-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

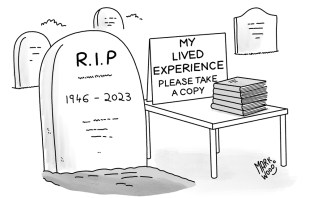

Deus ex machina: the dangers of AI godbots

Something weird is happening in the world of AI. On Jesus-ai.com, you can pose questions to an artificially intelligent Jesus: ‘Ask Jesus AI about any verses in the Bible, law, love, life, truth!’ The app Delphi, named after the Greek oracle, claims to solve your ethical dilemmas. Several bots take on the identity of Krishna to answer your questions about what a good Hindu should do. Meanwhile, a church in Nuremberg recently used ChatGPT in its liturgy – the bot, represented by the avatar of a bearded man, preached that worshippers should not fear death.

Elon Musk put his finger on it: AI is starting to look ‘godlike’. The historian Yuval Noah Harari seems to agree, warning that AI will create new religions. Indeed the temptation to treat AI as connecting us to something superhuman, even divine, seems irresistible.

New godbots are coming online – and we should be afraid. They raise two serious concerns: first, they are powerful tools that bad actors can use to victimise others; second, even when well-intentioned, these bots trick users into surrendering their autonomy and delegating ethical questions to others.

The temptation to treat AI as connecting us to something superhuman seems irresistible

It’s important to understand what is novel about godbots. Bots such as ChatGPT which employ a relatively new technology, LLM (Large Language Models), are trained on enormous amounts of data and capable of performing astonishing tasks. At the same time, these apps are not new in their ability to satisfy the human desire for answers in times of uncertainty. They exploit our tendency to impute divinity to inexplicable processes by speaking in certainties. Our response to AI is strikingly similar, therefore, to how humans have always reacted to the power and inexplicability of divine and godlike figures – and, more specifically, to the ways we try to get the gods to talk to us.

Let’s begin with a central feature of the new AI – its ‘unexplainability’. Algorithms trained by machine learning can give surprising and unpredictable answers to our questions. Even though we built the algorithm, we don’t know how it works. It seems as if the thing has a mind of its own.

But the problem, more precisely, is that we can’t explain how the algorithm gets the results it does and that any explanation we can give is at least as long and as complicated as the algorithm we are trying to explain. Like a map that’s so detailed it ends up the same size as the territory it’s supposed to depict, repeating the algorithm simply doesn’t help us grasp where we are. We haven’t got a proper explanation. As a result, the workings of the device seem in-effable, uninterpretable, inscrutable.

When such ineffable workings produce surprising results, it seems like magic. When the workings are also incorporeal and omni-scient, it all starts to look a lot like something divine. God’s reason is indescribable – mysterious and beyond human comprehension. By these measures, the AI in GPT-4 seems godlike. We may never be able to explain why it gives the answers it does. The AI is also body-less, an abstract mathematical entity. And if not utterly omniscient, the algorithm has access to more information than any human could ever know.

GPT-4 seems to open a conduit to something truly potent. And so we want it to answer our hardest questions. One of the most widespread techniques human societies have used for seeking answers from a god is divination, trying, for example, to read the movements of birds or casting lots.

Traditionalists on the Indonesian island of Sumba practise several kinds of divination, such as reading the entrails of animals and certain operations similar to casting lots. But they don’t do this for ordinary technical or agricultural questions. They turn to divination when they face uncertain and troubling circumstances, especially moral or political ones. And they don’t try to explain how divination works – it remains opaque, which is surely part of its power.

Divination was common in the ancient world. Cicero, a skeptic, worried that divination would be used by charlatans to manipulate users and trick them into doing their bidding. It is not hard to see how the same dynamic will play out with godbots. Malicious actors need only insert code that makes the godbot respond in the way that the malicious actor wants. On some existing apps, Krishna has already advised killing unbelievers and supporting India’s ruling party. What’s to stop con artists from demanding tithes or promoting criminal acts? Or, as one Chatbot has done, telling users to leave their spouses? When God asks you to do something, you don’t say no.

It’s easy to think there is a gulf between our scientific, secular present and the benighted, superstitious past. But in fact, those who are not religious may still retain, in secular form, a yearning for magic under the stress of uncertainty or loss of control. When the magic consists in interpreting the words of an all-knowing, unimaginable and disembodied device – something like GPT-4 – it can be like talking to a god.

AI chatbots tap into our desire for magical thinking by speaking in certainties. Even though their large language models employ sophisticated statistics to guess the most likely response to a prompt, the bot replies as if there is just one answer. They imply there’s nothing more to discuss. Bots won’t tell you their sources or offer links inviting you to consider alternatives. They will not or cannot explain their reasoning. Where once the gods spoke through entrails, now there’s an app.

What can we do about this? Like divination, AI seems independent of its creators. But, like divination, it is not. Behind the hype, self-learning programs depend on human input. Even traditional diviners didn’t take the signs at face value, they interpreted them. Their answers had input from human beings, even if disguised. When AI scrapes the web, it reflects back to us what we have put there. Our apps should show this. They should be required to present some of the evidence relevant to their decisions. This way users can see the artificial intelligence is drawing on human intelligence. Bots should not speak in absolutes and spurious certainties. They should make clear they are only giving probabilities. They should not speak like divine beings that magically know the answer.

AI is made by humans and can be constrained by humans. We should not give AI divine authority over human dilemmas. Humans are morally accountable for their actions. As agonising as some ethical issues are, we cannot outsource them to snippets of code. AI will only become godlike if we make it so.

Where has Xi Jinping’s foreign minister gone?

This is the week that James Cleverly planned to be in Beijing to ‘engage, robustly and also constructively’ with China’s communist leaders. But the Foreign Secretary put his trip on hold because the man he planned to engage went missing. Since 25 June foreign minister Qin Gang has vanished without trace, leaving Cleverly twiddling his thumbs and the world wondering what on earth is going on at the top of the Chinese Communist party. The whole bizarre spectacle underlines the challenges of engaging with a system that is so deeply opaque.

The mystery deepened on Tuesday when state media reported that Qin was being replaced by his predecessor Wang Yi after just seven months in the job. There was no explanation, and no word on the fate of Qin. ‘Qin Gang has been removed as foreign minister. Wang Yi has been appointed as the Chinese foreign minister,’ ran a terse statement in the CCP’s Global Times.

The vacuum surrounding Qin’s disappearance has been filled with all manner of rumours

It has been a strange and surreal few weeks, even by CCP standards. Every mention and image of Qin has been deleted from China’s foreign ministry webpage. The information vacuum surrounding his disappearance has been filled with all manner of rumours about marital infidelity, a love child – and even foreign espionage.

His sudden departure is all the more intriguing because he is a protégé of President Xi Jinping. He was regarded as a rising star, one of the new generation of snarling ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats, pleasing his boss with tirades against a decadent and declining West. A former ambassador to the United States, he was appointed foreign minister in December ahead of others regarded by China watchers as more senior. Shortly afterwards, he accused the US of ‘all-out containment and suppression’. He said his country’s friendship with Russia was a beacon of strength and stability which ‘set an example for foreign relations’ and asked: ‘Why should the US demand that China refrain from supplying arms to Russia when it sells arms to Taiwan?’

That said, those who knew him say he could be charming and open, and he was expected to play a key role in putting relations with America back on a more stable footing. The best explanation that the foreign ministry spokesman Mao Ning was able to offer after his disappearance was that she had ‘no information’, ‘no knowledge of the situation’, and that ‘diplomatic activities were continuing normally’.

Ill-health is a possibility. That was suggested when Qin was replaced as head of Beijing’s delegation to a regional summit in Jakarta. But there seems no reason why a health issue should be covered up, especially when the absence of information fuels the rumours – rumours given further currency when CCP censors scrubbed his name from the internet. A search for ‘where is Qin Gang?’ returned ‘no results’ on China’s social media platform Weibo.

Speculation has centred on an alleged affair with Fu Xiaotian, a high-profile Cambridge-educated television personality. This theory created a particular frenzy in Taiwan, amid further rumours that Fu has had Qin’s child. When asked about these unsubstantiated claims, the hapless Mao Ning said, ‘I have no understanding of the matter that you’ve raised’ – which wasn’t quite a denial.

