-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Wagner rewilded: Das Rheingold, at the Royal Opera House, reviewed

In Northern Ireland Opera’s new Tosca, the curtain rises on a big concrete dish from which a pair of eyes gaze down, impassive. Walls of scaffolding tower on three sides of the stage, creaking as they expand under the heat of the stage lights. Point taken: Cameron Menzies’s production (the sets are by Niall McKeever) is a semi-abstract updating. It’s a fairly standard contemporary approach to Puccini’s Napoleonic thriller, though whether you get the full impact that comes with a more period-specific setting – that sense of individuals being crushed beneath the wheels of history – is another question.

When you live on your raw theatrical instincts, you walk a treacherous path between sniggers and the sublime

Anyway, that’s just how things are now and regular operagoers will be used to decoding the various surreal anachronisms that arise whenever a director sets out to cobble together a synthetic reality. Menzies does generate a potent atmosphere of entrapment and menace, and it’s a pity that he blunts the opera’s ending, with Cavaradossi picked off by cloaked figures on top of a sort of gantry, and Tosca throwing herself down the same flight of stairs that we’ve just seen Cavaradossi ascend. Sure, that’s got to hurt, but it doesn’t exactly look terminal.

Still, Tosca is a big exciting opera and this – the largest production in the company’s history – was a big exciting occasion, especially once the audience started to warm up. Cavaradossi was played by Peter Auty, a singer whose many fine qualities don’t really include sensuality. That gave a certain vulnerability to his big arias: the artist as boyish idealist, trapped between the more dangerous impulses of Tosca (Svetlana Kasyan) and Scarpia (Brendan Collins). With his knee-breeches and pervy facial hair, Collins made a plausible predator, singing with insinuating lyricism and a tone like black velvet. ‘Agile as a leopard’ is his drooling description of Tosca, and Kasyan was just that. Vocally, she could blaze, but she could also snarl and purr. She was proud, she was impulsive and she dispatched Scarpia without even removing her headdress.

Menzies might have done more to stoke the fires between this central trio: he was a little too ready to let them stand there waving their arms about. Against that, there were gutsy choral scenes plus the Ulster Orchestra sounding alert and alive under Eduardo Strausser, a conductor who clearly knows how to make this score sing. Grand Opera House is what it says on the front of the theatre, and grand opera is exactly what you get here. While the Arts Council pursues its vendetta against opera in England, it’s inspiring to see such unabashed ambition on the other side of the Irish Sea.

By the opening night of Das Rheingold at the Royal Opera (the first instalment of a new Ring cycle directed by Barrie Kosky) it felt as though a triumph had been pre-ordained, with Twitter (sorry, ‘X’) abuzz with excited leaks from the dress rehearsal. Despite that, it was compelling. Designer Rufus Didwiszus provides a single, multi-purpose set: a huge fallen and fossilised tree, from which the Rheingold gloops and spurts in a gooey hormonal discharge. Erda is on stage throughout – a shuffling, stark-naked crone, evoking unfortunate memories of the pratfalling, slow-moving granny in Cal McCrystal’s recent G&S productions.

Too bad. That’s the risk you take when, like Kosky, you live on your raw theatrical instincts; walking a treacherous path between sniggers and the sublime. But Kosky (unlike Richard Jones in his recent ENO staging) seems genuinely curious about Wagner’s intentions: he’s out to tell a story rather than cut Wagner to size. A simple spotlight and a revolve are used to suggest different layers of time. Why does Kosky drop the curtain between scenes, throwing the emphasis back on to the music, when Wagner designed a whole theatre specifically to make the orchestra an unseen, near-magical presence? Possibly he’d say that since Wagner’s time, film and TV have drained the all-pervading orchestral soundtrack of any remaining enchantment. This way, we’re made to listen, and to be aware that we’re listening. Wagner is being rewilded.

Das Rheingold is only a prologue, and Kosky presents his central characters, suitably enough, as overgrown adolescents, with Alberich (Christopher Purves) finding self-awareness after a sexually degrading debagging by the Rhinemaidens. The parallels with the equally bullet-headed Wotan (Christopher Maltman) are striking; both are vocally magnificent and perceptive in their characterisation. The gods, meanwhile, are a bunch of horsey Eurotrash arrivistes from the German edition of Hello!. By the end, Maltman is already recoiling from them, ageing visibly as he begins his long journey into self-annihilation. Loge (Sean Panikkar) dances around, cackling madly; his tenor coiling, flickering and flashing over the orchestra (Pappano sounded noticeably more animated, and sure-footed, than in his last London Ring cycle). Operas aren’t TV series – we’ve a long wait now until Die Walküre – but after this Rheingold I’d gladly have binged all night.

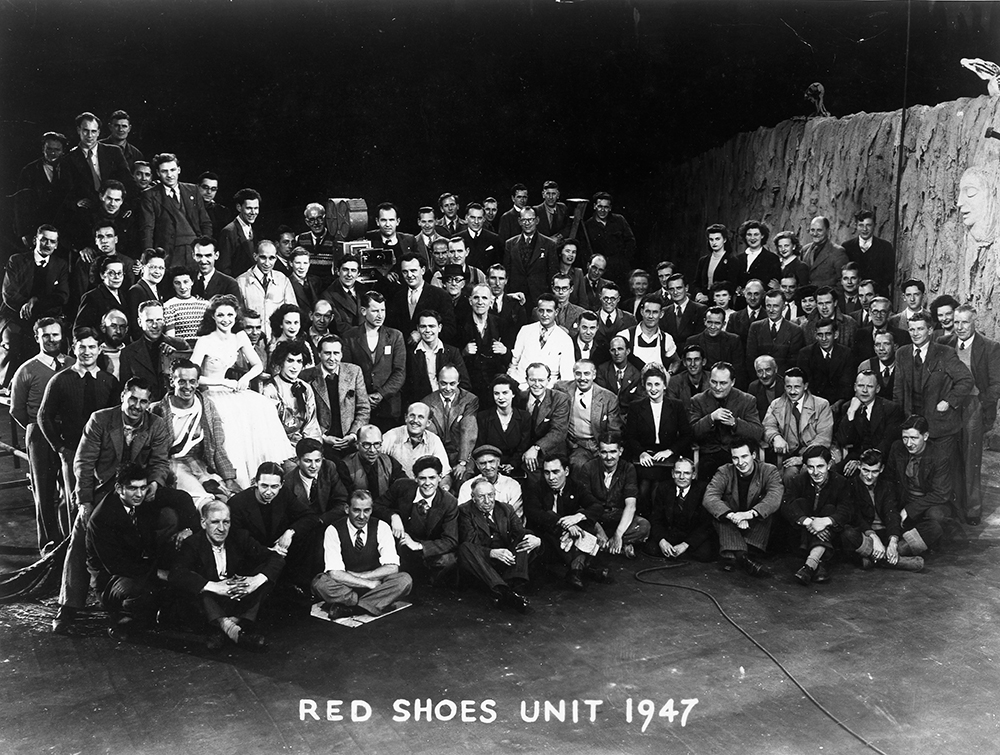

The dazzling classic The Red Shoes has several unfashionable lessons for us today

The Red Shoes, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film about a ballet and its company, is 75 this month, and its birthday is being marked with great fanfare. From October to December, the BFI is putting on a major retrospective of the films of Powell and Pressburger, with an accompanying exhibition and nationwide screenings of The Red Shoes itself. A companion book to The Red Shoes by Pamela Hutchinson – stuffed with insight and background – is being published, as well as a lavish volume, The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger, complete with pictures and essays (almost love letters) about the late filmmakers from artists such as Tilda Swinton and director Joanna Hogg.

For Martin Scorsese it was ‘film as music’, ‘the movie that plays in my heart’

Powell and Pressburger named their production company The Archers. And they hit the bullseye with an extraordinary number of films: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951). Six of their movies feature in the Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, a number matched only by Hitchcock. But where does The Red Shoes sit in the cinematic pantheon? At its first studio screening, executives from Rank were baffled and even appalled, dismissing it as an ‘art movie’ and giving it, initially, a strictly limited release. Kenneth Tynan spoke of its ‘costly and inelegant vulgarity’. Others, like the great film critic Dilys Powell, noted its dazzling experimentalism. For Martin Scorsese it was ‘film as music’, ‘the movie that plays in my heart’. In lists of the most-admired British movies, it nearly always comes in the top ten. Rank and Tynan, you can conclude, perhaps got it wrong.

The two stories The Red Shoes tells have a myth-like clarity. First there is the ballet itself, based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale about a girl who, enraptured by a pair of red shoes, makes the mistake of putting them on, only to find they have a frenzied life of their own. The shoes dance her in an unstoppable whirl to an exhaustion (and isolation) so profound she chooses to chop off her feet (and will later die) rather than give in to the delirium.

