-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

The Israeli-Hamas negotiations are fraught with complexity

Jerusalem

For weeks the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had been preparing for an assault on Rafah. Yet when the order finally came on Monday night, it caught Israel’s generals by surprise. This was despite the fact that two armoured divisions had been deployed on Gaza’s southern border, and hundreds of thousands of leaflets printed warning the local population to evacuate to a ‘humanitarian area’ on the coast. Twice the plan to drop the leaflets over Rafah had been postponed, following American pressure. On Monday morning, when the green light came, the plan was to give civilians at least a week to move. Ten hours later the tanks moved in.

There was another reason for the generals’ surprise. A few hours earlier, a delegation of senior Hamas leaders in Cairo told the Egyptian government they accepted the proposal for a six-week truce during which Israeli hostages would be released. The generals believed that any major offensive would be on hold if there was a chance of a deal being struck.

The war cabinet had made two decisions: to send troops into Rafah and to send a negotiating team to Cairo to examine Hamas’s response. It looks like a contradiction – why launch an attack if there’s a chance of hostages being returned?

The generals in Cairo would love to see Hamas crushed by Israel but they are also fearful

There’s a strategic logic, however, behind Israel’s move. Hamas’s response includes major discrepancies with the original framework proposed by the Egyptians weeks ago, which Israel agreed to. Hamas has also been given discreet assurances that Israel will be pressured to continue the truce and accept a longer-term ceasefire. The chances of bridging these differences are slim: that’s why the Israeli delegation doesn’t include the chiefs of Shin Bet and Mossad who have a mandate to sign off on any deal.

On the other hand, the Israeli incursion is limited: the tanks didn’t go into the city of Rafah itself, where more than a million civilians are huddled, along with Hamas’s last full brigade of fighters. Instead, they captured a section of Gaza’s border with Egypt and the Rafah crossing. A tactical move that doesn’t cross the American- and Egypt-imposed ‘red-lines’.

There’s political logic too. Benjamin Netanyahu is under intense pressure from his far-right partners in government to launch an assault on Rafah. But the more pragmatic voices in the war cabinet, and much of the Israeli public, are urging a deal to secure the release of hostages. President Joe Biden has also threatened to slow down the supply of arms if the IDF enters Rafah. The limited incursion and low-level delegation to Cairo are an attempt to buy time. A classic Netanyahu move, and one that makes sense to all sides. But only for a short time.

By their very nature, hostage negotiations are complex affairs, conducted in deep secrecy. At least, that’s how these things are usually done. Not so the talks between Israel and Hamas. Like nearly all other aspects of this war, the most media-saturated conflict in history, every stage of the negotiations takes place under intense global scrutiny. Every day has to come with a headline, either of a breakthrough or of the talks being on the verge of collapse.

‘This isn’t how this kind of negotiation works,’ says one Israeli official who has been involved in previous talks with Hamas. ‘It’s a series of tiny movements back and forth where every detail is fought over. The media can’t capture these nuances. They need headlines.’ A series of leaks and briefings from all sides have provided these.

To make matters harder – and unlike in previous talks, where there was usually a professional go-between, often a veteran intelligence officer from Germany – the mediation is being carried out by three governments with their own set of interests. The Qatari regime, whose ideological and religious sympathies lie with Hamas, whose leaders it hosts in Doha and whose fighters it idolises, is also anxious to demonstrate to the West that it doesn’t support terror.

The military leadership of Egypt, meanwhile, harbours a deep hatred of Hamas, which shares an ideology with the Muslim Brotherhood. The generals in Cairo would love to see Hamas crushed by Israel. But they are also fearful of the situation getting out of hand in Gaza and thousands of Palestinian refugees pouring over the border into their territory. They also urgently want a ceasefire so that the Houthis in Yemen stop firing at container ships in the Red Sea, forcing them to take the longer route around Africa, and costing Egypt billions in lost revenue from the Suez Canal.

Then there are the Americans. Biden has strongly supported Israel since 7 October, incurring political damage at home in the process. But now he urgently wants a ceasefire so he can focus on a grand deal with the Saudis (which could include Israel as well) and turn his attention to fighting the election. Biden believes a truce and hostage deal could lead to a breakthrough with the Saudis. He’s heavily invested in the talks which are attended by CIA Chief Bill Burns.

To make matters worse, on the Israeli and Hamas sides, there are deep disagreements over the type of agreement that will be considered acceptable. Netanyahu suspects he is being manoeuvred into accepting a ceasefire under less than favourable terms. Israel may get its surviving hostages back but Hamas will also be allowed to survive. But he has only himself to blame: seven months into the war, he refuses to present his own vision for Gaza’s future. As the IDF wraps up operations in Gaza City and Khan Yunis, Hamas is re-establishing control there, with or without a deal.

Netanyahu’s fear of losing his far-right partners (which would lead to his government collapsing) and suspicion of any solution proposed by Israel’s allies has led him to squander the tactical gains of the IDF on the ground. Yet another bloody manoeuvre into Rafah may please his nationalist base but won’t solve that issue. Instead, he has manoeuvred himself into a position where a despairing America now threatens to slow down, even freeze, arms supplies, leaving Israel without their hostages and with a disastrously half-complete job in Gaza.

I hate hate speech laws

I originally intended to observe that American universities’ anti-Israel protestors and Hamas terrorists deserve each other, because they’ve so much in common. They’re both vicious, authoritarian, fanatical, powered by antipathy and focused on either unachievable or pointless aims (even if Columbia did divest from Israel, the pittance withdrawn would have no effect on financial markets, much less on Gaza). But many commentators have decried the protestors chanting ‘From the Mississippi to the Pacific!’ as poorly informed, faddish, spoilt, pathetic and anti-Semitic. So rather than assess the logic of what I’d have called ‘woke-lam’, we’ll pivot elsewhere.

On 1 May, the US House of Representatives passed the Antisemitism Awareness Bill by 320 to 91. After the chorus of ignorant, mindless and overtly anti-Judaic vituperation on American campuses, isn’t this bipartisan gesture of opposition to anti-Semitism refreshing? Well… no.

The Bill’s new definition of anti-Semitic speech is disturbingly broad. It includes: ‘targeting of the state of Israel’; ‘accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations’; ‘denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavour’; ‘applying double standards by requiring of [Israel] a behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation’; and ‘drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis’.

The most horrible places to live are those where you live in terror of letting slip some stray remark

To clarify: the US does not, and constitutionally cannot, permit laws against ‘hate speech’, which would violate the right to freedom of speech in the First Amendment. Should the Bill pass in the Senate, the above definition, which arguably extends to legitimate criticisms of the Israeli government, would be installed in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Department of Education. It wouldn’t criminalise voicing anti-Semitic sentiments per se. Yet in a rare instance of the otherwise irretrievably perverted non-profit doing its job, the American Civil Liberties Union has expressed concern that the Bill might pressure universities to restrict speech about Israel ‘out of fear of the college losing federal funding’. That’s not a negligible fear.

Indirect hate speech laws beat the direct kind. But across the West, the US is increasingly an outlier in its allowance of speech perceived to be unpleasant, and I’d like America to hold the line. For far more than any race, ethnicity, religion, sexual preference or nationality against which I might harbour some irrational prejudice, what I hate is hate speech laws.

Hatred is an emotion. It is not the business of the state to legislate how we feel or to make us into nice people by fiat. True freedom of expression entails the right to say things that others find disagreeable. I may believe fervently in the existence of Israel, but I believe just as fervently in the right of anyone else to say that they don’t believe in it or even that the country is racist. Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany are preposterous – hyperbolic, rhetorically impoverished and historically illiterate. But we should never stop the trite, the poorly educated and the feeble-minded from embarrassing themselves. By advertising their deficiencies, they do the rest of us a service.

Deeming a statement hateful is a supremely subjective exercise. Britain characterises as a hate crime anything the ostensible victim claims is a hate crime, which is legally absurd, relying as it does on no objective, statutorily specific standard. This eye-of-the-beholder definition is a formula for the pursuit of frivolous litigation and petty personal vendetta.

Hate speech laws are naturally expansive and grow only more prohibitive. Scotland has criminalised speech in your own home. Pending legislation in Canada would criminalise what you might say. In flagrant defiance of the bedrock democratic principle of equality under the law, the UK’s list of ‘protected characteristics’ grows ever longer. The population sheltered under the Equality Act’s clumsy umbrella could soon extend to all Britons who aren’t straight white men. Even the holding of certain opinions, such as belief in the reality of biological sex, is now ‘protected’. The answer isn’t to protect still more opinions, but to protect all opinions, including nasty or wrongheaded ones, and scrap the Act.