The problem with this hypothesis is that for all Xi’s apparent concern with moral rectitude, keeping a mistress is not unusual among the grey men who run China. And when they have been caught out, the party has tended to protect its own. This was the case in 2021 when the tennis star Peng Shuai accused the retired Chinese vice-premier Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault. They had been involved in a long extramarital affair, but in this case it was Peng who was disappeared.

Neither are disappearances uncommon in China. The party’s anti-corruption inspectorate runs its own dark network of jails and interrogation centres into which business people regularly vanish for weeks or months. The trouble with this explanation is that anti-corruption probes are frequently thinly disguised purges of Xi’s opponents, and Qin was – or at least appeared to be – a Xi loyalist.

Another rumour is that Qin might have been compromised in some way – even that his alleged mistress was a double agent. Fu tweeted from what appeared to be a private jet parked up in Los Angeles in April, sharing three photographs: the aircraft, an image from an interview she’d conducted with Qin, and a selfie of her cradling her baby. That tantalising post was her last before she too seemingly vanished.

The very fact that the standing committee of China’s rubber-stamp parliament, the National People’s Congress, met this week to endorse the removal of Qin and appointment of Wang is itself highly unusual. The committee is a creature of habit. It usually meets every two months and was not due to convene until August. This special session was scheduled just a day in advance and had only two items on the agenda. Strangely, Qin remained listed as a state councillor, a senior rank in China’s cabinet.

Whatever has happened to Qin, the CCP has opted for a safe pair of hands to replace him: Wang is one of China’s most experienced diplomats. Immediately before his reappointment, he was director of the CCP’s foreign affairs arm and is a known quantity in the West. As for Qin, one of the few things that can be said with a fair degree of certainty is that if he has been purged it reflects extremely poorly on Xi’s judgment. But at least Cleverly now has somebody to talk to – even if the inner workings of the government he wishes to engage are murkier than ever.

Listen: Nigel Farage snaps at ‘condescending’ Nick Robinson

Nigel Farage blasted Nick Robinson for his ‘condescending tone’ during a fiery interview on the Today programme. The BBC host asked the former Ukip leader whether he was planning a political comeback following his run-in with Coutts bank. But Farage lashed out at Robinson, telling him he was ‘sick to death’ of his line of questioning:

‘I’m really not going to have this. I am sick to death of your condescending tone. No, no actually you weren’t. What you should say to people is, “you’re the only person in British history who has won two national elections leading two different parties.” Let’s try that for size shall we.’

Farage was referring to his successes in European elections in 2019, with the Brexit party, and 2014, when Ukip won 24 seats: the first time a party other than Labour or Conservative had won the largest number of seats in a national election for over 100 years. But Robinson instead focused on Farage’s failure to make it into the Commons. He asked Farage:

‘Pretty much whatever you do there are people saying: “I know what this is about, he wants to get back into politics”. I know you’ve run seven times and lost seven times…’

This morning’s interview came hours after NatWest boss Dame Alison Rose resigned over her handling of the Farage ‘debanking’ scandal. Rose had previously confessed to being the source of an inaccurate briefing to the BBC about Farage’s Coutts account.

Farage might be forgiven for not liking the BBC over its conduct in this story – now, it seems, Robinson has just given him another reason to dislike the Beeb…

Socrates meets Keir Mather, the new Labour MP for Selby

SOCRATES: I was walking back from the gymnasium when I saw Keir Mather, the new MP for Selby, on his way there. I had been told he was young and good-looking and went to a world-famous Oxford College, so I have been very keen to meet to him.

Hello, O Keir.

MATHER: And you too, Socrates. But what, therefore?

SOCRATES: Now that you are an MP, you must tell me what justice is. For that surely is a lawmaker’s main concern.

MATHER: Enough verbal games. Justice is defined by the laws. My job is to solve problems in the real world.

SOCRATES: Are Tory laws, then, just?

MATHER: Of course they are not!

SOCRATES: But you said…

MATHER: And I will change them and, I quote, by ‘my ability to process information and communicate it to people effectively, and to analyse complex problems and find frameworks through which to implement solutions’.

SOCRATES: Splendid – crystal clear! But come now, here is another problem to solve: what is a woman?

MATHER: Obviously, anyone who asserts that they are.

SOCRATES: So is asserting that you are someone exactly the same as being someone?

MATHER: How not, O Socrates?

SOCRATES: And if I said I was prime minister?

MATHER: Be very careful, Socrates. These days we do not think like that.

SOCRATES: Or at all. Come now, this justice of yours, is it of advantage to the community in the real world?

MATHER: Of course!

SOCRATES: But it is clearly not advantageous to the community, O Keir, for a man, who can fight, to become a woman, who cannot fight, nor have children. Would you not pass a law against it?

MATHER: But that is not a legal matter, Socrates, but one of human rights. Presumably you have never heard of them.

SOCRATES: True. We preferred not to live in a world of make-believe, where anyone could become anyone they liked merely by asserting it.

MATHER: Welcome to 21st-century reality, O Socrates.

Is 2023 a bad year for forest fires in Europe?

Boss pay

Julia Hoggett, chief executive of the London Stock Exchange, complained that FTSE 100 bosses aren’t paid enough, and suggested that the gap between UK bosses and US bosses needs to be closed if the London market is to prosper. How much are FTSE 100 bosses paid?

– The median earnings in 2021 for a FTSE 100 boss was £3.41m and the mean £4.26m. Three were paid less than £1m, 57 between £1m and £4m, 35 between £4m and £10m and three more than £10m. Two changed jobs during the year and so aren’t included in the figures

– But the best-paid FTSE chief executive wasn’t even in the FTSE 100. That was Frederic Vecchioli, CEO of FTSE 250 company Safestore, who earned £17.06m.

The next best-paying companies were:

Endeavour Mining (FTSE100) £16.85m

AstraZeneca (FTSE100) £13.86m

CRH (FTSE 100) £11.68m

Carnival (FTSE 250) £11.31m

Anglo American (FTSE 100) £9.83m

Up in flames

Is 2023 a particularly bad year for forest fires in Europe? According to the European Forest Fire Information System, between 2003 and 2023 an average of 346,294 hectares of land in the EU was burned by fire. This is approximately 0.08% of the total area of the EU.

– The average area of land burned up to 22 July is 128,000h. This year, up to that date, 173,000h had burned. In the worst year, 2022, 561,000h had burned; in the best year (2008) 19,000h had suffered that fate.

– Greece has now had its worst year for fires since 2003, with 35,000h burned by 22 July, compared with an average of 26,914h in the previous worst year. Greece’s whole-year average is 43,000h.

Breast vs bottle

How many babies are breastfed?

Nationally, 48.8% of babies were being breastfed at six to eight weeks in the third quarter of 2022/23. The districts with the highest recorded rate (although the data doesn’t cover all of England) were:

Lewisham – 81.7%

Kingston upon Thames – 76.8%

Windsor and Maidenhead – 76.2%

Bristol – 67.8%

Bath and North East Somerset – 67.2%

Those with the lowest rate were:

Halton – 26.7%

South Tyneside – 27.6%

Durham – 30.1%

Redcar and Cleveland – 31.7%

Stockton-on-Tees – 31.9%

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities

Inside Ukraine’s drone army

Kyiv

‘We will end this war with drones,’ says Mykhailo Fedorov, deputy prime minister of Ukraine. We meet at the Ministry of Digital Transformation, which he runs in Kyiv. It has become crucial to the counter-offensive. To reclaim occupied land, Ukrainian troops need to remove miles of landmines, and can do so only if kept safe by swarms of drones that fly ahead, searching for the enemy. Russia has drones too – many more of them – and is adept at jamming and downing Ukraine’s fleet. A drone arms race is under way.

Soon after his election, President Volodymyr Zelensky asked the then 28-year-old Fedorov to run a new ministry aimed at turning Ukraine into a digital country (or, as he put it, a ‘paperless state’). At first, the idea was to move common government services on to an app called Diia. Once the war intensified, the brief soon expanded to defence procurement. Fedorov’s remit was to bypass a slow-moving and often fraud-addled civil service. He hoped to incentivise and energise both the voluntary and private sectors. The aim was to out-produce and out-innovate the Kremlin.

