-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

In Mumbai, orchestras are playing western classics without apology

Choosing a concert opener is an art in its own right. Fashions shift: the traditional overture has fallen from favour in recent years, and you might go seasons now without hearing such one-time favourites as The Thieving Magpie or Euryanthe. The opening slot is more likely to contain something short and contemporary, or worthy and obscure (cynics call it ‘box-ticking repertoire’). Or it might be empty, tipping you straight into a symphony or concerto the way a Michelin-starred chef presents his signature creation – unadorned, on a bare white plate.

The Symphony Orchestra of India began its latest UK tour with John Williams’s ‘Imperial March’ from The Empire Strikes Back – and goodness alone knows why. Nothing wrong with playing film music in a symphonic concert, of course; more orchestras should do it. But such an ominous piece (it’s basically Darth Vader’s leitmotif)? Maybe it’s just something that the SOI and its guest conductor, Richard Farnes, enjoy playing together – a three-minute blast of Technicolor orchestration to get the fingers loosened up. It’s as valid a reason as any.

While we writhe in self-doubt, in Mumbai they’re playing western classics without apology

Then we were on to Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, with Pavel Kolesnikov as soloist, and a 45-minute symphonic suite of Wagner’s Parsifal, arranged by Andrew Gourlay. The following night in London, under Alpesh Chauhan, the SOI was due to play Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier Suite and Stravinsky’s Petrushka. That’s some serious bling. But if you heard this relatively young (it was founded in 2006) orchestra on its 2019 tour, you’ll already know that it’s a cracking outfit. Farnes’s programme offered something different: a chance to hear the SOI stretch out and sing in music where brilliance is never, in itself, sufficient.

It’s safe to say that they nailed it, if that isn’t too coarse an image for playing of such concentration and beauty. The opening horn call in the Brahms felt daringly slow and Kolesnikov – who presumably specified the tempo – responded with a solo that lingered, sighed and fell away; the woodwind response seemed to melt on the tongue. That’s one quality of the SOI – a woodwind section of quite extraordinary mellowness and musicianship. The flutes make a particularly ravishing sound; later, in the third movement, the first oboe, Richard Hewitt, responded with aching tenderness to Sevak Avanesyan’s noble cello solo. Another strength is the string playing. The SOI, like most major orchestras, is a multinational body, and in 2019 the Russian-flavoured sound of its violin section (largely recruited from former Soviet states) was very audible. They seem to have bedded in a bit since then. The golden tone and taste for expressive portamenti was not new, but the way they breathed and phrased together did seem like a more recent development. Possibly working with an opera conductor as experienced as Farnes has had an effect. The Brahms was simultaneously epic and intimate (Farnes and Kolesnikov maintained very spacious tempi throughout), and as for Parsifal: well, we know from Opera North what Farnes can achieve in this otherworldly music.

Any serious Wagnerian will have misgivings about filleted concert suites, though Gourlay’s arrangement was certainly tasteful (possibly too tasteful – I missed the Flower Maidens). But there could be no misgivings about the SOI’s response: the deep, solemn weight of the brass; woodwinds that billed and cooed with surpassing tenderness in the Good Friday music and, above all, the refinement and delicacy of those glowing strings. There’s a thought for next year. While western orchestras writhe in self-doubt, over in Mumbai – a city that practically defines the term ‘diversity’ – the SOI is pushing ahead with its mission to play the western classics without apology. There’s something to be said for believing in what you do.

Meanwhile, deep below Jermyn Street, the Charles Court Opera is presenting its annual pantomime, written and directed by the company’s artistic director John Savournin, with music by David Eaton. Last year it did Rumpelstiltskin, and apparently it was a knockout. This time it’s the Odyssey, and I still can’t credit that it’s possible to get belly-laughs out of the Eumenides. There’s a candy-coloured set, a small omni-talented cast (many familiar from CCO’s G&S productions, so they can carry a tune as well as deliver a gag), and – this being Homer, after all – a talking (and singing) horse.

Critics have been asked not to spoil the punchlines, but imagine being sat in a confined space and power-hosed with pop-culture gags (‘If you know this tune you’re over 40’ they sang at one point, and they weren’t wrong), ludicrously repurposed TV themes and enough groan-inducing classical puns to fill several Trojan horses and still have enough left over to hold the pass at Thermopylae. You have to be very smart to be quite this silly. Dust off your E.V. Rieu, and see it – you’ll thank me.

The horrors of dining with a Roman emperor

Emperor of Rome? Is there a typo in the title? Mary Beard’s latest book is about not one but 30 Roman emperors, from Julius Caesar (assassinated 44 BCE) to Alexander Severus (assassinated 235 CE), so why the singular? The answer is that Emperor of Rome is a study of autocracy and one autocrat, as Marcus Aurelius put it, is much the same as another: ‘Same play, different cast.’

Beard’s subject is emperors as a category, because it was the symbol of rule rather than the ruler himself that mattered to the 50 million imperial subjects between darkest Britannia and the Saharan desert in the first three centuries of the Christian era. Added to which, she points out, most of the population outside the metropolitan elite could put neither a name nor a face to the current ruler, a man simply known as ‘the Emperor of Rome’. ‘There are people among us who assume that Agamemnon is still king,’ said a 5th-century philosopher, reporting from North Africa. So don’t worry, Beard reassures her readers, if you can’t tell your Marcus Aureliuses from your Antoninus Piuses because no one else could either.

Domitian’s guests arrived to a dining room painted black, their places marked by imitation tombstones

Rome played to the public ignorance by literally blurring the emperors into one. Every time an emperor died, the features on his marble portrait were chiselled to resemble those of his successor, suggesting the seamless continuity of power. There is not a single image, Beard says, on coins, cameos, statues or sculptures, that looks remotely like any of the descriptions of the emperors given in the biographies by Suetonius. Not only would we never know from Domitian’s abundant head of hair that he was going bald (he even wrote a book on hair loss), but every imperial head was given by artists the same number of locks. The ancient historians, telling the same stories about different emperors, made them equally indistinguishable. The result was a period of such political stability that, as Beard puts it: ‘You could have gone to sleep in 1 BCE and woken up 200 years later and still have recognised the world around you.’

The aim of the bookis to expose what Beard calls ‘emperors of the imagination’, and explore the reality, and banality, of imperial life. Digging beneath the mythical portraits of rulers seen as either ‘good’, like Trajan (‘good in whose opinion?’), or ‘bad’, like Nero (‘bad by what criteria?’), Beard asks startlingly simple questions: ‘How, and why, have we come to characterise the emperors as we do?’ How was it possible to rule a vast empire with a skeleton staff? Why were so many emperors murdered? What were the rules, if any, of succession? Her interest is primarily in facts, but spin doctors – the invention of Roman government – offered important alternative facts, while fictions, in the form of gossip, slander, urban myths, even dreams, also have a part to play in Beard’s account, suggesting how the population imagined absolute and unending power to work.

So what were the emperor’s job requirements? Augustus, the founder of the Roman empire – who died of natural causes in 14 CE (unless, as was rumoured, he was poisoned by Livia) – left a useful roll call of his achievements in a manifesto which he had posted on the pillars outside his tomb. His boasting – ‘I did this… I did that…’ – reminds me of God in the Book of Job, but Beard, always alert to the contemporary analogy, compares Augustus’s list of newly built shrines, porticoes, theatres, piazzas and temples to a ‘Make Rome Great Again’ campaign.

How should an emperor live? We must see him, Beard stresses, in his habitat. She reconstructs the royal residence on Palatine Hill, taking us through its evolution from a compound of individual houses and dark alleys (in one of which Caligula was killed), to Nero’s Golden House, with its lake the size of the sea (it was probably, Beard suggests, a rectangular pool in a stone basin), to the Palace of Domitian, described by Roman writers as a greater wonder than the pyramids.

There is no better place to observe power than the dinner table, and no better place than imperial feasts for myths and legends to take seed. Emperor of Rome begins with the dinner parties hosted by the young Elagabalus (assassinated 222 CE), who reportedly sat his guests on whoopee cushions, served them green food, blue food, fake food or camels’ heels before smothering them in a deluge of flower petals. Really? Even Elagabalus’s Roman biographer, the source of the intel on his party tricks and lifestyle, conceded that most of the stories he gathered about the emperor (such as decorating his summer gardens with ice and snow) were probably concocted by the boy’s rivals and successor.

A chapter devoted to the semiology and sociology of Roman dining opens with an evening in the company of Domitian, whose guests arrived to find a dining room painted black, their places marked by imitation tombstones. The food, served on black dishes, was the kind offered to the dead. This party, reported in detail by the historian Cassius Dio, could be seen, Beard suggests, as a dictator’s flamboyant threat, or, less dramatically, as a stylish and witty fancy dress party, or simply as a philosophical reflection on mortality. It was important, as Seneca stressed in one of his essays, to prepare oneself for death.