The second, outer story is of a modern, international ballet company, and a young dancer Vicky Page (Moira Shearer), plucked from corps-de-ballet obscurity to wear the Red Shoes by impresario Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), the charismatic but tyrannical director of the company who vows to make her ‘the greatest dancer the world has ever known’. But personal life intervenes in the shape of young ballet-composer Julian Craster (an over-ripe Marius Goring) whose destiny is inseparable from her own. Their love affair and marriage provoke a rage worthy of Greek gods in the jealous Lermontov, for whom anything but dedication to art is a betrayal. ‘The dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer,’ he hisses. Neither Julian, Lermontov nor the Red Shoes will let Vicky go.

Seventy-five years on, The Red Shoes’s magic is undimmed. It feels less quaint or dusty than many films half its age, and nearly all the Archers’ arrows hit home. Designed by the painter Hein Heckroth, it has a Matisse-like gorgeousness of colour and a soundtrack, by Brian Easdale, as far from the usual rum-ti-tum bombast of 1940s film scores as can be imagined. Life in it, you feel, is just as it should be. Covent Garden is still a fruit and vegetable market, the French Riviera (to which the ballet company decamps) looks as crisp as an art-deco tourist poster, and the artistes – in bracing hierarchy – are still summoned to work by hand-written memos (in English, French and Russian) pinned to the company noticeboard.

Today Lermontov would have been dismissed long ago for bullying, micro-aggressions and high-handedness

Yet what makes it so unfashionable – and thus so timely – is its depiction of Art with a capital ‘A’, and the supremacy of the demands Art makes on creators. Powell himself was explicit about this, describing the film as ‘a haunting, insolent picture, in the way it takes for granted that nothing matters but art, and that art is something worth dying for’. The Red Shoes, he said, was intended to be ‘a gathering together of my whole accumulated knowledge of the film medium – disciplined by music, enhanced by colour, with the very maximum of physical action’. It’s not only Powell’s ‘accumulated knowledge’ we get. In few films do you find such a sense of collaboration, of experts in their field – dance, visual art, costume, cinematography – working together so inventively at the top of their game.

In the 1990s, when I first saw the film, Michael Powell had recently died and there were several documentaries about him on television. They told of his struggles to get The Red Shoes made, his battles with Rank executives to get the right artists working for him, his refusal to compromise over the 17-minute modern-dress ballet he knew The Red Shoes needed at its centre. The NFT used to show it regularly, and you would come out of the cinema – straight from the catharsis of its ending – to walk along the South Bank in a dream. The film held out the possibility of a life dedicated to your craft, full of travel, love, sacrifice and passionate allegiances. Hutchinson, in her penetrating book, calls it (correctly) ‘a dangerous film to see at an impressionable age’, but it remains a young person’s movie nonetheless – one that chimes most strongly when your ideals are unsullied and your future, like the Red Shoes, appears to you in Technicolor.

Seeing it in 2023, it still thrills with its magic but is different and sadder, more a warning than a promise. Vicky, poised for flight, seems doomed from the outset. Lermontov appears less a real person and more like Art itself, mercilessly trashing its practitioners should they fall short of its demands. Only for Powell, with his sense of creative martyrdom, did this dark, tragic fairy tale seem to have a happy ending.

Would anyone die for art in 2023? Amid newly sanitised classics, quota-castings, politically driven awards, formulaically ‘progressive’ narratives and ‘stay in your lane’ restrictions, it seems doubtful many would fight for it at all. The ideals of The Red Shoes – ones to build a life on – seem to have been betrayed and dismantled by their very gatekeepers. One imagines Powell and Pressburger surveying the modern world and clutching their heads in shock.

It’s fascinating to compare it with last year’s Tár, Todd Field’s bonfire of the artist’s vanities, perhaps so essential to their creating anything at all. As for Lermontov, he would have been dismissed long ago for bullying, micro-aggressions and high-handedness. His stern prioritising of Art would seem unreasonable, elitist and a red rag to the #BeKind brigade. Whether this is a price worth paying for the new orthodoxy is up to viewers to judge. The clash of values in The Red Shoes leaves us with a dancerless ballet and a gutted work of art, its heart torn out but still staggering on regardless. Something for us to ponder this autumn, as we make our way along the South Bank and beyond.

‘Environmental vandalism’: Sunak’s net zero u-turn sparks fury

Rishi Sunak hasn’t even formally announced his plans to water down the government’s net zero pledges, but already the backlash has begun. Tory peer Zac Goldsmith, who stormed out of Sunak’s government this summer, described the u-turn as a ‘moment of shame’ for Britain. He called for an ‘election now’ and said the PM’s time in office will be remembered ‘as the moment the UK turned its back on the world and on future generations’.

Labour’s Ed Miliband accused the PM of being ‘rattled’ and ‘out of his depth’ after it emerged the PM was considering postponing a ban on petrol cars and gas boilers. Miliband said the Tories have ‘failed on the climate crisis.’

Predictably enough, Green MP Caroline Lucas is also livid. She accused the government of being ‘economically illiterate’.

‘It is a prime example of environmental vandalism,’ she told the BBC, adding that:

‘The UK has a historic responsibility to go further and faster than many other countries because we were the first country into the Industrial Revolution. That means we have done more to put fossil fuels into the atmosphere’.

Some Tory MPs are also furious. Simon Clarke, no friend of Sunak’s, said his Red Wall consitutents approved of the push for net zero. He said:

‘When the history of this period of Conservatives government is written, our leadership on climate issues will be one of our main achievements…How does it benefit either our country or our party to shatter it?’

Tory MP and Cop president Alok Sharma also criticised Sunak. ‘For any party to resile from this agenda will not help economically or electorally,’ he wrote.

Is Sunak willing to withstand the backlash?

The flaw in Rishi Sunak’s plan to water down net zero

Rishi Sunak will reportedly make a speech later this week watering down some of the targets the government has set itself on achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050, although that target itself will not be touched).

The proposed ban on new petrol and diesel cars will be put back by five years to 2035, which would bring Britain in line with the EU. The ban on new oil-fired boilers will be put back from 2026 to 2035, thus relieving the Conservatives of the prospect of mass grumbling in one of their natural constituencies, rural areas. Even in 2035, it seems, the target will be to reduce installations only by 80 per cent, in recognition than many homes are difficult to bring up to the insulation standards required for heat pumps to work effectively. The same principle will apparently be applied to gas boilers, new installations of which were previously on line to be banned entirely from 2035.

Tory MP Chris Skidmore, who piloted the net zero target through the Commons in 2019, is outraged

In addition, the Prime Minister is expected to announce that there will be no new taxes to discourage flying, and that recycling schemes involving multiple bins and other receptacles will fall out of favour. Requirements for rented houses to achieve standards on Energy Performance Certificate Ratings will also be relaxed – landlords had been threatened with large fines if they failed to comply.

Tory MP Chris Skidmore, who piloted the net zero target through the Commons in 2019, is outraged. He told the BBC that Sunak’s watering down of commitments will ‘cost the UK jobs, inward investment and future economic growth that could have been ours by committing to the industries of the future’.

Sceptics might respond by asking: where are all the ‘green jobs’ that we were promised when the Climate Change Act was first passed in 2008 – and again when the net zero target was set in 2019? ONS figures show insipid growth in jobs in the ‘low carbon economy’ since 2015. As many people have noted, Britain for example has become a world leader in the installation of offshore wind turbines, yet that hasn’t brought huge numbers of jobs to Britain – most of the kit is made elsewhere, especially in China where the cost of energy (thanks, in part, to the lack of a legally-binding net zero target) is much lower.

What is plain, however, is that as things currently stand, the costs of net zero will fall disproportionately upon the less well off – such as people who have stretched every last sinew to afford the mortgage on a drafty 19th century home and who have been threatened with a bill for £20,000 or more to improve insulation and fit a heat pump. Or motorists at the lower end of income scale who are already finding cars they can afford, such as the Ford Fiesta, withdrawn from the market as manufacturers scramble to electrify their ranges.

If Sunak can provide some reassurance to such voters, he may have a chance of retaining some former ‘red wall’ seats. But there is a big hole in his plans. If, as he is expected to say, he remains committed to his target for net zero by 2050, how does he expect to get there, given than he is apparently ditching many of the targets along the way? It might well be the right thing, for example, to water down targets on electric cars and heat pumps, but the truth is that even those aims were unlikely to be even nearly enough to eliminate net carbon emissions by 2050. Without them, the 2050 target becomes an even larger pie in the sky.