These laws easily slippery-slope to criminalising ideas. If you criticise the Islamic faith as predatory and intolerant, isn’t that anti-Muslim? It’s a commonplace for the media to conflate being anti-immigration with being anti-immigrant. By now, we’re all exhausted by the never-ending debate over whether being anti-Zionism or anti-Israel is unavoidably anti-Semitic. We can keep arguing, but it shouldn’t be up to the state to settle that dispute.

In outlawing crude statements of bigotry such as ‘I hate black people’ (curiously, you might get away with ‘I hate white people’), hate speech laws also imperil assertions with more nuance. How about, ‘The animosity and hypersensitivity of the BLM era has made me racist’ – which I’ve heard from more than one party. Should saying that be illegal?

In Britain, the prosecution of utterances, posters and tweets has distracted the police from pursuing actual criminals. But the blank page is the ultimate safe space. Words aren’t violence, any more than silence is. The US does sensibly disallow incitement to violence, which would apply to multiple anti-Israel protestors who’ve called for killing Jews. Short of that, expressions of bilious or vitriolic ideas can act as a safety valve. Better ugly speech than ugly acts.

I can’t think of a country that’s ever plunged into tyranny because it gave its citizens excessive latitude to say what they think, including the right to say mean things. Demagoguery and totalitarianism thrive on restriction and suppression of dissent. The most horrible places to live are those where you keep your mouth shut, you watch your back even in private and you live in terror of letting slip some stray remark that will destroy your livelihood and your reputation, perhaps even landing you in jail. Which sounds like just the sort of place that pending legislation in Ireland and Canada aims to manifest. It sounds like Scotland right now.

Tom Cruise and the art of falconry

Last week, the Hollywood team making the latest Mission Impossible film was desperate to clear Trafalgar Square of its superabundant pigeons for a scene involving its star, Tom Cruise. But it was not an ultrasonic laser in Ethan Hunt’s high-tech kitbag that did the trick. What you apparently need to rid central London of its pesky birds is an artform dating back 3,000 years.

The producers had to resort to falconers to get the job done. These devotees of an ancient art, who have also performed sterling service recently for administrators at St Paul’s Cathedral and the Palace of Westminster, let loose a ‘cast’ of red-tailed hawks, complete with bells and jesses, and sent the pigeons packing.

The Sun made a splash on these old-style methods, but actually it is one of falconry’s more modest contributions to the cultural life of the capital. Hunting with birds of prey arrived in Britain from Asia in about ad 900. Yet it took off with the Norman Conquest when every self-respecting wealthy Londoner had a ‘cadge’ (a technical hawking term for an enclosure) of falcons behind his residence in a building known as a ‘mews’.

These structures may have been repurposed as horse stables once falconry fell from fashion in the Georgian period. Yet everyone who lives in one of the many terraces of mews today dwells where London’s falcons would once have slept. Richard II’s own version was in Charing Cross, but the famous royal mews belonging to the fanatical falconer Charles II stood on a site now occupied by the National Gallery.

In keeping with strict feudal hierarchy, the various raptors used in falconry were allocated according to social station. Generally, the bigger the bird, the higher the status. Eagles were reserved for those of imperial rank, but a fierce giant of the Arctic tundra known as a gyrfalcon was a predator of choice for kings.

Highborn women had to make do with the tiny falcon known as the merlin, albeit a suitably bejewelled creature with its own brand of bijou elan. Catherine the Great and Mary Queen of Scots were both said to be much taken with their merlins. To the lowest in society, however, went the lowly mouse-catching kestrel. A dying echo of that feudal allocation is commemorated in the title to Barry Hines’s classic novel of thwarted working-class spirit, A Kestrel for a Knave.

For all the complex ritual that accreted around falconry, at its heart was a very practical business about delivering protein to the human diet. It was developments in firearm technology that eventually led guns to replace falcons as the hunter’s weapon of choice. Yet birds of prey supplied a genuine need for more than a millennium. Hawks were sometimes trained to work in pairs so that they could tackle far bigger prey items. Herons and cranes, which formed an exalted centrepiece on the medieval banquet table, were routinely captured with these methods.

Perhaps the most remarkable and deepest factor at play in a practice that held Europe in thrall for so long – and is still a multi-billion dollar enterprise among the royal families of the Middle East – is something much more elemental. It is a capacity to enter into a profound connection with a wild creature. Devotees often liken it to a marriage or a relationship between owner and slave, in which they are the servant. The bird itself is always master.

Do voters really prefer Starmer?

Rishi Sunak has been widely ridiculed for trying to spin the local election results as bad news for Keir Starmer. While acknowledging they were ‘bitterly disappointing’ for the Tories, the Prime Minister cited an analysis by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher, the renowned psephologists, showing that a similar showing by Labour in a general election would leave the party 32 seats short of an overall majority. ‘Keir Starmer propped up in Downing Street by the SNP, Liberal Democrats and the Greens would be a disaster for Britain,’ he said.

This was wishful thinking, according to John Curtice, the polling expert. He pointed out that the way people vote in local elections doesn’t mirror the way they’ll behave in a general. They’re more likely to vote for Lib Dems, Greens and independents in locals, he said, usually at the expense of Labour. The Tories, by contrast, didn’t lose many votes to Reform, because the party only contested one in six council seats. In those wards where Reform did stand, the Conservative vote fell by 19 points, an indication of what’s likely to happen in the general, where Reform has promised to fight every seat.

It’s worth remembering what a mountain Labour has to climb to win an overall majority

The bookies agree with Curtice and are currently offering 13/2 on ‘no overall majority’. Those odds are lengthening too – I got 13/5 when I put £50 on ‘no overall majority’ in December. But I still think that’s a decent bet because, like Sunak, I believe the chances of a hung parliament are underpriced. To be clear, I think the probability of Labour winning an overall majority is higher than 50 per cent – significantly higher. Just not as high as the pundits and the punters seem to think.

Take the by-election in Blackpool South, which was held on the same day as the locals. On the face of it, a big win for Labour, who overturned a majority of 3,690 to recapture the seat. But in fact the Labour candidate got fewer votes last week (10,825) than in 2019 (12,557). He won because the Conservative vote collapsed, going from 16,247 in 2019 to 3,218, not because of huge enthusiasm for Keir Starmer’s party. That’s of a piece with Labour’s national share of the vote in the locals, an anaemic 34 per cent, just nine points ahead of the Tories. Contrast that with Labour’s 43 per cent share in the last local elections before Tony Blair’s landslide in 1997.

It’s worth remembering what a mountain Labour has to climb to win an overall majority. So poor was the party’s result in 2019 that to secure a majority it would need a bigger swing than in 1997 – and Starmer is no Blair. When I’ve made this point to Labour supporters, they retort that Sunak is no John Major, who did at least manage to win an election in 1992. But such is the natural conservatism of the British electorate that the bar has always been higher for Labour. The party has had 19 leaders in its 118-year history – 21 if you count Margaret Beckett and Harriet Harman – and only three have managed to win overall majorities. Is Starmer in that league?

I suspect Labour won’t poll a significantly higher share of the vote at the next election than it did last week. One of the reasons the party lost support to Greens and independents is because the candidates fighting under those banners were pro-Palestinian Muslims. An analysis by the Telegraph found that in those wards with the highest proportion of Muslim voters – Blackburn, Bradford, Pendle, Oldham and Manchester – Labour support dropped by an average of 25 points. Those voters will only return to the fold if Starmer changes tack on the Israel-Hamas war and gives in to some of the demands made by the new ‘Muslim Vote’ group. But that risks losing support elsewhere.

The question, then, is how many people who voted Conservative in 2019 will either transfer their allegiance to another party or sit on their hands? It’s this combination of disillusionment and complacency that Starmer is counting on. But during the election campaign, the Tories will do their best to paint Starmer as a spineless ditherer who will be bullied by the trade unions, held hostage by the hard left and terrorised by Britain’s enemies. They might just frighten enough voters to rob him of victory.

There’s one final reason for thinking Labour may be heading for disappointment, which is that the British electorate has a habit of not giving overall majorities to leaders it still has reservations about. That was the fate of Harold Wilson in 1974, David Cameron in 2010 and Theresa May in 2017. Is it so fanciful to imagine Starmer joining their ranks? The message of the locals is the electorate prefers Starmer to Sunak, but not by much.

The Battle for Britain | 11 May 2024

How to solve ‘range anxiety’

In ‘The Adventure of Silver Blaze’, Sherlock Holmes mentions ‘the curious incident of the dog in the night-time’. ‘But the dog did nothing in the night-time,’ argues Inspector Gregory. ‘That was the curious incident,’ replies Holmes.

You never hear anyone say: ‘We finally stumbled across a charming little petrol station nestling among the trees’

Along with Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘Unknown unknowns’, this is perhaps the most famous example of what you might call ‘perceptual asymmetry’. We mostly act instinctively based on what is salient, giving little thought to what is easily overlooked.

