-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Dear Mary: how to leave a boring book club

Q. I am organising a funeral for a close relative and am puzzled that some people wish to attend the wake but not the service of committal at the crematorium. My view is that if you want to enjoy the wake, which will be a good party in a perfect country pub, then you should be willing to pay your respects first. Should I simply not inform these people in advance of the wake venue, since it is usual for this to be revealed only at the funeral on the order of service sheet?

– Name and address withheld

A. You could reply: ‘We haven’t quite sorted out the wake yet but if you haven’t got time for the whole thing do pop in at the end of the funeral to find out the venue.’ However, the general rule for funeral planning is the more the merrier, so just be straightforward and give them the details. This is not a time to mete out punishments to the unimaginative who, should they fail to attend the service first, will be the ones to miss out.

Q. One of my daughters is engaged and we are all thrilled about it. The young man in question is the son of someone about whose paternity there has always been debate. I happen to know the real bloodline but obviously don’t want to be drawn into vulgar gossip about it. What should I say when people ask me: ‘Oh you must tell us. Is his grandfather X or Y?’ – Name and address withheld

A. Why not baffle them by asking ‘Is the Pope a Catholic?’ This will make them think the answer is so settled that there is no further discussion to be had. They would be reluctant to press for further clarification as this would show them up as being out of the loop.

Q. A friend wants to give up going to her book club because it bores her and they always veto her choices. The others also take the books far too seriously for her liking. This friend has been a member for 20 years – how can she stop going without offending, other than moving to the country?

– P.P., London NW3

A. Your friend must sit down immediately and type out 1,000 words of a story she can make up as she goes along. Next time she goes along to the book club she can reveal the exciting news that she has begun to write a novel herself. However, the bad news is that she is going to have to stop going to their book club meetings. She has found that she has too vivid an ability to conjure up in her mind the discouraging judgments of critics if the novel is ever finished and published. Consequently her progress is being impeded by self-consciousness and so she is sadly having to bow out until the novel is finally completed.

Write to Dear Mary at dearmary@spectator.co.uk

What I learned from being debanked

My own debanking story concerns a card rather than a bank account. Not the same degree of inconvenience as Nigel Farage, but a similarly telling insight into modern administrative culture. I feel awkward writing this, because in the 30 years I have used American Express, including an enjoyable decade when I also worked for the brand as a copywriter, few companies have impressed me more. They are unfailingly courteous and responsive. On many occasions, such as when arriving at an airport to discover I had to pay £4,000 for an unratified airline ticket, my card has been invaluable; I willingly follow their advice not to leave home without it.

But one evening last year Amex didn’t do nicely. There’s a special feeling to having a Platinum card declined. In Monaco or Palm Beach it might be fashionably raffish; this was at McDonald’s in Stratford-upon-Avon.

You must endlessly justify your productivity to the finance department, but how productive is your finance department? Nobody knows

Some months earlier, to comply with ‘anti-terrorism and money-laundering legislation’, they’d asked me for photographs of the passports of all cardholders on my account. I’d dutifully uploaded this information for my wife and daughters but not for my father, who is in his nineties, does not have a passport, lives 160 miles away and has no known ties to al Qaeda or the ’Ndrangheta. I naively assumed that since it is uncommon for a criminal organisation to confine its financial activities to fortnightly visits to M&S Simply Foods, this wouldn’t matter. I was wrong. I then missed the single email I was sent informing me of their intention to cancel all cards on my account for ever.

The person on the phone clearly thought the decision was nuts but was powerless to act. It was like a posher version of the phone call in Goodfellas: ‘This is Vinny. We had a problem. And we couldn’t do nuttin’ about it.’ I was an unmade man.

‘What has happened is your compliance department is running your business,’ I said. ‘If it’s worth sending 20 letters by post to gain a customer, it’s worth sending two letters by post to avoid losing a customer.’ A month later my card was quietly reinstated.

Why would a normally sane company do something so peremptorily stupid? Well, it’s called Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy and it applies everywhere. Pournelle’s Law states that ‘in any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals that the bureaucracy is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence or are eliminated entirely’. Bureaucracies hence grow in a way analogous to cancers, which occur whenever the reproductive interests of a tumour contrive to diverge from the interests of the organism sustaining it.

We often see this as just a public sector problem. Trust me, it isn’t. Any administrative function allowed to ride roughshod over the people delivering value to the citizen, customer, patient or student is at permanent risk of growing uncontrollably or else metastasizing into something harmful. No one actually serving Coutts’s customers would have time to write a 40-page dossier on Nigel Farage – they’d be too busy working. But Farage’s bank manager would have no sway over the decision of the commissariat. Where will this end?

Such departments should receive more scrutiny than the people who perform the core functions of a business. Instead they evade scrutiny by the cunning act of setting themselves up as arbiters over the people who do the actual work. You must endlessly justify your productivity to the finance department, but how productive is your finance department? Nobody knows. And where did all these jobs come from suddenly? If there is one economic statistic that terrifies me, it is the appallingly low rate of middle-class unemployment.

Putin tries to turn Africa against the West

After Vladimir Putin’s speech at the Brics global summit in South Africa, there can be no doubt that the Russian president has set his sights set on wooing the nations of Africa. In an effort to present Russia as a cooperative ally to, and leader of, the Brics bloc (currently made up of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, but with 40 more aspiring members) Vladimir Putin pinned the blame on the West’s ‘illegal sanctions regime’ for the global food supply problems experienced by many countries in the wake of his invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian president acknowledged the grain issue was ‘hurting the most vulnerable poor countries first’, but suggested that ‘Russia is deliberately obstructed in the supply of grain and fertilisers abroad and at the same time [the West] are hypocritically accusing us of the current crisis situation on the world market’.

Putin is looking to capitalise on the power imbalance the collapse of the Black Sea grain deal created

That the grain shortages have been caused by Russia’s refusal to extend a deal allowing the export of Ukrainian grain via the Black Sea – which has hit countries in Africa in particular – was something he, unsurprisingly, did not mention.

As Putin’s speech made clear, he has been on the charm offensive in Africa for some time. Last year, he revealed, trade between Russia and African states amounted to the equivalent of £5.3 billion, while bilateral trade between January and June of this year increased by 60 per cent. Now he is looking to capitalise further on the power imbalance the collapse of the Black Sea grain deal created.

‘Our country is and will continue to be a responsible supplier of food to the African continent,’ Putin pledged, promising that Russia would send free grain to six African countries. The Russian president had originally made this promise at the Russia-Africa summit he hosted in St Petersburg last month, saying Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Mali, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Eritrea would be provided with up to 50,000 tonnes of grain in the coming months.

Russia is capable, he said, of ‘replacing Ukrainian grain’, with 11.5 million tonnes exported to Africa in 2022 and a further ten tonnes sent in the first six months of 2023 alone. More would come as Russia apparently expects an ‘excellent harvest this year’. How much of last year’s exports came from the 400,000 tonnes of grain the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence claims Russia has stolen from the country since the beginning of the invasion isn’t clear.

Now that he is increasingly isolated on the world stage, Putin needs the cooperation of African states to maintain the facade of his position as a global leader. His speech at the summit was peppered with language which aimed to pit those countries against the West.