In an apparent dig at Boris Johnson, Sunak is expected to say that previous governments have ‘taken the easy way out’ on net zero, ‘saying we can have it all’. It is certainly true that Johnson’s assertion we could reach net zero and enrich ourselves at the same time, with no negative effect on our living standards’, was his most blatant example of ‘cakeism’. But so long as he sticks to the 2050 target, while watering down the means by which we were supposed to get there, Sunak will not be any closer to reality.

Why is France so fascinated by the royals?

As King Charles’ state visit to France begins, it is clear that France is not as republican as it claims. The death of Queen Elizabeth II in September 2022 gave way to an outpouring of French national grief. Speaking for his people, President Emmanuel Macron tweeted: ‘Her death leaves us with a sense of emptiness’. On 19 September, seven million viewers watched the state funeral live on six French television channels, an audience share of 66.7 per cent.

One might of course say that it was Queen Elizabeth’s exceptional qualities as a human being, her unfailing devotion to duty, that were being acknowledged rather than her status as monarch. Yet French audience figures for Prince Philip’s funeral in April 2021 were also seven million and for Princess Diana in 1997 it was ten million.

In this popularity, there is a French wistfulness for a regime other than the present republican system

At the heart of this is a French fascination with royalty in general, and British royalty in particular. On the eve of Charles’s coronation in May, according to the French travel search engine Expedia.fr, searches for London hotels that weekend increased 435 per cent.

The French attitude is awash with paradox and ambiguity. The first of these is that after more than a millennium of monarchy, the French executed their sovereign, Louis XVI, in 1793 during the French Revolution. But lest we forget, so did England in the seventeenth century.

Just like England, France also restored her monarchy. In 1814 the Bourbons returned and France would continue to live under royal tutelage until 1870 – excluding a four-year interlude from 1848. Even when the republic was proclaimed anew, after the humiliating defeat and capture of Emperor Napoleon III by the Prussians in 1870, the regime was not popular.

It was largely because French monarchists were divided among themselves over which branch should reign that the republic became established by default. Even under what became the early Third Republic, pro-monarchist parties continued to be elected and, but for their divisions, might have gained power in 1877. But, as one of the leading French politicians of the time, and no natural republican, Adolphe Thiers stated, republicanism is ‘the form of government that divides France least’. Yet to this day descendants of the three branches of the French monarchy (Bourbons, Orleanists, Bonapartists) occasionally surface in the many French royal-watching weeklies.

Even with the republican regime firmly in place, two other monarchist moments occurred, this time involving Britain. The first was in the spring of 1940 as the German armies advanced rapidly towards France. Prime minister Winston Churchill proposed to his opposite French number Paul Reynaud a Franco-British union, through which the two states would merge their two empires under the sovereignty of the British crown. Though at first taken seriously in Paris, the offer was finally rejected by the new Pétain government which had other plans. The second was in 1956 on the eve of the Franco-British Suez expedition when Paris made a similar proposal to London again involving the British sovereign that this time was rejected by Britain.

The French fascination with royalty continues to this day – albeit nuanced. According to a September 2022 poll in Le Figaro, 71 per cent of respondents said they had a positive view of the British royal family. The reason for this success was that for 80 per cent of the respondents the royal family was the incarnation of British values and 67 per cent found them sympathetic, while 70 per cent considered them close to the British people. Here we sense a French wistfulness for a regime other than the present republican system, where the head of state is an openly political figure and ipso facto a divisive force. For a nation so easily divided, it seems the republic is not the panacea Thiers thought it to be.

But does that make the French monarchists? The Figaro poll showed that 38 per cent of French respondents said monarchy ‘makes them dream’. This is an ambiguous statistic reflected in the fact that 55 per cent believe that monarchy is not adapted to today’s society, while on the contrary 44 per cent judge it to be ‘timeless and still adapted to today’s society’. Of particular significance is that amongst French under 35s monarchy is more popular (52 per cent) than amongst the over 65s (36 per cent).

One must imagine that French enthusiasm for monarchy is a vote-winner, because Emmanuel Macron is making such a big thing of King Charles and Camilla’s state visit to France this week – with a state banquet in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles thrown in and all. Some wags have already commented how Macron has often seemed to be more royalist than the King. Others, more threateningly, suggest he should beware the fate of Versailles’ last royal inhabitant.

Has the NHS forgotten its real purpose?

As doctors down stethoscopes and walk out of hospitals in their ongoing strike for better pay and working conditions, the public might reasonably conclude that the NHS is underfunded. How, then, do we make sense of this week’s revelation that NHS England is set to open three new departments focusing on equality and diversity? Either there are insufficient funds to pay doctors and nurses a decent wage or there is money to splash out on rainbow lanyards and unconscious bias training. Both cannot be true at the same time.

The three new NHS England departments, set to open in April 2024, will be called ‘Equality, Diversity and Inclusion’, ‘People and Culture’ and ‘People and Communities’. I am no highly-paid inclusivity expert, but it strikes me there is potentially some overlap here. Are the ‘communities’ and ‘culture’ staff not also concerned with equality, diversity and inclusion? And what about all the existing human resource officers? Are we to believe they are unconcerned about the employment rights of transgender nurses?

The phrase ‘jobs for the boys’ comes to mind, but it is no doubt outlawed as transphobic

None of this potential duplication seems likely to prevent the new centres from employing 244 people at a cost, the Daily Telegraph has uncovered, of almost £14 million. The dedicated Equality Diversity and Inclusion department alone looks set to spend £3 million employing 50 people.

The establishment of new departments with the same core purpose, the numbers of people to be employed in non-clinical roles, and the vast sums of money to be given over to these politicised concerns, all suggest this grand reorganisation plan is little more than a job creation scheme for diversity bureaucrats.

The phrase ‘jobs for the boys’ comes to mind, but it is no doubt outlawed as transphobic by multiple NHS style guides. Yet surely nothing else explains how senior NHS England officials, overseeing a health service with a record 7.7million people currently on waiting lists for treatment, can conclude that what is really needed right now is a greater focus on diversity and LGBTQ issues.

Even without these new departments, the NHS has managed to find time and money for promoting identity-driven, non-medical concerns. Right now, the NHS Business Services Authority is busy celebrating Bisexual Awareness Week. Staff are urged to ‘come together to share experiences, celebrate, and support our bisexual colleagues and friends’. Whether this awareness raising involves cake or a lecture is unclear.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph also notes that the General Medical Council (GMC), the regulatory body for doctors, has been busy updating its internal documents by deleting references to women. In an apparent bid to be transgender-inclusive, the word ‘mother’ has been removed from maternity policies and ‘women’ from its menopause guide. The GMC prefers gender neutral phrases like ‘surrogate parent’ rather than ‘surrogate mother’. It is committed to supporting not women but ‘individuals experiencing the menopause’.

The GMC’s internal policy documents matter because the organisation is responsible for improving medical education and practice across the UK. The language it adopts helps set the tone for the rest of the health service. Indeed, it is a sign of how successful this project has already been that there are now plans for three new equality and diversity departments. And all this comes despite Health Secretary, Steve Barclay, having already ordered NHS England to put an end to the expensive proliferation of such woke projects in a bid to ‘ensure good value for money’.

The cash dedicated to equality, diversity and inclusion does not just take away from the pay of doctors or the medical care of patients. It begins to alter the very purpose of the NHS. Decking hospitals with rainbow flags suggests they are not there to treat people who are physically sick but to correct the wrong-thinking of those deemed politically sick. The goal of the NHS risks becoming the correction of public opinion – and senior managers have seemingly unlimited access to public money to meet this aim.

There is a grim irony to NHS England considering spending even more on equality and diversity projects in the same week that doctors and consultants take unprecedented, co-ordinated strike action. Patients, especially cancer patients, will suffer as operations are cancelled and their treatment delayed yet again. Lengthy waiting lists will be extended further, with potentially life altering consequences for some patients. In one breath we are told the NHS has money for diversity vanity projects, the next we are informed that nurses need to use food banks. If both are true then taxpayers’ money has been shockingly misused.

Right now, only one thing seems clear. Both the striking doctors and the woke projects show that, despite all the saucepan-banging and rainbow-drawing during the Covid-19 pandemic, the British public’s love for the NHS is not reciprocated. Those in charge seem to hold us in contempt. They do not want to cure us but to re-educate us. We deserve better.