It is hence surprisingly easy to change what people do simply by changing what they pay attention to. A magnificent example of this is the London Overground, one of the most cost-effective infrastructure projects ever undertaken, though the greater part of its success was achieved not with steel and concrete, but pixels and ink. Around 95 per cent of the track had existed for a century, but it was designated as a railway, not as a Tube line. Since most Londoners, in their solipsistic way, never consider surface rail as an option for short journeys, few had any conception that these lines or stations existed. By cannily pretending that these trains were part of the Tube network, and adding the routes to the Tube map, the invisible was made visible – and hence popular. The Overground now carries more passengers than the Elizabeth line, at about 3 per cent of the latter’s £20 billion construction cost.

I believe a similar issue – one of simple visibility – also applies to electric cars. As you are reading this, thousands of the world’s cleverest people are spending billions to increase the range of electric car batteries. The reason for this is to reduce a phenomenon called ‘range anxiety’. I suggest that it might be a lot cheaper to reduce anxiety than it is to increase range.

The truth is there is no such thing as range anxiety – we’ve all driven around in a petrol car with 30 miles left in the tank without suffering palpitations. It is really ‘infrastructure anxiety’. People know they’ll be able to find a petrol station to fill up within ten miles or so, but they don’t have the same faith in the availability of electric charging stations.

Actually Britain has a lot of electric charging stations. There are already more rapid and ultra rapid chargers than there are petrol stations. The problem is that you can’t see them. And there is an interesting reason for this. When petrol stations were first built, there was no GPS. Hence the way to sell petrol was to find a prominent space on a very busy road and set up shop with a big forecourt and a lot of bright lights in the hope that people would notice you and buy your petrol. Over time, through natural selection, the visible petrol stations survived, and the unnoticeable ones disappeared. Like peacocks, petrol stations have evolved to be ostentatious. You never hear anyone say: ‘We finally stumbled across a charming little petrol station nestling discreetly among the trees.’

By contrast, when electric car chargers were installed, the assumption was that everyone would find them using in-car navigation. There was no thought given to how prominent the locations were. Hence they are often found lurking unobtrusively in the far reaches of some obscure industrial estate. My local Sainsbury’s recently installed six 150kW chargers, but placed them in a remote exclave of the main car park. It was three months before I noticed they were there.

The solution is hence easy. Rather than increasing the range of cars, we just need to make car chargers much more flamboyant, so people realise how ubiquitous they are. They need bright flashing lights, laser displays, possibly an in-built barrel-organ. Immediately you’ll have people complaining that ‘these bloody car chargers are springing up everywhere’. To solve range anxiety, it isn’t cobalt and lithium we need – it’s neon.

Dear Mary: what should I do if a fellow passenger is reading porn?

Q. On a recent short-haul flight, I had the misfortune to be seated next to a much older man who read, for the entirety of the flight, an erotic novel on his Kindle. I tried to avert my eyes but the bright screen and lewd language kept catching my eye. I was stunned into silence for the 1.5 hours I was trapped next to him. Should I have said something, and if so, what?

– L.R.B., Bristol

A. Certain bridge players complain they can see others’ cards – and no doubt they can, but they don’t have to. Equally, lewd language on a next-door Kindle can only be seen with effort but you cannot be blamed for making that effort. Most book lovers would make the effort to assess the compatibility of an adjacent passenger. Sadly you were disappointed, and of course it would be disconcerting to be physically wedged next to such a person. Perhaps you might have disconcerted him by bringing out a pad and sketching a caricature of a fat naked man.

Q. A close friend – a single man – is giving a birthday party in Portugal in a few months. It would make all the difference if another close friend could travel out with me, but since the host doesn’t know her that well he hasn’t invited her. How can I ask him to invite her too without seeming pushy and/or self-interested? Or indeed, without embarrassing him if he doesn’t want to include her?

– Name and address withheld

A. Casually ask him if he would like any help with the guest list. For example: ‘Would you like me to give you a trigger list to remind you of people who you may not realise really like you or you may have forgotten about because you just don’t have them in your contacts?’

Q. Recently, at a wake in Chelsea, I spat a speck of sausage on to the jacket of the man I was chatting with as I was talking animatedly. I hoped he hadn’t noticed but, alas, after a few minutes I saw his hand wiping his jacket. Has this put him off me for life? We are bound to meet again as we have many friends in common. Also, should he have curbed his impulse to wipe off the speck and spare my embarrassment?

– E.S., Ripe, Sussex

A. Yes, he probably should, but there is nothing you can do about this not uncommon quandary. Comfort yourself that he has probably done some sausage-speck-spitting himself and the incident is unlikely to put him off you. On the same theme, in the event of someone spitting something directly on to your face, the correct protocol is to ‘accidentally’ drop something, then discreetly wipe your face while picking it up.

How to become an old soak

Drink and longevity: there seems to have been a successful counter-attack against the puritans, prohibitionists and other health faddists. Indeed, there is virtually a consensus that red wine has almost medicinal properties. That said, a confusion about so-called units remains. When the measurement was explained to me, I said that it sounded adequate. ‘Really?’ ‘Yes, that ought to be more or less enough.’ Then the cross-purposes were unscrambled. The 98 units or whatever – a figure clearly designed to give a bogus authority to the calculation – was a weekly total, not a daily one.

There’s no reason why

a normal wine-drinker should not live to be an old soak

There was a delightful medic called Patrick Trevor-Roper, the brother of the historian, but an altogether more amiable character. Patrick was a distinguished eye surgeon, spoken of with affection and respect by the many acolytes whom he trained. I once asked him about drink and health. His reply was reassuring. He said that unless one had an unlucky liver – ‘if that were true of you, Bruce, you’d know by now’– and as long as you took most of your refreshment in the form of wine, there should not be a difficulty. But if, like too many of my fellow Scots, you drank whisky in the quantities the French devote to wine, that would be a problem. There was, however, no reason why a normal wine-drinker should not live to be an old soak.

Another aspect of wine and long life occurred to me recently, after a couple of tastings. I have little confidence in my own ability to assess very young wines; nor am I a natural spitter. I once wrote of a yearling Latour that it was awesome and majestic, like a great mountain range dominating the sky, covered in cloud, but with the power shining through. I am sorry if that sounds pretentious, but Latour makes implacable demands on the language.

This time, I was tasting some 2023s, including Lafite. Although it did not have the raw strength of the Latour, this was clearly a great wine in the making. It had subtlety, length, depth and confidence. There was also a Duhart-Milon 2018 from the same stable. At first sip, I thought that it was the greater of the two. Not so, but it is a formidable wine. The obvious question is: when will these bottles be ready to drink? The experts were evasive. I would have thought ten years at the very minimum. Anybody born in 2023, with indulgent relations, would perhaps be able to look forward to the Lafite as the centrepiece of his 50th-birthday celebrations.

What about the aspirant old soak, cheered up by the Trevor-Roper dictum but with no realistic expectation of making a century? A few decades ago, a judge sentenced an 80-year-old villain to 14 years in prison. ‘My Lord,’ said the criminal; ‘I’ll never live to serve it.’ In reply, the judge almost sounded compassionate. ‘Well, you must serve as much as you can.’

For those of us still at liberty, it is a matter of extending life expectancy to keep pace with the cellar’s maturing. If I were rich enough, I would pile into the 2023s. For one thing, unless the world economy implodes, they will be an excellent investment. If all else fails, it is an investment which could be liquidated.

Well-seasoned drinkers and Château Lafite made me think of the late Jacob Rothschild, himself a man of great subtlety, length and depth: a paladin of old European high culture and a considerable oenophile. His London office was in Spencer House, just off St James’s Street, and he often used the Il Vicolo restaurant, much praised here, as a works canteen. He never booked a table, but merely sent one of his staff across with a bottle of Lafite: his own house wine. Gaudeamus igitur. Let us enjoy wine while we may.

Do sparks really fly?

‘Sparks,’ said my husband, after a short pause. I had asked him what one could spark. His answer was true but not all that helpful.

I had come across a headline on the BBC News website that said: ‘Record hot March sparks “unchartered territory” fears.’ The inverted commas around unchartered territory were not meant as so-called sneer-quotes, but to indicate quotation. Later the same day the headline was amended to uncharted and sparks was jettisoned.

There is such a word as unchartered. My distant relation by marriage, William Wordsworth, used it in his ‘Ode to Duty’, the one that begins: ‘Stern Daughter of the Voice of God!’ It is not among his fruitier numbers, I think. One of its couplets goes: ‘Give unto me, made lowly wise,/ The spirit of self-sacrifice.’ The poet asks for the aid of moral law, otherwise he finds, ‘Me this unchartered freedom tires;/ I feel the weight of chance-desires.’ It isn’t that he lacks a map or chart but that, like a chartered accountant, he wants a legal deed or charter ruling him.