More than 70 per cent of the grain exported from Ukraine, Putin claimed, went to ‘countries with high and upper middle income levels, including primarily the European Union’. His message to the attendees was obvious: the West doesn’t care about the poorest countries in Africa.

The Brics nations now needed to cooperate to represent the interests of the ‘global majority’, Putin said. He emphasised that the bloc is forecast to surpass the G7 by 1.5 per cent this year when it comes to purchasing power.

Some of the punch was taken out of Putin’s address due to reported technical difficulties that warped the recording of the president’s voice, to the confusion of the attending audience. Putin recorded his speech after refusing to attend the summit in person over fears he would be arrested in South Africa for war crimes in Ukraine. This is because South Africa is a signatory of the International Criminal Court which in March issued an arrest warrant for the Russian president over the abduction of Ukrainian children. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov is representing him at the summit instead.

In a sign that the arrest warrant has bruised his ego, Putin couldn’t quite bring himself to admit this was the reason for his absence – despite it being the elephant in the room. Contradicting his efforts to intensify relations with the bloc, last month he downplayed his absence, saying his presence in South Africa was not ‘more important than my presence here, in Russia.’

Putin’s path to influencing the Brics bloc may not be as straightforward as he might hope, with some of the group’s leaders expressing hesitancy at being pitted as new competition for the West. Just yesterday Brazil’s president Lula said that ‘we do not want to be a counterpoint to the G7, G20 or the United States’.

With the summit due to run until tomorrow, however, there is still time for Lavrov to work the room and make progress on the president’s behalf in strengthening Russia’s grip over the bloc. Putin’s virtual charm offensive may yet pay off.

The Battle for Britain | 26 August 2023

The appalling hypocrisy of Peter Wilby

According to the ancient proverb, if you sit by the river for long enough you will see the body of your enemy float by. That happened to me earlier this week when I discovered the fate of Peter Wilby, a former editor of the New Statesman and the Independent on Sunday. In 2018, when I was forced to resign from a government job over old tweets, Wilby wrote an article saying my public humiliation had come as no surprise to him. Apparently, I’d made a career out of ‘denigrating women, homosexuals, disabled people, ethnic minorities and anybody on benefits’, and ‘disgraced’ the memory of my dead father. ‘At one stage he was more or less addicted to both alcohol and pornography,’ he said.

That piece cut me to the quick. If you’re in the process of being cancelled – I ended up having to step down from four more positions that year – you read all your press coverage, desperately hoping someone is going to stick up for you. When I saw my name in the headline of Peter’s diary column in the New Statesman, my spirits soared. In addition to publishing various pieces of mine over the years, he had written a sympathetic article in the Guardian about my efforts to set up a free school. At last, I thought, a senior media figure who’s going to give me a fair hearing. So reading his little sermon was a bitter blow. It wasn’t just because I liked and respected Peter. It was the fact he had known my father, who died in 2002. It was like receiving a judgment from beyond the grave, delivered by proxy. I had ‘disgraced’ him.

How could this liberal journalist who denounced right-wing sinners from his pulpit have harboured such a shameful secret?

You can imagine my astonishment, therefore, when I read last Saturday’s Times: ‘Peter Wilby: former Independent on Sunday editor sentenced over child sex images.’ The article said that 167 indecent images of children were found on his computer, 22 of which were ‘the most serious kind’. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to ten months in prison, suspended for two years. In addition to having to carry out 40 hours of rehabilitation, he is subject to a ten-year sexual harm prevention order and has been placed on the sex offenders register for five years. According to Adam Sprague, of the National Crime Agency: ‘The material accessed by Wilby and recovered from his computer showed real children being cruelly and sexually abused.’

My initial reaction was one of complete bewilderment. How could this eminent liberal journalist who regularly denounced right-wing sinners from his pulpit in the left-wing media have been harbouring such a shameful secret? When writing about the mote in my eye, why didn’t he pause to examine the beam in his own? It seemed extraordinary that he could have thundered away with such moral righteousness on the very same keyboard he’d been using to access child pornography. I was reminded of Christopher Hitchens’s famous quote about the hypocrisy of conservatives who condemn homosexuality: ‘Whenever I hear some bigmouth in Washington or the Christian heartland banging on about the evils of sodomy or whatever, I mentally enter his name in my notebook and contentedly set my watch. Sooner rather than later, he will be discovered down on his weary and well-worn old knees in some dreary motel or latrine, with an expired Visa card, having tried to pay well over the odds to be peed upon by some Apache transvestite.’

Perhaps the reason for my surprise is because at some level I still take the left’s virtue-signalling at face value. As Hitchens says, the evangelical preacher who turns out to be a sexual degenerate is a stock character in the pantomime of public life. But for secular holy men like Wilby to have feet of clay always comes as a shock. Not because it’s such a rarity – it isn’t – but because of their elevated social status. As far as the metropolitan elite is concerned, these are the people we’re supposed to take moral instruction from. When they tell us we should have voted Remain or have a moral duty to welcome illegal immigrants, they’re not just demonstrating their superior knowledge but their status as semi-official custodians of public decency.

But in reality this is no more a guarantee of personal probity than a dog collar. On the contrary, these finger-wagging Puritans are often guilty of projection, raging in high dudgeon at the shortcomings of others as an indirect way of expressing their self-disgust. Is that why Peter accused me of being addicted to pornography? When he said I’d disgraced my father, was he thinking of his own father’s reaction if his behaviour ever came to light? I remember feeling a red-hot burning shame when I read Peter’s condemnation of me. Next time, I’ll know better.

Should trans women be banned from women’s chess?

The arguments for keeping trans women from participating in women’s sport are well rehearsed. As the former Olympic swimmer Sharron Davies wrote in this magazine in June, the simple truth is that men on average run faster, jump higher and are stronger than women. Their biology gives them irreversible advantages.

Even the world of chess has been pulled into the debate. Last week, the International Chess Federation banned trans women from participating in women’s matches. The English Chess Federation, on the other hand, refuses to exclude trans women. On first inspection, the decision to ban makes no sense. After all, the usual arguments of unfair physical advantages in women’s games don’t hold water. However, the truth is that differences between men and women go far beyond the physical. Cognitive differences also exist.

Differences between men and women go far beyond the physical. Cognitive differences also exist

Exactly 40 years ago, in Frames of Mind: the Theory of Multiple Intelligences, the psychologist Howard Gardner proposed eight different types of intelligence: musical–rhythmic, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic. Skilled chess players, as Gardner noted, score high in both logical-mathematical and spatial intelligences.

Logical-mathematical intelligence involves the ability to identify logical or numerical patterns and manipulate abstract information. On average, and I stress the word average, men tend to score higher in this type of intelligence. Men also tend to score higher on visuospatial abilities. In chess, like any other sport, the ability to interpret visual information and respond with an appropriate motor response is crucial. Top chess players have high levels of visual-spatial intelligence. This ability to hold the world visually in the mind is what separates a truly great chess player from a good one.