Be more Karen

In case you were under the apprehension that ‘Karen’ is simply an attractive name popularly given to girl babies in the early 1960s (my best friend as a child was called Karen, and there were three more in our year at my sink-school comprehensive) I’ve got news for you. To quote dictionary.com:

Karen is a pejorative slang term for an obnoxious, angry, entitled, and often racist middle-aged white woman who uses her privilege to get her way or police other people’s behaviours. As featured in memes, Karen is generally stereotyped as having a blonde bob haircut, asking to speak to retail and restaurant managers to voice complaints or make demands.

In other words, it’s a witless way to objectify and demonise non-posh women – you can’t pick on mothers-in-laws any more, but here’s a handy female stand-in punch bag.

This is yet another pathetic attack on women and the working class

I love my adopted hometown of Brighton, but it houses the biggest selection of over-privileged idiots you ever did see outside of ‘Glasto’. They’re the students, both actual and perennial, who voted in the Green council, the same one that has spent the past four years decimating our city. The pubs, once agreeable neighbourhood havens, have now been colonised by shrieking gaggles of the over-privileged with more of daddy’s money than sense. So naturally it would be Brighton that went after this modern hate icon, opening a restaurant called Karen’s Diner in which the staff are rude to customers.

Now one Karen, living in Worthing, has complained about this to the Brighton Argus: ‘It’s damaging for businesswomen called Karen and they are attacking a certain demographic. They are attacking women – have you ever come across a male Karen?’ A spokesman for the restaurant snootily responded:

Karen’s Diner combines a restaurant along with an immersive theatre experience. Certainly a sense of humour is needed to understand all comedy productions and Karen’s is no exception. The company identified that Brightonians, generally speaking, are more broad minded than most and eager to contribute to the status of being one of the most diverse cities in Britain.

Imagine if a name favoured by any other ethnic group was used as a synonym for being unpleasant. This is yet another pathetic attack on women and the working class, handily combined in one stereotype. Those who use the term try to weasel out of what in others they would call out as punching down by attributing privilege to their Karen. But if you are an educated person seeking to draw contempt towards a less educated person, how come that doesn’t count?

The only women called Karen I’ve ever known came from council houses. Why not call this privileged, arrogant white woman by a more accurate name, such as India, Emily or Charlotte? Because that would be implicating their own social group.

In 2020, academic Charlotte Riley and influencer Amelia Dimoldenberg recorded a podcast for BBC Sounds advising women how not to become Karens: ‘Educate yourself…’ giggled Amelia. ‘Read some books’. Charlotte added that white women should ‘think critically about your identity and your privilege… get out of the way’. ‘Yeah, basically leave’, agreed Amelia. What a smorgasbord of unreconstructed snobbery; middle-class women telling working-class women to shut up. As Brendan O’Neill put it

Many people will be asking why on earth they should be forced by law to fund a broadcaster that views them as Karens and gammons who must be saved from themselves by a new, supposedly enlightened elite. The public broadcaster should treat the public with respect, not insult them with classist diatribes disguised as academic analysis. Wokeness is the mask elitism wears, and the BBC needs to recognise that.

Karen isn’t the only villain to be found in the Names For Baby Girls book. There’s Natasha – ‘a prostitute, especially of Eastern European origin’ who was probably trafficked but, hey, probably no better than she should be. There’s Stacey – ‘an attractive but shallow woman’ often blamed by unattractive men for the fact that no one wants to have sex with them. Becky is ‘a white woman who is ignorant of both her privilege and her prejudice.’

It’s interesting that male names never become terms of abuse in this way; in 1965, the year Karen reached its peak popularity as the third-most popular girls name in the USA, the male counterpart was David. Do we ever hear said of a man ‘He’s a right David’? Tim-Nice-But-Dim was at least nice – Karens are irredeemably nasty.

We see this attempted policing of working-class white women in the reaction even to something as obviously positive as the rise of the Lionesses, who were criticised for being too white. Writing in Spiked, Inaya Folarin Iman summed up this weird behaviour well:

It is remarkable how ‘white’ has become a casual insult. To even remark that a team is ‘all white’ is to imply there is a problem that needs to be solved. This is incredibly demeaning to the England women, who have trained hard for years to earn their place on the team. Many would have made immense sacrifices to reach such an elite level – only to then be judged negatively for the colour of their skin.

With their lovely eyebrows and high ponytails, they wore the badges of their class and generation proudly, these gorgeous girls with names generally only heard on Love Island – Millie, Ella, Lauren. But who’s to say that these names won’t be the Karens of the future, so acceptable is it to pick on working-class women in this creepy, cowardly way, just for daring to stand up for themselves? In a world where women are increasingly encouraged to be #BeKind doormats, be more Karen.

The pointlessness of being early

We all know that the saddest words in the English language are ‘too late’. We also know that ‘procrastination is the thief of time’ and that ‘punctuality is the politeness of kings. However, since this piece was published a couple of weeks ago, many have got in touch to point out that, very often, ‘the tidy’ are also ‘the early’. Their irrational obsession with being tidy is matched by an equally irrational terror of being late.

They’re missing out on the joy of spontaneity, the thrill of uncertainty and of going with the flow

I’m not advocating a slack attitude to timekeeping. If you’re late for your train, your plane or your appointment at the Palace to receive your OBE, you really will miss it. However, if you’re perennially and pointlessly early, you’ll waste a significant chunk of your existence in a dull, lifeless limbo hanging around and killing time. And since your time is your life, isn’t continually killing it quite a wretched thing to do?

The problem with ‘the early’ is their pessimism. They’re forever fretting that something will go wrong – the train might be cancelled, they won’t get a good seat, there’ll be a monsoon on the M6 or a UFO on the M25. Their fears, of course, are usually baseless so their time is usually wasted. Their mantra – even though they don’t know it – is ‘hurry up and wait’.

Those of us who prefer to cut it fine are bright, sunny optimists. It rarely occurs to us that there’ll be impediments to our journeys or to our lives. And for the most part, there aren’t. Occasionally we come unstuck but isn’t that better than living in a state of constant anxiety – endlessly waiting, having needlessly panicked?

Anyone who lives with a temporal tyrant knows that this panic, like measles, is contagious and can affect the well-being of everyone around them. Their constant hurrying and harrying is likely to cause others to rush out without keys, phones or passports.

I speak as one who was once harassed by his cohabitant into leaving early for the airport and arriving there one hour before the check-in opened. That airport was Luton. Can you imagine a more soul-destroying place to kill time?

It’s at airports that you’ll witness the early at their most absurd. Even though airlines demand you check in two hours in advance for their convenience rather than yours, that still isn’t early enough for the early. You’ll see them glaring up at the departures board, unable to avert their eyes until their gate is shown. Once it is, they’ll charge towards it like greyhounds chasing a hare. But when they get there, despite having a boarding pass with an allocated seat, they can’t simply sit down and relax. They prefer, for absolutely no reason, to stand and queue. It’s the same at the other end. As soon as the aircraft comes to a halt, they’re out of their seats, pulling luggage from overhead lockers and standing impotently until they can disembark.

On one flight, I was, for the only time in my life, upgraded to business class. On my original boarding pass, it said to be at the gate 30 minutes before departure. On my new one, it said 15 minutes. Only a tiny thing – but so significant. I’d been awarded an extra 15 minutes of time, an extra 15 minutes of life. Since wealthy people are prepared to pay so handsomely to have more time in their lives, it seems absurd that the early give so much of theirs away. But they do.

How much of those lives have been squandered sitting in empty theatres long before the performance begins? Or in empty football grounds at least an hour before kick-off? Those same people will then leave the ground around the 88th minute ‘to beat the rush’ with the score at 1-1. Serves them right when they miss a spectacular injury-time winner.

And that’s the irony. The pointless panicking, the stress and strain they place on others with their neurotic dread of missing things means they’re missing out on so much more. They’re missing out on the joy of spontaneity, the thrill of uncertainty and of going with the flow. In short, they’re missing out on life.

It’d be good to think that the early might change their ways, stop trying to exert such control and enjoy fuller, more relaxing lives. But I doubt they ever will. To re-quote the saddest words in the English language, it really is too late.

Inside the Cornish home of John le Carré

Every writer needs a bolt hole. Novelist John le Carré’s was particularly picturesque, perched high above the waves on one of south Cornwall’s most glorious coastal stretches, between Lamorna and Porthcurno.

Tregiffian Cottage, made up of a trio of former fishermen’s homes, was where Le Carré conceived and wrote some of his most famous novels, including Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Smiley’s People, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and The Constant Gardener.

‘I love it here, particularly out of season,’ Le Carré, real name David Cornwell, who died in 2020, told a local newspaper. ‘The empty landscape, walking on the cliff, and the light, which of course everyone always mentions… but it seems that I can think well here. I can populate the empty landscape with my imagination.’