You’ll remember that when Britain first, at heaven’s command, arose from out the azure main, this was the charter of the land. So Britain was never unchartered territory nor, implicitly, uncharted territory. If it were otherwise, fears might well be sparked. Fears are precisely the sort of things that are sparked. In providing the connotations of spark, as a verb, the Oxford English Dictionary suggests: ‘to be the immediate cause of (something hard to control)’.

Other verbal annoyances continue unabated. On Radio 4, I heard Scarlett Maguire, a political pollster, refer to a two-year anniversary (which I’d call a second anniversary). Humza Yousaf in his resignation speech said that the world watches on (instead of looks on or watches).

But I was delighted to hear the journalist Sonia Sodha say el-ECT-oral instead of the strange elect-OR-al (a weird twin of may-OR-al, which has also been much in evidence these days). I hope she has sparked a backlash.

Portrait of the week: Tory defections, local elections and a China defence hack

Home

The local elections proved dreadful for the Conservatives but not quite perfect for Labour. The Conservatives lost 474 of the council wards in contention, ending up with 515; Labour gained an extra 186 to reach 1,158. Independents and others, some standing on the issue of Gaza, increased their councillors by 93 to 228, and took away Labour votes. George Galloway’s Workers Party of Britain got four seats. Reform won only two seats but took votes from the Tories; it almost came second in Blackpool South, where there was a by-election which Labour won with 10,825 votes to the Tories’ 3,218. Ben Houchen (Lord Houchen of High Leven) won a third term as Mayor of the Tees Valley as a Conservative; Sadiq Khan for Labour convincingly won a third term as Mayor of London. Andy Street narrowly failed to be re-elected as the Conservative Mayor of the West Midlands, beaten by Labour’s Richard Parker by 225,590 to 224,082. Members of the Garrick Club voted to let women join.

John Swinney was elected leader of the Scottish National party after no one stood against him; the Scottish parliament then voted for his name to go to the King as its nominee for first minister. ‘The fact that I am the only candidate,’ he said, ‘demonstrates that the Scottish National party is coming back together again now.’ A man was found nailed to a fence in a car park in Bushmills, Co. Antrim, with a nail through each hand, in the early hours of Sunday morning.

China was blamed for the hacking of Ministry of Defence payroll information held by a contractor, with details of 270,000 service personnel. Another hacking group, Inc Ransom, released information taken from NHS Scotland. Train drivers belonging to the Aslef union went on strike. Freightliner, the railway goods train operator, said that private freight companies would not invest if plans by Labour and the Conservatives denied them access to routes. A burst pipe left 32,500 Southern Water customers in Hastings and St Leonards-on-Sea in East Sussex without water for days. Heineken is to reopen 62 of its 2,400 pubs (which numbered 2,700 in 2019). In the week up to 6 May, 1,375 migrants arrived in England in small boats. Electronic gates broke down at British airports. The Duke of Sussex visited Britain but did not see his father the King.

Abroad

Hamas said it had accepted terms for a ceasefire in Gaza. But Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel, said that the terms Hamas accepted were ‘far from meeting Israel’s demands’. Negotiations resumed. The Israel Defence Forces told 100,000 people in eastern Rafah to move to an expanded ‘humanitarian zone’. Israel carried out strikes on Rafah and said that it had taken control of the Gaza side of the Rafah crossing. President Joe Biden of America had phoned Mr Netanyahu and ‘reiterated’ Washington’s position that it could not support an invasion of Rafah without a plan to help the civilians sheltering there. At the Kerem Shalom crossing into Gaza, four Israeli soldiers had been killed in a Hamas rocket attack. Turkey suspended trade with Israel over its offensive in Gaza.

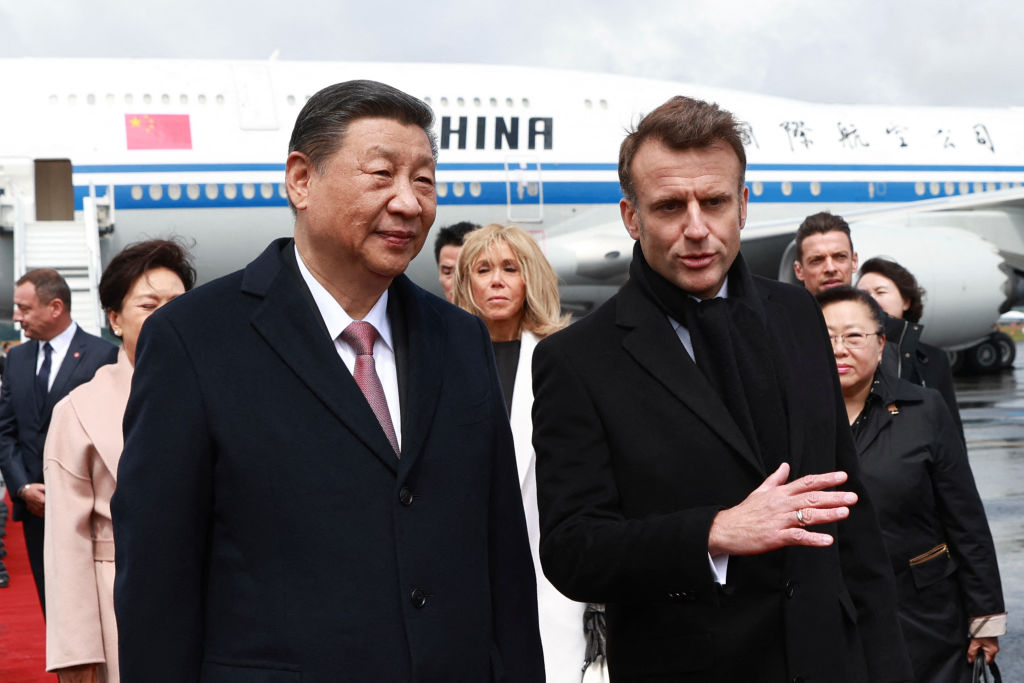

Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton, the British Foreign Secretary, met President Volodymr Zelensky of Ukraine in Kyiv, and said that Ukraine ‘absolutely has the right to strike back at Russia’. The Ukrainian security service said it had foiled a Russian plot to assassinate Mr Zelensky. Crowds in Tbilisi demonstrated against a ‘foreign agents’ law being put through parliament by the Georgian Dream party, which seeks closer ties with Russia and none with the European Union. Xi Jinping, the ruler of China, flew to France for his first visit to Europe in five years. Maersk, the Danish shipping group, said its ships were sailing faster around the Cape of Good Hope but were also using 40 per cent more fuel; it would not use the Red Sea route for the rest of the year.

America blamed the Rwandan army and the M23 rebel group for the bombing of a displacement camp in the Democratic Republic of Congo which killed at least nine people. An expanding economy and lower inflation in the United States were expected by the OECD and IMF to increase world trade. The judge in the trial of Donald Trump, after finding him in contempt for the tenth time, said that ‘future violations of its lawful orders will be punishable by incarceration’; the judge also cut short evidence by Stormy Daniels, a sex-film actress, about a sexual encounter she says they had. CSH

Bugs, biscuits, trench foot: from the front line of the uni protests

Angus Colwell has narrated this article for you to listen to.

On the grass in front of UCL’s main building, on Sunday night, there were about 30 tents and the portico was plastered in handwritten signs: ‘Students: You’re in debt so UCL can fund a genocide!’ Some protestors sat on chairs, eating biscuits. Others stood at the front gate chanting ‘From the River to the Sea’. ‘Do you want a tent, bro?’ asked one protestor. I explained that I was a reporter and was immediately whisked away to talk to a spokesman. ‘Spectator, Spectator … yeah, I think that’s left-wing. All good.’ A girl who had come along for the day received a keffiyeh tutorial and as night began to fall, I watched as most of the demonstrators headed towards the front lawn to pray.

One student didn’t fall asleep until 6.30 a.m. ‘Trench foot,’ he murmured

The next day, Oxford and Cambridge students joined in with their own protests. At Oxford, they got up at 4.15 a.m. and snuck on to the rainy grass in front of the Pitt Rivers Museum. By the afternoon, this was marshland and most of the tents were sliding into the squelchy ground. The Pitt Rivers is right next to a road, which meant trouble. A car drove past and a Cockney-sounding troll screamed: ‘Iz-ray-yawl! Iz-ray-yawl!’ Booing followed, and another round of ‘From the River to the Sea’. The tactic was to crank up the singing when the Sky News cameras started rolling, I was told.

At Cambridge on Tuesday, the vibe was more of a party. The sun shone on King’s Parade, and the protestors were singing. There was also some dancing: ‘Down, down with occupation, up, up with liberation!’ You bent down for occupation and got up for liberation, I learned.