‘We’ve signed more contracts with drone manufacturers in the past two months than in all of last year’

At 32, Fedorov is now a veteran. His ‘Army of Drones’ programme has been designed to encourage Ukrainian companies to make thousands of drones and train a similarly large number of operators. This unprecedented collaboration of private enterprise and the national military has so far seen 12 drone assault companies created, with about 65 soldiers apiece. Fedorov says six more will be created soon. ‘We would like drone assault companies in each brigade.’

The objective is to make drones more quickly than Russia can shoot them down. There are no official numbers, but some estimates have said Ukraine is losing 10,000 a month. When Vladimir Putin invaded last February, only seven companies in Ukraine supplied drones to the army, in large part because many others had been driven abroad by high taxes and regulations. Now there are 40 firms making drones directly for the defence ministry, with more on the way. Fedorov has created incentives: there are fewer custom checks and restrictions, red tape has been cut and companies can make a 25 per cent profit on any drones they sell. Until recently, the cap was 1 per cent.

‘We’ve signed more contracts with Ukrainian drone manufacturers in the past two months than we did all of past year,’ says Fedorov. Now it takes just six weeks to secure a deal, when it once took years. Combat testing and price assessment are carried out by the military, and feedback is then delivered. ‘You make the improvements, and the state gets to know you for future contracts,’ says Fedorov. ‘But everything that the state does can be done more effectively by business and an active public.’ Even the training of drone operators, like the drone-making, is done independently of the government.

Military drones come in all shapes and sizes, with prices starting from as little as £300 each. There are fast, single-use kamikaze drones and grenade drones, small enough to be held in one hand. A more recent development is the semi-submerged boat drone, which has been used to attack Russian warships and bridges, often in co-ordination with aerial drone attacks.

But manufacturing drones is the relatively easy part; finding and importing enough components to launch the production process and keep it going are much harder. Entrepreneurs are urgently needed.

One such is Ihor Krynychko. When I visit his little factory outside Kyiv, Krynychko shows me a pile of paper that he’s barely able to lift. It gives him permission to operate and secure contracts to supply his reconnaissance drones to the front. ‘It is five times less than what was required before, but it’s still a lot,’ he says.

Soldiers who buy drones often avoid putting them on the brigade’s balance sheet, he tells me: ‘If a drone is lost, it takes a lot of paperwork and a whole investigation to write it off.’ He gives me one of his drones to hold – a silver plane as light as a children’s toy.

Some of the drones sent to the front line by the defence ministry can end up unused, because of the bureaucracy involved if they get damaged. At present, official inquiries are launched after the loss of equipment worth more than £6,000. Fedorov has proposed raising this tenfold, but a final decision is still pending.

Krynychko, 56, tells me that his Sirko drones (which each cost about £3,000) have won approval to be supplied to the front line. He is an example of a drone-maker brought into the industry by the war. He studied aviation engineering in Kharkiv but ended up as a businessman. In the first days of last year’s invasion, he met a friend who had joined the army. ‘I asked him, “How do you find Russians in our forests?” He replied: “I go to the forest, and if they shoot at me, I know they are there.”’ Krynychko thought he could use his engineering background to invent a homemade drone that could provide intelligence to the front line.

‘I wanted not only to make a cool plane, but also one that could be made in the kitchen, and produced in large batches so that it could make a difference at the front,’ he explains. A team of 30 people make up to 100 per month, which are mostly sold to Ukrainian individuals who donate them to the front line. Much kit now comes from such donations. Krynychko’s government contract means he can supply the army directly. He has also received Nato codification for the Sirko, which allows him to export them. ‘I will sell my drones to Brits,’ he says.

The Sirko can transmit video from 15 miles away and fly for 40 miles on one battery charge. It can also turn off its own GPS navigation and fly back to base should it be detected by the enemy. This is helpful, because the Russians are good at GPS ‘spoofing’, where they down drones by scrambling their navigation.

Krynychko has the capacity to produce up to 2,000 Sirko drones a month, but needs quality components and financing in order to do so. Chinese companies have been going cold on supplying Ukrainian buyers, he says, showing a preference for Russians instead.

Krynychko offers one-week training for those working with his drones, but learning how to use reconnaissance aircraft needs serious tuition. To this end, private drone schools have sprung up all over Ukraine. There is no state regulation of how this should be done, just official criteria (the ability to fly the drone a certain distance, perform a set task without losing control of it and so on). To speed up the process, certification is overseen by the schools. Entrusting such crucial military work to new, untested schools is quite an experiment.

One of the schools is Drone Fight Club, hidden in a Kyiv suburb. When I arrive, I see no signposting. If its whereabouts were ever to be discovered, it would be a prime target for Russian missiles. The school is run by Vladyslav Plaksin, a professional pilot who now makes LuckyStrike and FPV drones and teaches soldiers how to use them.

We enter a room with seven computers where 20 students are training to fly drones using simulators. They learn in 20-minute sessions and spend two weeks practising on computers. In week three, soldiers are taken to fields outside Kyiv for target practice with real drones. There’s a weekly exam, and anyone who fails it is removed from the school.

‘I always say that before you give out a graduation certificate, you need to trust the student enough that if your loved ones were next to him when he was going to fly a drone with a bomb, they would be safe,’ explains Plaksin. Operators attach the explosive and ready the drone for take-off: getting it wrong can have calamitous consequences.

‘As a drone operator, you bear responsibility not only for yourself but also for those soldiers working with you. They provide cover with machine-guns, automatic rifles and grenade launchers, ensuring your drone’s safety, but they risk their lives for a purpose, because you bring results, and you are worth it,’ he says.

Drone Fight Club provides free training for soldiers but refuses to grant certificates if commanders don’t allocate enough days for them to complete the course. ‘We know time is tight and that people are needed at the front,’ says Plaksin. ‘But this drone could accidentally kill half a unit of soldiers. Even its battery can become explosive, if it is not properly connected.’

The government pays about £170 to the schools for every graduated FPV- drone operator. Some schools offer rapid three-day training courses, but 50 qualified specialists are better than 500 bad ones, he believes. The lack of regulation, while helpful in many ways, does increase the risk of cowboy drone schools offering shoddy training while still claiming money from the government.

I watch Etti, a Drone Fight Club instructor, train the students. He deliberately makes the job tricky at times to watch how the soldiers adapt: turning off the camera on the drone or slightly adjusting a setting. ‘There won’t be greenhouse conditions at war,’ he says. ‘We try to provide every student with at least 20 hours of real flying per course.’

He tells me how he has seen soldiers change over the past year or so: ‘Young conscripts come to drone school with their eyes burning, eager to learn. They romanticise it. When they return from the war, I don’t see that flame any more. It goes out.’

So far, 10,000 operators have come through Fedorov’s Army of Drones programme. He wants to double this number by Christmas. Some will be redeployed to drone assault companies; others may return to drone units within their brigades. Fedorov says that soldiers who train to fly drones are not guaranteed exemption from other duties. ‘This is war, and they could be reassigned as sappers or drivers.’

Too many pilots would be a good problem to have. For now, Fedorov wants as many drones and people to operate them as is possible. ‘There will always be a shortage of drones,’ he says. ‘There will only be enough when we restore Ukraine’s borders of 1991.

Was I right about Iraq?

Back in March there was a glut of pieces about the 2003 Iraq war. The 20th anniversary seemed to much of the political and pundit class to be the perfect time to return to this scorched landscape. A number of people asked me to throw in my views and I failed, for two reasons. Firstly because, as some readers will know, I hate anniversaries and the lazy hook they provide to the news cycle. Secondly, because each time I sat down to try to write about those days I found myself unusually conflicted.

Those of us who defended the war have spent 20 years filled with ‘if onlys’

The reason partly relates to the wonderful, heroic former Labour MP Ann Clwyd, who died last week at the age of 86. After the war’s height, as the insurgency had begun, I went to Iraq with Ann. By then she already had a long and respected history of advocacy for the Iraqi people, and particularly the Kurds. This had come from visits from the 1980s onwards, when she saw for herself the terrible plight of the people whom Saddam Hussein had attempted to ethnically cleanse in the Anfal campaign and afterwards, through gassing, bombing and more. When Ann contributed to the parliamentary debate on the second Iraq war, the House was silent. Amid all the talk of WMD and more, here was a committed campaigner who could tell people first-hand the horrors of Saddam’s regime. It was a case I was in agreement with and to my great good fortune we became friendly.

