow old, they draw pensions and use health services. The same is true for first- and second-generation immigrant children.

The third question is: won’t AI make a population collapse immaterial by doing all the work for us? This is wishful thinking. AI’s effect on productivity won’t match the hype. Daron Acemoglu, a leading expert on the macroeconomics of AI, estimates it will increase productivity by 0.66 per cent over the next decade. Even multiplying his estimate by ten, the figure would be much lower than what’s needed to overcome the declining labour force. The gulf between what the McKinseys of the world think and what the real experts think is vast.

Then there’s the fact that AI can’t deliver the services actually needed. It’s easier to teach a machine to read financial statements than to empty bedpans. The problems caused by population collapse, such as empty rural areas and unbalanced family networks, cannot be fixed by AI.

Countries from France to South Korea have introduced policies such as extended parental leaves and generous child tax credits. These have had limited success in reversing the decline. Raising a child is an 18-year commitment; extending parental leave from two to six months offers marginal relief. Ditto tax relief schemes.

Fertility rates have fallen faster in large metropolitan areas than in rural areas, probably because of housing costs. Take Bogota, Colombia. Last year its fertility rate was 0.9, far lower than in rural Colombia. The same is true in Mexico. In Mexico City, the fertility rate last year was 0.95, much lower than in rural Mexico. Both cities are very expensive. Extra-low fertility rates in South Korea are most likely driven more by the astronomical real-estate prices in Seoul than by any other variable. Small, expensive homes deter fertility.

Our societal structures have also become deeply unwelcoming to large families. Child car seats are a good example. In the UK, children must use a child car seat until they’re 12. There’s evidence this lowers birth rates as it makes it harder to fit more than two children in a car. When I was young my parents put four of us in the back seat. This isn’t to argue for repealing car-seat regulations, but it’s an instance of government policies having unintended consequences.

Another issue is that social norms have shifted: raising children isn’t a priority for many, not in the more conservative societies of East Asia or the more progressive ones of northern Europe. In 2016, China abandoned its one-child policy and allowed couples to have two children. The fertility rate increased from 1.57 in 2015 to 1.7 in 2016. By 2018, the effect had disappeared: it fell to 1.55 – lower than before the restriction was lifted.

If the UK government were to devise a strategy to increase the fertility rate from 1.49 to around 1.8 – still below the replacement rate but much closer to a sustainable level – it would need to address a mix of economic factors and societal support for large families.

Societal support could include making it easier for the young to marry. Safer streets would allow children to spend more time unsupervised and travel to school on their own, easing the burden on parents. School holidays could be organised in ways that don’t disrupt parents’ work.

Creating the conditions for large families to flourish is the only way to reverse the trend in fertility rates. If we fail to do so, then the coming demographic winter will be far harsher than anyone cares to admit.

Bankers are hot again

Lara Prendergast has narrated this article for you to listen to.

‘I’m looking for a man in finance/ Trust fund/ 6’5”/ Blue eyes.’ When Megan Boni posted this ditty on her TikTok account a few months ago, it was meant as a joke. She wanted to poke fun at the wish-list mentality of single women, herself included.

She couldn’t have predicted that her 19-second video would be viewed 26 million times and remixed into one of the summer’s viral hits. Women are now whispering to each other that maybe they really are looking for a man in finance, rather than an impoverished creative type still living with his parents at the age of 30.

‘Millennials felt ashamed about making money their focus. For Gen Z there’s no shame in flaunting wealth’

Boni has since reiterated that she’s ‘not actually looking for a man in finance’, and perhaps she needn’t bother given that she’s landed herself a record deal. But the damage is done. ‘Men in finance are hot again,’ says Vogue.

We all deserve a second chance, even bankers in their branded gilets. It will pain earnest millennials to hear this. Many of us came of age in the wake of the 2008 crash, when it was drummed into us that feckless City boys were to blame for the financial instability. We would hold ourselves to a higher standard, naively ‘following our dreams’ and prioritising a career that would add meaning, if not necessarily riches, to our lives.