Le Carré first saw the huddle of cottages on a walk with his friend, Cornish landscape artist John Miller, in the late 1960s. Miller pointed it out to him, suggested he buy it, and the writer approached the farmer on the same day, settling on a reported purchase price of £9,000 for the 3.3 acre property.

With scene-stealing views to the Isles of Scilly and direct access to the South West Coast Path, it turned out to be a sound investment. Tregiffian Cottage was the writer’s long-term home but has now been put on the market by the family for £3 million.

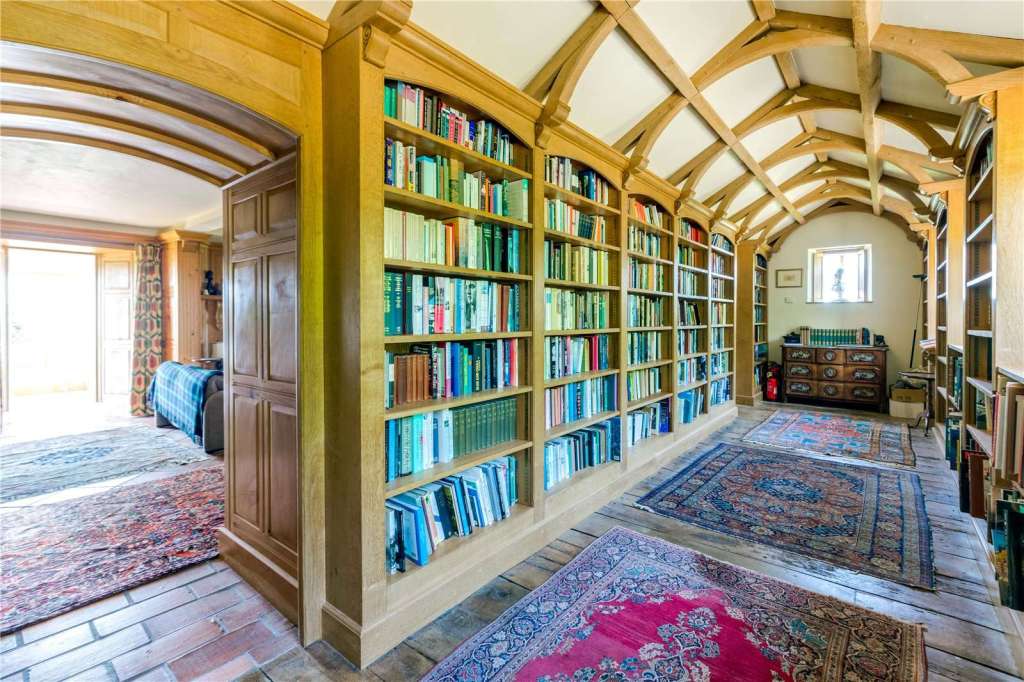

Le Carré, it seems, was also a dab hand at property renovation. He and his second wife, editor Valerie Jane Eustace, restored the cottages together, uniting the three into a single, 5,000-plus sq ft home for themselves and the four sons they had between them. They created four bedrooms (three ensuite), which includes a self-contained guest wing, plus a library with bespoke bookcases and a feature window at one end, glazed with what is believed to be part of the canopy from a second world war fighter plane. They also added a conservatory from where you can sit and watch the sweeping sea views.

They also renovated a range of outbuildings in the grounds, which contain a kitchen garden and greenhouses and are beautifully landscaped to make the most of the coastal setting. There are office quarters, an indoor swimming pool, gardener store and a workshop.

Crucially, Tregiffian was a creative sanctuary. Le Carré wrote the first of his novels, Call for the Dead, in 1961, while commuting from his home in Buckinghamshire to London where he briefly worked for MI5. But he used his Cornish retreat for nearly all his writing from 1970 onwards.

His fourth son, the writer Nicholas Cornwell, who goes by Nick Harkaway as his own nom de plume for novels including The Gone-Away World, Angelmaker and Tigerman, and who grew up at Tregiffian, tells The Spectator of his father’s disciplined work ethic. ‘In general, he had a rhythm,’ he says. ‘He woke early and had a quick breakfast in the kitchen, then went to his office – at various times what is now the living room, the lower east end of the house, and then the room above it… everywhere had its moment until the studio space in the outbuilding was created and became the firm favourite.

‘He needed quiet, regularity, and contemplation. I used to think his office door was closed to keep me out, but recently I realised it was at least as much to keep him in. He could easily get caught up making paper aeroplanes with me all day when I was a kid. So he was disciplined but distractable.’

His father’s gritty writing, often focusing on the political and human ambiguities of the Cold War, lent itself perfectly to star-studded small and big-screen adaptations. George Smiley was played memorably first by Alec Guinness in BBC TV’s 1979 adaption of 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and later to great acclaim by Gary Oldman in a film version in 2011. Oscar-winning Rachel Weisz and Ralph Fiennes dazzled in The Constant Gardener; more recently, Tom Hiddleston, Hugh Laurie and Olivia Colman thrilled in the glamour-soaked Night Manager, with Le Carré making a Hitchcock-style cameo as an offended restaurant guest.

Cornwall remembers an idyllic childhood at Tregiffian, a home filled with an eclectic art collection with pieces by members of the Newlyn School alongside works by German-born Karl Weschke, who came to England as a prisoner of war in 1945. ‘Furniture tended to be classic modern, often Italian,’ Cornwell says, ‘except in the kitchen and dining area, which was always and exclusively antique wood.’

His earliest memories, however, are of playing in the garden with his three half-brothers, Simon, Stephen and Timothy, and adventuring along the coastal path to St Loy or Mousehole. ‘The whole place is alive with butterflies, rabbits, swallows, foxes and occasionally badgers,’ he says. ‘In winter, you bank up a log fire and listen to the wind around the house and feel as if you’re in a castle or a lighthouse. The storms are dramatic and beautiful and when they’re gone you get that wild horizontal sun. It’s a wonderful place to rest, or work, or just be yourself.’

Cornwell says his mother – who died shortly after her husband – loved the clear, gentle air around Tregiffian, and remembers her most recently as laughing in the kitchen over lunch. It means, of course, that selling the home brings up a complex set of emotions for all the brothers.

‘We love the house, but it needs to be lived in,’ says Cornwell, simply. ‘It’s not a holiday home, it’s one of those places you put down roots. At the moment, there’s just no one in the family who can do that – and for me personally, it’s also an emotional rollercoaster just walking through the corridors. I see my parents at every corner. I want someone to make it entirely their own, not an echo, but a new place which will ultimately be something as defining and wonderful for them as it was for me.’

His own relationship with the rugged West Country is, however, an eternal one. He was born in Truro, in the hospital in which his father eventually died. Will he looking to set up another home here at some point? ‘Cornwall’s in me even if I’m not in it,’ he says. ‘But it would have to be somewhere different, and new – a story that’s mine to write.’

01872 243200, savills.co.uk

Rishi Sunak dilutes net zero

Here we go. As Rishi Sunak prepares for next year’s election, the government has been on the hunt for dividing lines with Labour. One of the areas in focus is net zero. When the Tories narrowly held on in the Uxbridge by-election, Tory MPs largely put it down to the campaign against Ulez (ultra low emission zone). It led to a debate on how far to go when it comes to scaling back environmental commitments. Aides in No. 10 have been debating the issue all summer and now Sunak is close to a decision.

This evening, the BBC reports that Sunak is considering weakening some of the government’s key green commitments in a major policy shift. This could include delaying a ban on the sales of new petrol and diesel cars and phasing out gas boilers. I understand both measures are likely. The thinking is both the boiler delay and that of petrol and diesel cars could potentially be done without legislation.

Sunak has since put out a statement confirming his general intentions: ‘No leak will stop me beginning the process of telling the country how and why we need to change. As a first step, I’ll be giving a speech this week to set out an important long-term decision we need to make so our country becomes the place I know we all want it to be for our children.’

As I understand it, Sunak’s speech will emphasise that he wants to keep the headline 2050 net zero commitment and he will try to emphasise his green credentials. The argument will be that by making such changes, the majority will come with you. Whereas sticking with policies that hurt voters could endanger the whole agenda. However, Downing Street is braced for a row – the sense is that the so-called Westminster bubble could take against the proposals, but voters could be more sympathetic. Recent rows on the continent point to the political risk when it comes to environment policies misfiring. The question is whether Sunak’s own party will buy it.

Did Indian agents kill a Sikh separatist leader in Canada?

Canada has accused India of being behind the assassination of a Sikh-Canadian citizen on its soil – an unprecedented charge to make against a democracy and fellow G7 nation. The Canadians claim to be investigating ‘credible allegations’ that Indian agents were behind the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Sikh separatist leader. Nijjar, a Canadian citizen, was shot and killed in June outside a Sikh temple in British Columbia.