Today there are no minds to change on Iraq. Those who opposed the war understandably point to the disaster that unfolded. Those of us who defended the war (many more at the time) have spent 20 years filled with ‘if onlys’ and agonised attempts to work out where it all went wrong.

Since Ann’s defence of the war was on principle, she did not waver. Tony Blair appointed her as special envoy on human rights in Iraq and on her visits she would dig into new problems as well as historic ones. She was welcomed by Kurdish officials like a queen. Their respect for her was incalculable. But she did not rest.

We spent part of our time inspecting Iraqi jails. These included some pretty hair-raising moments in cells packed with jihadists the authorities had picked up. In one Kurdish-run prison we met an Iraqi pilot whom the Kurds accused of involvement in the 1988 Anfal campaign. Ann wanted to be sure that the Kurds weren’t mistreating him.

It had been after seeing the Kurds fleeing across the mountains during that campaign that Ann’s interest in the Kurds grew. She was one of the formative figures in a group called CARDRI (the Committee against Repression and for Democratic Rights in Iraq). And while most of the world learned the name Abu Ghraib only in 2004, Ann was one of the few westerners who had known of the prison for decades, and knew what had gone on there while the Hussein family were in charge. I remember one torture cell we visited, from before the war, where a young Kurdish boy had carved into the wall ‘They are trying to change my age so they can kill me’. The unknown boy had obviously not been old enough for execution, so the authorities found their way around it.

There was plenty of such grimness. But Ann was an undaunted, positive presence. One day we travelled for hours to Kirkuk to see an official for yet another briefing on the latest situation. Our small group were all exhausted, the heat was suffocating, and in the early afternoon I noticed Ann’s eyes start to close. None of us had had any sleep and the other person in our party tried, with me, to cover over. I did that thing of suddenly accentuating words, but the midday heat soon did for me too. There was at least one period where I fear all of us were asleep. I remember waking, mortified, realising that this poor official had been sitting behind his desk while these strange British men and women napped in front of him.

But the truth is Ann was truly unflagging as well as brave. Her own vision of a post-Saddam Iraq did not emerge, though it sometimes seemed close. There were plenty of ‘what ifs’. One day we visited a Kurdish centre in Erbil and in the hallway and all the way up the stairs were huge framed photos of their heroes. These included, though were not limited to, colossal framed photographs of Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle. By then none of these men were much loved at home, but this corner of Iraq was grateful. History is complex when you’re going through it.

My own inability to make a full mea culpa over the years comes in part from that trip – and one day in particular. We were crossing the long mountain pass to Sulaymaniyah, near the Iranian border. It happened to be the day of Nowruz, celebrated by the Kurds as their New Year. During the Saddam years the celebration of this festival had been violently stamped out. But this year the Kurds were free, and as we wound through the mountain passes people poured out from every building. Men and women emerged from mud houses dressed in a finery that would be hard to pull off with the best tailors and dry cleaners in Mayfair. This huge colourful human wave spent the morning driving or walking into the green mountains. Up there, families and whole villages were picnicking, and by every roadside and on every mountaintop these men and women in traditional Kurdish dress were dancing their traditional Kurdish dance. Ann and I got pulled in. I can see that wonderful broad smile now as we joined the happy, strangely shuffling line.

All that magical day I had the strangest feeling of déjà vu and couldn’t work out why. It only dawned on me later. It was the scene in Narnia after the defeat of the White Witch. The land – this bit of the land at least – had been unfrozen and spring had finally come back.

Nothing can wash out the disaster. But when people talk about Iraq they want a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. To me it seems, at the very least, to deserve an ‘and also’.

Why does the Beano want to cancel itself?

Let’s hear it for the Beano, 85 years old this week. Lucky readers can get a commemorative issue featuring Charles and Camilla, Dua Lipa and Lewis Hamilton. It’s also a chance for those who haven’t read it for decades to register how much it has changed. Lately, the Bash Street Kids welcomed five classmates: Harsha, Mandi, Khadija, Mahira and Stevie Starr. There’s a hijab alongside the stripy shirts and school caps, plus a scientist in a wheelchair. Fatty, the boy who ate all the pies, and Spotty, who had pustules and a long tie, have been renamed Freddy and Scotty to ensure young people who have freckles, weight problems or acne are not taunted by their peers.

Censorship works best when it’s internalised. You pre-empt criticism

The comic’s creative director, Mike Stirling, cheerfully admits that the comic has become ‘woke’. ‘We have never seen that as a pejorative term,’ he says. ‘It’s awareness and being awake to things. What would be easy to do would be to sleepwalk and keep the Beano the way it had always been done for ever.’ As in, funny?

The Beano’s changes testify to the influence of Inclusive Minds, a consultancy ‘for people who are passionate about inclusion, diversity, equality and accessibility in children’s literature’. The organisation encourages those it works with to sign its ‘Everybody In’ charter, which declares that ‘everyone working with children and books must play a part in ensuring that all children can find authentic representations of themselves in books, as well as seeing those who are different from them’. Its ‘inclusion ambassadors’ – children and parents – advised on the Beano’s makeover.

The organisation, founded a decade ago by Alexandra Strick and ‘inclusion and equality consultant’ Beth Cox, surfaced earlier this year as the body involved in censoring Roald Dahl’s work for children. You know, the one that ended with Puffin and the Roald Dahl Story Company removing the words ‘fat’ and ‘ugly’. The Oompa Loompas were no longer men, but people. Miss Trunchbull’s horseface disappeared. Some disobliging verses in James and the Giant Peach were rewritten, but the new ones didn’t scan quite so well. In The Witches, a paragraph explaining that witches are bald beneath their wigs ends with: ‘There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.’ Indeed! It’s just not what Dahl would ever have said.

That exercise went well, didn’t it? The agenda rolls on, with Inclusive Minds advising the big five publishers and a number of smaller ones on how to embed inclusivity in their writing, editing and illustration. ‘We do not edit or rewrite texts,’ it insists on its website, ‘but provide book creators with valuable insight from people with the relevant lived experience that they can take into consideration in the wider process of writing and editing.’

I’m not sure the big figures in children’s books quite realised that this is how the agenda works. Sir Quentin Blake – quoted in the Inclusive Minds testimonials praising the aim to ‘ensure all children can see themselves reflected in stories and pictures’, (something he does in his own work) – did not care for the Dahl rewrite, not least because he was Dahl’s illustrator. He told me last week: ‘If the work is wrong, it’s wrong. If it’s crude and insensitive, we need to know that… If the sensitive had their way, [Dahl] would never have written The Twits at all.’

Of course, Inclusive Minds is only one element of the transformation of children’s publishing. The drive for greater diversity and inclusion began, as you’d expect, in the US, where public libraries helped lead the changes. In the UK, the agenda is driven by organisations like the Vital North partnership and Seven Stories: the National Centre for Children’s Books, which brings public funding into the equation.

And let’s not forget the Equality Act. A friend who runs a Montessori school told me that she was making sure there were enough books featuring gay dads and non-nuclear families in her school library because they were expecting an Ofsted inspection, and that’s something the inspectors look out for. Ofsted’s remit under the Act’s public sector equality duty is to ensure that schools promote respect for ‘protected characteristics’. So if your toddler is bringing home Julian Is a Mermaid, Grandad’s Pride – Grandpa went on the original Pride parade with his black partner – or The Kindest Red: A Story of Hijab and Friendship (a little girl learns to celebrate her sister’s hijab), that may be why.

All this has changed how authors, publishers, editors and illustrators work. I spoke last year to the head of a distinguished publishing company who told me that while they do not themselves employ sensitivity readers, she finds herself changing what she commissions and how she steers her authors. In other words, the agenda is in her head. That’s how censorship works best – when it’s internalised. You pre-empt criticism.