During a break for lunch, some people rolled cigarettes, while others popped back to their college for a shower. An academic had brought a baby along, and they sat on the grass and had a picnic. Cambridge is full of very clever older people, and many of them stopped by to deliver their thoughts about decolonisation. A man asked a lady with a drum where she got it from. ‘Oh, I’ve had it since the “Kill the Bill” protests,’ she said.

The UCL demonstrators have three demands: for the university to ‘divest from companies that are complicit in the genocide, for it to condemn the war crimes that are going on, and for it to ‘pledge towards the reconstruction of Gaza’s education sector’. The Oxford protests have six, adding that they also want the uni to disclose all its finances, to boycott Israel and to stop banking with Barclays. At Cambridge, the home of analytic philosophy, they’ve taped an eight-page essay to the wall.

Some protestors have gone harder. ‘I hate that my tuition fees are funding a genocide, I hate that my tuition fees are funding BAE Systems and General Electric,’ said one student at UCL. ‘We want to get bigger and bigger,’ another girl added. ‘Peaceful protest? Rubbish, it does nothing. Zionist attitudes start young, and we need our institutions to correct that. None of us are free until all of us are free, until Zionism is gone.’ She pointed towards the university buildings: ‘We want to occupy their land! Spread, spread, spread!’

The UCL students told me they are establishing a permanent base: a select number of people who can always be there. Sleeping has been difficult. The other night was ‘rain, rain, rain’, one said. ‘There were tons of bugs, and I woke up and a massive spider was coming down.’ Another student shuddered at the memory. He didn’t fall asleep until 6.30 a.m. ‘Trench foot,’ he murmured.

There may be a festival vibe, but these encampments are ruthlessly organised. The protestors don’t normally believe in borders; they do here. They have dedicated media teams, and I learned that people are ‘onboarded’ when they join the encampment. Each site has a ‘programme’ plastered to the wall. At 9 p.m. at UCL, they watched a Palestinian film, projected on to the art school. When I arrived in Oxford, they were holding a plenary on the intersection between Palestinian liberation and disability awareness.

At Oxford, DPhil candidates were teaching their students in the encampment. One demonstrator, who is about to take her finals, looked at me with bloodshot eyes above her face mask. ‘I mean, the responsibilities I have here are meagre, compared to the responsibilities I feel towards Palestinian liberation.’

Food came from a mix of students, professors and older people who look at the protests and fondly recall 1968. At UCL, they have so much that someone takes the excess to a food bank at the end of the day.

British students didn’t seem too worried about getting rubber-bulleted and tear-gassed. One camper told me that UCL’s own security didn’t let the police in when they tried to enter on Friday. ‘They’re secretly pro-Palestinian, I can tell.’ The closest it came to kicking off was when, in one protestor’s words, ‘a Zionist’ went to the raised platform on the main building and unfurled an Israeli flag. He put it away and security ‘dealt with him’.

I asked a student at Oxford whether she thought that this made campus a hostile atmosphere for Jewish students. ‘Well, I’m Jewish,’ she said, adjusting her keffiyeh. ‘I don’t want to invalidate the experiences of those Jewish students, but this right here is where I feel safest.’

A Jewish student at UCL, who didn’t want to give their name, told me the past few days have been tough. ‘We were spat on by protestors who told us to go back to Poland. There was a woman chanting “Long live Hamas” and a speaker who said “Jews went to Palestine with a shovel in one hand and a sword in the other.”’ They said the protest has been endorsed by Cage, a group that Michael Gove said could qualify as ‘extremist’ under the government’s new definition. Non-student rabblerousers stood outside and some may have found a way in. ‘I wouldn’t have an issue if it were just UCL students inside the gates,’ a student said. When the encampment started, all pupils were told they would need ID to enter campus.

At the back of the UCL quad, I noticed two blokes in trainers stretching against the wall. They are studying maths and economics, and were off for a run. I asked them how they had found the encampment. ‘Well, I’ve had to move from where I normally sit in the library,’ one said. ‘But it’s fine. I can’t wait to just leave this all behind me.’

Inside No. 10’s battle of the pollsters

There was plenty for Rishi Sunak and his cabinet to discuss on Tuesday morning. The Conservatives had lost half of the seats they defended in the local elections and Andy Street narrowly lost the West Midlands mayoralty to Labour. ‘We’re doomed,’ was one cabinet member’s verdict. Ben Houchen’s victory in Teesside was just enough to stop any serious move against the Prime Minister: he is safe until the general election.

Isaac Levido, the Australian political strategist who ran the Tories’ successful 2019 campaign, did his best to fight off a sense of defeatism. He briefed the cabinet that this year’s election race is much closer than commentators and opinion polls suggest. Look at Dudley, he said. Keir Starmer had kicked off his campaign there saying he was ‘looking to win’. He used his final campaign visit to go to Harlow to make the same point. Yet Labour failed to take control of either council. Something was not going according to Labour’s plan.

Levido went on to argue that an election in which almost four million people voted offered a better sample than any focus group, than any opinion poll. And in that vote, there was not a 22-point Labour lead as some opinion polls had suggested. Instead, both the BBC and Sky had found the projected national vote share was a nine-point lead for Labour. Such a lead could easily narrow during a general election campaign. Michael Thrasher, the doyen of local election psephologists now used by Sky News, said that the evidence points to a hung parliament.

A member of government adds: ‘It’s so sad how much misery is priced-in now’

The BBC’s John Curtice had a bleaker reading of the same numbers. He said the results point to ‘a very comfortable Labour majority’, because local elections in England and Wales don’t take into account a Labour recovery in Scotland or other factors such as anti-Tory tactical voting in a general election.

Levido described Professor Curtice as a ‘political commentator’ compared with the ‘professional’ Professor Thrasher. He also shared some old predictions of political pundits – including a lobby hack who shared YouGov London mayoral polling ahead of the vote and confidently claimed that the polls would not narrow. In the end Susan Hall lost by 11 points, half the level claimed by YouGov.

The battle of the pollsters explains why some in Downing Street can find a silver lining. It’s not that they believe a hung parliament is the most probable outcome; it’s that there is at least the chance that things could be closer than the current Westminster consensus. The argument goes that if Labour were to do well in Scotland at the general election, they could still end up ruling with only a tiny, volatile majority. In the words of one CCHQ figure: ‘Good luck governing with that. It will be the people’s republic of Angela Rayner.’

The problem for No.10 is that this view is shared by very few outside the building. Most Tory MPs think they’re about to be bulldozed. One Tory MP – Natalie Elphicke – decided the results were so bad that she this week joined the list of Conservatives defecting to Labour. ‘It’s all very depressing,’ says a close ally of Sunak. ‘It shows we really are doing as badly as people think.’ A member of government adds: ‘It’s so sad how much misery is priced-in now.’ Anyone who does think Sunak will lead either a majority or minority government now can get 20:1 odds from the bookmakers.

The Tories are especially despondent about losing the Conservative stronghold of Rushmoor to Labour for the first time. ‘Rishi announced a boost to defence spending and then lost in the spiritual home of the British Army,’ says a senior Labour figure. ‘You couldn’t make it up.’ Sunak’s Tory critics such as Suella Braverman and Miriam Cates argue that the results show the party needs to move to the right to win back 2019 voters who are either staying at home or backing Reform. In response, Michael Gove invoked the spirit of Kate Moss at cabinet, warning against comfort eating on right-wing policies that make them feel good – ‘nothing tastes as good as skinny feels’.

Reform won only 15 per cent of the vote in the handful of places where the party stood. This was enough for several defeated Tories to blame Richard Tice’s party for their loss. But Sunak’s team argue that Tice made a misstep in saying he was ‘delighted’ to help Labour defeat Street in the West Midlands. The only other crumb of comfort for the Tories is that Reform came fourth in Ashfield, the seat of the former Conservative deputy chairman Lee Anderson who defected to Reform.

There are also calls for some personnel changes. There is plenty of ire towards the party chairman – Richard Holden – which tends to happen after a bad defeat. ‘He would start a fight with himself,’ says a member of government. ‘He turns off more people every time he does media.’

Starmer’s team is watching this aftermath with some amusement. While a few Labour aides have expressed surprise at the absence of a coup against Sunak, despite the fighting talk in the months before, they say it’s still a good result. ‘Tory psychodrama is clearly good for us but this result suits us just fine,’ says one party figure. ‘Rishi stays but with an awful set of results – and we know how to attack him. He helps us.’

As for Labour’s successes, beating Andy Street in the West Midlands is seen as a symbolic victory but not the most significant. Instead, the results celebrated most by Labour’s data team were the wins in the East Midlands and North Yorkshire mayoralties. ‘It’s prime Tory territory and it shows we are making the right inroads,’ says a Starmer aide.