Nijjar was long wanted by the Indian authorities, who accused him of involvement in an alleged attack on a Hindu priest in India and had offered a reward for information leading to his arrest. The manner of his death was bound to arouse suspicions.

To the Indian government, this is an existential struggle against people it views as enemies of the state

‘Any involvement of a foreign government in the killing of a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil is an unacceptable violation of our sovereignty,’ Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, told parliament. He said he had personally conveyed ‘deep concerns’ to his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi at the G20 summit earlier this month. Canada also announced that it was expelling a senior Indian diplomat as a sign of the seriousness with which it viewed developments.

India was quick to dismiss the Canadian claims as ‘absurd’ and politically motivated. It showed its own displeasure by expelling a senior Canadian diplomat. The Indian foreign ministry said the move reflected ‘growing concern at the interference of Canadian diplomats in our internal matters and their involvement in anti-India activities.’

So what is actually going on here? India has long accused Canada of not doing enough to tackle a rebel movement in the country looking to establish an independent nation called Khalistan in the Indian state of Punjab, where most Sikhs live. The independence movement is banned in India itself but has been attracting growing support in Canada and other countries, including Britain, which have large Sikh diaspora populations. Canada itself is home to more than 770,000 Sikhs – about 2 per cent of the country’s total population.

India is accusing Canada of being slow to act against people it claims are Sikh extremists threatening India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. It has also specifically accused Sikh activists in Canada of promoting violence against Indian diplomats, damaging diplomatic premises and threatening places of worship.

In the eyes of the Indian government, this is nothing less than an existential struggle against people it views as enemies of the state. Nijjar himself was branded a ‘terrorist’ by India for his pro-independence activism. Critics have, in turn, accused the Modi government of fostering a culture of intimidation, using sedition laws to crush any and every form of legitimate dissent and protest.

It is certainly true that India under Modi is no stranger to authoritarian tendencies, but the country’s fight against attempts to establish an independent Sikh state predates India’s current rulers. In 1984, Indian forces stormed the Golden Temple in Amritsar in a raid on Sikh separatists who had taken refuge there. The controversial assault led to the death of 400 Sikhs, even though activist groups claim the death toll was much higher. The controversial raid was ordered by the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi, who was assassinated shortly afterwards by two of her Sikh bodyguards. Her killing prompted a wave of anti-Sikh violence across the country, with Hindu mobs hunting down and killing Sikhs.

In fact, it is not just Modi’s government that is worried about the threat of Sikh independence. The Congress party, the main opposition party led by Rahul Gandhi, Indira’s grandson, echoed the Modi government’s stance on Indian sovereignty, saying India’s ‘fight against terrorism has to be uncompromising’. It is a rare moment of agreement between the ruling Hindu nationalists and their political opponents.

The spat between Canada and India comes at a time when relations between the two countries are already tense. Talks on a trade agreement have been paused, and a Canadian trade delegation to India, originally planned for next month, has been postponed. Other countries will be monitoring developments closely.

The White House has already said it is ‘deeply concerned’ about the Canadian allegations. Britain too will be keeping an eye on the situation, given recent events here: the Indian high commission in London was vandalised in March this year by Sikh independence activists.

India’s hostility towards the independence claims of Sikh activists is one thing. But the idea that this separatism dispute is slowly seeping into countries with large Sikh diaspora populations is a deeply troubling development.

The Met police is caught in a dangerous spiral

Twelve months after Sir Mark Rowley embarked on a mission to re-boot the Metropolitan Police following a wave of scandals, the force has revealed that it has suspended or placed work restrictions on a thousand of its officers.

More than 200 are currently suspended and 860 are on ‘restricted duties’ while criminal or misconduct allegations are investigated – taken together that’s as many as people as work in a small constabulary. In addition, there has been a 66 per cent increase in dismissals for gross misconduct – with 100 in the last year, and 300 more hearings in the pipeline. Scotland Yard says that before long, 60 cases of alleged misconduct or incompetence will be heard each month with a number of Crown Court trials due to take place as well, including those of two Met officers charged with rape.

The groundwork for this mass investigation of Met staff began shortly after the Commissioner took office last September, when he suggested that there were ‘hundreds’ of officers who shouldn’t be there. This was striking at the time. Can you imagine the chief executive of a major company saying that about their own employees?

Rowley then transferred 150 detectives into a new anti-police corruption and abuse unit tasked with examining internal wrongdoing. It was a statement of intent and an extraordinary investment of personnel and resources, particularly given how stretched public-facing parts of the force are. But it was necessary – as Baroness Louise Casey’s review later demonstrated.

Established after Wayne Couzens, a Met officer, had been jailed for the kidnap, rape and murder of Sarah Everard, Casey’s report exposed a rotten culture of defensiveness, denial and systemic bias within the force. According to Casey, predatory behaviour among officers wasn’t being picked up on, vetting and supervision had been allowed to slide and staff who complained were targeted. ‘There are too many places for people to hide,’ she wrote.

The days after her findings were published were dominated by a row over Rowley’s refusal to accept that the term ‘institutional racism’ applied to his force. But on the seventh floor of New Scotland Yard the leadership had already embarked on the biggest overhaul of standards for 50 years.

The new anti-corruption and abuse unit set up three operations, codenamed Onyx, Dragnet and Trawl, to carry out detailed checks on the Met’s 47,000-strong workforce and re-examine previous allegations of domestic abuse and sexual offences against serving officers and staff. A hotline was launched to report police wrongdoing and a new approach was devised to expel those who failed to comply with vetting requirements. They have all contributed to the startling number of internal investigations now underway involving those 1,000 officers.

Numerically, it provides firm evidence of Rowley’s commitment to change, but it also highlights a wider problem for the country’s biggest police force. It will take at least two, probably many more, years to get through all the cases, during which time the publicity will lead to more damaging headlines and potentially a further erosion of trust and confidence in the force.

The latest figures, collected by the London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, show trust levels in the Met are still on the decline and are now ten percentage points lower than they were before Sarah Everard’s murder in March 2021, at 70 per cent. In some inner London boroughs and among black and mixed ethnicity communities, trust levels are between 50 and 60 per cent. Even more concerning is the proportion of Londoners who believe the force is doing a ‘good job’. In 2018, around two-thirds said it was, now it’s less than half.

Critically, the upheaval in the Met and the flow of bad headlines are affecting efforts to recruit and retain officers. As part of the government’s programme to restore police numbers to the level they were in 2010, funding was made available for Scotland Yard to hire an extra 4,557 officers by the end of March this year. Although the workforce did expand significantly, the force fell 1,089 short of the target with the money for the ‘missing’ officers withdrawn. Sir Mark admitted that the recruitment difficulties were partly due to the ‘reputation of the organisation’ – and since then the problems appear to have worsened.

By the end of July, the number of officers, based on full-time equivalent roles, had fallen by 141 to 34,362 with applications for constables down to around 40 per cent of the level required. More than 200 officers are departing every month which means the force, with acute cost-of-living pressures in London and fierce competition from other employers and sectors, is destined to carry on shrinking. Earlier this month, the Commissioner said he feared Met recruitment was ‘going backwards’ and they would soon be 1,500 officers below the 35,000 he has been aiming for.

The more energy the Met puts into rooting out rogue cops, the more stories become public and the less attractive the force looks – to the public and those considering a career there. Deputy Assistant Commissioner Stuart Cundy, who’s leading the anti-misconduct drive, described it as a ‘paradox’, but he is under-stating the problem. It is in fact a dangerous spiral. Changes to the police misconduct system, intended by the Home Office to simplify procedures and make it easier to sack officers, cannot come soon enough – but they must go further. Officers who fail vetting checks and cannot be found an appropriate and genuine role should face immediate dismissal and the Ministry of Justice needs to consider ring-fencing courtrooms and judges to try cases involving the police. Some cases currently aren’t due to start until 2025.

Change is happening quickly in the Metropolitan Police. But unless the misconduct and criminal justice systems move faster, the force is going to be stuck with officers who shouldn’t be there and negative headlines for years to come.

YouTube is wrong to rush to judgement on Russell Brand

It is often on the back of public fury that dangerous new precedents are set. Authoritarianism can sneak in when we’re all hopping mad about something or someone. So mad that we don’t even notice that society’s rules are being rewritten in an illiberal way. I fear it’s happening again, with YouTube’s demonetisation of Russell Brand.

This is a risky thing to say. The climate is febrile right now. Criticise any aspect of the censure of Brand, following the publication of very serious allegations against him, which he strongly denies, and you risk being damned as a Brand defender. Worse, his weird online army, that ‘scamdemic’ mob that views Brand as a Jesus-like slayer of ‘the Covid regime’, might mistake you for a fellow traveller. Guys, please don’t.