And what about those lavish Roman menus? Elagabalus’s colour-coded food, Beard points out, could be interpreted either as deranged self-indulgence or refined haute cuisine. The signature dish of Vitellius was reported to be peacock brains and flamingo tongues, but it is more likely that the royal kitchens served the kind of dishes which could be easily consumed with one hand while reclining on couches. The Roman banquet, Beard suggests, would consist of something closer to tapas.

Emperor of Rome is the work of a lifetime, and a book to return to. Immersive, witty, alive on every page, it clarifies the past and illuminates the present. What can we learn from the emperors about autocracy? ‘That it is fundamentally a fake, a sham, a distorting mirror.’

Pleasant, underwhelming: Kurt Vile’s Back to Moon Beach reviewed

Grade: C+

Maximum points for self-awareness, you have to say. The title track of this pleasant, if largely underwhelming, album include the lines: ‘These recycled riffs aren’t going anywhere, any time.’ Never a truer word spoken.

Here, this fitfully engaging singer-songwriter shuffles through predictable chord changes pinioned by forgettable piano riffs and intones – deploying an often exaggerated southern drawl somewhat at odds with his Pennsylvanian provenance – basic and repetitive melodies which stay in the memory for about the half-life of Oganesson and then vanish.

There is a pleasing twang to the guitar, bursts of scuzzy bottleneck and the occasional lap steel, but the songs go nowhere, as Kurt is generous enough to admit. It is an album which lapses into self-parody within 30 seconds of the start of each track: the dolorous drawl, the familiar lack of scansion and the over-weening introspection.

He pays homage to the late Tom Petty on ‘Tom Petty’s Gone (But Tell Him I Asked For Him)’, but seemingly either doesn’t realise, or doesn’t care, that whatever Petty’s faults as a heartland songwriter, he was, in Robert Christgau’s words, a ‘catchy sumbitch’. Kurt can’t really do catchy. And he doesn’t, er, rock out, either.

Maybe it’s all worth it, at this time of the year, for ‘Must Be Santa’, which takes self-parody to lengths hitherto unimagined. ‘Who’s got a beard that’s long and white?’ asks Kurt and the girls reply: ‘Santa’s got a beard that’s long and white.’ Still no tune.

I know where Kurt Vile is coming from. But I haven’t a clue where he wishes to end up. And I’m not sure he has, either.

You’ll want all the characters to die: Infinite Life, at the Dorfman Theatre, reviewed

Infinite Life is about five American women, all dumpling-shaped, who sit in a hotel garden observing a hunger strike. Some of them haven’t touched food for days, some for weeks. ‘Don’t be afraid to puke,’ counsels one of the dumplings. ‘Puking is good.’ They pass their afternoons wittering inanely about nothing at all. One dumpling is an air hostess, another works in banking, a third has a job as a fast-food executive. Or so they claim. Each of the dumplings might be lying to the others but it would make no difference because nothing connects them, and they have no stake in the situation other than the desire to burn up time.

It doesn’t feel like a play but a prank staged by psychologists

After a while it transpires that the dumplings are not hunger-strikers but weight-watchers hoping to cure their many ailments by fasting. The main dumpling, Sofi, is troubled by an infected clitoris which makes her groin feel ‘like a blow-torch’. Whenever the chance arises, she treats her itchy genitals with a seven-hour sex marathon. Another dumpling tells a story about driving through a eucalyptus grove. That’s the end of the story, by the way. A third dumpling recites passages from the trash novel she’s reading. A fourth jabbers about Christian Science.

Sofi, who appears to be the best-educated dumpling, holds forthright views about sex and she announces that online porn is dominated by ‘enormous idiot rapists’. One night she leaves a hysterical message on her lover’s phone in which she describes being sodomised by a toasted Hispanic delicacy. Then she lies on her back masturbating.

After a few days a new dumpling – male, half-naked and white-haired – joins the fat farm. The other dumplings discuss the possibility that he’s a mirage generated by their calorie-starved and hallucinating minds. Sofi starts to flirt with the imaginary male and they form a bond over some photographs of a diseased colon. That’s the highlight of the show. Did their amorous conversation actually happen or was it a figment of Sofi’s fevered brain? Hard to say.

After two hours of stage-time, the dumplings pack up their belongings and leave, one by one. End of diet. End of show. None of the dumplings has shed any weight and none has acquired a suntan despite roasting for weeks in the California sunshine. Infinite Life doesn’t feel like a play but a prank staged by psychologists who want to see how much vacuous poppycock a paying audience will bear before they demand a refund. It’s rare to find a show that would be improved if the characters were to starve to death – but here it is.

The design is as drab and cursory as the script: the dumplings lie on grey loungers surrounded by concrete walls painted magnolia. Their dreary, shapeless costumes look like rejects from a jumble sale, but it’s possible that the actors were told to slob into the theatre wearing whatever tat they crashed out in the previous night. As for the dialogue, it might have been improvised on the spot.

This lazy, brain-dead anti-drama originated in America where theatre-makers seem to hold their audiences in utter contempt. The National should set an example and not sink to the worst artistic standards in the world.

The panto at Stratford Jack and the Beanstalk starts as a Brechtian allegory about the toiling masses of ‘Splatford’ who extract bilge from nearby mudflats which is then sold by capitalists as a beauty product. After this brief Marxist introduction, the panto proper begins. The setting is a shop run by Milky Linda, a cross-dressing dairy magnate, who fears that her business is about to fold. Milky Linda is terrorised by two gormless thugs, one called Flesh Creep who wears leather clothes, and the other called Bill, whose looks are marred by a missing tooth and a cheap ginger wig. Milky Linda puts her faith in her drippy son, Jack, and his best friend, Winnie the Moo, who provides milk for the shop. Given that the show is aimed at kids, the narrative set-up is very elaborate – and we haven’t even reached the magic beans, the horrible ogre and the golden eggs. Maybe kids don’t much care.

My companion, River, aged eight, seemed to enjoy this scruffy, slapdash show with its queasy colour scheme of yellows, greens, blues and purples. The designer, Lily Arnold, covers too many of the props and costumes with lettering. It’s a panto you read rather than watch. ‘Look at the foxes,’ I said to River as three actors appeared dressed as furry urban scavengers. ‘That’s a hedgehog, a badger and a wolf,’ he corrected me. The outstanding performer is Savanna Jeffrey (Winnie the Moo), who acts very well and sings beautifully. I asked River for his final verdict. ‘Brilliant, average, or rubbish?’ I suggested. ‘In the middle,’ he said. ‘I quite liked it but I might see better.’

Will the Caucasus ever be tamed?

How to get your head around that searingly beautiful but complicated land that lies between the Caspian and Black Seas? The early Arab historian Al Masudi called the Caucasus jabal al-alsun, the mountain of tongues, and through the centuries the place has certainly seen its fair share of peoples, many of them troublesome, many of them troubled. Indeed, for somewhere you might think would be a transcontinental backwater, its outcrops, secluded valleys and expansive plains usefully separating its formidable neighbours – Russia to the north, Turkey and Iran to the south – it’s proved remarkably busy over the centuries; also persistently relevant. The turbulence of the region is rarely far from the news. Chechnya comes to mind – its two separatist wars – and Azerbaijan (upheavals in Nagorno-Karabakh), not to mention Moscow’s determination to make good its hold over Georgia.

After the ravages of the Black Death came the bloody conqueror Timur, who invaded no fewer than eight times

Put another way, the Great Caucasus Range provides a natural divide between east Europe and west Asia – yet even this barrier has failed to keep parties of either side out. Rather the opposite; the Caucasus proved a veritable thoroughfare of jealous warlords even before 1220, when the Mongols swept through, overpowering the Armenian army and all but breaking asunder the flourishing kingdom of Georgia. This was a prelude to more devastation in the form of the Black Death. Next came the bloody conqueror Timur, who invaded no fewer than eight times. So, when asked to review a history of the Caucasus, I might have been forgiven for hoping it would turn out to be a handy explainer, a neat little guide to clarify just who brought in what or did what unspeakable deed to whom.

I have to tell you, a handy little guide Christoph Baumer’s book is not. Weighing in at a couple of kilos, this second, concluding volume is more like those gloriously illustrated family-atlas-sized publications meant to tie in with a major exhibition at the British Museum. There are appendices – population stats, tables of languages, dynasties – and various indexes (of ‘concepts’ as well as people and places). At first glance, it is not a book that will appeal to those who like to curl up with a finely spun historical narrative – I’m thinking of William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain or my cousin Charles Allen’s Duel in the Snows.