The kids now think that’s daft. They may well have a point. It probably is a lot easier to chase your dreams when you’re not worried about rent. Who hasn’t read a millennial think-piece about how hard life is and thought: well, you made your bed.

For an accurate portrait of the modern finance bro, look to Industry, the hit HBO show. The third season began airing this week in the US and will soon return to the BBC. It gives us a glimpse into London’s gritty world of high finance, or what the New Yorker termed ‘Thatcherite brutality’. The overarching message is that no matter where you hail from, if you hustle enough, you might make it big. Or die trying. Or at the very least, shag the posh girl.

No wonder young chancers love what the show represents. The City is a place where a combination of skill and cunning can catapult you to the top. ‘This is the closest thing to a meritocracy there is,’ explains Harper, the twentysomething lead character, when we first meet her, ‘and I only ever want to be judged on the strength of my abilities.’ Never mind that we later discover she has lied on her CV to get a foot in the door and that she’s a bit of a crook. Hers is a very Gen-Z mindset.

The show was written by my friends Mickey Down and Konrad Kay, both of whom worked in banking before deciding to take their chances writing a TV drama about their experience. ‘The lustre really came off finance post-2008,’ Kon tells me. ‘Millennials felt ashamed about making money the focus of their career, while Gen Z, mostly thanks to smartphones, can monetise their identity. They get paid for being in the world and telling people how they live. There is no shame in flaunting your status and wealth.’

People don’t just walk into highly paid City jobs. It takes some planning if you want to end up gravitating around the Gherkin. This might explain why subjects such as maths and further maths are growing in popularity, with a record number of students taking A-level maths this year. Sure, governments will try to take credit for this shift away from more artistic subjects, but I’d be willing to bet a more compelling case for doing maths is that it might mean you earn loads of cash later down the line and get a girlfriend, even if you aren’t 6’5”. In the US, banking is now the top industry college graduates want to go into, up from fifth place in 2021.

I WhatsApp a twentysomething friend who skipped university but managed to wrangle a swinging-dick job in London. He has kept his eyes on the prize – money – and marches off to work each day in a smart blue suit. I think you can tell he doesn’t have a student loan to worry about.

Does he agree that his generation has different priorities to mine? ‘Lara, my friends and I are all openly obsessed with making money and changing our lives,’ he says. ‘We don’t care about doing noble professions, like you do.’ I send a laughing/crying face emoji back, which I know dates me.

He gives me a list of the groups and people he follows online for financial advice and tips. The groups are all called things like ‘Money Hustle’, ‘Get Rich’ and ‘Entrepreneurs Being Entrepreneurs’. One guy named Miles (or M.iles) is 25 and has almost half a million followers. His Instagram bio says that he is ‘probably wearing a @SIGNET® quarter zip’ and indeed he does seem to be in almost every photo, aside from when he is dressed in black tie or has his top off. He has blue eyes.

It’s tricky to tell if Miles’s account is a parody or not. There are photos of him cosplaying as Patrick Bateman. Either way, Miles is living the Industry life. He’s in a helicopter looking out at the Shard, then he’s off skiing with a bikini-clad ski bunny, popping bottles of champagne, before it’s on to a country wedding in a sports car, then back to Threadneedle Street and presumably the job that pays for all of this.

I can see why young men might want to be Miles. I can also see why Miles might not be a bad investment opportunity for women with certain… aspirations. ‘What’s better than selling out? Letting your partner sell out so you can afford to be a part-time artist and socialite, of course,’ says Vogue. If you’re looking for a man in finance, the queue’s over there.

Letters: Britain doesn’t have a ‘two-tier’ policing problem

Less is more

Sir: While I wholeheartedly agree with Toby Young’s observation that ‘more censorship would make things worse, not better’ (No sacred cows, 10 August), I’m confused by his remedy – ‘more and better speech’. First, how does one decide what better even means, without it becoming a form of censorship? Second, and perhaps more worryingly, it feels like something Stalin might appreciate. ‘Quantity has a quality of its own,’ he once said. In their different ways, both incessant social media and weekly magazines rather disprove that.