Tribalism has warped the discussion of the Brand scandal

So I’ll clear my throat before asking what the hell YouTube is up to. That there apparently exists evidence that one of his accusers attended a rape-crisis centre following her alleged encounter with him makes this an issue of the utmost seriousness. That there is apparently a text message in which the woman said: ‘When a girl say[s] NO it means no’ is troubling in the extreme. The press has every right to report on what these women claim to have experienced. Brand, for his part, has said that his relationships were ‘always consensual’.

What’s more, I think Brand’s fanboys have behaved appallingly over the past few days. In my view, their insistence that ‘our boy’ is being stitched up by a globalist cabal is conspiratorial drivel. Their dismissal of Brand’s accusers as handmaidens of the lockdown regime doing the anti-Brand bidding of their masters is cruel and misogynistic. Their delusions of oppression – as if the capitalist class would plot to take down some saddos who think we’re living through a vax genocide – is laughable.

And yet, even in times like this, especially in times like this, it is important we keep our cool. Especially where liberty and justice are concerned. And YouTube, to my mind, is wrong to suspend Brand’s income. Such a significant restriction on a man’s ability to earn a living, such a severe form of economic reprimand, is surely a punishment that should only be inflicted when guilt has been established by law?

YouTube is preventing Brand from making money from his videos on the basis that he is ‘violating’ its ‘creator responsibility policy’.

‘If a creator’s off-platform behaviour harms our users, employees or ecosystem, we take action’, a spokesperson said. It is estimated that Brand made a million quid a year from his zany vids. Now, by decree of an American corporation, he no longer will.

Who would feel sorry for a rich brat like Brand, right? Especially one who faces serious accusations of sexual assault. Not so fast. We should feel very uncomfortable indeed that a multi-billion-dollar entity, an unaccountable business oligarchy headquartered in California, has made itself judge, jury and executioner on an affair that might well become a matter for the courts. That some suits have decreed in their infinite wisdom that Brand has fallen foul of their ‘off-platform behaviour’ guidelines, and thus must be punished.

Who would feel sorry for a rich brat like Brand, right?

It is not the role of Google – the owners of YouTube – to determine the guilt or innocence of any individual. How dare they. This smells to me like a corporatist usurping of the democratic institutions of justice. It is a snub to the right of everyday citizens to see justice done in a fair, open, rules-based way that Silicon Valley has rushed to judgement and rushed to punishment. They’re penalising Brand, yes, but they’re insulting us.

Some will say: ‘YouTube is a private company, so it can decide for itself who to host and who can make money on its platform.’ Okay, but some of us – me included – are not free marketeers. We believe society has a right to curb the behaviour of big business, especially where it impacts on consumers, users and citizens. And restricting the right of huge corporations to pre-empt the potential judgement of the courts, and to infer guilt against the accused, seems proper to me.

I no more trust Google and YouTube to rule on the morality or legality of a citizen’s ‘off-platform behaviour’ than I would trust an unelected dictator to do so. Give us a jury or give us nothing.

There has been a furious discussion about the presumption of innocence since the Brand allegations came out. Some say this presumption only applies in court, when the individual is being prosecuted by the mighty state. In everyday public chatter, in contrast, people can make any presumption they want. Technically this is right, though I do worry that devaluing the presumption of innocence in the court of public opinion risks devaluing it in courts of law. More to the point, though, while I’m okay with Joe Public making their minds up about Brand, YouTube and Google are a different matter entirely. I don’t want corporations with extraordinary cultural power and economic clout to presume guilt in anyone. You shouldn’t, either.

Tribalism has warped the discussion of the Brand scandal. His haters have damned him already, his followers insist he’s morally spotless. But I don’t want society to be organised according to hunches. We need calm, we need reason, we need to treat the accusers with respect, and we need to insist that no one’s life be destroyed on the basis of accusation alone. It’s a difficult principle to adhere to right now, but it is so much better than the alternative.

How do authors’ gardens inspire them?

When Henry James moved to Lamb House in the Sussex coastal town of Rye, he admitted that he could hardly tell a dahlia from a mignonette: ‘I am hopeless about the garden, which I don’t know what to do with and shall never, never know – I am densely ignorant.’ He sought advice from the artist and designer Alfred Parsons and fortunately Lamb House already had a gardener, George Gammon, to do all the work. When Gammon won prizes at local horticultural shows, James was delighted: he was a vicarious gardener, more comfortable at his desk in the Garden Room than with his hands in the soil.

Thomas Hardy was at the other end of the gardening spectrum. Born in Dorset in the thatched cottage at Higher Bockhampton that his grandfather built, he grew up helping in the kitchen garden and orchard, trading apples for access to books with a friend whose father was a bookseller in Dorchester. When Hardy designed a new house in Dorset for himself and his wife Emma, he planned the garden before Max Gate was built. There were three distinct garden areas, including one where his plays could be performed, surrounded by woods that he helped plant with pine, yew, laburnum, elder, beech, bay, box, laurel and plane trees. ‘It was the trees that Hardy really cared about,’ Jackie Bennett writes in her sumptuous coffee-table book. Hardy’s description of Giles Winterbourne’s gentle hands spreading out roots before planting saplings in The Woodlanders reflects his personal experience.

Between the extremes of James and Hardy, Bennett describes 26 other writers’ gardens, some from outside the UK, and provides up-to-date visitor information. Each alphabetically arranged entry is generously illustrated with photographs by Richard Hanson, and accompanied by a short note on the ‘Writer in Residence’. This structure allows the writers to be glimpsed briefly, passing through beautiful spaces that have outlasted them.

Sometimes the writers transformed their gardens into words – Frances Hodgson Burnett immortalised the grounds at Great Maytham Hall in The Secret Garden, Rudyard Kipling caught the spirit of his Sussex garden at Bateman’s in The Glory of the Garden – but all the gardens have matured and rejuvenated beyond the tenure of the resident writer. Apples are a recurring theme. Louisa May Alcott referred to the drafts of her novels as ‘green apples’. When her parents bought an old farmhouse in Concord, Massachusetts, and named it Orchard House, the garden there inspired the garden in Little Women, where each sister has her own section of flower-bed. Since the 1990s the Orchard House grounds have been carefully restored with new plantings of heritage apple trees that would have been grown in Louisa’s childhood including the eating apple ‘Baldwin’ and the cooking apple ‘Rhode Island Greening’.

When he died in 1963, Jean Cocteau left his house and garden to his gardener

Karen Blixen spent most of her life in Rungstedlund, her parent’s manor house north of Copenhagen. She returned there after her divorce from Bror von Blixen-Finecke, with whom she had lived in Kenya, and from whom she had contracted syphilis. When she was in her seventies a local gardener cultivated and named an eating apple after her: Malus domestica ‘Karen Blixen’. Rungstedlund was opened to the public in 1991 so visitors can appreciate the writer’s work as a conservationist alongside her accounts of big game hunting in Out of Africa.

In Jean Cocteau’s garden at Milly-la-Forêt there is a moat and a partially walled verger: ‘Four squares of lawn divided by paths lined with trained apples and pears.’ Among the trees are heritage varieties ‘Reine des Reinettes’, ‘Belle Joséphine’ and ‘Beurre Hardy’. Cocteau grew grape vines against the walls which still thrive and underplanted the trees with irises and herbaceous peonies. When he died in 1963, Cocteau left the house and garden to his gardener, who lived there until 1995, when he died and was buried next to Cocteau beneath the floor of the chapel.

At Yasnaya Polyana, his family estate 130 miles south of Moscow, Leo Tolstoy planted 200 young apple trees: ‘And for three years I dug around them in the spring and the fall, and in winter wrapped them with straw against the hares.’ Bennett explains that ‘for Tolstoy, apple blossom was a symbol of renewal and life. When the blossom came, everyone – from the landowners to the peasants – joined in this feeling of wellbeing and good fortune’. The weblink for visiting Yasnaya Polyana is included under ‘Garden Visiting Information’. Around 100 of the apple trees planted in Tolstoy’s lifetime still bear fruit. Perhaps there will be peace again in our lifetimes and it will be possible for foreigners to visit and see the apple blossom as Tolstoy would have wished.