A 2019 study carried out by Chinese academics showed that males tended to outperform females ‘in both large-scale and small-scale spatial ability’. Another study concluded that ‘a high level of general intelligence and of spatial ability are necessary to achieve a high standard of play in chess’. Contrary to popular belief, patriarchal social limitations aren’t to blame for men’s domination in chess. In fact, as the authors of another study from the University of Mons noted, ‘high spatial ability of these young chess players suggested by the high performance IQs may go some way towards explaining why males tend to be more numerous than females among high-standard chess players’. Some research suggests that adult males have an advantage of somewhere between four and six points over adult females. A controversial point, I know. But please don’t shoot the messenger.

Chess is a game of recognition. Again, when it comes to recognition – pattern recognition, to be specific, one of the most important aspects involved in good chess play – males tend to score higher than females.

It might seem odd to discuss the role testosterone, the so-called ‘toxic’ hormone, plays in chess – but that’s only because testosterone is misunderstood. Although it’s true that testosterone plays a monumental role in regulating sexual desire and sexual function, it also plays a significant role in cognition; in other words, helping you think. There is a strong association between testosterone and visuospatial ability. Moreover, testosterone helps fuel competitive behaviour.

Adequate levels of testosterone have been shown to positively predict better performance in endurance-related activities. A game of chess can go on for many hours – three, four, even five. Persistence is key. Testosterone also helps memory and focus. Adult males typically have between 265 and 923 nanograms per decilitre of testosterone; adult females, on the other hand, somewhere between 15 and 70.

David C. Geary, a cognitive scientist and evolutionary psychologist who has spent most of his professional career studying the biological bases of sex differences, echoes my visuospatial point. ‘Although trans women’s physical advantages will not give them an advantage in women’s chess competitions, other factors might,’ he tells me. ‘Chess has a visuospatial component to it, in terms of learning common chess configurations and recalling them during games, which typically favours boys and men. At least some components of visuospatial abilities are related to prenatal and early postnatal exposure to sex hormones. Thus, suppressing circulating testosterone won’t negate a likely advantage of trans women in this area.’

Geary makes another point: ‘Boys and men are much more likely to become status- focused than girls and women, and with its ranking system chess seems well suited to trigger this competitive focus. The sex difference here is influenced by a combination of prenatal and pubertal hormones and will likely give trans women an advantage. Here, the advantage will result from more practice and engagement in many competitions that in turn will result in higher rankings.’

Which brings us back to the International Chess Federation’s decision. As is clear to see, it’s not transphobic. It is logical. The English Chess Federation should take note.

Are whole life orders becoming more common?

Bank on it

Does the August bank holiday actually celebrate anything?

– When bank holidays were first established in 1871, the August bank holiday fell at the beginning of the month, allegedly because it was an important week for cricket in Yorkshire, the home county of MP Sir John Lubbock, who introduced the parliamentary act creating bank holidays.

– It was moved to the Monday after the last Saturday in August as an experiment in 1965, largely because early August coincided with the annual factory closure, and many workers were on holiday then anyway.

– In 1968 and 1969 the holiday fell in September, so in 1971 it was fixed as the last Monday in August. Except, that is, in Scotland, where it remains in early August.

Complete sentences

The former nurse Lucy Letby was handed a whole life order. Are these becoming more common? Total number of prisoners serving life vs number serving whole life orders:

Life (inc WLOs) / WLO

2012 7,676 / 45

2013 7,564 / 43

2014 7,468 / 48

2015 7,439 / 51

2016 7,361 / 53

2017 7,247 / 59

2018 7,117 / 63

2019 7,027 / 63

2020 6,985 / 63

2021 6,963 / 60

2022 7,084 / 65

Source: Ministry of Justice

Mother countries

Some 30.3% of babies born last year were to mothers who were themselves born outside the UK, up from 28.8% in 2021. In which countries were the mothers born?

India 17,745

Pakistan 16,654

Romania 5,518

Poland 11,107

Nigeria 8,458

Bangladesh 7,007

Afghanistan 3,875

Albania 3,515

US 3,200

Germany 3,154

Source: Office for National Statistics

Profits of doom

Are UK companies becoming more or less profitable? Net rate of return for non-financial corporations:

1998 13.8%

2000 11.3%

2002 10.7%

2004 11.1%

2006 10.9%

2008 10.9%

2010 10.4%

2012 10.9%

2014 11.9%

2016 11%

2018 10.1%

2020 9.5%

2022 10%

Source: ONS

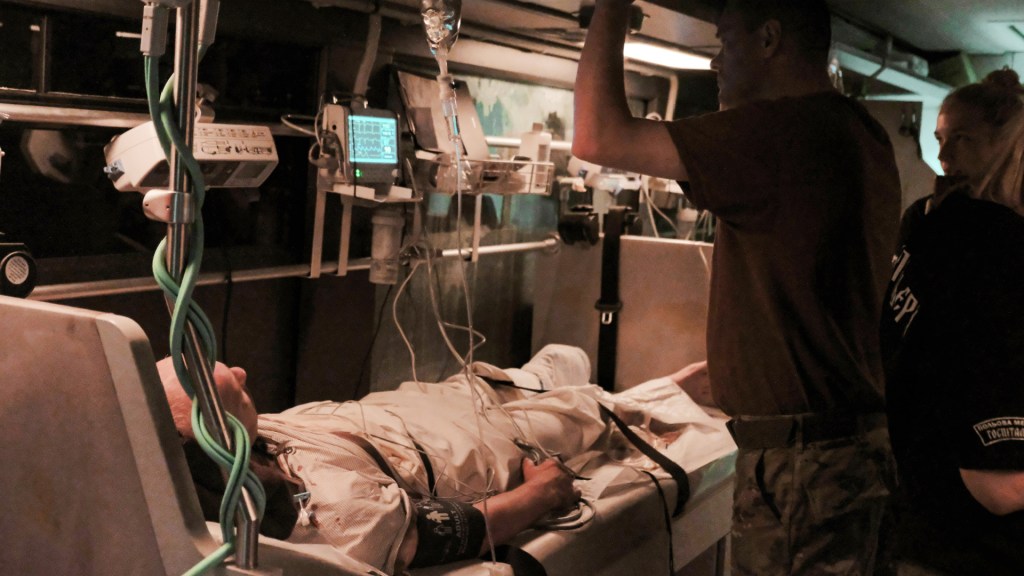

Ukraine’s real killing fields: An investigation into the war’s first aid crisis

Donetsk

It’s past midnight and I am standing in silence with the crew of a military ambulance on the edge of the Donetsk region. The village is dark to avoid attracting the attention of Russian drones. The paramedics move with quiet determination, lifting blood-soaked stretchers and ferrying moaning, injured soldiers from one vehicle to the next. I see a wounded man with bandages where his legs used to be. His severed limb sits next to him in a bag.

There are no figures for how many Ukrainians have been maimed in this war. Nor are there proper figures for the dead. Kyiv doesn’t give body counts, saying only that Ukrainian casualties are ‘ten times less’ than Russia’s. Keeping the numbers secret prevents scrutiny. The US estimates that at least 17,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed in action. Another official told the New York Times the number could be as high as 70,000.

Many of those lost in the war die while they are being moved back to safety rather than on the front line

I am told by those working here that many of those lost in the war die while they are being moved back to safety rather than on the front line. The long journeys to hospital, sometimes up to ten hours, can be lethal, and the availability of adequate first aid is the difference between life and death.