Need I say I don’t have a problem with children of different ethnicities or cultures featuring in children’s books? Some of the most vigorous children’s books I have reviewed over the past few years have been from African authors. One of the best books published this year is Alan Garner’s Folk Tales, featuring Indian epics as well as Celtic sagas.

The problem is that as an agenda, diversity and inclusion doesn’t make for good writing. It meddles with the work of our favourite old authors and makes for new story-telling that’s didactic, prescriptive, propagandistic. The sin is that it introduces criteria to publishing other than that a story should be well and grippingly told and illustrated in an evocative, distinctive way. As for adult stories, let’s not even go there; but let’s just say that James Bond is only the start.

The problem with the Bibby Stockholm barge

For British taxpayers perturbed by their £6 million daily bill for housing asylum seekers in hotels, New York City mayor Eric Adams has the solution: handbills. Exasperated by a sudden influx he characterises as a ‘disaster’, Adams plans to dispense police-tape yellow flyers both at the city’s 188 sites for housing migrants and at America’s overrun, purely notional southern border. The leaflets warn in English and Spanish: ‘Since April 2022, over 90,000 migrants have come to New York City. There is no guarantee we will be able to provide shelter and services to new arrivals. Housing in NYC is very expensive. The cost of food, transportation, and other necessities is the highest in the United States. Please consider another city as you make your decision about where to settle in the US.’ Well, that’s one colossal headache sorted, then. Why didn’t anyone think of flyers before?

In addition to three ‘culturally appropriate’ meals a day, migrants will enjoy a 24-hour food service

I’m reminded of being paid a pittance to distribute leaflets for a Little Richard concert in Atlanta in 1973 – a thankless task. Most pedestrians wouldn’t accept one. A few politely did, then immediately threw it away unread, often on the pavement; this was largely an exercise in secondary littering.

I had no idea that such modest slips of paper would prove the ingenious answer to a municipal crisis 50 years later. Why, now that the Big Apple is falling back on retro advertising tactics, let’s skywrite above the Rio Grande, ‘Don’t ♥ New York!’ Or maybe Adams should try his hand at radio jingles: ‘Other cities hit the spot. Ninety thousand, that’s a lot. Twice as much for a burger, too. Other cities are the place for you!’

Yet aside from exhibiting a certain, well, ineffectual quality, these leaflets are brandishing the high cost of necessities at a population that doesn’t plan on paying for them.

Now more than half occupied by new immigrants, NYC’s homeless shelters are bursting. Like Britain, the city has resorted to putting up foreign arrivals in hotels. One institution recently block-booked is the Roosevelt, a majestic four-star art deco landmark near Grand Central Station. This is where for three decades the bandleader Guy Lombardo welcomed in the New Year with ‘Auld Lang Syne’. ‘The rooms are outdated but they’re gorgeous,’ says a hotel security guard. ‘The migrants are going to think they landed in heaven. They’re never going to want to leave.’

Indeed, why leave? New York’s asylum seekers are provided with free health care, free NYC ID, help enrolling children in free public schools, free food, free legal counsel, as well as free accommodation in a city whose average rent for a two-bedroom flat is over $5,000 (£3,900) a month. Bike New York gives asylum seekers free bicycles.

Alas, these gratuities are not free for benefactors. The city is leasing each of the Roosevelt’s 1,025 rooms for 36 months at $200 a day, totalling $219,000 per room. For each migrant family, the average cost of emergency hotels is half as much again at $339 a day. The city expects to spend a budget-busting $4.3 billion on recent migrants, thanks to the five-and-a-half million-plus illegals who’ve crossed the US border during the Biden administration. Idiotically, NYC’s provision of shelter to anyone who shows up has been enshrined as a legal obligation. As a ‘sanctuary city’ that refuses to enforce federal immigration law, abstractly New York may deserve this fiscal nightmare, but its taxpayers do not.

The UK’s solution to its whopping hotel bill for migrants isn’t a flyer, you’ll be relieved to learn – but a barge. The Bibby Stockholm, which docked last week in Dorset, can house 500 migrants with en suite baths. The government boasts that asylum seekers will be provided with guided walks, trips to farms and sports events, festival excursions and biweekly English lessons.

In addition to three ‘culturally appropriate’ meals a day, migrants will enjoy a 24-hour food service. They’ll have full NHS access, as well as an on-board nurse and clinic, and be offered nearby allotments for cultivating vegetables and flowers. (Um – many Londoners wait years for an allotment.) The barge is kitted out with gyms, sports facilities (football, basketball, volleyball and netball), two TV rooms, five lounges, an IT room with laptop computers and free wifi, a courtyard with picnic tables, a multi-faith room, another room for ‘quiet reflection’, and a conference room bookable for meetings or hobbies. Residents are free to come and go, either on free hourly buses, or in a free taxi back if they miss the last bus home. They may be gone for up to a week at a time, but if migrants exceed this limit the management will ring up and ask if they’re OK.

A few tiny problems. One, in the three days before the Home Office’s proud announcement about its new luxury barge, 1,100 Channel migrants were apprehended: more than twice the boat’s capacity. Try over 100 barges. Two, money: the department is paying the NHS £1,900 per bed, Dorset council £3,500 per migrant plus a £380,000 block grant. Maybe the barge is cheaper than hotels, but all those laptops and 24-hour nachos add up. Three, if New York’s experience is any guide, the Bibby Stockholm won’t stay pristine for long. According to a former worker at the Row Hotel near Times Square – housing 5,000 migrants in 1,300 rooms, for which the city pays $500 each per night – officialdom’s hospitality is prone to being abused. The Row’s rooms are strewn with rubbish, drink, clothes, guns, drug paraphernalia and used condoms, their bins overflowing with free food that the residents don’t like.

Tiny problem number four: boiling popular rage. In both New York and Britain, comments after articles about the opulent Roosevelt hotel or the amenity-rich Bibby Stockholm explode with an apoplectic sense of injustice and betrayal. Besides, if this is deterrence, I’d love to see what come-hither looks like.

Letters: Labour’s shameful defence of Ulez

Unfair Ulez

Sir: I hope Ross Clark’s article (‘Highway robbery’, 22 July) will open people’s eyes to the unfair disadvantage Sadiq Khan has been imposing on those on lower and middle incomes in London. As a jobbing gardener who relies on the use of a van, I had just paid off the lease, with the intention of keeping the vehicle until I retired, when I became a victim of the first expansion of the Ulez zone in 2021. I live 200 metres within the boundary: driving that 200 metres in and out to go to work costs me £12.50 a day.

Ulez is a regressive tax that falls particularly hard on the elderly and disabled, as there is no exemption for Blue Badge holders (Labour GLA members voted down a proposed amendment by the Conservative group to allow an exemption). If people in these groups fail to qualify for the higher rate of disability allowance, they are more likely to depend on older vehicles.

It is shameful that Labour has been responsible for this tax, which seems part of a drive to make mobility the privilege of the rich once again. That high-pitched whine you can hear is the sound of my late father and his fellow lifelong Labour activists and supporters spinning in their graves.

Bob O’Dwyer

London SW4

Breakdown

Sir: Ross Clark writes that ‘As reality has set in, it has become clear there is a limited market for [electric] cars’. This despite Ulez and similar schemes across Britain. We all know about the limits to recharging infrastructure and battery life but a point that hasn’t been made as much is what happens when they break down. Roadside assistance can’t get them back on the road. Worse, they are immobilised when the electrics malfunction, and cannot be pushed out of the way. The result is that they remain blocking the traffic until the emergency services show up. I returned mine to the secondhand dealership after three weeks.

Chloe Green

London E9

Who banks there?

Sir: You correctly state that the public has the right to know what is happening within Coutts and NatWest (‘Held to account’, 22 July). The key question both banks need to address is whether they still have pro-Kremlin oligarch account holders and, if so, why they have failed to close their accounts.