Grant Feller

Fowey, Cornwall

Backfiring rioters

Sir: The minority who threw bricks, set fire to vehicles and attacked police (‘Mob mentality’, 10 August) have now ensured that the rational and entirely legitimate concerns about mass immigration and illegal Channel crossings held by those who don’t throw bricks, set fire to vehicles or attack police will be further ignored.

Stefan Badham

Portsmouth

The state of reading

Sir: Mary Wakefield’s article struck a somewhat pessimistic note on the state of reading and the teaching of literature in schools (‘Book ends’, 10 August). I have worked as an English teacher in England and now Scotland for many years. I share the concern about screens, but let’s not be too despairing. The children I teach can and do produce imaginative and exciting creative work of their own. They always have and they always will.

Tess Killen

Balblair, Ross-shire

Screen off

Sir: In your poll ‘Who is your favourite character in children’s literature?’ (10 August), Toby Young says that he tried to interest his children in the books he loved as a child, but failed because they do not even understand what books are. I count myself lucky that I am not trying to pass on the joys of reading today, but had the chance to do so when it was a little easier a few years ago. My wife and I always thought that TV and computer games were the enemies of imagination, and so a grave danger to education in general. How can we understand the positions of those who disagree with us if we have little or no imagination? But in late 20th-century Oxford and in Moscow (where all the TV was in Russian) it was far easier to keep these things at a distance. Paradoxically, the main danger came from schools, where the social pressure to watch certain programmes or play computer games was strong.

Peter Hitchens

London

What, no Asterix?

Sir: I was surprised that the Asterix books did not feature in your poll of favourite children’s characters, and not just for their fun with Latin. Obelix – as a powerful champion of resistance, a hunter (of wild boar) and a devoted dog owner (of Dogmatix) – ticks many boxes. I loved his bewilderment at his foolishly militaristic adversaries. ‘Those Romans are crazy,’ he’d say, before he flattened a dozen of them.

Struan Macdonald

Hayes, Kent

A perfect anti-hero

Sir: I was surprised that none of your contributors nominated Billy Bunter. The Fat Owl of the Remove created by Frank Richards (real name Charles Hamilton, probably the most prolific author in the English language) is lazy, selfish, dishonest, no good at sports, the stupidest boy at Greyfriars, a frightful snob and addicted to jam tarts. This perfect anti-hero adorned my childhood and made me long for life at an English public school.

Francis Bown

London E3

Copy that

Sir: Anthony Horowitz is mistaken to say that Tintin ‘never actually wrote anything’. In his first adventure, Tintin writes a dauntingly long report from Soviet Russia. A raid by OGPU agents prevents him from filing, which surely is an excuse any editor would accept.

Deirdre Wyllie

Dull, Perth and Kinross

One-tier policing

Sir: I disagree with Rod Liddle’s assertion that the country has two-tier policing (‘Bring on the new football season’, 10 August). The tag reminds me of the endless fuss over racial disparity around stop and search. The day that officers are ordered to go easy on any group suspected of crime hasn’t arrived yet, and any chief officer who tried to order this would, I imagine, simply be ignored.

Richard Hill, Met police constable (retired) Hitchin, Herts

Bats need protection

Sir: We’d like to resolve Peter Krijgsman’s confusion about why bats are legally protected (‘Beware the bat police’, 3 August). It is true that ‘some UK bat populations have been stable or recovering since 1999’. But the UK’s 18 bat species all suffered severe historic declines before that baseline date. We monitor bat species, and are science-led when we say bats need protection. Out of the 11 mammals at risk of extinction in the UK, four are bats. We welcome the opportunity for a constructive dialogue to support the government’s aim of a ‘strong economy and environment this country needs and deserves’, but our natural heritage does not need to be sacrificed to achieve economic growth.

Kit Stoner

Chief executive, Bat Conservation Trust

London SW8

After the Olympics, France has to face its grim reality

The French television personality Laurent Baffie, interviewed by Le Figaro, came up with a nice phrase for the success beyond most expectations of the Paris Olympics: it had been ‘une parenthèse enchantée’, he said, but parentheses always have to close and ‘la merde va revenir’. I’m guessing he meant France’s brief political truce will end and attention will refocus on economic woes, even after a slight fall in unemployment – to 7.3 per cent, compared with the UK rate of 4.4 per cent – that was announced as another ‘bonne surprise’.