Yet, as it turns out, it zings along. It’s a splendid achievement – informed, considered and clear. Though the fieldwork activities of the Swiss author are all but absent from the narrative, we soon understand that he’s an old hand on Central Asia and a worthy successor to a longstanding tradition of questing Europeans who have excited our imaginations with their tales of desert crossings astride Bactrian camels and of cities lost to the shifting sands. Baumer brings to mind the topographer Sven Hedin, the bespectacled Swede who mapped, among other things, the Wandering Lake of Lop Nor. One also thinks of explorers such as Nikolay Przewalski, he of the stocky wild horse, Francis Younghusband and Aurel Stein, who filled in blank charts and, unwittingly or not, became protagonists or pawns in the Great Game – not to mention the indomitable missionaries Mildred Cable and Evangeline French, and adventurer-writers such as Ella Maillart and Peter Fleming (his News from Tartary). Each in their own way told of passing through the wider region, but always with the same backdrop, the ruined splendour of those who had been before – the lichen-clad fortresses, rock tombs and broken monasteries on wind-harried crags.

There’s certainly no shortage of fascinating material, beginning around two million years ago, when into these realms spilled the first humans from Africa – not so much Homo habilis, our handyman ancestor, but Homo georgicus, Georgian Man. From then on, it was all action – the Neanderthals and in due course the northern horse peoples, Assyrians, Greeks, Anatolians, you name it. Wave upon wave they came, on foot, horseback or in war chariots, leaving behind pockets of survivors, each with their particular prejudices. Baumer enthrals us – more fallen towers, more fallen heroes – right to the present, with the states that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union, such as Azerbaijan with its huge oil revenues.

Here he takes quite a risk, casting an eye to the future in a section entitled ‘Outlook’. Given the simmering way of the Caucasus both north and south, I’d have omitted that bit, and perhaps the more fanciful illustrations. In Volume I, published two years ago, I recall a bunch of Palaeolithic characters wearing surprisingly natty suits of animal skins depicted chasing goats off a cliff. In this volume, a centurion waves his gladius, a short, stabbing sword, before the assembled ranks, as the Roman army readies itself for battle. But these renditions of the past are few and far between, and the photographs are spectacular. Once in a while there comes along a book by a fellow explorer that you wish to heaven you’d had the wherewithal and body of knowledge to write yourself. This is such a book.

Fine for the kiddies, given they’re clueless: Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget reviewed

The original Chicken Run (2000), which is generally considered the best riff on The Great Escape ever made starring stop-motion poultry, did not require a sequel – but here it is anyway. Now you’ll probably expect me to say that Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget isn’t a patch on the original so I will: it isn’t. It’s not bad-bad. It’s definitely something you can stick the kids in front of, given they don’t know any better. But it’s not nearly as inventive or funny or affecting and, while Aardman films have always looked and sounded like no other, this has a generic rather than a quirky, handmade feel. Chances are you’ve had bigger disappointments in life, but it is a disappointment all the same.

Chances are you’ve had bigger disappointments in life, but it is a disappointment all the same

Directed by Sam Fell with a screenplay by Karey Kirkpatrick, John O’Farrell and Rachel Tunnard, we find our chicken pals just where we left them: happily living on an island, having escaped from the evil Mrs Tweedy and her pie-making venture. The island is a utopian paradise and brightly, cartoonishly colourful in a way that the original wasn’t. That opened darkly, with the chickens imprisoned in a second world war-style concentration camp and before we go on, might I offer you a word of advice? Don’t re-watch the first film prior to starting this. It is not a good idea.

This time, Rocky is voiced by Zachary Levi instead of Mel Gibson, understandably, while Ginger is voiced by Thandiwe Newton instead of Julia Sawalha, inexplicably. They hatch a baby, Molly (Bella Ramsey), who has pluck, you could say, and grows up wanting to explore, like Simba from The Lion King, who also needs a good telling off. Molly escapes to the mainland where she is immediately entranced by the ‘Fun-Land Farm’ lorries with their pictures of happy-seeming chickens sitting in buckets painted on the sides. ‘I want to live in a bucket!’ she squawks excitedly. Usually these chickens are wonderfully endearing but Molly may well get on your nerves. A clip round the ear and to bed with no supper, if she were mine.

Fun-Land Farm, it turns out, is a Bond-like lair run by our old enemy, Mrs Tweedy (Miranda Richardson), who now brainwashes her chickens via specially controlled collars so they go to their deaths in a blissed-out state. (It makes the meat taste better, she says in her sales pitch to a fast-food chain.) This is where Molly ends up and whereas the last film was all about breaking out, this time Ginger, Rocky and co. must break in if Molly is to be saved from becoming a bucket of nuggets. It’s intended, I think, as a spoof of films like Mission: Impossible, but it doesn’t send them up so much as emulate them, so it’s action set-piece after action set-piece after action set-piece, over and over. Surely we’ve earned a chunk of downtime, I kept thinking. But no, they were always on the move, and once you’ve witnessed them seeing off a security guard once, twice, a third time, do we need to see it for a fourth? The narrative is thin.

What we must want from Aardman is a certain Britishness – might we not have had chicken in a basket instead of a bucket? – and that human touch, right down to visible thumbprints in the clay. True, the stop-motion is immaculate but the backgrounds are now CGI and this has a flattening, Disneyfying effect. Meanwhile, the characters are so in service to the action sequences that too little attention is paid to their personalities and while there are a couple of good jokes, there aren’t nearly enough. Maybe I’m being too harsh. It’s fine for the kiddies – or anyone else who doesn’t know better.

David Starkey on the inventor of the portrait

On 12 November 1549, the 12-year-old Edward VI, newly liberated from the tutelage of his overweening uncle, Lord Protector Somerset, was at last able to enter his father Henry VIII’s private apartments in the Palace of Whitehall. From the extraordinary mixture of treasures and bric-à-brac he found there, he chose one thing: ‘a book of patterns of physiognomies’ by his father’s court painter, Hans Holbein, who had died in 1543.

Edward was already familiar with his fellow European rulers from their portraits in the long gallery at St James’s, which seem to have been labelled and arranged as a teaching tool for the boy. Now, on the threshold of power, he wanted to familiarise himself with the establishment of Tudor England.

The word ‘portrait’ was unknown in the early 16th century. It entered the language thanks to Holbein

But there was a problem. It’s familiar to anyone who has opened a box of family photos and looked in bewilderment at the jumble of unknown faces: the drawings were unnamed. In similar circumstances, and at the same age as Edward, I turned to my mother; her identifications are still scribbled on the back of all too few of the photos in my childish hand. The orphaned Edward turned instead, as he so often did, to his favourite tutor, John Cheke.

By a series of extraordinary flukes, Holbein’s drawings with Cheke’s identifications are still in the Royal Collection and a selection of about half of them is on display in the Queen’s Gallery, together with a contextualising handful of Holbein’s finished portraits and a plethora of other gorgeously coloured and extravagantly formed Tudor artefacts from Hampton Court and Windsor.

The result is that the visitor can experience the same delight as Edward did on that November day almost 500 years ago: of drawings taken from life, which still seem to live and make their sitters live as well.

Kate Heard, the senior curator of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, who has organised the exhibition, is a subtly effective guide, nudging you to look closely at how Holbein achieves so much with so little: a licked finger wiped through black chalk to make a highlight in the glossy fabric of a ruffled sleeve; a dash of white on a cheek or a forehead to indicate the sheen of a beautiful woman’s skin; a dab or two of black ink to catch the thickening hair in the nape of a man’s neck; persistent jabs of the pen to get the cast of an eye or the profile of a nose exactly right. Thanks to Heard’s gentle prodding, I have never looked at the drawings more closely – not even when I handled them loose in their mounts back in the 1970s in the Royal Library at Windsor.

Heard is also an effective supplement to Cheke as a guide to the identity of the sitters. She summarises carefully an accurately the accumulated scholarship of generations, and pays generous tribute to her predecessor, Jane Roberts, whose near 40-year stewardship of the Print Room at Windsor did so much to facilitate access – including my own – to the drawings.

Which makes it even nicer that two of my re-identifications of the sitters from that period – Anne Boleyn and James Butler, Earl of Ormond – are accepted here. There’s also an interesting discussion of why Anne as Queen of England should have been portrayed in the process of dressing. I had suggested the reason was that Holbein had to catch some of his sitters first thing in the morning in their busy and important lives; Heard has the altogether more intriguing idea that the drawing was intended to serve as the basis for an intimate and come-hither miniature of Anne for the still-lascivious Henry.