Trevor Lyttleton

London NW11

Defence of LNER

Sir: Mary Wakefield (‘There is no plan!’) and Martin Vander Weyer (Any other business, both 22 July) isolate LNER for criticism. I travel fairly frequently from Newark to London and had to do so last Thursday, a strike day. LNER gave me a week’s notice of a special timetable. I booked through their app, a simple process, and received the tickets on my phone at once. In uncomfortable anticipation I went along to the station. The train arrived two minutes early and was surprisingly empty. The seats (standard class) are acceptable, and all was well cleaned. The staff were polite and helpful and happy to engage in a little light banter about the strike. We were two minutes ahead of schedule at King’s Cross. I am sorry that Ms Wakefield and her fellow passengers were poorly treated at Thirsk. Apart from the occasional train delayed by theft of cables or an attempted suicide, I have generally experienced excellent service from LNER. Please allow the alternative view to balance your correspondents’ experiences.

Tom Fremantle

Newark, Notts

A way out

Sir: Douglas Murray is correct to warn of the ‘slippery slope’ that can follow the introduction of assisted dying laws for patients with terminal diseases (‘Canada’s lovely, liberal solution’, 22 July). However, this is not an inevitable consequence and should be avoidable with good legislation. It is also important to remember that despite the invaluable work of hospices and their outreach methods, palliative/terminal care is not as widely available in the UK as would be ideal. This is one of the many tragedies of the NHS. Over-concerns about the ‘slippery slope’ denies choice to patients with full capacity suffering from, for example, intractable pain or paralysis from bone metastases, or the distressing breathlessness of end-stage pulmonary fibrosis or the indignities of terminal motor neurone disease and some other neurodegenerative diseases. With the true compassion of a mature society, a safe and sustainable solution, without slip, should be the goal.

J. Meirion Thomas, FRCP, FRCS

London SW3

Right to Buy

Sir: A letter (22 July) in response to Lionel Shriver offers various reasons for and solutions to the current housing shortage. From my working life in social housing, I now believe that the introduction of Right to Buy was the main problem for both social and affordable housing availability. It removed the best of the stock, often in desirable areas with the highest need, and ridiculously generous discounts were given. The money made from the scheme should have been used to provide more council housing but was not. I am glad that in most areas it is back to being a discretionary policy. If only local authorities and housing associations had been allowed to offer mixed-tenure housing from the start, as well as offering a percentage for sale. That in turn would have been a better source of cross-subsidy.

Ian Elliott

Belfast

Made in Dagenham

Sir: In his review of Different Times: A History of British Comedy (Books, 22 July), Joel Morris mentions that Dudley Moore’s Dagenham roots were often overlooked. But so too were those of George Carey, the former archbishop of Canterbury, and of Sandie Shaw, who won Eurovision in 1967 with ‘Puppet on a String’.

Peter Inson

East Mersea, Essex

In defence of Coutts

Dame Alison Rose should not have resigned as head of NatWest over the Nigel Farage affair – and ministers who forced this by flinching in the face of a silly media storm should be ashamed of themselves.

In the great Coutts debate this columnist finds himself in a minority. I express no opinion on the wisdom or otherwise of the private bank’s decision to drop Farage as a client, believing this to be a private matter between himself and Coutts.

I’ll pose a number of questions, but first there’s something we must get out of the way. Whether or not Coutts was wise to exclude Farage, a bank like this has, as the law stands, a right to discriminate in its choice of customers.

Customer-facing businesses do often, and should, enjoy a right to reserve admission to premises or membership. No publican could survive long without that implicit right. One of the charming ironies in which our era abounds is that the very people who (as a type) would wax indignant in support of the Garrick Club’s denial of full membership to women, or the Athenaeum’s insistence upon male members wearing a tie at dinner, find themselves on the other side of the argument when a private, members-only institution excludes a would-be customer because his publicly expressed opinion, rather than his gender or neckwear, offends them.

Aren’t there causes that, though lawful, you or I or a respectable bank might consider wicked?

So, point one: a private bank enjoys the legal right to choose its customers. Now for point two. Was the bank’s judgment wise in this case: the exclusion of Farage? I shall not attempt to answer that here. I have an opinion. You may have an opinion. The bank took a view. We can all argue about it.

Or can we? That is point three, and the question I want to discuss in this column. I’m adding to the general noise about the Farage affair only because I haven’t read or heard any attempt to answer it, and it matters. The question is: does a category exist, whether or not Farage falls into it, of clients whom it would be reasonable to reject on the grounds of the public stands they have taken?

I ask, because so much of the Coutts–Farage debate last week appeared to wheel in a somewhat cosmic fashion around the ‘right to free speech’. A typical opening sentence in many of these discussions ran along the lines of ‘Whether or not you agree with Nigel Farage’s views on Brexit [/net zero/Novak Djokovic/etc], and I don’t [/do/will keep my counsel/etc], it surely cannot be right…’ and the commentary then proceeds to maintain the importance of a citizen’s right to express their opinions, and the wrongfulness of any business disadvantaging anyone for their famously declared beliefs.

Woah! The implication here is by no means incontestable. Any beliefs at all? Any level of fame at all? Really? Let’s examine a range of possible beliefs a bank customer might – I say ‘might’ – become famous for publicly supporting. Anti-Semitism (the kind that stays within the law)? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Insulting the monarch? Anti-vax campaigning? Denying the Holocaust? The persecution of Christians abroad?

I’ve chosen here a few causes that – were a prominent customer of a bank to trumpet them – might particularly enrage some of us on the right-of-centre of British politics. Were I writing for the New Statesman, I might have chosen causes like sending illegal immigrants to Rwanda, re-criminalisation of abortion/homosexuality/blasphemy, ‘anti-trans’ ranters, eugenicists… Each of us has our particular bête noire and no Spectator or NS reader would want their bank to exclude every public apologist for every one of these causes. But quite a few readers would hesitate to join a bank with a famous customer whose name was prominently associated with one or another of them. Remember, we’re not talking about private thoughts or speech, but prominent and public proselytising – and I stress ‘prominent and public’. If someone makes themselves famous for – trades upon – an odious, hateful or even treacherous opinion or association, would it always be wrong for a bank at least to consider what Coutts called ‘reputational’ issues? I think not.

The key phrase, I suppose, is ‘beyond the pale’ – and our leading article last week identified this as the line we should ask whether Farage has crossed, suggesting he had not crossed it. Fair enough. But what if someone did? Our leader points out that if disliking the EU is beyond the pale, so are millions of our countrymen. Fair point. But how about one of those dodgy imams the press call ‘preachers of hate’? They might attract large numbers of followers yet still be – in your or my eyes – beyond the pale. Aren’t there causes that, though lawful, you or I or a respectable bank might consider wicked? Without censoring anyone, may we not decline to associate ourselves with them? The problem with discussing this as though it were just a question of freedom of expression is that the argument is too strong.

A final point: there’s no way we can in principle distinguish between removing an existing client for given reasons, and for similar reasons declining to accept someone who applies for an account. But banks turn down applications all the time, often to the fury of the applicant. Are we suggesting that applications either to keep or to acquire a bank account should be in some way publicly justiciable if the would-be client does not like the decision? Our leading article’s call last week for some kind of official inquiry in Farage’s case would point, in logic, that way.

Sooner or later someone will suggest that government should ‘step in’ and establish an appeals process. Then, sooner or later, someone will suggest that now the principle is established that a private bank’s procedure for selecting its clients should be regulated, the same principle should apply to other businesses and membership organisations. First they came for Coutts, and I said nothing… finally they’ll come for the Garrick.

Dame Alison’s ousting lifts the lid on banking’s wider moral pickle

When Dame Alison Rose was a frontrunner for chief executive of NatWest in 2019, I described her as ‘sensible’ and ‘unspun’ and said I hoped she’d get the job. That view was based partly on personal impression and partly on a prejudice of mine, expressed consistently since the 2008 crisis, that women often make better senior bankers than men, being less prone to macho risk-taking.

Rose has now yielded to political pressure and resigned over her role in the false reporting of the decision to ‘exit’ Nigel Farage as a customer of NatWest’s subsidiary, Coutts. But this column has never been in the business of following the baying crowd in hounding corporate chiefs from office. I did not agree with Boris Johnson’s demand, in the Daily Mail, that Rose’s head should roll if (as she finally admitted on Tuesday) she told the BBC that Farage had been binned for holding insufficient funds, rather than for the judgmental reasons revealed in a leaked Coutts report. I’m sorry she’s gone.