Writing from the Dordogne, where lunch is long and markets that matter are not global and financial but local and focused on tomatoes and melons, I hope you’ll forgive me if I take Baffie’s cue and offer a sunny interlude. La merde will hit the fan for sure in the autumn: in riot-scarred Britain, Trump-torn America and all across Europe as far as the Ukrainian front. But just for this week, I’m inclining to the brighter side.

Microcredit hero

One cause for optimism is the emergence of Muhammad Yunus as interim leader of Bangladesh after the ousting of the autocratic Sheikh Hasina. Yunus is a rare phenomenon: a Nobel laureate economist whose practical ideas have helped lift many thousands of people out of poverty. Another, though more controversial, is Hernando de Soto (once a presidential candidate in his own home country, Peru) who advocates awarding to squatters and street traders property rights that can be used to secure loans. Both men realised that access to credit – nowadays often seen as dangerous in the developed world – is essential for the most basic level of subsistence business-building.

Yunus’s epiphany was an encounter in 1976 with village women who were making bamboo furniture but had to borrow at exorbitant rates to buy raw materials. He lent them small sums of his own money on terms that allowed them to make a profit. They repaid him and he went on to institutionalise this system of ‘microcredit’ through the much-imitated Grameen Bank, which has since lent $38 billion to otherwise marginalised Bangladeshi borrowers, currently reaching 10.6 million of them. Hasina’s regime tried but failed to blacken Yunus’s reputation and now – at 84, three years older than Joe Biden – he’s been asked to grasp the reins of his turbulent nation. Let’s hope dark forces don’t rise against him.

Too cosy?

Here’s another good-news item – at least that’s how it was reported – emanating from the subcontinent: the arrival of the Indian telecoms titan Sunil Mittal as BT’s biggest shareholder, having bought the 24.5 per cent stake previously held by the French-Israeli dealmaker Patrick Drahi, who has problems elsewhere. An Anglophile with an honorary knighthood who also owns the Gleneagles hotel in Perthshire, Mittal has ruled out a takeover of BT and praised the chief executive Allison Kirkby for a ‘wonderful job’ rolling out full-fibre broadband to reach 25 million premises by 2026. All very cosy – but thousands of BT users waiting for stronger internet connections might dis-agree; and let’s not forget BT’s second biggest shareholder, Deutsche Telekom, whose boss said plainly last year ‘I want my money back’ after almost a decade of weakness in BT’s share price. A more threatening major shareholder might fire up BT’s performance on all fronts.

Summer ripple

But what about the pound? The financial market I can’t ignore, especially as a holidaymaker abroad, is the one in which sterling has posted its ‘longest run of losses in almost a year’ (Guardian) in reaction to street violence that made the UK a no-go destination for foreign tourists, the end of the short Starmer honeymoon and the first of what’s expected to be a series of interest-rate cuts. Is the thin hope of economic revival the Tories left behind about to be knocked out by a flight of foreign investors?

Nah, says my man on the foreign ex-change desk, who in quiet August trading has his feet up watching YouTube replays of the women’s beach volleyball final. In fact the pound has stayed in a range of $1.26-28 and €1.16-17, where it still is, for most of the year, with one brief April surge and dip fuelled by mismatched US and UK rate-cut signals. A fall of a little over 2 per cent from the high of the past month, also driven as much by US news as by events at home, is neither here nor there in terms of historic sterling volatility.

Remember when the pound in your pocket plunged close to dollar parity immediately after Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget in September 2022? That’s what a proper sterling crisis looks like. This, like the recent stock-market correction, is a summer ripple.

Sex, drugs and ripe tomatoes

Speaking of foreign exchange desks, something to look forward to in the autumn BBC schedules – or watch tonight if you have a teenager who can hack into the US HBO network, where it has just launched – is a third series of Industry, the drama that follows the dealings of young thrusters on and off the London trading floor of the fictional US investment bank Pierpoint & Co. Written by Mickey Down (ex-Rothschilds) and Konrad Kay (ex-Morgan Stanley), the show achieves a heightened authenticity worthy of Dickens in its financial detail, plus lashings of sex and drugs.