Thus far, well and good. Even very good. But it doesn’t go half far enough – because the minute focus on the drawings effectively turns Holbein into a miniaturist. Now, he was a literal miniaturist; and of the highest quality, since his miniatures can be blown up big and still survive. But he could also, as only the greatest artists can, operate on a monumental scale – and on everything in-between.

You would scarcely know this from the exhibition. You would never grasp his astonishing originality either. Because even the title of the rather bland introductory essay to the catalogue diminishes him. It’s called ‘Portrait Artist at the Tudor Court’. But the word ‘portrait’ was unknown in the early 16th century (hence Edward’s ‘book of physiognomies’). It entered the language only under the Stuarts. And it did so largely thanks to Holbein: in other words, Holbein wasn’t any old portrait painter; he was (in England at any rate) the inventor of the portrait.

His coadjutor was the man who introduced Holbein to England: the great Dutch scholar Erasmus. This is because a principal inspiration for the new interest in the individual face came from Roman funerary sculpture. Which meant that the words usually inscribed in some form or another in the finished picture were almost as important as the image. As was the idea of memorialisation.

There was an opportunity to deal with all this though van Leemput’s copy of Holbein’s vast mural of the Tudor dynasty, that was destroyed in the Whitehall fire of 1698. But it is badly fluffed. Not even the magic of Holbein’s full-length Henry VIII is explained. ‘The only king whose shape you remember’, as my mentor, Geoffrey Elton, memorably declared in his Cambridge lectures long ago.

Finally, the claim that Holbein cannot be pinned down religiously is perverse: he began in the household of Thomas More during his first visit to England, but flourished in the circle of Thomas Cromwell during his second. Because, like Henry himself, he had converted. Only the genius of his art remained the same and shaped the contrasting images of those two great opponents, More and Cromwell, for ever.

A Nativity that sends shivers down the spine

Hieronymus Bosch was not a natural painter of religious images. His terrifying visions of Hell may have helped to keep congregations on the path of righteousness, but they did not inspire feelings of devotion – which could explain why none of the large altarpieces he painted remained over their altars after his death. In the eyes of the church, his Last Judgments were titillating: one painting showing ‘monstrous creatures from the underworld’ was removed from a church in his native ‘s-Hertogenbosch during his lifetime by officials offended by its orgy of nudity. Even his ‘Adoration of the Magi’ (c.1494) did not stay long above the Antwerp altar for which it was painted; it was snaffled by Philip II for his collection and now hangs with ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, and ‘The Haywain Triptych’, in the Prado.

This ‘fourth king’ has crashed the baby shower with dodgy-looking mates who are crowded behind him

Devotees of surrealism who make the pilgrimage to Madrid to worship before these two famous paintings don’t tend to linger over the master’s ‘Adoration’ which – with its dearth of monstrous creatures – appears disappointingly conventional. At first glance it has all the standard ingredients: dilapidated stable, splendid kings, sweet-faced Virgin and Child and, around the corner, a dutiful Joseph – in the absence of a midwife – drying the towel used at the birth over a fire.

So far, so relatively traditional. On closer inspection, though, some elements are missing – there are no angels and, mysteriously, no ox. But more disturbing than these omissions is the addition of what appears to be an extra king. Standing inside the entrance to the stable, between the black king Balthasar and the other two, is a curious figure in a bizarre headdress wearing an off-the-shoulder red cloak and very little else (detail of the central panel below). His face and neck are tanned but the rest of his body is deathly pale, and he has an oozing wound on his right leg encased like a reliquary in a crystal sheath. Between his legs a bell hangs on a ribbon embroidered with frogs, and in his left hand he holds a helmet resembling a papal tiara which seems to belong to Melchior kneeling in front of him. The tiara is decorated with a frieze of little trolls tormenting some herons – one of which bites back – while his own headdress is wreathed in a crown of thorns and topped by a crystal tube in which the thorns are blooming. Unlike the three kings who – apart from Balthasar with his page – are unattended, this ‘fourth king’ has crashed the baby shower with a gang of dodgy-looking mates who are crowded into the stable behind him, where – judging by the fire and soup bowl in the murky background – they appear to have set up camp.

Who is this pantomime villain with his consigliere, a horrid old man with a purple face and bright red nose? He is the Antichrist, the false Messiah sent to mislead the Jews in punishment for their failure to recognise the true one, and he is indulging in a bit of Christological cosplay in his red cloak and crown of thorns mimicking the Passion. Painted over a previous figure of an elderly man leaning on a staff, it’s possible that this intruder could have been added at the request of the painting’s commissioner Peeter Scheyfve – who appears on the left wing with his patron Saint Peter, across from his wife Agneese de Gramme with her patron Saint Agnes on the right – but the note of devilry he strikes smacks of Bosch. Even when heralding the birth of the Saviour, Bosch can’t resist sending shivers down the spine.

Even when heralding the birth of the Saviour, Bosch can’t resist sending shivers down the spine

In Christian eschatology the Antichrist is a charlatan who uses magic tricks – like making dead thorns bloom – and money to deceive and corrupt the three kings of the world (rulers of the three known continents), thereby unleashing the turmoil that precedes the Second Coming. Over the head of the false prophet, a tuft of straw tied to the gable truss fans out in rays like a fake star, a shoddy knock-off of the celestial body announcing the genuine Saviour’s birth in the sky above. With his jester’s bell the Antichrist looks like a fool, but Bosch warns that we laugh at his wiles at our peril: he is as dangerous, he hints, as the unblinking owl in the shadow of the gable above his head with the lizard in its claws.

Not content with admitting this spectre to the Nativity feast, Bosch even dares to cast shreds of doubt on the three kings. Their attitudes are respectful and their gifts are scripturally on-message, but the devil is in the detail. Caspar’s gold ornament portrays the sacrifice of Isaac, prefiguring Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, but it stands on a base supported by toads. Balthasar’s pot of myrrh is decorated with an image of the peace-making Abner kneeling before David, and the phoenix perched on its lid with a pomegranate seed in its beak is a portent of the Resurrection, but the border of his page’s robe is embroidered with the demonic motif of a fish with legs – the only monster to appear in the picture. Bosch doesn’t let us forget that the kings are pagan, and they’re not the only ones under suspicion. The behaviour of the shepherds – also added as afterthoughts, like the Antichrist – seen scrambling up a tree and clambering onto the roof for a better view, is less than reverential. They haven’t come to adore the Christ Child; they’ve come to gawp. Only one, peering through a hole in the stable wall with a grave expression, seems to have grasped the momentousness of the occasion.

These disrespectful yokels aren’t even good shepherds: they’ve left a sheep at the mercy of two wolves, seen mauling a man and pursuing a woman in the background landscape on the triptych’s right wing. The miracle taking place outside this stable hasn’t permeated to the wider world. On the left wing, behind the figure of Joseph, a Hammer-Horror gothic arch topped by a hand-standing frog leads to a field where ribald peasants dance rambunctiously. From the posture of one peasant and his partner’s reaction, you’d swear he was exposing himself (if so, he must be the only flasher in an altarpiece). In the centre, behind the stable’s pitched roof, a monkey riding a mule is pulled towards an inn identified as a brothel by the swan on its banner. Christ may be born in Bethlehem, but life goes on.

On either side of the roof, meanwhile, two bands of warriors advance from opposing directions; another band rides out from the cover of a hill behind. Unlike the traditional trains of attendants attending to the three kings, these armed bands are clearly looking for a fight. Some historians have identified them as Herod’s soldiers out looking for the baby Jesus, but they could also represent the warrior hordes heading for the final showdown at the end of days: the ‘kings of the earth, and their armies’ from Revelation. On the far horizon, behind a high wall, glimmers a weird and wonderful vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem. It’s a long way there, over desert terrain roamed by wild beasts and marauding armies, but the hope is that, thanks to the miracle revealed to the three kings, humanity may eventually make it.

Bosch celebrates redemption, while reminding us that salvation is not in the bag. His ‘Adoration of the Magi’ is a morality panto with a warning message that the world is full of false prophets and tricksters – the Devil’s emissaries are present even at the Epiphany. You feel like shouting to his three kings: ‘Look out, they’re behind you!’

Hunter Biden’s MAGA attack won’t throw Republicans off the scent

Hunter Biden was lost and now he’s found. That was the subtext of the president’s prodigal son’s speech outside Congress yesterday.

‘For six years, I have been the target of the unrelenting Trump attack machine shouting ‘Where’s Hunter?’,’ Hunter Biden told reporters. ‘Well, here is my answer, I am here.’