Both the Tories and Labour have found their own narrative of how the local elections – the last significant encounter with the electorate before the general – offer hope. But it’s Labour that for now has the most to point to. The one thing the two sides can agree on is that after these results, Sunak is probably going to play for time and hold out for an autumn election. ‘It’s going to be a long six months,’ says one minister.

What Xi wants in Europe

Cindy Yu has narrated this article for you to listen to.

On a quiet street in Belgrade, a bronze statue of Confucius stands in front of a perforated white block, the new Chinese Cultural Centre. This is on the former site of the Chinese embassy which in 1999 was bombed by US-led Nato forces during the Kosovo war. Three Chinese nationals were killed. The Americans said the bombing was an accident, but the deaths allowed China and Serbia to share a common anti-Nato grievance. This week, timed to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the bombing, Xi Jinping visited Belgrade and talked about the Sino-Serbian ‘bond forged with the blood of our compatriots’. He had been expected to visit the embassy site but seems to have decided that that would be too provocative against Washington.

Xi has been on a week-long European tour and the countries he visited – France, Serbia and Hungary – could be viewed as some of the most Sino–sympathetic on the continent. Beijing’s relationship with France has become increasingly complicated as Chinese electric cars and solar panels compete with French manufacturers. Xi’s mission in Serbia and Hungary was more straight-forward: these have been two of China’s biggest cheerleaders in recent years.

China has spent more than a decade trying to woo Europe, beginning in 2012 when it set up an initiative called the ‘Cooperation Between China and Central and Eastern European Countries’, also known as ‘16+1’ (a reference to the number of European countries that joined). The tactic was straight out of the Belt and Road playbook: charming less wealthy nations with cash and investment while appealing to a narrative of historical solidarity wherever possible. The aim is to peel central and eastern European countries away from the US-led world order and weaken claims of ‘western unity’. Various EU members such as Latvia, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia were open to finding out what Beijing was offering. Five years ago, Greece joined, making it 17+1.

China had overpromised and by 2021 its partners had begun to back away. Lithuania was the first to leave, its foreign minister saying that belonging to the initiative had brought ‘almost no benefits’. Estonia and Latvia followed. They had good reason to be unimpressed: by 2020, most of the original 16 countries had seen very little Chinese investment. The region’s trade deficit with China had, in fact, been going up, not down.

The pandemic further tarred Beijing’s reputation. The final straw, especially for the post-Soviet states, has been China’s unwillingness to condemn Vladimir Putin after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Poland and the Czech Republic have become some of China’s fiercest critics in Europe.

As Beijing loses support in the rest of Europe, those countries that remain loyal are lavishly rewarded

Unusually, Serbs came to view China in a more positive light during the pandemic, thanks to some PPE and vaccine diplomacy. Aleksandar Vucic, Serbia’s President, called the Chinese his ‘brothers’ and lambasted ‘the fairy tale’ of European solidarity after the Commission limited exports of PPE to non-EU countries. When a million doses of the Sinopharm vaccines arrived in Serbia, Vucic kissed the Chinese flag on camera.

Similarly, when the Hungarian foreign minister, Peter Szijjarto, visited Tianjin last year, he called the European plan to ‘de-risk’ from Chinese supply chains ‘brutal suicide’. It was more the sort of language you’d expect to hear from the Chinese foreign ministry. Hungary has also consistently used its EU membership to block anti-China policies. In 2016, it watered down a statement condemning Chinese actions in the South China Sea. In 2021, it vetoed another one criticising the National Security Law in Hong Kong.

Covid, Ukraine, Chinese sanctions on European politicians and the influx of cheap Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels have all contributed to worse relations with Brussels. Under Ursula von der Leyen, the Commission has put in place new trade measures to investigate and punish Chinese offloading in high-tech industries. In the UK, news broke on Monday that Chinese hackers are thought to have targeted the Ministry of Defence, accessing the payroll data for most of the British Armed Forces.

As Beijing loses support in the rest of Europe, those countries that remain loyal are lavishly rewarded. China is the single biggest investor in both Hungary and Serbia. This week, Xi and Orban are expected to announce a new EV production plant in Hungary. This will come after a Fujian-based battery maker committed $7 billion to building a new factory in the largest ever single tranche of inward investment in Hungary. It is expected to create 9,000 jobs. In Serbia, work began this year on a new China-backed stadium and a renewable energy deal worth €2 billion.

How long can Budapest and Belgrade hold out against the European mainstream? There are signs that anti-China sentiment is on the rise in both countries. Polls suggest that Hungarian opposition MPs, media and the population in general see China more negatively than positively. In Serbia, activists are speaking out about Chinese contractors’ poor labour practices and environmental record.

China has seen that the tide of political opinion can change quickly. All it can do is keep doling out cash incentives and playing up victimhood narratives.

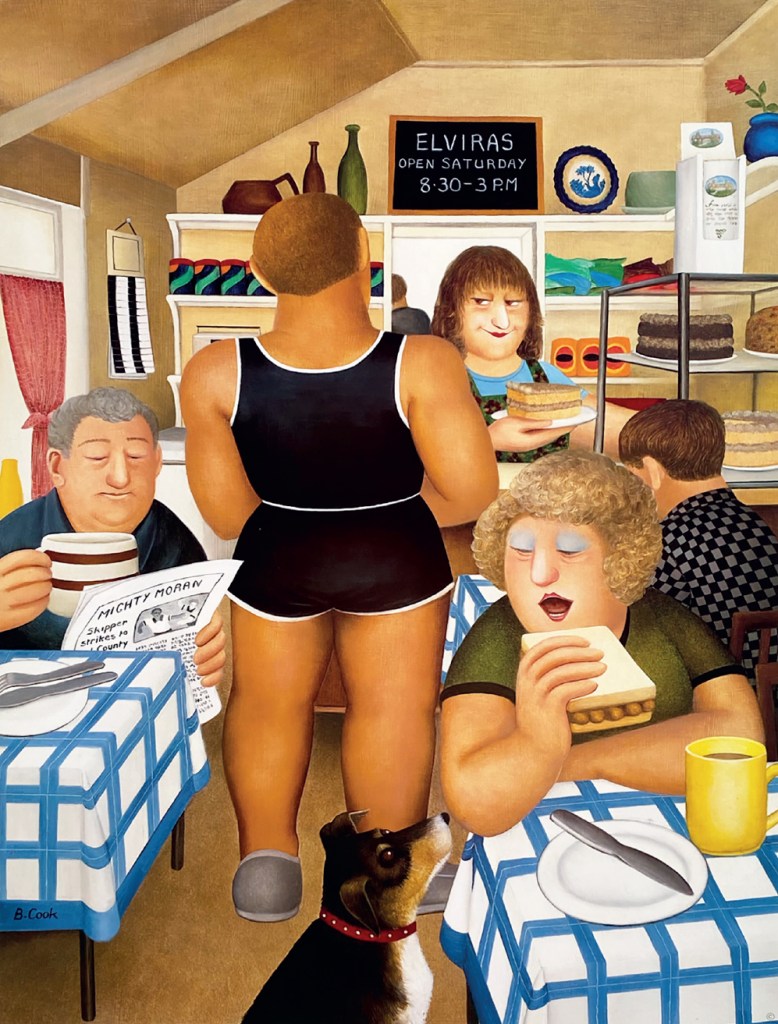

The brilliance of Beryl Cook

Nobody claims Beryl Cook was an artistic genius, least of all the artist herself. ‘I think my work lies somewhere between Donald McGill [the saucy postcard artist that George Orwell wrote so lyrically about] and Stanley Spencer,’ she once told me. ‘But I’m sorry to say I’m probably nearer McGill.’

She was, as ever, being modest. I actually think she’s nearer Spencer – and Hogarth, come to that. Cook’s paintings make us laugh but that doesn’t stop them from being art. (Few would say Shakespeare’s comedies are as profound as his tragedies, but they’re brilliant creations, nevertheless.) Though Victoria Wood dubbed her work ‘Rubens with jokes’, there aren’t actually any jokes in her pictures; they’re all direct observations, not double entendres.

‘I only paint when I’m excited by something, and what excites me is the joy in life’

I once asked Beryl if she’d ever wanted to paint something serious. She said: ‘I see things that horrify me, but I don’t want to paint them. If I thought that by painting something very meaningful it would change things, then perhaps I might… but I don’t believe that. So, I don’t. I think people are getting dulled by the amount of horror. I only paint when I’m excited by something, and what excites me is the joy in life.’

Her art sprung from nowhere. She’d given her son some paints for his birthday, and he painted a picture with grass at the bottom, a little house standing on it and a band of blue sky at the top. ‘But there’s nothing in the middle,’ Beryl complained. ‘There isn’t anything in the middle,’ he replied. ‘I’ll show you what’s in the middle,’ said Beryl, grabbing hold of a brush and another sheet of paper. She painted two great bare breasts and then added on top a head with eyes looking sharply to one side, as if to say, ‘What do you think you’re staring at?’ She had no idea how to paint a waist so painted a fence along the bottom with the breasts lolling over. Her husband dubbed the picture ‘The Hangover’.