There’s no doubt, mind you, that the dame had spun herself – or been spun by Coutts boss Peter Flavel and his ‘head of client coverage’ Camilla Stowell, both of whose heads may have to roll with hers – into a five-star PR fiasco.

But it’s worth trying to understand the wider context. Underlying the Farage episode is the pickle in which all major banks find themselves as they contend with perceived reputational threats of all kinds and related anti-money-laundering issues, on top of pressures internal and external to preach the gospel of ‘inclusion’ and ‘purpose’.

Time was when London banks were full of loot deposited by dictators and oligarchs. Likewise, a global bank such as HSBC might exude high moral tone in the boardroom while its Mexican branch provided facilities for murderous drug cartels.

Reputational reverse nowadays – as in the case of Silicon Valley Bank, assailed by insolvency rumours – spreads so fast by social media that it can prove fatal within hours. As for NatWest, it operates under that name because of the terrible reputation it acquired, for vainglorious risk behaviour and harsh treatment of business customers, in its previous incarnation as RBS. It was Alison Rose who sought to complete the transformation by declaring the renamed bank to be ‘Purpose-led… helping people, families and businesses to thrive’.

None of which, you may tell me, has anything to do with the case of Coutts vs Farage. But my point is that banks today operate within a vast, creaking Heath Robinson construct of regulation and process designed to avoid reputational disasters. That includes mandatory annual reviews of ‘high-risk’ customers in politics and public life – who may not know, until a loan is refused or a card stopped, that they fall in that category. The whole paraphernalia is a hugely costly bureaucratic burden of the banks’ own making, because all of this was so badly done in the past. In the hands of over-zealous, ‘purpose-led’ middle-managers, it’s bound to go wrong. So it has for Coutts, whose business will suffer accordingly.

Kneejerk reaction

Meanwhile, the kneejerk reaction from No.10 was to call for new regulations requiring clear explanation and longer notice for bank account closures. But that will merely add to the pickle if they collide with existing ‘tipping off’ rules (under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002) that ban banks from giving closure information to customers suspected of financial wrongdoing. The National Crime Agency is reported to be lobbying against the ministerial proposals and I wouldn’t bet on them passing swiftly into law.

As for Dame Alison, the NatWest board’s declaration of ‘full confidence’ in her saved her bacon for less than 12 hours. But I still say her departure was unnecessary. NatWest needs a sensible helmsman. Farage had his media triumph. A systemic mess had been highlighted. Stand by now for multiple claims from ‘politically exposed persons’ and others of similar deceit, mishandling and in-discretion by their banks. This story will run and run.

Reality cheque

Boris Johnson’s column castigating Dame Alison contained a series of barbed rhetorical questions and one oblique reference to his days at Eton: ‘Coutts is no longer the self-styled posho bank used by kids at my school, who would buy turkey sandwiches from the tuck shop with 50p Coutts cheques.’ In those days, Eton High Street had a convenient Coutts branch where many pupils opened their first accounts. Was Johnson himself a sandwich-scoffing kid-customer? Might he perhaps have subsequently been exited, not as a reputational risk but for the well-known chaos of his personal finances? Perish the thought that I should encourage a further breach of client confidentiality, but I think we should be told.

Stupid game

On a lighter, related note, my call for nominations as to whose accounts we would cancel if this column were a bank produced such a colourful throng of personae non grata that Nigel Farage might have ended up as our only customer. Top of the list were highly paid but striking hospital consultants and Aslef train drivers, who would clearly need a fancier wealth management service than our modest venture could offer. Next came over-bonused Post Office managers, most Premiership footballers, ‘anyone associated with HS2’ and ‘anyone who’s ever appeared on Love Island’.

Among individual candidates, Gary Lineker, Sadiq Khan and (rather unkindly, I thought) Barbie led the voting. But I’m also grateful to one reader who reminded me of the danger of suggesting, even in jest, that it’s OK to constrain the rights of those we dislike or with whom we disagree, lest we should find the tide of intolerance turning on ourselves: ‘When you play stupid games, you win stupid prizes.’

What the French media can learn from the Farage banking scandal

Geoffroy Lejeune knows how Nigel Farage feels. Like the former Ukip leader turned TV host, Lejeune’s ‘values’ have made him persona non grata among France’s progressive elite. The 34-year-old journalist was last month appointed editor-in-chief of Journal du Dimanche (JDD), France’s only dedicated Sunday newspaper with a circulation of 140,000.

Newspaper staff were outraged. They downed tools, and have been striking now for five weeks. The papers’ journalists remain ‘more determined than ever’, they say, to continue their industrial action.

The real danger to democracy aren’t the likes of Lejeune or Farage, whatever their opinions may be

The problem is Lejeune’s politics. He is described as ‘far right’, and counts among his friends Marion Marechal. The niece of Marine Le Pen, she resigned as a National Front MP, as it then was, to set up a private university, before re-launching her political career as vice-president of Eric Zemmour’s Reconquest party. Lejeune threw his weight behind Zemmour in last year’s presidential election, endorsing the right-wing candidate via his editorship of Valeurs Actuelles.

Valeurs Actuelles has long been the bête noire of progressives in France: a weekly magazine that is a favourite among Catholics, retired military men and the Gallic equivalent of ‘outraged from Tunbridge Wells’. It was Valeurs Actuelles which, in 2021, published the open letter from a collection of ex-army officers warning that the country was sliding inexorably towards civil war.

Routinely described by its detractors as ‘far right’ – a term that these days is applied to anyone and anything that deviates from the progressives’ party line – the magazine is best described as the bible for the socially conservative. In 2019, Emmanuel Macron gave an interview to Valeurs Actuelles, justifying his decision by declaring that ‘it’s a very good publication, you have to read it to understand what the right thinks’. There was the predictable uproar from the bien pensants of Paris, who accused Macron of legitimatising the far right by airing his thoughts to the magazine over 12 pages.

The announcement that Lejeune would take over the editorship of JDD was certainly a surprise, given its reputation for bland centrism. But rather than wait and see what editorial changes he intended to implement, the staff walked out.

According to the paper’s journalists’ association, ’98 per cent of the newsroom are against and refuse to work’ with Lejeune, who is scheduled to take up his post on 1 August. The journalists’ strike is the longest of its kind in the media since a 28-month strike by the Le Parisien newspaper in the mid-1970s.

The industrial action is supported by Reporters Without Borders, which describes itself as an independent NGO that ‘works to defend press freedom’. It has called the appointment of Lejeune an ‘attack on journalistic values’. Christophe Deloire, the group’s secretary general praised ‘the determination and courage of the journalists of the JDD who refuse to be eaten alive’.

The hostility of the journalists, and the Paris progressive elite more broadly, is directed as much towards Lejeune’s new boss as at him. The JDD is part of the Lagardère group, which is in the process of being bought by Vincent Bolloré, described by one broadcaster as a ‘conservative Catholic’. He is also a billionaire. In recent years, Bolloré has acquired CNews (similar in editorial tone to GB News) and Europe 1, whose closest British equivalent is probably TalkRadio.

Both are routinely described as far right, an accusation that overlooks the origin of some of the broadcaster’s most talented presenters, such as Sonia Mabrouk and Christine Kelly, who was born in Guadeloupe. Mabrouk, who is of Tunisian descent, is an excellent interviewer whatever her guests’ political views, but, to some on the left, she is condemned because of her criticism of political Islam and American-style ‘identity politics’.

When Bolloré bought CNews and Europe 1 there were strikes, resignations and hand-wringing editorials in left-wing newspapers about the ‘threat to democracy’ posed by the new owner. Earlier this month Pap Ndiaye, in his capacity as education minister, endorsed this view, expressing his ‘concern’ at the influence of Bolloré in the French media and labelling CNews and Europe 1 as ‘clearly far right’.

This drew an indignant response from opposition MPs as well as the broadcasters’ journalists. CNews presenter Laurence Ferrari mocked Ndiaye for giving ‘lessons in democracy from his plush Paris salon, where state schools are good for others but not for his children’. (Shortly after Ndiaye was unveiled as education minister last year, it was revealed that he sends his children to one of Paris’s most elite private schools.)

Last week, Ndiaye was removed from his post in a government shuffle. Ostensibly it was because he was a very poor minister, but Emmanuel Macron would have noted his juvenile comments about parts of the French media.