If Hunter’s statement was meant to put the Republicans on the back foot, it did not work. House Republicans James Comer and Jim Jordan vowed instead to launch contempt of congress proceedings against Hunter. Hours later, the thin Republican majority in Congress voted to formalise its impeachment inquiry into Joe Biden. The impeachment inquiry process, Republicans insist, will give Congress the power it needs to force the Biden family to answer questions it doesn’t want to answer.

For all of Biden’s ‘nothing to see here’ patter, the GOP House Committee has produced convincing-looking evidence

In his extraordinary remarks yesterday, Hunter Biden emphasised his contempt for the ‘MAGA-right’. He accused Republicans of maligning him and his father ‘for political purposes,’ which is obviously true.

Republicans have spent the last three years in Congress and elsewhere trying – not altogether without success – to establish that ‘the Biden crime family’, as Donald Trump likes to put it, was using the now president’s political clout to sell influence abroad. They also allege, on somewhat thinner ground, that ‘big guy’ Joe was involved in Hunter’s schemes himself.

Team Biden’s tactic in response has generally been to refuse to engage. Hunter, for instance, has been defying a Republican subpoena to attend a closed-door session of their House Committee investigation into his business dealings. Yesterday, however, he upped the ante.

‘(The MAGA-right) have lied over and over about every aspect of my personal and professional life, so much so that their lies have become the false facts believed by too many people,’ he said.

‘Let me state as clearly as I can. My father was not financially involved in my business, not as a practicing lawyer, not as a board member of Burisma, not in my partnership with the Chinese private businessman, not in my investments home nor abroad, and certainly not as an artist.’

Hunter said he would be willing to testify publicly. ‘I am here today…to answer any of the Committee’s legitimate questions… (But) Republicans do not want an open process where Americans can see their tactics, expose their baseless inquiry, or hear what I have to say. What are they afraid of? I am here. I am ready.’

In reply, Jim Jordan pointed towards Hunter’s statement that his father was not ‘financially involved’ in his business dealings. ‘That’s an important qualifier,’ said Jordan. ‘What involvement was it? That’s why we want to ask these questions with important witnesses and that’s why this resolution is important.’

The Republicans say they needed to formalise their impeachment inquiry because the White House has been refusing to cooperate with their congressional hearing on the grounds that it is ‘unconstitutional harassment.’ Now that the House has voted in favour, that defence appears to have gone.

After the vote, president Biden issued a lengthy statement calling it a ‘baseless political stunt.’ He said:

‘I wake up every day focused on the issues facing the American people – real issues that impact their lives, and the strength and security of our country and the world. Unfortunately, House Republicans are not joining me.’

But that, as he should know, is the wicked lesson you teach, when you practise to impeach. The Democrats spent four years hounding Trump through congressional inquiries, many of them spurious. They impeached him twice. Revenge was almost inevitable.

And, for all of Biden’s ‘nothing to see here’ patter, the GOP House Committee has produced convincing-looking evidence – including bank statements showing payments from foreign entities and testimonies from Hunter’s former business associates – to suggest that the Biden family is not as purely committed to public service as it makes out.

If all these allegations are baseless or fraudulent, the Biden family is doing a bad job of proving that’s the case.

Hunter can keep accusing Republicans of lying, of ‘cherry-picking’ facts for nefarious reasons. He can keep issuing mawkish statements about how the Grand Old Party has ‘taken the light of my dad’s love for me and presented it as darkness.’ But that won’t stop the Republicans digging.

Another by-election looms for Rishi

Poor Rishi Sunak just can’t catch a break. Every time he tries to establish a new narrative, one of his MPs triggers a by-election that gets us talking about the same old Tory woes. Today it’s the turn of Blackpool backbencher Scott Benton. He was the MP caught on camera by the Times in April, allegedly boasting about lobbying ministers for cash to a gambling firm. Since then he has sat as an independent MP, pending an investigation by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards and subsequent approval by the Standards Committee.

Today their verdict was published and it doesn’t make for happy reading. Benton is facing a 35-day suspension from the Commons. That is much higher than the minimum 10-day suspension needed to trigger the recall process, though much less than the 100-day sanction slapped on Boris Johnson earlier this year. If MPs agree with the committee’s findings, it will mean a recall petition and a likely by-election in 2024. Benton won Blackpool South in 2019 off Labour with a majority of just 3,690: a figure that looks very much reversible in the current climate.

A new year but the same old woes: how many more by-elections will we see before 2024 is out?

Cornwall’s fishermen are being drowned by bureaucracy

Bill Johnson is the assistant harbour master in Mousehole and skipper of the pilot Jen, a small boat of the inshore fleet. I know him because in summer, when tourists fill the tiny harbour with pleasure craft, he stands on the wharf offering conversation and advice. He is, of course, regarding the wreckage of Mousehole as a centre of the pilchard industry and home to Cornish people. A century ago, the harbour was a forest of masts: now just six fishing boats sail out of here. The rest are kayaks and paddleboards. But Bill is a kindly man, and he smiles on them.

Fishermen were poster boys for Brexit, much lauded, discussed and used. It was easy to persuade them to the cause: fishermen understand freedom. They crave it, rising at dawn to chase the fish, and again at dusk, when the fish bite up again. But the promised six-mile limit hasn’t materialised yet, licences are a nightmare of bureaucracy and avarice, regulation is chaotic and expanding, and the seafood industry hasn’t recovered from the paperwork Brexit brought. Even so, the Cornish inshore fleet of small boats hasn’t suffered a blow as grievous as the one Bill wants to talk to me about: the medical certificates imposed at the end of November. Master fishermen might labour under bureaucracy, they might be poorer, they might grumble about this and that, but they never imagined a Conservative government would stop them fishing.

Regulation is expanding, and the seafood industry hasn’t recovered from the paperwork Brexit brought

I meet Bill in the Old Ship on Mousehole harbour. He grew up in Paul, the village on the hill, and moved here when he was 17. He crabbed part-time while working as a gardener, then moved to a big boat. ‘That’s what you do here. You just fish.’ Fifty years ago, his first pay packet was £250, more than seven times his gardening wage: a fortune. ‘There was a lot more freedom on what we could catch and what we could land,’ he says. ‘We could land any fish we caught.’ Now he fishes for ‘anything you can get over the rail and sell at the fish market. Pilchards, red mullet, pollock, bass, cod and hake.’ As the sea warms, Mediterranean fish are coming: red mullet, bream and octopus. Mackerel is moving north to colder water, but tuna chase them. Crayfish, crabs and lobsters are declining. Fishermen are adaptive by nature. They have to be.

Bill’s trajectory is common: older fisher-men use smaller boats. But since Brexit, which promised an end to bureaucracy, they are drowning in the same bureaucracy that big boats need. Bill must record his catch on an app when he is still at sea. ‘If it’s more than 10 per cent out, I can be prosecuted. I have to weigh it on the boat – it’s impossible. The app doesn’t work here of course.’ It’s easy on a big boat with a big catch, he says, but for him, with ‘ten species of 500g apiece, not so much’.

There are new safety codes written by people who don’t understand boats (though there are grants for upgrades). There are trackers, but implementation has been chaotic, with approval for certain suppliers being withdrawn. (Again, there is a grant, but not everyone has the money to lay out.) They are worried about cameras on boats coming next, which is absurd: these are boats that rarely fish out of sight of land.

By far the worst threat is the medical certificate: the dreaded ML5, valid for five years, or one year if you are over 65. It’s part of a 2017 international convention that Ireland, for instance, has opted out of. Without the ML5, the fisherman will not be able to sell his catch. This will consign the elder fisherman to a dystopia which I, an outsider, find extraordinary. He will be a tourist in his own land, yet deprived of means. Bill had a triple heart bypass: he fears he will not pass.

Others fear this too and are already leaving. Bill knows an elderly fisherman at Penberth who gave up because he couldn’t work the app. Another left because he feared he was going to fail the medical. He will keep his hand in by making nets. Hundreds of small boats are for sale all over Britain. Bill notes ‘the stress that it’s having on people. Such a long wait to lose their job, lose their livelihood.’ The average wage of an inshore fisherman is £20,000 a year, but fishermen are gamblers. You could net £1,000 of bass before breakfast. If it’s stormy and no one else is out, prices go up. There’s always one madman. Now he will have to work in Lidl, or not at all.

They lobbied, but were told it was unfair to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. The RNLI, of course, is crewed by fishermen, who would rather be picking up fishermen than kayakers who paddle to Lamorna on a rising tide and can’t get back. Bill says there hasn’t been a shout for a fisherman with an underlying condition in a small boat as far back as he can remember. Usually it’s French trawlermen chopping their arms off, or people who buy blow-up paddleboards in Lidl: ‘Next thing they are six miles off, being brought back. There are more shouts for the lifeboat from the, er, leisure industry than from the commercial industry.’ He’s being polite. There’s a letter of commendation on the wall of the Sennen lifeboat house congratulating the coxswain on not punching a kayaker who, though his life was in danger, didn’t want to get in the lifeboat because he thought knew better than the coxswain. (That was the subtext at least. I wonder if the kayaker was a civil servant.)