Ukrainians believed that the very best care would be available for their soldiers. But the stark truth is emerging: soldiers are dying in their hundreds or even thousands due to poor medical provision. The problem is being ignored by the military hierarchy, whose focus is on sourcing weapons and pushing the counteroffensive rather than prioritising injured fighters.

Word of this has spread, and Ukrainians are responding by donating to independent medical units serving on the front line. I’m with one such group, the Hospitallers. It is a Ukrainian volunteer medical battalion that works closely with frontline troops.

I see the Hospitallers take in six injured soldiers who have been handed over to them by combat medics. These men were hurt about five hours ago; it then takes four more hours to get them to the hospital in Dnipro. ‘This is a fight for life. Our task is to keep them going until they reach the hospital, to help them survive. Once there, they will receive more advanced medical assistance,’ explains Toronto, 28, a paramedic. I ask him who would be rescuing these soldiers were it not for the Hospitallers’ volunteers. ‘Nobody,’ he replies.

Ukraine has mobilised more than half a million people into the military, and it badly needs tanks and aircraft for the war effort. This message is the one Ukraine’s allies have received: give us the tools, and we will finish the job. But there is also a far less publicised but no less urgent need for medical aid, including for vehicles to transport the injured to hospitals.

The bureaucracy surrounding the first aid process is to blame for many of the shortages. If a hospital vehicle is destroyed by enemy fire, it is not registered as being out of action until an official investigation has been carried out. This can take up to six months. Until the paperwork is done, the vehicle stays on the books and is not replaced. It’s common to find military brigades that have lost 80 per cent of their evacuation transport, but that can’t be resupplied because the official report does not acknowledge that the vehicles have been destroyed.

As a result, volunteers are taking matters into their own hands. I’m shown around Avstriyka, a £100,000 mobile hospital bus, funded by donations. It is a unique unit which can carry up to 33 soldiers, with six on stretchers.

One of the paramedics I meet is an American volunteer, Victor Miller, 34, who served in the US navy and last year joined Hospitallers. ‘If you have it within yourself to go and do something and help people, you should do it,’ he tells me. ‘It’s only a matter of time till the war moves past Ukraine.’ He talks about the shortage of medics and says far fewer foreign volunteers are there now than there were last year: ‘We had 50. Now we have fewer than ten foreign paramedics.’

Another problem is that corruption has been allowed to flourish. One example is the proliferation of low-quality medical supplies being used to treat Ukrainian soldiers. A few weeks ago Volodymyr Prudnikov, the head of Ukraine’s Medical Forces Command’s procurement department, was accused of supplying 11,000 uncertified Chinese tactical medical kits to the front line. It is alleged that Prudnikov awarded £1.5 million-worth of contracts to a company co-founded by his daughter-in-law and was attempting to pass the Chinese kits off as Nato standard. He has been fired and now faces an investigation, but has yet to comment.

It is just one example of the profiteering that is needlessly risking the lives of soldiers. Another example of corruption occurred last year in Lviv, where 10,000 tactical first aid kits worth £700,000 were sent by American volunteers and then mysteriously disappeared. It was recently reported that the US is investigating this case.

‘The military leadership can refuse to accept supplies because they are fully stocked with low-quality alternatives’

More questions arise when it comes to the contents of the first aid kits that do make it to the front line. Tourniquets are perhaps the most-needed first aid tool, particularly when the evacuation process is prolonged. But if tourniquets are badly made, they can be lethal. There have been complaints from the front line about Chinese-made tourniquets that either gradually lose pressure or come apart, leading to renewed bleeding with fatal consequences. A Chinese tourniquet costs just £2, while a Ukrainian ‘Sich’ tourniquet is £15. An authentic American CAT tourniquet comes in at around £35.

Investing in decent tourniquets is money well spent. The medics I speak to say that two-thirds of Ukrainian soldiers die from blood loss. I meet Bilka, 24, a medic in the 243rd Territorial Defence Battalion, who has just returned from Bakhmut. She explains what happens to the injured person on the front line: ‘You have to drag a person with your hands approximately three to five kilometres. You can’t drive there even in armoured vehicles because of the heavy shellings and mines.’

Medics, she says, try to avoid using the official first aid supplies issued to them, because of the admin that is involved. Each component of a government-issued medical kit must be accounted for, including equipment that is obviously sub-standard. ‘If a drug has expired, the write-off procedure is so difficult that it is easier to record that it has been destroyed by fire,’ she says.

Some medical staff are funding equipment with contributions from their own salaries even though the average doctor in Ukraine only earns about £300 a month and a nurse half that sum. The situation has become so bad recently that medics at one hospital in Dnipro, which was overloaded with injured men from the front line, had to raise money to buy antibiotics, analgesics, gauze and even gloves needed for treatments. Meanwhile some £3 billion a month is spent on warfare.

I also talked to Yuri Kubrushko, the co-founder of the Leleka Foundation, another medical charity. He says that the surprise full-scale invasion last year was always going to mean there would be a shortfall of proper medical supplies. But 18 months later, the situation still hasn’t improved. ‘The problem with providing equipment to combat medics is being hushed up as if it doesn’t exist,’ he tells me. ‘The military leadership can even refuse to accept new medical supplies because they are fully stocked with low-quality alternatives. They think that asking charities for help would undermine the authority and reputation of the armed forces.’

When it emerged that 15 per cent of medical supplies donated by the West last year had passed their expiry date, it led to public outcry and criminal prosecutions. Officials from Ukraine’s Medical Forces responded by saying they would inspect all medical kit in the army. But no guidelines or standards for these inspections have been issued. Senior officials in Kyiv do not seem prepared to complain, or bothered enough to do thorough checks before sending the first aid kits they receive on to the front line.

‘The leadership of the old establishment doesn’t truly understand what is wrong,’ says Kubrushko. Inspections are no use if the people commissioned for the task have no idea what to look out for. ‘They won’t suddenly become tactical medicine specialists just because an order came from above.’ As a result, reports are tinkered with, which in turn distorts the statistics on how much medical aid is required. Why should Ukraine ask for more medical equipment, when officially the shortage doesn’t really exist?

Tetyana Ostashchenko, the commander of Ukraine’s Medical Forces, has said in an interview that the problems Ukraine faces have no precedence in modern times. No western country has experienced what Ukraine is going through. Two weeks ago, Ostashchenko was given a final warning and ordered to undertake an inspection of frontline equipment, but the promised report has yet to materialise. ‘If the criticism is constructive, then of course our reaction will be immediate,’ she says.

To compound the problem, medics in Ukraine are also expected to fight. ‘You can’t sit and say, “I’m a medic, I won’t shoot.” Everyone shoots. Only after the fighting is carried out, then you provide the first aid,’ says Gurman, 27, a senior combat medic with the 243rd Territorial Defence Battalion.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, combat medics sent out to rescue injured soldiers under Russian fire often lack both the training and the authority to deliver aid. Some have a medical background, but most must learn in the field, usually at the front line. A senior combat medic will teach junior members. In the whole of Ukraine, only one military base is capable of providing an official qualification for a ‘junior medical personnel’. That base turns out 300 medical cadets a month, but to allow for one medic for every 30 soldiers, Ukraine needs to train at least 15,000 combat medics. There are various private training centres which devise methods as they see fit.