A 50-year obsession with the white stuff: Milk, by Peter Blegvad, reviewed

It’s been a while since I read a good cento, from the Latin and derived from the Greek, I need not remind Spectator readers, meaning ‘patchwork’, and thus a literary work composed of quotations from other writers, the earliest known example being Hosidius Geta’s Medea, consisting entirely of lines from Virgil and which is almost as good as it sounds. Contemporary literary centos, or cento-like creations, include a lot of very bad found poems but also Graham Rawle’s simply incredible Woman’s World (2005), a novel collaged from cut-up lines from women’s magazines, and David Shields’s profoundly plagiaristic work of literary criticism, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (2010).

Peter Blegvad’s Milk: Through a Glass Darkly, as one might perhaps expect, is something different. Blegvad is truly unclassifiable: a writer, artist and musician perhaps best known for his work with the 1970s avant-garde bands Slapp Happy and Henry Cow. Or perhaps he’s best known for his long-running cartoon strip in the Independent, Leviathan, which was the thinking man’s Calvin and Hobbes? Or for the indescribable ‘eartoons’ that he used to produce for BBC Radio 3’s The Verb? Maybe ‘best known’ is overstating it: Blegvad is truly one of those writer’s writers, an artist’s artist and a musician’s musician. He’s also a long-standing member, apparently, of the London Institute of ’Pataphysics, inspired by the work of Alfred Jarry, with whom Blegvad might justifiably be compared. He’s one of those people who just makes and does very strange and beautiful and interesting things.

Milk is very interesting: for Blegvad, it’s been an obsession. As he explains in his Q-and-A-style introduction, this is a work that’s been 50 years in the making. He started collecting material when he was 20: ‘I’d just read about Alfred Hitchcock putting a light in a glass of milk and the image seemed portentous, freighted with meaning. I began collecting quotes that confirmed my hunch that milk, even without a light in it, and despite the normalising efforts of dairies and marketing boards, is numinous, psychically active.’ What this lifetime’s hoard now amounts to is about 350 numbered, lightly edited and loosely connected remarks about milk, its colour, its smell, and much else.

Sources range from the obvious (Roland Barthes’s essay ‘Wine and Milk’, Claude Lévi-Strauss’s The Raw and the Cooked) to the rather more recherché (Lewis Carroll’s ‘Musings on Milk’, from the Rectory Magazine) and the distinctly occasional (a quotation from a review by Fiona MacCarthy of two books about cosmetic surgery, excised from the New York Review of Books).

It’s not exactly an easy read. Much of the material is odd, and not just because it’s out of context: it would be distinctly disturbing in any context. ‘Toads thrive on burning cigarette ends and human milk. Some 40 years ago I had to read The Letters of Junius. All I remember is that one of the royal family was “subject to the hideous suction of toads”’ (Evelyn Waugh, letter to Ann Fleming, 3/3/1964). ‘Haven’t I always been a cannibal? As a child I sucked my mother’s breasts, draining her flesh. I longed to taste the salt of her blood through the salt of milk, trying to replace the blood that used to come to me through the umbilical cord, to flow through me like alcohol through an alcohol addict’ (Josip Novakovich, ‘In the Same Boat’).

Make of it what you will, on one level the book is merely a compendium but on another it amounts to a kind of autobiography, a portrait of the self, mediated through milk. Glowing, elemental, otherworldly and full of natural goodness, Milk has gotta lotta bottle.

Vivid, gripping and surreal: a new slice of Ellroy madness

Los Angeles, August 1962. PI and extortionist Freddie Otash is snooping on Marilyn Monroe for labour leader and racketeer Jimmy Hoffa, who’s paying good money for dirt on Jack and Bobby Kennedy. Is Jack really schtupping Miss Monroe? Who cares? Make it so.

But the operation is rumbled and then Monroe dies of an overdose (or does she?) and Otash finds himself pushed from pillar to post by greasepole Pete (Pitchess, 28th Sheriff of LA County) and ratfink Bobby (US attorney general Robert Kennedy), for they too have a stake in filthing-up the film star’s name. Maybe, through it all, Otash can find who and what really got her killed – but not without betraying the woman of his dreams (the Kennedys’ sister Pat Lawford), or facing up to his great weakness (which, this being Ellroy, is obedience to powerful figures even less principled than he is).

This entire book is one gleefully violent foul-mouthed research note. It’s vivid, gripping, surreal

So another gobbet of post-war West Coast history descends screeking down the Ellroydian waste disposal, in a book you will have to devour at speed lest in its violent madness it devours you – the latest in Ellroy’s planned new ‘LA Quintet’ and the third in the sequence after This Storm. Never mind the labyrinthine plot (Ellroy is a writer you don’t so much read as investigate); pop to the prose. His signature telegraphese has never felt more naturalistic, ensuring him perpetual squatter’s rights in that stylistic flophouse thrown up by James Caine and Dashiell Hammett.

Ellroy is not without his issues, of course. No need to fret about the drug-pickled corpse around which his delirious noir entertainment churns. No need to take on the burden of her aggravating stupidity, or think your way into her last miserable minutes. She’s Marilyn Monroe, which means you’ve already seen her in a film or read about her in a book; you know Ellroy’s Marilyn is neither your Marilyn, nor the real Marilyn; and so you know we’re just playing charades here, that every punch is telegraphed and every drop of blood is jam.

Otash is a historical figure, too. So’s everyone. There’s next to no one in The Enchanters’ cast who doesn’t have their own Wikipedia page. And just because this approach is classic Ellroy doesn’t stop it from being a mistake.

This entire book is one gleefully violent, foul-mouthed research note. It’s unputdownable, vivid, gripping, surreal, and it’s also, at a spiritually corrosive level, untrue, in a way that fiction need never be.

‘Jimmy, Jimmy, Jimmy,’ as some goon in The Enchanters might sneer, yanking the strappado, ‘why give yourself this pain? You’re supposed to lie.’

The chase looms large in the best new thrillers

The ‘chase’ thriller is the fallback choice of writers looking for an easy way to make the pages turn. The Continental Affair (Bedford Square, £16.99) shows a gifted writer embracing the more obvious traits of these novels, while adding some innovative twists of her own. The story is set during the Algerian war that led to independence; its co-protagonist Henri is a former Algerian gendarme, of French and Spanish descent, who deserts when he is made to interrogate a childhood friend. Henri takes refuge in Grenada among his late mother’s family – countless cousins, and all of them crooks. As they get to know Henri, the cousins decide to give him a task which is also a test: he’s sent to collect a package left by a woman in a courtyard. But another, mysterious, woman beats him to it, and leaves with what Henri can see are bundles of banknotes.

Louise, the unknown woman, is English, recently released from a life spent looking after her invalid father; her mother scarpered years before. When the father finally dies, Louise takes the £40 she finds in the house and goes to Spain. There, as her money is about to run out, she witnesses the drop. Grabbing the cash, she heads for Paris, where her mother was last heard from many years ago. Following her, Henri vows to recover the money, but each time the opportunity arises he finds an excuse not to act, to the growing consternation and eventual fury of his cousins.

The novel is told in what is at first a slightly confusing alternating time-frame, but as we start to make sense of it the story becomes engrossing. There are occasional historical references – such as the 1961 Paris massacre of Algerians by the French National Police – but not enough to distract from the book’s spotlight on the unlikely travelling pair. Both are wounded souls; both also sense this in the other, enough to unburden themselves. Though Christine Mangan’s story ends with a classic sort of confrontation, what persists for the reader is the troubled duo at the book’s deeply imagined heart.

The bird of Louise Doughty’s A Bird in Winter (Faber, £16.99) is a family nickname for Heather, an officer in the secret service, who after 20 years in its employ inexplicably gets up in the middle of a staff meeting, leaves the room and doesn’t come back. Thereafter, she’s on the run – though from whom and why is only gradually made clear, since interspersed with her flight is a jerky but compelling account of her earlier life.

Saffy’s expertise with corpses proves useful when a severed head is left by Jon’s front door

Before intelligence work, Heather was in the army, where she formed a close friendship (subsequently ruptured) with another soldier, named Flavia. Heather otherwise keeps her distance from everyone. She is a tough but emotionally dislocated woman who sleeps only with older men, does not want children and excels at the duller parts of her work – strategy and liaison – that no one else is good at.

It is not an actionless book – when at one point Heather is found, there follows a scene of truly gruesome violence – but its strengths lie in the rich if piecemeal portrait of Heather that gradually emerges. As the book moves towards its unusual climax, Doughty reverts to more conventional thriller mode – like an angler who, happy to let a hooked fish run, suddenly remembers the purpose of the exercise and quickly reels it in. We discover who has betrayed whom, enjoy a well conceived twist and get all the answers to the questions we ask when Heather first goes on the run. It is not badly done at all, but seems slightly disappointing after the unusual narrative that precedes it, as well as the deceptively casual prose, which is masterfully attuned to the laconic, even depressed mindset of its heroine.