Bill understands safety at sea. He served on the Solomon Browne. ‘It’s usually a commercial fisherman that sees the distress and raises the alarm to get them [paddleboarders and kayakers] saved,’ he says. ‘The more eyes out there, the safer it is for everyone.’ And, he adds: ‘It’s safer to have a heart attack on sea than land and wait for an ambulance.’ The ambulance wait times here are as notorious as the Dogs of Scilly: they are more likely to kill you.

All this makes no sense to the fishermen, who understand that a government that promised freedom is now taking the remnants of it away, and for what? Fishing, Bill says, is an avenue to well-paid, independent work. But few lads want to work in an overregulated industry. The small boats do less damage to the seabed and fish stocks. Beam trawlers are ‘raping and pillaging the seabed. Deep sea netters are hammering the grounds.’ Big crabbers have so many pots that they lose them, and lost pots are filled with ‘ghost fish’, lobsters that are never pulled upand die in the pot. Young lobsters go in to eat the dead and suffer the same fate. It’s a meta-phor for the treatment of the inshore fleet, I think: pointlessness, ruin, waste.

The fishermen understand that a government that promised freedom is now taking the remnants of it away

‘Do you eat fish?’ Bill asks me, curiously. I like white fish, I tell him. ‘I like fishing for Dover Sole,’ he says. ‘They always hold their price – £25 a kilo. Once you skin them, they are so sweet, they’re lovely. Don’t have to burn a lot of oil to get there, at most half a mile.’ He points west, towards Lamorna. The fishermen, he says, are ‘the last of the hunters. The things you see, particularly in the early morning! Fish rashing, dolphins feeding on the fish that are rashing, the sunrise, the western shore: passing the cliffs at Porthcurno Cove with the sun on them, what a commute to work. Yeah, the best – every day is different, every catch is different.’ He says he went out in a group of four boats recently. ‘All four [men] had open heart surgery and all of us chasing the mackerel towards the Lizard. There must be something about this job that keeps us going. Now they are trying to stop all that.’ Twenty years ago, there were 20 boats fishing out of Mousehole. In 20 years, he thinks there will be none.

So this is a war on small boats, a race towards generic and unhappy lives. Who will save the small boats? Not the big boats, who are pleased to lose the competition. Not government, who legislate like men who have never been in a boat. For small boat fishermen, who overwhelmingly voted for Brexit, this is the final insult. They were promised so much: a Brexit boom, and the trumpet call of freedom. Instead, they got more over-regulation than Ireland, and this.

A few weeks ago, I get a message from Bill. He failed the medical. I ring him, and he sounds resigned, but he’s a Cornishman. This is a duchy that increasingly exists for others. There’s not much left to strip away.

The Spectator’s 2023 Christmas quiz

Fairly odd

1. What had for 50 years been the name for Fanta Pineapple & Grapefruit before it was changed this year?

2. Why did the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Revd Justin Welby, have to pay £510 in fines and costs?

3. Which country overtook France as the biggest buyer of Scotch whisky, despite imposing an 150 per cent import tariff?

4. For whose visit did Papua New Guinea declare a public holiday, only to find he decided instead to fly straight home from the G7 summit in Japan?

5. Which parents named their new son Frank Alfred Odysseus?

6. In which country were six children and two adults rescued by helicopter and zipwire after hours stuck in a cable car dangling 900ft in the air?

7. Opposition leader Patrick Herminie was charged with witchcraft in which country?

8. Name the founder of the Inkatha Freedom party, who died this year aged 95 and had played the role of his great-grandfather Cetshwayo in the film Zulu.

9. A factory in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, was fined $14,500 after two workers had to be rescued from a vat of what?

10. President Luis Lacalle Pou of Uruguay changed his mind about recasting as a dove of peace the seven hundredweight bronze eagle figurehead from which ship?

You don’t say

In 2023 who said:

1. ‘I am not alone in thinking that there is a witch hunt under way, to take revenge for Brexit and ultimately to reverse the 2016 referendum result.’

2. ‘The documents, the whole thing is a witch hunt. It’s a disgrace.’

3. ‘Rachel Reeves is a serious economist.’

4. On the death of Silvio Berlusconi: ‘I have always sincerely admired his wisdom, his ability to make balanced, far-sighted decisions.’

5. ‘I had known Prigozhin for a very long time, since the start of the 1990s. He was a man with a difficult fate, and he made serious mistakes in life.’

6. ‘The bonfire of EU legislation, swerved. The Windsor framework agreement, a dead duck, brought into existence by shady promises.’

7. ‘I suspect that the new member for Mid Beds may actually support me a little more than the last one.’

8. ‘There is no good reason why we can’t train up enough HGV drivers, butchers or fruit pickers.’

9. ‘And I know she’s up there, fondly keeping an eye on us. She would be a proud mother.’

10. ‘I’d like to apologise for my choice language. That was unnecessary.’

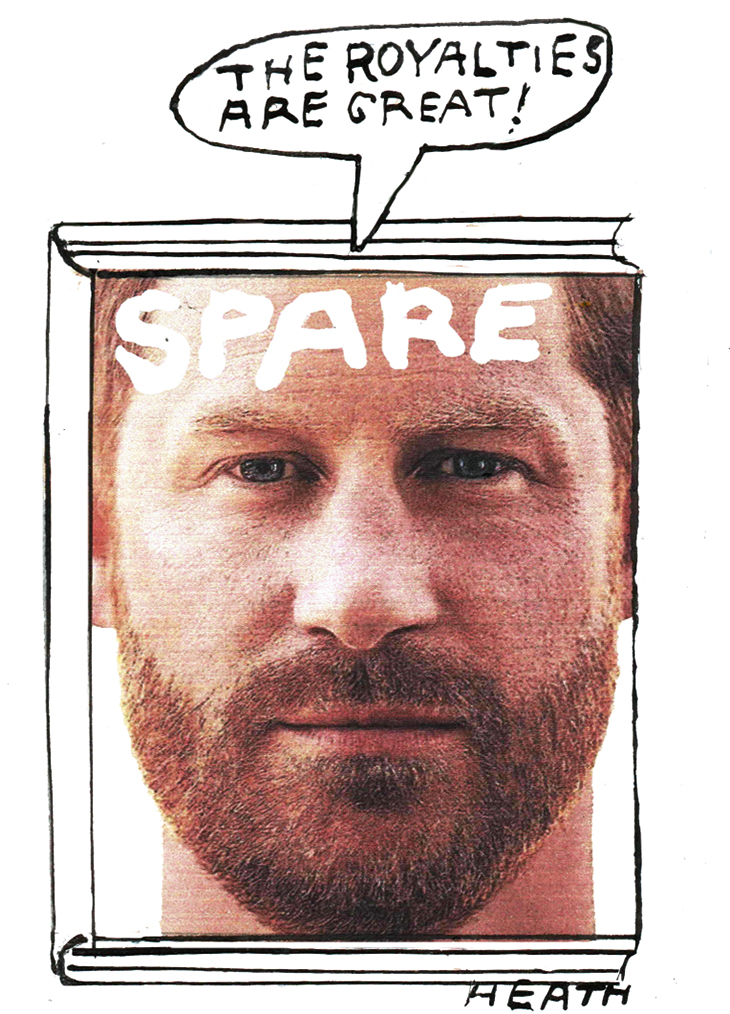

Royal icing

1. At what outdoor event did the King wear a kilt of a new tartan, registered with the Scottish Register of Tartans?

2. Name the book published in 2023 in which the Duke of Sussex said that his brother ‘grabbed me by the collar, ripping my necklace, and he knocked me to the floor. I landed on the dog’s bowl, which cracked under my back, the pieces cutting into me’.

3. Who was made Duke of Edinburgh?

4. The crown with which Queen Camilla was crowned had been used for the coronation of which previous queen consort?

5. At the coronation procession from Westminster Abbey to Buckingham Palace, which member of the royal family rode in the capacity of Gold Stick in Waiting in the uniform of a colonel of the Blues and Royals, with the Garter sash and a bicorn hat with red plume?

6. Bees feature on the new £1 coin of Charles III. What fish is depicted on the 50p?

7. In the white drawing room at Windsor Castle in July, to whom did the King show a letter from Queen Elizabeth II in 1960 to President Eisenhower, including a recipe for the drop scones he had enjoyed at Balmoral?