The UK has so far trained 17,000 Ukrainian soldiers since last February, some of whom are medics. But all too often they are used to working with a standard of kit that is unavailable in Ukraine, and the training is not tailored to the war that is being fought. Gurman was trained in York. He tells me about the arguments he has subsequently had with his instructors. ‘The medical course is focused on gunshot wounds. But in Ukraine, soldiers are being blown apart. You need to piece a whole person together,’ he says.

Russian attacks target Ukrainian medics as a priority, he adds. ‘If Volodymyr Zelensky was in a car and we were sitting in a car next to his, they would hit us first, because we save lives.’ Russian forces use drones to track medical vehicles and then fire at them. Ukraine’s military medical institutions have seen over 1,000 attacks since last year’s invasion.

Russia is, of course, responsible for the lives lost in this war. But it seems undeniable that the Ukrainian authorities’ neglect of the medical necessities is leading to a far higher death toll.

It’s time to get on with the Indian trade deal

The trade secretary Kemi Badenoch will be in India this week for a meeting of G20 trade ministers. The Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will be visiting the country in September. With so many ministers on hand, it might seem the perfect moment to unveil the long-awaited UK-India trade deal. After all, the former PM Boris Johnson at one point promised to get it wrapped up before Diwali in the autumn of 2022, although as so often he over-promised and under-delivered. Even so, the dithering is getting more and more alarming. A trade deal with India is now the big prize of Brexit – and should be wrapped up without delay.

A trade deal with India is now the big prize of Brexit – and should be wrapped up without delay

Trade deals with Australia and New Zealand are all very well. But in reality, it will be a deal with India that will prove far more significant in the long run. There are three reasons for that. First, a deal with the United States now looks to be off the table for the foreseeable future, and that leaves India as the most significant partner. It has already overtaken the UK by total GDP (although that is not much of an achievement anymore) and it is expected to overtake Germany in 2027 and Japan in 2029 to become the third largest economy in the world.

Next, it will cement the UK’s critical pivot towards the Pacific that started when we signed up to the CPTPP that stretches across most of Asia and much of South America. Hardcore Europhiles may regret it, but the Asia-Pacific region is growing far more quickly, and is a far more lucrative market for the mix of legal, financial and consulting services that the UK has become very good at exporting. With India added as well, Britain will have the chance to embed itself deeply into the region’s commercial infrastructure. Finally, there are already well-established family and historic links between the two countries. Plenty of major British companies already have a major presence in India, and vice-versa, and with lower tariffs, easier movement of executives and staff and common trading links, that can only grow.

The trouble is, there are worrying signs that it is getting delayed. Officials have been briefing that there are still plenty of issues to be resolved, and the deadline is slipping and slipping.

The PM will be in India next month. He should use the opportunity to overcome whatever obstacles still remain, and get the deal ready to sign. It is by far the most significant prize of Brexit – and if it does get agreed it may well prove to be the greatest legacy of what will almost certainly be a relatively short stretch in No. 10.

In defence of budget airlines

I have a memory picture of an urban highway in Shenzen, southern China. Recently built, with abundant flowering shrubs planted along its central reservation, it was lined as far as the eye could see by uncountable apartment towers, many of them unfinished. This was 2009 and it was my first glimpse of the debt-fuelled property bonanza that had begun to grip the Chinese economy – alongside the export-led manufacturing boom that was also plainly visible, thanks to satellite maps of the vast agglomeration of factories surrounding the new-rich residential areas.

It’s easy to be a permanent bear in any market, because history tells us they all come crashing down in the end. But my own long-term negativity towards China prompts me to nod knowingly at news that the property giant Evergrande, which has current projects in 280 Chinese cities, has filed for US bankruptcy protection as part of a restructuring of $32 billion of offshore debts; that shares in the even larger Country Garden group have plummeted after it failed to meet bond payments; and that companies accounting for some 40 per cent of Chinese home sales have defaulted in the past two years.

Meanwhile, China’s exports were down 14.5 per cent year-on-year last month, its domestic consumers are as nervous as its unpaid bondholders are angry – and its banking industry is certainly more fragile than published balance sheets might suggest. GDP growth that has averaged almost 9 per cent per annum since 1989 may fall below 5 per cent this year. Official interest rates have been cut as a stimulus, but no one believes Beijing’s autocrats can intervene, manipulate or lie on the scale required to shore up the entire tottering $20 trillion economic colossus.

In my first column of this year, I wrote that if there’s a black swan – a shock that changes everything – out there somewhere, I put the chance of it coming from China at 60 per cent. If it’s now floating towards us from downtown Shenzen, there’s no consolation in saying I’m pretty sure I anticipated it all those years ago.

Roux the day

Is something rotten in the state of Mayfair’s Upper Brook Street? At No. 18, Odey Asset Management imploded after allegations of sexual impropriety against its founder, Crispin Odey. At No. 43, Le Gavroche – the Roux family restaurant that brought haute cuisine to London and was much frequented by the gourmand Odey himself – has announced it will close when its lease ends early next year. I don’t suppose the loss of the Odey expense account is the entire reason for the closure, but it’s interesting to reflect on the wider Roux footprint in London’s financial scene.

Besides feeding the fat cats at Le Gavroche in Mayfair (and previously in Lower Sloane Street), Albert and Michel Roux created Le Poulbot in Cheapside, where the £5 set lunch made it a regular hangout for my cohort of young bankers toiling across the road at Schroders. It was named ‘probably the best in the City’ by the New York Times in a 1984 article headed ‘Britain’s restaurant revolution’ that garlanded the brothers’ expanding portfolio.

In an era when deep-pocketed American firms were crowding into the Square Mile, Le Poulbot also became a haunt of headhunters trying to poach posh Brits to add tone (or so we imagined) to the rough milieu of New York-style trading floors. ‘I’ve had an offer from Goldman Sachs,’ a double-barrelled colleague whispered one day. ‘Goldman who?’ I replied. Those were the days.

Then there was what the Roux brothers called their ‘fraternité’ with the globe-trotting financier Michael von Clemm, who chaired their business while also leading Credit Suisse First Boston and later Merrill Lynch. It was also in 1984 that von Clemm ventured east to the semi-derelict Canary Wharf in search of industrial space for a Roux catering venture – and conceived instead the idea of the vast office development that was eventually brought to completion by the Reichmann family from Canada.

As office needs shrink and anchor tenants such as HSBC move out, Canary Wharf itself may now slowly go the way of Odey and Le Gavroche – an ironic footnote to this Roux-flavoured ramble round London being that the ideal premises for a serious downsizer from Docklands is surely an elegant town house in Upper Brook Street.

From the departure lounge

Also in my first column of January, I see I praised Ryanair: ‘My cheap New Year flight to France, booked in seconds, was bang on time and full to the last seat.’ That column was filed (like this one) from the departure lounge on the return leg. But moments after I pressed ‘send’, we were told that ‘fog’ (actually thin mist) had forced our aircraft to divert to another airport, to which we would be bussed. No buses appeared and no more announcements followed; several hours later a plane arrived to collect us.

‘Typical bloody Ryanair,’ muttered fellow passengers. And with the end of the holiday season in sight, that sentiment was echoed this week in media comment about the way the add-on pricing systems used by the likes of easyJet and Wizz Air as well as Ryanair – for luggage, seat allocations, booking changes and the rest – generate far higher fares than first advertised and sometimes higher even than British Airways.