If your recently graduated offspring are contemplating careers in the money world, they may be fascinated or repelled by Industry, but they should certainly study past episodes to prepare for the job interview. Meanwhile, I don’t think it’s a spoiler to reveal that a suitably dramatised cover of The Spectator has a walk-on part in the new series.

And finally, back to the market that never disappoints – at Cazals in the Lot – to buy multicoloured ripe tomatoes for a delicious gazpacho. Another long lunch beckons.

Is it time for me to move back to Britain?

I first saw America 50 years ago. I spent the summer of 1974 with my New York girlfriend. Richard Nixon resigned halfway through my trip. Gerald Ford took over. My first visit spanned two administrations. It was a different country then. Income equality in America was better in the 1970s than it is in Norway today. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, it was better than anywhere in Scandinavia today. Politics was grubby, but retained a discernible spine. Congress was so appalled by the slush fund which paid the Watergate burglars that it passed tough election finance laws even before Nixon went. Those laws worked. Limits were imposed. Ten years later, Ronald Reagan won his 49-state re-election without holding a single fundraiser. The laws were toughened still further as late as 2002. Then they were smashed completely in 2010 with the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which held that the First Amendment prohibits the restriction of campaign expenditure. Thirty years of relentless bribery had paid off. Unlimited money was allowed. Talk radio and cable news delivered relentless propaganda. Now politics no longer exists in America. It has been replaced by a permanent kulturkampf so toxic, psychotic and deranged that it’s impossible to believe unless you live here and suffer it every day. The rest of the world thinks it’s bad here. They have no idea.

And now we approach the November election. Kamala Harris is a breath of fresh air, enthusiasm is high and polling looks good. If you could X-ray everyone’s brain on election morning, you would conclude that Harris would win big. But she won’t. The process has been corrupted by partisan placemen at state and county levels. Areas with Democratic tendencies have been robbed of polling stations. Twelve- to 14-hour queues are inevitable. Armed vigilantes will no doubt police those queues. Shadowy commissioners are empowered to certify the returns. Or not, as they alone see fit. Harris will need a huge margin to survive the erosion her votes will face. Even if she gets one, it won’t be over the next morning. There will be riots, gunfire and dozens of lawsuits heading speedily upward to the Trump-packed Supreme Court. It won’t be over by 6 January, or 20 January. There never was an ‘American Century’. The America of our popular imagination lasted just half that, from, say, 1930 until 1980, and it’s long gone now.

Obviously, being a novelist is the perfect work-from-home job. In the old days all I needed was a post office within driving distance; now, like everyone else, all I need is the internet. Writing tends to be a second-phase career, so novelists tend to be older, their kids grown up. Which means the home from which they work is probably just them and a partner. Maybe just them. No real ties to where the home is, except habit. Curiosity can be stronger. What would it be like to live somewhere else? First we tried a somewhat bohemian outer suburb of New York, then two years in France, then an apartment next to the Flatiron building, then a farm in Sussex, then a grand apartment on Central Park, then a ranch in Wyoming and a house in Colorado. The only constant was a New York City base, but even that is subject to curiosity. What would it be like to live in a brownstone townhouse? So I sold the Central Park apartment – eventually. I’ll tell the story, because dealing with it made me feel British again. The NYC Department of Buildings has a new database that reveals everything. Apparently 20 years ago someone remodelled my apartment and planned for a gas dryer in the laundry room. Then, still in the planning stage, they changed their mind to electric, and forgot all about the gas. But by then the gas permit had been obtained and, because they forgot all about it, had never been ‘closed out’ on completion of the work and showed up in the records as still active. I had to deal with it before I could sell. I arranged a city inspection, and I showed the guy that there was no gas connection. He agreed there wasn’t, but said the permit was so old it couldn’t be closed now. I would have to apply for a new permit. For something I didn’t want and wasn’t going to install? Yes, he said, and then have another inspection to prove it wasn’t there.