8. The Prince and Princes of Wales visited Moray and Inverness in November under what ducal titles?

9. During a state visit to which country did the King say: ‘Ni furaha yangu kuwa na nyinyi jioni ya leo’ (‘It is my great privilege to be with you this evening’)?

10. To which country was the state visit of the King and Queen postponed because of violent protests against the raising of the pension age from 62 to 64?

Call me al

Translate these abbreviations and give the full Latin versions:

1. Et al

2. e.g.

3. i.e.

4. AD

5. p.m.

6. Viz

7. Ibid

8. Op cit

9. Q.E.D.

10. q.v.

Farewells

1. What name did Ronald Blythe, who died in 2023 aged 100, give to the Suffolk village of which he published a portrait in 1969?

2. Who died aged 93, having served from 1992 to 2000 as the only woman Speaker of the House of Commons so far?

3. Name the Downing Street press secretary, 1979-90, under Margaret Thatcher’s administrations, who died aged 90.

4. What was the name of the jazz clarinettist and cartoonist ‘Trog’, creator of the Flook strip, who died aged 98?

5. Who was known for the Private Eye comic strip Barry McKenzie (with Nicholas Garland) and for his stage character Dame Edna Everage, and died aged 89?

6. Which cartoonist produced the strips called The Cloggies and The Fosdyke Saga and died aged 89?

7. Which Harlem-born singer won fame with ‘The Banana Boat Song’ in 1956 and died aged 96?

8. Name the singer who had a hit with ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco’ and died aged 96.

9. Who died in 2023 aged 94, after editing the New Statesman from 1965 to 1970 and writing a column in The Spectator from 1981 to 2009?

10. Name the Low Life columnist of The Spectator since 2001, who died aged 66, and wrote in 2005: ‘My friends told me thathalfway through the ball they’d gone to look for me and found me unconscious outside, flat on my face on the lawn, next to the naked girl. Someone had taken off my shoes, arranged them neatly side by side and set fire to them.’

’Tis the season

Match the writers to the passages below: Jane Austen, Henry James, E.F. Benson, Anthony Trollope, Evelyn Waugh, Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, E.Oe. Somerville and Martin Ross, Saki, Thomas Love Peacock.

1. Christmas Day dawned, a stormy morning with a strong gale from the south-west, and on Elizabeth’s breakfast-table was a pile of letters, which she tore open. Most of them were threepenny Christmas cards, a sixpenny from Susan, smelling of musk, and none from Lucia or Georgie. She had anticipated that, and it was pleasant to think that she had put back into the threepenny tray the one she had selected for him.

2. ‘At Christmas every body invites their friends about them, and people think little of even the worst weather. I was snowed up at a friend’s house once for a week. Nothing could be pleasanter.’

3. ‘Mummy, do look at Rex’s Christmas present.’ It was a small tortoise with Julia’s initials set in diamonds in the living shell, and this slightly obscene object, now slipping impotently on the polished boards, now striding across the card-table, now lumbering over a rug, now withdrawn at a touch, now stretching its neck and swaying its withered, antediluvian head, became a memorable part of the evening, one of those needle-hooks of experience which catch the attention when larger matters are at stake.

4. ‘You can’t have the carriage to go about here. Indeed, I never have a pair of horses till after Christmas. I hope you know that I’m as poor as Job.’

‘I didn’t know.’

‘I am, then. You’ll get nothing beyond wholesome food with me. And I’m not sure it is wholesome always. The butchers are scoundrels, and the bakers are worse.’

5. Mrs Knox’s donkey-chair had been placed in a commanding position at the top of the room, and she made her way slowly to it, shaking hands with all varieties of tenants and saying right things without showing any symptom of that flustered boredom that I have myself exhibited when I went round the men’s messes on Christmas Day.

6. He had no natural avidity and even no special wrath; he had none that had not been taught him, and it was doing his best to learn the lesson that had made him so sick. He had his delicacies, but he hid them away like presents before Christmas.

7. Four of the chosen guests had, from different parts of the metropolis, ensconced themselves in the four corners of the Holyhead mail. These four persons were, Mr Foster, the perfectibilian; Mr Escot, the deteriorationist; Mr Jenkison, the statu-quo-ite; and the Reverend Doctor Gaster, who, though of course neither a philosopher nor a man of taste, had so won on the Squire’s fancy, by a learned dissertation on the art of stuffing a turkey, that he concluded no Christmas party would be complete without him.

8. The turkey in the poultry-yard, always troubled with a class-grievance (probably Christmas), may be reminiscent of that summer morning wrongfully taken from him when he got into the lane among the felled trees, where there was a barn and barley.

9. He might so easily have married some pretty helpless little woman, and lived at Notting Hill Gate, and been the father of a long string of pale, clever useless children, who would have had birthdays and the sort of illnesses that one is expected to send grapes to, and who would have painted fatuous objects in a South Kensington manner as Christmas offerings to an aunt whose cubic space for lumber was limited.

10. The distance from the station was considerable; the messenger had been ‘keeping Christmas’ in more than one beer-shop on his way to the house; and the delivery of the telegram had been delayed for some hours. It was addressed to Natalie. She opened it – looked at it – dropped it – and stood speechless; her lips parted in horror.

Click here for the answers

The dying art of thank-you letters

‘Still no word of thanks. No letter, no email, no text. No acknowledgement that it even arrived. Did it arrive? Did I post it to the wrong postcode? Did I tap in the wrong account number? Of course it arrived. He just can’t be bothered to thank me. Such bad manners! I blame his mother for not bringing him up properly.’

These are the insomniac thoughts of the older generation as they try to come to terms with the younger generation’s bewildering non-thanking habit. The silence of early January, the non-landing of letters from grandchildren and godchildren on the mat, the non-pinging of affectionate emails of gratitude, really pains them, brought up as they were on the belief that writing thank-you letters is good manners, and good manners mean everything.

As soon as parental control loosens, thank-you letter writing goes the way of shoe polishing and toenail cutting

I asked a cohort of grandparents and godparents in their sixties, seventies and eighties about their experiences of the younger generation’s etiquette of thanking, and the response was overwhelmingly along the lines of: ‘I’m grateful these days if I get any written thanks from my grandchildren or godchildren in any form. It certainly doesn’t need to be a handwritten letter.’ ‘They don’t, on the whole, register thanks. This I lament,’ said one. ‘Rare to get any response at all, even for quite large 21st-birthday cheques,’ said another. ‘Astonishing how godchildren don’t thank.’ ‘I think our elder lot of grandchildren (when still under parental control) were the last children in England to write thank-you letters for Christmas presents.’ These people have learned to be pathetically grateful for any crumb of acknowledgement from the young darlings, who might have bothered to move their thumbs enough to tap the text: ‘Thanks for the lovely present, I really look forward to spending it xx.’

Gone, it seems, are the days of agonised New Year’s Day pen-sucking, when those of us brought up in the 20th century had to sit in front of a blank sheet of headed writing paper, trying to think of something nice to say about the masonry drill or the cassette case, whether we liked them or not, and remembering the rules: never begin with the words ‘thank you’ (too predictable); always go on to the second side; at the very least, express thanks and add ‘one other piece of news’; always use a first-class stamp. It was never fun, but for those half-hours we were actively thinking of the giver, forcing ourselves to dream up words and information they might be gratified to hear.

Today’s under-12s are still under parental control enough to put up with this annual agony, but the habit and sense of duty clearly aren’t being drilled into them brutally enough, because as soon as parental control loosens, thank-you letter writing goes the way of shoe polishing and toenail cutting.

One respondent said to me: ‘This year I’ve decided I’m not giving presents to any godchild who didn’t thank me last year. I have six godchildren and am only sending one present this year.’ That’s the sanction the older generation has up its sleeve: withdrawal of beneficence. Does such a drastic measure serve the non-thankers right? I asked the question to The Spectator’s Dear Mary, Mary Killen, herself an assiduous writer of thank-you cards and emails. She said she’d recently met a man who’d told her that his godson had sent him a text just saying ‘Thnx’, after he’d got him a job. ‘Which effectively means he won’t be helping him again.’

‘It hasn’t sunk into the young, who are in other ways really nice people,’ said Mary, ‘that in the generation above them, who hold all the money and the power, it is a real black mark not to write and thank for things. By not thanking, they are micro-spoiling the life of the benefactor by leaving them in a void of waiting. Just as young people crave “likes” on Instagram, the older generation want feedback and endorsement if they have given a present or party, so if they hear nothing at all, it’s a bit of a micro-aggression.’