To which I say piffle. You only have to book once to learn how to play the system: buy the security fast track but not the pointless ‘priority boarding’; pick the cheapest aisle seat; never check a bag in if you can avoid it; never buy the insurance offer or the ‘meal deals’. The low-cost airline model is perhaps the greatest modern advance in consumer choice: it smashed state carriers’ cartels, daily defeats the bolsheviks of European air traffic control, takes us to unheard-of -destinations at fares that are still cheaper than long-distance UK train journeys – and sets a benchmark for brutal efficiency that every other business sector would do well to aim for.

Of course it also sometimes goes wrong. If it does so today, I’ll tell you next week.

Letters: Hollywood owners have ruined Wrexham FC

Wild abandon

Sir: As upsetting and pointless as is the National Trust’s cancelling of the fishing lease on the River Test at Mottisfont Abbey (Letters, 19 August), it is all of a piece with the way the National Trust is going. On the 13,000-acre Wallington Estate in Northumberland, the Trust has recently spent a small fortune elaborately fencing off 50 acres to release beavers on one of the two farms they have recently taken out of agricultural production. They trumpet their intention to create ‘Wild Wallington’ by abandoning it to nature and planting trees on as much of the estate’s farmland as they can. The farms at Wallington were wrested from bleak and barren heath and moorland in the 18th century by the vision and riches of Sir Walter Blackett, who bought vast areas and turned it into some of the most fertile farmland in England. At the same time as China announces its intention to bring more land into cultivation to be self-sufficient in food, the short-sighted NT are hellbent on famine.

Philip Walling

Scots Gap, Northumberland

Nearest and dearest

Sir: For many years now I have supported Halesowen Town as they are the nearest team to me. I hardly ever miss a home game and try to get to as many away fixtures as I can (‘Leagues apart’, 19 August). The beauty of non-League football is to be able to sit or stand where you like and cheer for your own team without any ill will from opposition supporters. It’s very rare for any trouble to kick off, and there is the added bonus that you can have a drink and take it on the terraces with you. Being in close proximity to the pitch also means you can enjoy ‘banter’ with opposition players, match officials and the like. I would urge anyone who fancies watching a game of real football to find out when their nearest team is next playing and to get down there and enjoy it.

John Wadman

Quinton, Birmingham

A hex on Wrexham?

Sir: In his otherwise astute defence of non-League football, Neil Clark states that since being taken over by Hollywood stars Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney, Wrexham FC ‘have not looked back’. Here in north Wales, this is not the view of all Wrexham supporters. The actors’ determination to make the club a global brand may have widened its fan base and helped secure promotion last season. However, in the process, the club has forfeited much of the homespun identity that Clark alludes to when explaining the appeal of lower League football. With so many new fans and with blocks of seats routinely put aside for the club’s international supporters, many lifelong fans from the Wrexham area now find it impossible to obtain match tickets. And while pre-season games once involved trips to places not too far away – Stoke, for example – today’s team jets off to the USA to play a Manchester United youth team.

Nor does celebrity backing guarantee success: back in the EFL, Wrexham have won just one of their first four matches while conceding 13 goals.

Richard Kelly

Nant Mawr, Flintshire

Bell’s restoration

Sir: It was with the assistance of repeated interventions from Charles Moore that the reputation of the great Bishop Bell was rescued from the terrible damage inflicted on it by Archbishop Welby and the current Bishop of Chichester, Martin Warner. As he says, the return of George Bell House ‘all but completes the formal restoration of Bell’s reputation’ (Notes, 5 August). In Chichester, its final and absolute completion should take the form of a service of rejoicing and thanksgiving in the cathedral on 3 October, the date of Bell’s death on which he is commemorated in the Anglican calendar.

One final task would then remain. When Bell was unjustly condemned in 2015, work stopped on the statue of him that is to be erected on the west front of Canterbury cathedral, where he served as dean from 1924 to 1929. The cathedral announced in 2019 that the statue would be completed. Archbishop Welby said he was ‘delighted’. Yet the resumption of this work in his own cathedral is still awaited.

Alistair Lexden

House of Lords, London SW1A

Anti sociology

Sir: Rod Liddle’s excoriation of the dominant strands of sociology (‘The great sociology con’, 19 August) was spot on. But he missed the dissidents. There is a minority of sociologists who teach that knowledge is achieved by reliable evidence, not ideology or identity. They tend to believe that biological sex is real, that meritocracy has widened opportunity, that the legacy of the British Empire is complex rather than straightforwardly evil, and that the welfare states have, on the whole, transformed capitalist markets to serve human needs. They also tend to the view that the best evidence comes from good-quality social statistics, analysed in mathematically rigorous ways. These views are heretical in sociology. But they provide society with the potential to understand itself wisely.

Lindsay Paterson

Emeritus Professor of Education Policy, School of Social and Political Science, Edinburgh University

Accounted for

Sir: Martin Vander Weyer (Any other business, 19 August) says ‘no one ever erects monuments to accountants’. I recall on a visit to the Normandy beaches, specifically Omaha Beach, seeing a small war memorial to US Army accountants. I have tried, without success, to find a reference online. I wonder if any of your readers have any recollection of it?

Mike Barrett

Wiltshire

Why everyone thinks they could be President

Who is Perry Johnson? It is a question not many American voters can answer. He has a grand total of 16,000 followers on Twitter and recently pulled in precisely zero votes in a poll in Des Moines, Iowa. He describes himself as a ‘self-made businessman, problem-solver and quality expert from Michigan’. Nevertheless, this slightly cadaverous-looking businessman has joined the running to be the Republican party’s candidate for president.

There have been so many upsets in American politics of late that almost everybody thinks they have a chance

Does he stand a chance? Nope. The main way through he has found so far is by buying up advertisements on the right-wing channel Newsmax. There are claims that the channel has offered him favourable coverage – or indeed any coverage at all – in return for this largesse. Claims that Newsmax denies.

But is his case completely hopeless? Well, for any hopeless optimist the answer these days can always be ‘not necessarily’. Because there have been so many upsets in American politics of late that it’s understandable that almost everybody thinks they have a chance.

Take Vivek Ramaswamy, a 38-year-old entrepreneur and author of several anti-woke books. When he announced his candidacy for the presidency in February many people assumed it was just an exercise in profile-raising. I admit I thought along those same lines. I know Ramaswamy and like him. But it felt slightly like Lionel Shriver or Rod Liddle putting themselves forward for the job of UK prime minister. Yet Ramaswamy swiftly pulled ahead of some of the more obvious candidates, and this sort of breakout in turn gives everyone hope. Including false hope.

All polls still show Donald Trump way ahead in the field. His closest challenger is Ron DeSantis of Florida. But in some polls Ramaswamy is even pulling ahead of DeSantis, a testament partly to the uncertainty at the heart of the DeSantis campaign.

Ramaswamy has plenty going for him, but then almost everybody who puts themselves forward for the presidency believes they do too. One of the joys of recent months has been watching people with almost zero name recognition portentously announcing, before some hastily arranged flag, that they too are willing to serve. Among them are such non-household names as Doug Burgum and Will Hurd, two candidates whose announcements I suspect are designed to trip people like me up on television and make us predict, to a bewildered nation, that we should not forget about Douglas Hurd.