So if it all goes bad in November, maybe I’ll tie the above thoughts together. It’s easy for a novelist to move, and I’m too old and too tired to deal with the tsunami of crap that would be coming our way. What would it be like to live in Britain again?

In defence of strict teachers

Labour have become alarmed by the strict, ‘cruel’ approach to discipline in schools and the rise in the number of pupils being excluded. Teachers will need to be more relaxed about ‘bad behaviour’. But though moving the goalposts of acceptable behaviour may reduce the exclusion figures, it is bound to increase the burden of disruptive behaviour on teachers and other pupils.

My own experience of teaching tells me that the new guidelines will increase bullying and reduce special needs inclusion, undermine the most disadvantaged families and ultimately increase educational inequality. So why are they doing it?

The simplest explanation is just the return to dominance, in the post-Conservative era, of the ‘priest class’ of the progressive teaching establishment and their enthusiasm for ‘student-led’ classrooms. Tom Bennett, the education department’s current behaviour czar, has a low-tolerance, high-expectation approach. But he’s due to leave next year, and may be ousted sooner.

School should be the great leveller, a safety-net of authority with the same high expectations for every pupil, no matter what sort of background they have. Fortunate kids have parents who encourage them to behave and to succeed. Other kids have parents who don’t, which is why schools that do have high standards disproportionately help those who have been undermined by their backgrounds. The irony is that it’s most often the liberal, middle-class parents at the more privileged and stable end of the spectrum who complain about discipline in schools. They rail against ordered schools as if they were sadistic Victorian workhouses.

This is the ‘Matthew Effect’ in education, ‘To everyone who has, more will be given; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.’ The new Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson is herself a case in point. Having grown up in poverty in Tyne and Wear, she has described her luck at attending good state schools. But where she was truly lucky was that her family encouraged her and expected her to succeed. This is what it takes for a child to beat the odds of disadvantage.

The value of holding all children to the same standards is immense. Katharine Birbalsingh’s ‘strictest school in the country’ is also the most improved school in the country, and far outperforms other schools with comparative intakes.

It’s impossible to see how a more relaxed approach to discipline won’t be a disaster. A phone-free classroom is utterly essential for brain development, for instance, but children are now desperate to keep their phones. How can a ban on phones possibly work if a teacher can’t properly discipline those who disobey? Permitting ‘low-level’ rudeness towards teachers (talking back, shouting out, tutting) embeds disrespect for teachers into another generation of future parents, and this lack of respect will cast its own shadow across society for generations. To paraphrase Hannah Arendt, emancipating children from the authority of adults leaves them to the tyranny of bullies.

Awkwardly for progressives, it is well known that autistic children benefit from quiet in school, and one of the major reasons for neurodiversity-related exclusions is the increase of noise and chaos in the progressive ‘student-led’ classroom. This can send neurodiverse pupils into a downward punitive spiral.

There is widespread agreement that part of the problem in schools is truancy: the less time children are in school, the less they benefit from the structure it provides and the more they are at the mercy of the happenstances of home life. But allowing pupils to be rude will only make this worse.

The worst truancy in modern history was in fact enforced by the state. Schools were sporadically closed from March to September 2020, and then again from Christmas 2020 into spring of 2021, disrupting two academic years. Of course, this disproportionately affected the most disadvantaged families, further increasing the achievement gap. Teachers can see the effect of that catastrophic interruption as these whole-year cohorts rise through the system. The last children of the lockdowns are not due to leave school until 2033.

Too often in my school I see hands-off progressive teachers using teaching methods that are radically progressive and student-led alongside clumsily applied military discipline. The kids end up falling between two approaches in a worst-of-all-possible worlds.

How do Britons get their news?

SS-GB

The car company Jaguar said it won’t make any new cars for a year as it re-invents itself as an electric-only car company. For a long time the automatic choice of stockbrokers in the ‘gin and Jag belt’, the company had beginnings that were less luxurious. It was founded in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar Company to make sidecars for motorbikes. It produced its first car, a two-seat open tourer, in 1935, by which time the company was known as SS Cars. Remarkably, it retained this name almost entirely throughout the second world war until, to escape associations with the Nazis, it was renamed Jaguar – a brand name it had previously used on sidecars.