Recently the president rebuked his prime minister, Elisabeth Borne, after she called Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party the ‘heir to Pétain’. Labelling the 13.2 million who voted for Le Pen in last year’s presidential election as ‘fascists’ was stupid, said Macron. Such tactics might have worked 30 years ago ‘but the fight against the far right no longer involves moral arguments’.

This reality has escaped the staff of the JDD who, just as Coutts did with Farage, ignore the fact that millions of people share the ‘values’ of Geoffroy Lejeune. In the narrow minds of these journalists, such values are immoral and the people who hold them should be ostracised.

The real danger to democracy aren’t the likes of Lejeune or Farage, whatever their opinions may be on Net Zero or mass immigration; rather it is the arrogance and intolerance of bankers, journalists and politicians who seek to silence those who don’t subscribe to the progressive world view.

Bridge | 29 July 2023

Imagination is often overlooked when discussing what makes a great bridge player. Ofc, being able to count to 13 helps, but imagination is different. It can’t be taught.

This hand, from the recent European Open Championships, features one of the most imaginative players around – Sweden’s brilliant but temperamental Peter Fredin – in the East seat. The knockout match was drawing to a close, and Peter’s team needed IMPs.

North’s 3♥️ bid was a splinter, and that was all South needed to hear before charging into 6♠️ via Blackwood. When it came around to Peter, he could see that – very likely – the only way to beat the slam would be for him to get a second-round Diamond ruff. If he could get partner to lead a Diamond, then – if said partner gained the lead with the ♠️A, or even the ♠️K – he could score a ruff. There was also the chance that partner held the ♦️Ace, and then the only way to get him to lead it was… Fredin doubled!

It could hardly have worked out better; his partner knew that it called for dummy’s first suit, so he placed the ♦️7 on the table. Declarer put up the Ace and finessed in Spades. Well, it could perhaps have worked out a tiny bit better: West won the Spade and played… the Ten of Clubs! An unhappy declarer had to finesse the Queen, and then a very happy declarer claimed the rest.

Can we blame West? Well, probably he should have continued Diamonds, but not everyone is imaginative! True to his nature, Peter calmly put his cards back in the board and said nothing. And if you believe that…

The problem with posh dog food

Having loaded the last sack of working dog food in Surrey into my car, I slammed the trolley back into the trolley park and shouted an expletive at no one in particular.

‘What have you done to your lovely country store?’ I thought about asking one of the sales assistants inside the newly revamped posh dog food shop that used to be a warehouse for horse feed and pet supplies. But the likelihood was they didn’t care.

I am making my exit from a county that has become one big dog park with a cycling track around it

Shiny displays with video presentations about the latest craze in frozen ‘fresh’ ready meals for dogs now took up most of the space, along with aisle upon aisle of extremely expensive pouches for pooches, those silly little cartons of allegedly organic dog food that I would have to feed in bulk to the point of bankruptcy to satisfy my lot.

I walked up and down the aisles for ages before finding three stray sacks of good old ‘Chudleys’, which still carries a royal warrant showing that it used to be By Appointment to the Queen. I would have King Charles down for the poochy pouches.

There was a Chudleys Working Crunch, an Original and a Salmon flavoured. They were running it down, obviously, on the basis that it was only £23 for a huge sack that is highly nutritious.

The spaniels’ preferred chicken and rice cartons were also in scant supply, no doubt because at £17.95 for 12 large servings it was judged to be way too much meat for the money.

The rest of the produce in this once great store was just the sort of nonsense the clueless classes would love to be charged any amount of money for, on the basis that the packaging told them how much they loved their dog.

It occurred to me that those who want frozen ‘fresh’ ready meals called Mitsy and Boo, or whatever, will be buying it online. Serves this lot right if they go bankrupt.

I looked around for horse feed but there was none that I could see. I stopped a store helper in a flashy uniform and she pointed to the far wall beyond the bird seed. Eventually it transpired that if I turned left at the furthest corner, by a completely un-signposted blank wall, I would happen upon a small store room round the back where, stacked to the ceiling because of the lack of space, were all the banished sacks of pony nuts, sugarbeet, oats and chaff that had formerly taken up most of the store.

I was in such a bad mood on seeing this that I slammed my trolley into a stack of chaff sacks, threw one on, then stormed off as much as one can storm while pushing a heavy load. Another helper in uniform – there was an army of them – started to recite some pre-learned script about how much he wanted to help me make my selection today, so I told him to chaff off.

‘Let me help you with that!’ beamed the checkout girl as I tried to push my trolley up to a long, high counter that was designed for someone putting down a couple of poochy pouches, a faux-fur dog cage poochy pad, and a hand-crafted pack of biodegradable pink poochy poo bags – 99p each or £4.30 for a pack of four.

She made an elaborate fuss of coming around the counter to scan my items with a hand-held device. And I made an elaborate fuss of not thanking her, standing there in stony silence, because it was entirely their decision not to have a low counter for scanning feed sacks from their seat.

I slammed my loyalty card down and asked for whatever was on it. ‘Er, there’s only £1.50 on that,’ she said. ‘I’ll take it,’ I said, ‘because I’m not coming back.’

And so into my car boot went the last sack of Chudleys Working Crunch in Surrey. A sad moment, as I make my exit from a county that has become one big dog park with a cycling track around it.

Surrey is also a frontier. How long suburbanisation takes to reach a more rural idyll near you is down to the amount of housing needed, and the amount of people wanting to work from home in a leafy place where they can keep a dog, get on a bike, and demand the farmers’ market goes vegan.

The fleeing suburbanites want to look at horses in fields. But because of the suburbanites, there are fewer and fewer places to keep horses, or ride them, or buy their food.

The once five-minute journey from my house to my horses’ field now takes 45 as the Highways Agency fells trees and tarmacs the heathland.

‘Improving your journey’, is how the signs describe it. Your journey to what?

Why I chose virtue over vice

Patmos

A funny thing happened on my way to this beautiful place, an island without druggies, nightclub creeps, clip joints or hookers. I stopped in Athens for about five hours in order to look over old haunts and just walk around places I’d known as a youth, when I

noticed something incredible: none of the youngsters I encountered were texting, nor were they glued to their mobiles and bumping into people. Sure, some were on their phones, but the majority of them were talking and gesticulating like normal humans used to do before the technology curse rained down on us.

Well, as they say, nothing lasts for ever, and once I was on Patmos friends informed me that what I had noticed in Athens was Alice in Wonderland stuff. Still, Patmos is wonderful, with very polite and friendly natives and no left-wing virtue signalling, as the place is full of ovens and gas hobs. The only thing missing is crime. Just Stop Oil cretins would be as welcome here as an atheist in a foxhole, but I’d love to see them come, as the solitary jail in Skala is empty, and the cops are feeling underemployed.

If you’re looking for action, however, head 85 miles to the southwest and you’ll find the biggest brothel this side of Las Vegas. It’s called Mykonos, and I used to love the place almost as much as I adored my mother. No longer. Even the magical embroidery of memory – the aching pathos of youthful romances and all-night partying – cannot erase the present horror of the place. Rich Gulf playboys, whose inability to attract women is known even in the cheapest dives of Ibiza, bring their own hookers on board their horror boats. There are non-stop vomit-inducing displays of wealth by unknown ‘billionaires’ and, worst of all, once proud Mykonians take in the freak show and do nothing about it. Money does talk.

And yet, why do I choose virtuous Patmos rather than the vice-ridden Mykonos? I am a sinner after all, and proud of it. That’s an easy one. Age has turned me into a goodie-goodie, plus the presence of a wife, two children and four grandchildren help to keep me northeast of temptation. Vice vs virtue is old stuff, and a certain Aristotle dealt with the conundrum in around 350 BC. He was Plato’s student until the latter’s death, and then gained further fame by developing a student from the north of Greece by the name of Alexander the Great.

Trust an American to turn Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics into a self-help work, a review of which was recently published in the New Bagel. The translation and abridgement of Aristotle’s work is by Susan Sauvé Meyer, and its title is just what hamburger-munching, TV commercial-watching Americans need: How to Flourish: An Ancient Guide to Living Well.