These people all linger below the 1-2 per cent group. But what is strange is that the 1-2 per cent group itself contains many of the people thought of as plausible candidates. It includes Senator Tim Scott, the former American ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, and the former vice-president Mike Pence. Obviously it is a group that Perry Johnson and others dream of getting into. But even they look as though they are fighting a battle they know they must lose.

Chris Christie is fighting an impressive campaign, the main aim of which appears to be to take out Trump. By now there isn’t a person on the planet who doesn’t know Trump’s weaknesses. But Christie (who prepped Trump for past debates) knows how to press Trump in a way not many people do. Still, it seems a kamikaze mission, for even if Christie were successful in taking out Trump, it is not clear how any of the resulting benefits would haul him above his current 2 per cent position. Yet it is in that dream of a post-Trump world that some hope lies for all. Pence, because of his one-time proximity to Trump, seems similarly well placed to wound him. But it is equally unlikely that he would be the beneficiary of the votes which would come free if Trump didn’t make it to the finish line.

The oddity of US politics is that it is remarkably locked-in. Even more than in the UK, the party structures have a stranglehold which seems unbreakable. Except that every now and then someone does break it. Barack Obama did it in 2007, when the then relatively unknown junior senator announced his vision for America, rolled over the Clintons and went all the way to the White House. In 2016 Donald Trump performed a similar disruption when he insulted his way past the other Republican candidates and (once again) rolled over the Clintons. How everyone laughed at Trump’s candidacy, until they didn’t.

The thought that such one-offs are in fact semi-regular is what gives those languishing at the bottom of the polls some hope.

But still it takes an unusual person to pull it off – and unusual in at least some good ways. At a campaign meeting in Iowa last week Perry Johnson gave a performance so unhinged that it made Howard Dean’s famous 2004 scream seem positively hinged. As he tried to rally the crowd, Johnson screamed about Iowa and at the top of his lungs started belting out: ‘Let’s do it. Let us do it. Now! Now! Noooooow!’ At which point he almost fell off the stage and then remarked as much to the crowd.

Having failed to make this week’s debate stage, there will be an attempt to persuade people like Johnson to stop unnecessarily crowding an already overcrowded field. Yet here is the unspeakable thing. Even if you add all those zeros together, throw in all the 1-2 per cent contenders and ask everyone to stand behind a unity candidate, nobody even approaches Trump in the polls. Indeed Ramaswamy, DeSantis and everyone else could pool their support and still not get near Trump. And that is where the real challenge lies. The success of Trump’s 2016 strategy has given inspiration to a lot of other contenders. But it also highlights what a singular phenomenon the Trump phenomenon was – and continues to be.

Why can’t NHS managers spot a serial killer?

No one who has paid any attention to NHS scandals over the past few decades should be at all surprised by the way in which managers at Lucy Letby’s hospital repeatedly dismissed concerns about her. When worried consultants produced considerable evidence to show that the nurse was present at every single event where a baby had dramatically collapsed or suddenly died, they ended up being the ones in the firing line. Management even forced them to apologise to Letby personally at an HR meeting, to which, bizarrely, the nurse brought along her parents.

Doctors are suspicious of the calibre of those managing them, and the managers are often on the defensive

Yet in the NHS, monumental managerial failures are not unusual, they’re typical. In the independent inquiries into all NHS disasters of recent years, such as Mid Staffordshire, Morecambe Bay and Shrewsbury and Telford, there is one common theme: the managers got in the way of those trying to get to the truth. From scandal to scandal, nothing seems to change.

NHS managers are often the bogeymen in healthcare. Clinicians love to denigrate their clipboard-clutching overlords. The only time I’ve ever heard someone booed at a church service was when I was in a congregation that was stuffed to the rafters with doctors from the local NHS hospital and a young woman stood up to say she was an NHS management trainee. And if you want to get a few cheap cheers as a politician, you can call for the managers to be abolished – as Liz Truss did when she was campaigning for the Tory leadership last year. In fact, it was Truss’s heroine, Margaret Thatcher, who brought in general management to the NHS after discovering that no one was effectively in charge of hospitals.

On paper, when compared with many more effective health systems, the NHS is actually quite under-managed. If you include administrators as well as executives, managers make up around 27 per cent of all staff in the health service. But those figures tell us nothing about whether the management culture is any good.

It isn’t. It is hard to find anyone working in the health service who doesn’t think it has a problem with bullying. The origins of the management bullying culture lie in those Thatcher reforms of the 1980s. Shocked by a rise in the number of people working in the NHS, the then prime minister commissioned Roy Griffiths of Sainsbury’s to review how the service was actually being run. He came back to her with the conclusion: ‘If Florence Nightingale were carrying her lamp through the corridors of the NHS today, she would almost certainly be searching for the people in charge.’

What followed was the introduction of general managers, something contested at the time by healthcare unions, who felt their members should be the only ones eligible to run a hospital. Very few clinicians ended up in general management, in part because of the hostility of their organisations to the reforms, but also because the NHS became obsessed with hiring people from outside, on the basis that they would have a better perspective on what was going wrong. That led to a ‘them and us’ attitude that persists today. Doctors are suspicious of the calibre of the people managing them, and the managers are often on the defensive. It’s not hard to see how that dynamic made the conversations between doctors and managers at the Countess of Chester hospital much harder.

Standoffs between the two groups are a regular feature of NHS life. One manager at Guy’s hospital recalled to me that ‘to save money, managers literally locked – chained and padlocked – some operating theatres to stop some of the cardiac surgeons operating’. Some managers didn’t know how to manage: one administrator from the early years of general management in the 1980s says that many of his colleagues behaved as though they were on a City trading floor, while another remarks that they couldn’t cope with the level of accountability they were supposed to take on: ‘Because people were now responsible for failings, they were frightened of those failings being spotted at all. It wasn’t healthy, isn’t healthy.’

The New Labour years were in many ways bountiful for the NHS. There was higher spending and a lot of political attention directed at neglected hospitals and wards. But the bullying culture only worsened. Some of it was exported from the world of politics, which was going through a macho period of control freakery. The desire to see results for the extra money meant there was a relentless focus on meeting targets, to the extent that an invitation to sit on the health secretary’s sofa became as infamous as a boat trip to Traitors’ Gate. Alan Milburn was then in charge of the sofa of doom. One executive remembers: ‘You didn’t want to be invited to sit on the sofa in his office. Because it was heading for him shouting at you and using really foul language.’

What all these managers, from the very top of the organisation down to individual hospital wards, were frightened of was the statistics making them look bad. It wasn’t a fear of not learning from mistakes so that catastrophes only happened once. It wasn’t whether patients and their families were suffering or unhappy with their care. It was about the person above them coming down to shout. No wonder executives at the Countess of Chester resented the push from doctors in Letby’s unit to examine why babies kept dying without warning: there was no incentive to uncover a scandal at the hospital.

The political row at the moment is whether the Letby inquiry will be a public one or a quicker non-statutory one. There are lots of arguments in favour of giving the inquiry the sort of powers that come with a statutory footing, including witnesses giving evidence under oath. The bigger problem will come once that investigation has reported. It may well be full of ideas, maybe even regulation of managers. But if previous inquiries are anything to go by, nothing will really be done – and we will have to wait for the next scandal.