Info wars

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson wants children to be taught how to spot misinformation online. How do people in Britain get their news?

News websites – 47%

TV – 35%

Social media – 33%

Radio – 24%

Print – 15%

Source: Woburn Partners

Unsafe houses

Where in England are you most likely to lose your home?

Repossessions by mortgage lender (rate per 100,000 households)

Blackpool – 77

Newcastle upon Tyne – 60

Sunderland – 46

Evictions by private landlord were highest in:

Newham – 202

Enfield – 161

Dartford – 157

Evictions by social landlord were highest in:

Malvern Hills – 180

Harborough – 170

Bexley – 143

Source: Ministry of Justice

Under the hammer

A new record was set for a Bank of England auction, with a sheet of 40 connected £50 notes featuring King Charles III, which entered circulation in June, fetching £26,000; a £10 note with the serial number HB01 00002 was bought for £17,000. What are the most valuable items sold at auction?

– ‘Salvator Mundi’, Leonardo da Vinci: $450m

– ‘Les Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’)’, Pablo Picasso: $179m

– ‘Rabbit Sculpture’, Jeff Koons: $91m

– ‘Balloon Dog (Orange)’, Jeff Koons: $58m

– Qianlong Vase: £53m

Will Starmer make the Online Safety Act even worse?

Good God, there’s a lot of guff being talked about the Online Safety Act. This was a piece of legislation passed by the previous government to make the UK ‘the safest place in the world to go online’. To free speech advocates like me, that sounded ominous, given that ‘safety’ is always invoked by authoritarian regimes to clamp down on free speech. But after we raised the alarm, the government stripped out the most draconian clauses and put in some protections for freedom of expression, so even though it’s bad, it’s not quite as awful as it could have been.

What about the BBC, which got several things wrong in its reporting of an explosion in the car park of Gaza’s al-Ahli hospital?

Step forward Sir Keir Starmer. In the wake of the riots, the PM has dropped heavy hints that his government will toughen up the Act if social media companies, whom he blames for whipping up violence, don’t do more to remove supposedly harmful content from their platforms. But it’s unclear how he’d amend the Act or why his political comrades think it’s ‘not fit for purpose’ (Sadiq Khan).

Are the Act’s critics claiming the duties it imposes on companies to remove illegal content – stirring up racial hatred, for instance, or inciting people to commit crimes – are being ignored because the penalties aren’t severe enough? That would be an odd thing to argue since Ofcom, which has been given the job of enforcing the new rules, is still consulting about these duties and they won’t come into force until next year. When they do, failure to comply could result in a fine of up to 10 per cent of annual global turnover – which for Facebook would be more than £10 billion – and jail sentences for ‘senior managers’. Isn’t that draconian enough?

Or do they mean that one of the criminal offences created by the Act – the section 179 false communications offence, which came into force in January – applies only to disinformation, not misinformation? Last week, Cheshire police arrested a 55-year-old woman for wrongly identifying the Southport attacker as a Muslim asylum seeker, and kept her in custody for 36 hours before releasing her pending further investigation. I’m in touch with that woman, who’s a member of the Free Speech Union, and while she may be guilty of spreading misinformation, it would be hard to charge her with the ‘s179’ offence, because one of its tests is that ‘the message conveys information the person knows to be false’ and this wasn’t the case here. In her tweet, she added ‘if this is true’ and when she discovered it wasn’t, she deleted it. I’d be amazed if she’s charged, but if she is the Free Speech Union will pay for her defence.

Does Sir Keir want to broaden that offence to catch people guilty of spreading dangerous misinformation? If so, would that include the public health officials who, in 2021, overstated the efficacy of the Covid vaccines and downplayed the harms? What about the BBC, which got several things wrong in its reporting of an explosion in the car park of Gaza’s al-Ahli hospital on 17 October, overestimating the number of casualties and wrongly blaming an Israeli airstrike? No doubt that wasn’t deliberate – misinformation, not disinformation – but the report certainly caused harm, contributing to the cancellation of a peace summit between Joe Biden and various Arab leaders.