She told me she was so surprised by what she’d done she felt as if she’d been kicked in the stomach. She’d no idea she could paint anything at all and knew nothing about art.

Two years later, sitting in her local pub, it suddenly occurred to her that she’d like to paint a picture of the people larking about (see above). She tried it, taught herself how to paint, discovered artists like Stanley Spencer, who made a huge impression on her, and then began to produce a lot of work, which she hung around the guest house she ran. Her local landlord suggested she should put them up in his pub. Reluctantly, she agreed. He then said she’d have to put prices on them. She thought this was a joke – no one would buy them, surely – but she put £25 on each, and they all sold.

One thing led to another: a show at the very enterprising Plymouth Art Centre, an invitation to join the Portal Gallery in London, national coverage in the Sunday Times and on Melvyn Bragg’s The South Bank Show on ITV. She soon became the most genuinely popular living artist in Britain.

There are many features that make her art distinctive: fat faces (they’re not self-portraits; Beryl was small, sharp-eyed and shy) and fat fingers (minus fingernails – Fernand Léger used the same modernising simplification), strong, bright colours and bouncing, curvaceous contours. But what makes them instantly recognisable is their design.

She composed with great precision. Her art always starts with a moment of inspiration, when something catches her eye and makes her want to do a painting. She then leads the viewer around the picture by following each figure’s gesture and expression. By these means, she sustains her initial heightened awareness throughout the composition. It is this overall orchestration that lifts her paintings out of time and makes them lasting.

Beryl never took commissions or worked as an illustrator; nor is her art in any way commercial, though it sold hugely in reproductions. Why then, since it’s genuine, creative and unforgettable, did it so get up the noses of the art establishment? Beryl herself said: ‘I can’t help feeling that if all these people like my pictures they can’t really be art. Art always seems to be something which only a few people can appreciate.’

Before the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art I created in Glasgow in 1996, Nick Serota (then director of the Tate) and myself were invited to give presentations at an international curators’ conference at the Louvre. Serota had had the go-ahead to build Tate Modern, after National Lottery money became available, with a budget of £135 million, as against my £6 million, a sum typical of pre-lottery funding for the arts.

I spoke about the role a gallery of modern art has to play in contemporary society, providing opportunities to see authentic, artistic creations with enduring potential. I showed them the sort of works we would be exhibiting, from Jean Tinguely, Henri Cartier-Bresson and David Hockney to Beryl Cook. As soon as I sat down (after laughter and applause), Nick rose from his seat in the front row, uninvited by the chairman on the platform, turned to our colleagues seated in the raked hall and solemnly announced: ‘There will be no Beryl Cooks in Tate Modern.’

I was a bit put out by this holier-than-thou public put-down, but also intrigued, for his remark precisely encapsulated the wrong turn I thought art galleries were taking, very much at Serota’s instigation. First, there was what came across as personal and professional arrogance. In 1995 Beryl was firing on all cylinders. What gave him the right to presume that she would never paint a picture of brilliance? Then there were the wider implications for modern art galleries as a whole. When the first of these, the Museum of Modern Art, was getting underway in New York in the early 1930s, Gertrude Stein reportedly said: ‘You can be a museum, or you can be modern, but you can’t be both.’ She was right. That’s why I prefer to call them galleries. No, art can’t instantly be of ‘museum quality’. It takes a while to sort out what are the truly telling creations of their time.

I’m all for curators embarking on this process, and involving the public in this act of sifting. The curators’ job is a humble one, to respond to what they see, keeping as open a mind as possible. All genuine works of art will inevitably be a surprise, if only because nothing (and no one) is ever the same.

During Serota’s reign at the Tate, which lasted more than a quarter of a century, modern art galleries, both in Britain and abroad, became both the determinators and terminators of what is and is not the officially accepted art of our times. They became pseudo-sacred spaces controlled and patrolled by a presumptuous priesthood of curators.

A select group of art dealers actively promoted this development, because it lined their pockets. When an artist’s work enters a museum, it is presumed to be part of the canon, and his or her output becomes, from then on, a gilt-edged investment – previously symbolised by the gold frames around paintings, when there were paintings.

The trouble is that much of the stuff in today’s modern art museums is mediocre, and a lot not even art. Found objects – the trend of our time – only become art when they’re put in an art gallery. Outside of that, they’re just a balloon dog or a pickled shark. Modern art museums have become phoney pillars of the establishment, fronting a huge cultural and financial confidence trick.

Genuine art is always a complete, imaginative creation, and doesn’t need an art gallery, let alone an art museum, to exist. The ‘Mona Lisa’ is the ‘Mona Lisa’ whether it is in the Louvre or on the street.

I have charted how this sorry farce came about, most recently in my book Art Exposed (Pallas Athene, 2023). The game reached rock bottom in 2000 when Nick Serota bought Piero Manzoni’s ‘Artist’s Shit’ (1961) for Tate Modern, one of an edition of 90 cans of ‘freshly preserved’ faeces (contents unexamined), for £22,000 – a sum that could, at that time, have bought a whole clutch of Beryl Cooks.

No one in their right mind wants to look at a can of excrement, but many would like to look at a Beryl Cook. And when they do, they won’t laugh at it, but with it.

Modern art galleries need to step back from the front row and enable the most genuine, original artists of our time to talk directly to the widest public again. The tide is turning, with the fashionable Studio Voltaire showing Beryl alongside Tom of Finland – a brilliant pairing. Add Fernando Botero to the mix and the trio could take Tate Modern by storm – and show just how blinkered Serota was.

Listen to Julian Spalding and Rachel Campbell-Johnston, former chief art critic at the Times, discuss Beryl Cook on The Edition podcast:

A gripping podcast about America’s obsession with guns

The love affair between so many Americans and their guns – long a source of international fascination – appears to be getting more painfully intense. The greater the publicity over gun crime, the more Americans think they’d better acquire a firearm to keep themselves safe. There are now roughly 400 million guns in the US – but most citizens feel more unsafe than ever, and with some justification. Last year featured both the highest level of gun ownership in US history and the highest recorded number of mass shootings.

This really is one to listen to in bed, in the pitch dark – even better, pretend you’re in a couchette

‘How did we get here, and how do we get ourselves out?’ asks Garrett Graff, the host of the Long Shadow podcast In Guns We Trust, which examines the trajectory of US gun ownership and the gradual sanctification of the right to bear arms. Graff owns a gun himself, has a subscription to Garden & Gun magazine, and grew up in the hunting grounds of Vermont, where ‘the first day of deer season was almost like a state holiday’. Still, he’s clearly worried. While guns were once chiefly tools for hunting, pest control and recreation, now they are most often purchased for personal protection – or, in the most horrific scenarios, for attack.

Attack is where the podcast opens: 25 years ago, in 1999, when two students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, opened fire in Columbine high school, Colorado, killing 12 fellow pupils and one teacher before turning the guns on themselves. This was not the first US school shooting, but it was the deadliest up to that date. The killers’ extensive documentation of their planning, and the ensuing media coverage, entrenched the massacre in other unhinged imaginations, spawning copy-cat attacks in the years to come.

What I’d forgotten – but that Graff explores – was the response of the National Rifle Association (NRA), scheduled to hold its annual convention in Denver, Colorado, the week after the shooting. The mayor asked the NRA to cancel, but the event went ahead, albeit a scaled-down version. Charlton Heston, the actor turned NRA president, made a speech in which he explicitly defied the mayor, reminding listeners his organisation was ‘a 128-year-old fixture of mainstream America’. Heard here, his resonant proclamation takes on a curiously sinister edge.

In fact, Graff reveals, there wasn’t a consensus in the NRA about holding the event: some argued strongly that they should delay or call it off. But a forceful voice against concessions was that of Marion Hammer, Heston’s predecessor as NRA president, who – despite being under 5ft tall – had an outsize talent for intimidating opponents and legislators. In later episodes Graff explores how Hammer, and another former NRA president, the late Harlon Carter, ramped up political pressure to turn the second amendment from a ‘constitutional afterthought’ subject to restrictions, to a ‘sacred right’ which, for many, went to the very heart of what it meant to be an American. It doesn’t reassure one to learn that Carter, at 17, was convicted of shooting dead a 15-year-old Mexican-American boy. Thus far this is a gripping podcast, providing a map for the evolution of a grim status quo.

A more poetic experience was to be found on Radio 4, where the writer Horatio Clare boarded a sleeper train from Paris to Vienna while reflecting on the role of the night train in culture and history. Except, he didn’t: that train was cancelled due to heavy snow at Munich, so he had to go via Frankfurt instead, which meant a lingering wait on a chilly platform in the small hours for a very late connection. Luckily Clare is of a meditative disposition, although his cheery acceptance, ‘I rather love these accidental, off-the-plan times’ did eventually give way to the poignant confession: ‘I’ve seldom looked forward to a train so much.’