Perhaps the effect of written thanks has been so debased by the endless corporate thanks pouring into our phones (‘Thank you for being our valued customer’, ‘Thank you for choosing us. Please let us know how we did’) that people in their twenties have no craving for the word ‘thank you’, and see no reason why anyone else would. Not that some of them don’t write marvellous thank-you emails; I’ve been shown a few, by friends who have recently received them, and the best ones are brimming with liveliness and gratitude. Emails do seem to flow better than letters; one older man I asked said he actively preferred thank-you emails as they were ‘immediate and full of the life of the party’, while letters could be more stale and stilted. The downside to thank-you emails, though, is that they demand a response: a thanks for the thanks, whereas with a handwritten letter, the case is closed.

The tradition of thank-you letter writing is still very much alive among the over–sixties, some of whom write ‘by return of post’ and listen to the alarming sound of their thank-you letter falling into the bottom of the almost-empty pillar box, signalling the dying of the art. Nicholas Coleridge, one of the most punctilious thankers I know, tells me: ‘My normal practice is to write all thank-you letters the next morning and post them in the so-called priority postbox. A handwritten thank you should be one and a half to two sides, and should show evidence of paying attention by referencing actual conversation, jokes, activities or anecdotes from the evening or weekend. Sometimes we receive thank-you letters from friends of our children which begin, “Thank you for inviting me to stay for the Bank Holiday at your house Wolverton Hall near Pershore in Worcestershire”, like a police witness statement.’

The arbiter of taste Nicky Haslam agrees. ‘We storytellers want a story, or even a drawing. It’s not enough to say “thank you for a lovely evening”. An email is fine, as long as there’s something specific and funny in it.’

‘And your godchildren?’ I asked him. ‘Do they write to thank you for presents?’

‘I don’t think they know how to write,’ he said. ‘And they’re all much too busy getting divorced.’

Why are quotes so often misattributed?

‘Macmillan,’ said my husband with rare succinctness. Someone on the wireless had just asked who it was who said: ‘Events, dear boy.’ I agreed with my husband, as in moments of weakness I do. But what is the source of the quotation?

The first rule is that most common quotations were not said by the people to whom they are attributed. The second rule is like unto it: a few big names – Winston Churchill, Oscar Wilde – attract quotations as magnets attract iron-filings.

So, talking of iron, Churchill’s phrase the iron curtain had been used before him. It secured attention, though, when he used it in a speech at Fulton, Missouri, in 1946: ‘From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.’

Someone found that the phrase had been used by Vasily Rozanov in 1918 in his book The Apocalypse of Our Times: ‘An iron curtain is being lowered, creaking and squeaking, at the end of Russian history.’ I can’t say I knew anything about Rozanov and I have no intention of reading that book.

His metaphor came from the theatre. In 1794, the Morning Post had reported that the new Drury Lane Theatre had ‘an iron curtain, which extends to the walls, and is so calculated as completely to prevent the flames spreading to the front of the House, though the scenes were to catch fire’. The theatre burnt down on 24 February 1809.

It was then that Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the owner of the theatre, as he sat in the Piazza Coffee House near the burning building, was reputed to have responded to remarks about his philosophical calmness: ‘A man may surely be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside.’

Or did he say that? Thomas Moore reported it in his Memoirs of Sheridan but ‘without vouching for the authenticity’ of the anecdote, which, he conceded, might have been ‘attendant upon all fires, since the time of Hierocles’, a philosopher of Alexandria, who could have been expected to know about the fire that destroyed the library there, although revisionist history doubts even that happened.

Rozanov brought the iron curtain down on ‘the end of history’, itself a phrase incorporated by Francis Fukuyama into the title of a book in 1992. In 1920, Ethel Snowden had seen the curtain differently in her Through Bolshevik Russia: ‘We were behind the “iron curtain” at last!’ The outspoken wife of Philip Snowden, later a Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, she had called for state control of marriage, believing that the mentally ill and anyone under 26 should not be able to marry. Yet she was not an utter idiot, observing: ‘I know everybody I met in Russia outside the Communist party goes in terror of his liberty or his life.’

In 1945, a year before Churchill, Sir Thomas St Vincent Troubridge (from a line of naval baronets, though he spent his last decade as Examiner of Plays in the Lord Chamberlain’s Office) declared that ‘an iron curtain of silence has descended, cutting off the Russian zone from the western Allies’. Even Goebbels used the phrase, for heaven’s sake, in 1945, in the magazine Das Reich. But when we hear the words iron curtain, we do not, fortunately, think of Goebbels. Iron curtain is consciously associated with Churchill and not wrongly.

And as almost every writer of letters to the newspapers knows, Voltaire said: ‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.’ He did not say it, though.

The words were first published in 1907 in a book by S.G. Tallentyre, or so the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations says. But there was no such person as S.G. Tallentyre, for that was a mere pen-name of a writer called Evelyn Beatrice Hall. In a letter in 1939 to Modern Language Notes, she made it clear that the words were hers, and she wasn’t pretending they were Voltaire’s. It did no good. No one ever writes: ‘In the words of Evelyn Beatrice Hall, “I disapprove of what you say…”.’

As for Macmillan, no definite source has been found. No one knows to whom he said it or when. ‘Events, dear boy’ sounds like him. More than 20 years ago Robert Harris called the phrase ‘infuriatingly ubiquitous’ and there has been no let-up since. The infuriation persists, everywhere.

My sporting questions for 2024

Could this be the year when England’s men win their first international football trophy for 58 years? After all, they have the best striker in Europe in Harry Kane and the best attacking midfielder in Jude Bellingham, both of whom are being treated like Wellington and Nelson at their respective clubs BayernMunich and Real Madrid. This should be about time too that pundits admit that the way Bellingham lit up the European Championships in Germany makes him, at the very least, Bobby Charlton’s equal. If he is not Sports Personality of the Year in 2024, something very odd must have happened in the space-time continuum.

If Bellingham is not Sports Personality of the Year in 2024, something very odd must have happened

England also have the best right winger in Europe in Bukayo Saka; a superb holding midfielder in Declan Rice; and the fastest full back on the planet in Kyle Walker. So can anything stop England? Well yes, and his name is Harry Maguire.

The Championships will be superbly organised, as the man in charge is Philipp Lahm, one of the smartest, most creative players ever to grace a football field. But might the game come to its senses and stop awarding career-ending penalties because, after six minutes studying the videotape, the VAR decides that the ball has brushed someone’s fingernail? Goals should be hard to score and we should be able to celebrate them.

In tennis, 2024 could be the year when we finally learn whether Emma Raducanu has buckled under the weight of expectation she piled on herself by winning the US Open as a teenager – and wringing out of it as much publicity and moolah as she could – and will be forever remembered as a one-hit wonder. Or could she start winning again?

And can anyone stop Novak Djokovic? Rivals come and then mostly go again. Nole won three out of four Grand Slams this year, and next year he has got the Olympics as well, so he seems unlikely to be dialling anything down. Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz pop up occasionally to give him a scare, as do Daniil Medvedev, Stefanos Tsitsipas and Andrey Rublev. Even so, their only real hope will be that the hardened Serb boycotts all tournaments because of a ‘lack of respect’.

At the risk of tempting fate, will the 2024 Paris Olympics be a triumph of French chic? Or will the staging of the Games in a city with a rich history of street unrest become a focus for those who want to spoil our fun? The signs aren’t good, but then Parisians like to bellyache about everything. Fares will be doubling, there are unfathomably complex security arrangements at the venues, and most of the city’s citizens now disapprove of the whole shebang. My guess, though, is that it will almost certainly be a triumph, just like London 2012 – remember that?

As for cricket, will Jimmy Anderson finally retire? Or, when England announce their Test squad for Afghanistan in 2038, will we find out he’s being ‘rested’? This could also be the year when either Ben Stokes admits defeat in his battle against injury or English cricket gives thanks to a knee surgeon for resurrecting the Test career of a man whose style of inspirational leadership was so lacking in the 2023 World Cup.

As English rugby labours in a morass of largely self-inflicted problems, the big question is whether captain Owen Farrell’s sabbatical will make much difference. In 2024’s Six Nations, England should beat Italy and Wales, have a tight match with Scotland, and get stuffed by France and Ireland. And yet… Ireland might be going over the hill, and France will lack Antoine Dupont. The important thing for England will be to make sure Marcus Smith and Henry Arundell are on the pitch as much as possible. At 5-1, they feel quite a tasty bet.

Meanwhile, could Formula 1 get any more dislikeable? Its insistence that it is first and foremost a ‘lifestyle brand’ will doubtless lead to an announcement that it is hosting a Grand Prix which doesn’t involve any actual motor racing. Max Verstappen is declared the winner. No one notices.