En route the programme traversed the charms of the Gare de l’Est, a conversation with the author and railway enthusiast Andrew Martin, the faded glory of the Orient Express, and a friend of David Bowie reminiscing about his 1970s trip with the rockstar on the Trans-Siberian express, both shivering in their flimsy fashion gear. Later it rolled through more sobering territory of Holocaust transportations and the modern-day refugees boarding trains out of Ukraine.

Clare’s narration was often lushly romantic, recalling his arrival in Paris as a wide-eyed 17-year-old, but it fitted well with the spirit of its subject. And I know I’ve said this before – but this really is one to listen to in bed, in the pitch dark. Even better, pretend you’re in a couchette.

Does Interrailing hold the same heady magic for youth today? Catherine Carr’s timely, touching series of 15-minute investigations into the mindset of teenage boys suggests that they’re at home much more, worrying. Steeped in the internet, stalled by Covid and confused by porn, they talk about the social pressure to be strong, good-looking and well off while navigating conflicting social signals. ‘There’s a lot of weight on your shoulders,’ said one. Sadly, I don’t think he meant a backpack.

Yunchan Lim’s Chopin isn’t as good as his Liszt or Rach

Grade: B-

In 2022 the South Korean pianist Yunchan Lim became, at 18, the youngest winner of the Van Cliburn competition, displaying a virtuosity that stunned the judges. You could see conductor Marin Alsop’s astonishment as he bounded through the finale of Rach 3, combining accuracy and swirling fantasy at daredevil speed. It’s been viewed nearly 15 million times on YouTube. In truth, though, he’d have had to screw up badly not to win, because he’d already dispatched Liszt’s fiendish Transcendental Études with perfect articulation and mercurial wit; in places he out-dazzled even the current master of this repertoire, Daniil Trifonov.

Decca snapped him up and here’s his first studio album: both sets of Chopin’s Études. Again, Lim’s dexterity almost defies comparison. The most difficult étude is reckoned to be Op. 25 in G-sharp minor, whose finger-twisting thirds are hated by pianists because they expose the tiniest unevenness. Here they descend in perfect shining cascades; Lim’s dynamics reveal phenomenal muscle control. (It’s not surprising, but worrying, that he recently pulled out of a Wigmore recital with hand strain.)

But there’s something missing. Chopin weaves in delicious melodies; Lim is far too intelligent not to pick them out, but he doesn’t sing them. Even the steely Pollini leaned more into the melodies, and Alfred Cortot in his 1933-34 recordings does nothing but sing, albeit at the cost of a few smudged notes. You could say Lim falls into the trap of playing Chopin like Liszt. At any rate you’re better off listening to those miraculous Van Cliburn Transcendental Études, released last year by Steinway.

Fascinating insight into the mind of Michelangelo

You’re pushing 60 and an important patron asks you to repeat an artistic feat you accomplished in your thirties. There’s nothing more daunting than having to compete with your younger self, but the patron is the Pope. How can you say no?

Besides, it’s an excuse to get away from Florence, where your work for the republicans who expelled the Medici has become an embarrassment since their return. So you tell Pope Clement VII that, yes, you will move to Rome and paint a Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel.

Bladder stones, colic, backache, gout – Michelangelo had them all and moaned about them in letters

Contemplating this monumental fresco, it’s hard to believe that it was the work of a man already complaining of old age, but Michelangelo (1475-1564) was an artistic titan. That’s what makes the British Museum’s new show so special: by focusing on his last three decades, it demonstrates that even titans age. Bladder stones, colic, backache, gout – Michelangelo had them all and moaned about them in letters to his nephew. Italians, even titans, don’t have stiff upper lips.

This is not a show of Michelangelo masterpieces; it’s an introduction to how a great artist thinks. It includes some polished presentation drawings made in the early 1530s for his young pash Tommaso dei Cavalieri – with whom he was infatuated to the point of offering: ‘If you do not like this sketch… I have time to make another one’ – and some marvellous life drawings for the ‘Last Judgment’. But more fascinating are the jottings on the backs of sheets where we can read the artist’s first, second and third thoughts on different projects. Always careful with money, he used and reused every scrap of paper, sometimes even gluing irregular offcuts together.

Ideas came so easily to Michelangelo that he could afford to be generous with them. Increasingly overwhelmed with papal projects, mainly architectural, he kept importunate patrons at bay by throwing them scraps executed by collaborators. The show includes a few too many sugary paintings by Marcello Venusti after the master’s designs. ‘If it is yours, I want it from you at all costs,’ the discerning Vittoria Colonna wrote to him. ‘But if… you wish your assistant to complete it… I would prefer him to make something else.’

The close friendship Michelangelo developed with this devout widow and fellow poet came at a point in his artistic life when he was moving away from the muscular Christianity of his Sistine frescoes towards something more spiritual. The ‘Christ on the Cross’ (c.1538-41) he drew for Colonna is still a powerful figure, but in the drawings from his last decade at the heart of this show the emphasis is on frailty rather than power. In these late meditations on mortality and loss, the vigorous chalk-marks of the life drawings become the faintest touches, as if the artist is almost afraid to breathe on the paper. Gone is the muscular definition of the ‘Last Judgment’: defined and redefined by multiple outlines that make their hazy figures appear to tremble, these drawings don’t have vigour, but they have life.

Who did he do them for? In the absence of alternative evidence, it looks as if he made them for himself as acts of devotion. Towards the end he became increasingly concerned with the state and destiny of his soul: in 1554, aged 79, he sent Vasari a sonnet renouncing ‘the affectionate fantasy, that made art an idol and sovereign to me’. But it was too late to kick the habit. Instead, on the monastic principle ‘laborare est orare’ – ‘to work is to pray’ – he may have offered up these drawings as prayers. Their subject is closeness: closeness to death, and to loved ones. Michelangelo could be prickly, but he was not a loner. He formed warm relationships and was devastated by the loss of friends and assistants: on the death of his faithful servant Urbino in 1555 he was ‘so overwhelmed with emotion’ he couldn’t write.

In old age, memories of early childhood seem to have returned to a man who lost his mother at the age of six. A tender ‘Virgin and Child’ (c.1560-63) celebrates the bond between mother and baby, while other drawings focus on the mature mother-son relationship he never experienced. In ‘The Resurrected Christ Appearing to his Mother’ (c.1560-63) she is old and stout, having a sit-down; he flits in, insubstantial as a shade, and their extended fingertips echo the contact between God and Adam on the Sistine ceiling. If you’ve ever wondered what the resurrection of the body might look like, this drawing gives a convincing impression. But when he drew it, Michelangelo was still in the world of the living – a note at the top reminds him to contact a courier. The artist sanctified by Vasari – and the whole of subsequent art history – as ‘a being rather divine than human’ is exposed by this revelatory show as a man after all.

Across Britain punters are lapping up ultra-trad opera – the Arts Council will be disgusted

Another week at the opera, another evening with an elitist and ethically dubious art form. I love it; you love it; but the authors of the Arts Council’s recent report on opera in England are less enamoured. One issue they identified was that ‘the stories which opera and music theatre tells are failing to connect fully with contemporary society’. Possibly the memo never reached the promoters of Ellen Kent’s spring tour, which since January has visited 40-odd venues not typically served by major opera companies, and has done so without public subsidy. You might imagine that the only commercial outfit to make live opera pay in Wolverhampton, Ipswich and Sunderland would have featured prominently in the Arts Council’s research, but they don’t appear to have been consulted.

The tour has visited 40-odd venues not typically served by major opera companies – without public subsidy

Anyway, it’s a bit awkward because it seems the stories with which contemporary audiences in Stoke, Bradford and Southend are choosing to connect (at least, when it comes to spending their own money) are fully-staged, ultra-traditional revivals of romantic warhorses – Carmen, La traviata and Madama Butterfly. All thoroughly reprehensible, of course, and Butterfly in particular is the subject of grave concern at the subsidised companies. The Royal Opera hired cultural sensitivity consultants, like asbestos-removers, to decontaminate their ideologically-suspect Leiser-Caurier staging.

Meanwhile Ellen Kent’s version just keeps rolling along. Kent herself is credited as director, and if you’ve seen her production over the past two decades you’ll know the deal: paper-walled Japanese house, tatty backcloths and a bamboo water feature which trickles away – charmingly or maddeningly, according to taste – from first note to last. You get cherry blossom, kimonos and an adorable kiddywink playing little Sorrow. Barring some wear to the sets (it looked as if roof repairs were about to be added to Butterfly’s list of worries), very little seemed to have changed since I first saw it in 2006.