Therapy has turned on itself

Were I to overcome a lifelong scepticism about the healing powers of talk therapy, I imagine languishing on a psychiatrist’s divan and whimpering something along these lines: ‘All this “woke” stuff – I’ve even come to hate the word. Resisting its idiocies is taking over my life. I worry that I’m not setting my own agenda. When you decry something as stupid, aren’t you still babbling about something stupid? It’s a big, wonderful world out there, and “wokery” is killjoy, reductive and mean. I feel trapped.’

Yet according to the recent essay collection Cynical Therapies, I’d elicit an icy response. ‘Look here, Karen,’ my hypothetical therapist charges with a scowl. ‘Your only claim to my sympathy is being female. Otherwise, you’re criminally white, straight, cis and non-differently abled. Those sad little tits and crumbling knees can’t earn you out of the white supremacist oppressor class. Unless you suddenly decide that all along you’ve been a boy, you must devote yourself to anti-racism, apologise for having ever been born and do the work!’ Thanks, pal. Just what I needed.

Patients can expect to be lectured about their ‘privilege’ and ordered to proselytise for their own extermination

The contributors to Cynical Therapies are lecturers and clinicians in mental health who are raising the alarm about the ideological takeover of their discipline over the past 20 years. A mix of Americans and Brits – with the usual lack of dignity, the field in Britain has slavishly followed America’s into the abyss – the authors are heretics and, to many colleagues, traitors. The book is a cry for help.

Few doctrines could be more self-evidently antithetical to the traditional imperatives of psychotherapy than ‘critical social justice’, aka that tiresome, overworked term beginning with ‘w’. Although psychiatry has developed a wide range of approaches, not long ago therapists of all persuasions were coached to display openness, empathy, curiosity and neutrality. Good therapists avoided prescriptive ‘answers’, which the patient was encouraged to arrive at independently. They withheld judgment, appreciated complexity and, most of all, listened. Focus was on the individual. The premise of the therapeutic process was that people can be helped to change. Why else would patients show up?

CSJ, along with its little brother, critical race theory, is a closed system – like those articles to which you can no longer add comments. It espouses perfect certainty: every human relationship is about power. You’re either the oppressed or the oppressor, and this world view recognises no other categories. Far from being empathetic, the creed is pitiless, especially regarding popular majorities. Neutrality? Please. Fun extracurricular activities: labelling, blaming, shaming and getting people sacked.

Postmodern progressivism has all the answers and will happily shove them down your throat. It’s about nothing but judgment. It has no time for complexity. Given its simplistic formulas – you’re a good person or a bad person – whatever is there to be curious about? Its crusading converts aren’t listeners but preachers. The catechism has no interest in the individual. ‘Identity’ is wholly conferred by membership of groups, into which we’re helplessly born. This theology endorses predestination: western countries are irretrievably racist, and white people are damned. Hardly a perspective that allows for every patient to get better.

Accordingly, if folks who can’t credibly claim to be victimised by giant social badness make appointments with graduates of modern psychology programmes, patients can expect to be lectured about their ‘privilege’ and ordered to go forth in sackcloth to proselytise for their own extermination. Any problems such moral filth brings to the office will be interpreted as guilt pains over bigotry (something like trapped gas). Were you hoping to tease out your ambivalent relationship to your mother, tough luck. If you’re conservative or simply male – that is, a proponent of ‘masculinity ideology’ – go home.

Certifiably ‘minoritised’ patients aren’t much better off. Their troubles are now understood only in the context of oppressive structural forces they’re too weak to resist. Rather than nurture resilience and responsibility, writes one Jungian lecturer, ‘We encourage a mentality of victimhood which keeps them trapped in outrage and powerlessness.’ As for the trans contagion, psychotherapy has predictably swallowed ‘affirmative care’ hook, line and sinker, making clinicians complicit in what’s bound to be viewed, once we come to our senses, as this century’s most unforgiveable medical scandal.

Why would anyone seek counselling to be browbeaten with a partisan cudgel? They wouldn’t. Thus, writes Cynical Therapies editor Val Thomas, ‘The most likely outcome will be the chaotic breakdown of the field itself. As CSJ moves through the therapy professions in its usual manner, dismantling, disrupting, decolonising, and problematising all that exists therein, it will hollow out the centre.’ When clinicians aim no longer to heal but to morally re-educate their patients, therapists aren’t therapists, and ‘the whole house of cards’ will collapse.

What’s happened to psychotherapy is, writ small, what’s happened to western education, healthcare, left-of-centre governments and NGOs, as well as the civil service, the sciences and the arts. By its nature, this nihilistic doctrine corrupts from within every sphere it invades. CSJ resembles the fibrous, species-threatening fungus in The Last of Us, which smothers cities and takes malign control of human minds. At length, elites oppose the very purpose of their professions. Hence the National Trust despises the culture it’s pledged to preserve. The British Museum gives away its artefacts. Doctors reject western medicine for indigenous superstitions. Classicists denounce the Greeks and Romans as too white. English professors renounce Shakespeare. Therapists renounce therapy.

I’m tepid on therapy myself. For a few well-off friends in New York, weekly sessions of introspection seem an overpriced indulgence. Still, parents of anorexic, suicidal or addicted kids must be desperate for a resort, and sometimes advising ‘maybe you should see someone’ provides the merciful illusion of ‘doing something’. At least talking out problems won’t likely do any harm, and making any positive commitment can be a first step to solving them. What is not a solution is being indoctrinated into a belief system that is ugly, cruel, hopeless, arid, crude, rigid, deterministic, civilisationally annihilative and, yes, you guessed it, stupid.

House prices are falling. But it’s still terrible for first-time buyers

Hurrah. Housing is now more ‘affordable’ for first-time buyers than it was a year ago. Or so says Halifax, which has produced figures this morning showing that the average home now costs 6.7 times the earnings of the average worker, down from 7.3 times a year ago. This is thanks to two opposing trends. The value of the average home has come down from £293,586 to £286,276. Meanwhile, average earnings have increased by around 7 per cent.

Spot the missing factor from this analysis. Yes, that’s right: it’s interest rates

Spot the missing factor from this analysis. Yes, that’s right: it’s interest rates. Housing is only more ‘affordable’ now than it was a year ago if you are lucky enough to be able to buy without a mortgage or you have someone happy to lend you money privately, interest-free. For everyone else, buying a home is definitely not more affordable than it was last year. Little over a year ago you could fix your mortgage for around 2 per cent. You would be extremely lucky now to fix it at less than 6 per cent.

If the average home now costs 6.7 times the average salary, that is way, way above what it was last time interest rates were at the level they are now. When I bought my first home in 1993, there was a very simple rule: to find out what you could borrow you multiplied your annual earnings by three. Add on a small deposit and it was hard for first-time buyers to afford a property that was valued at much more than three and a half times average earnings. That, as a result, was about the level at which house prices settled – before years of falling long-term interest rates tempted lenders to relax their lending practices, buyers were lured with offers of much larger mortgages – and house prices soared as a result.

If we are going to go back to the days of 6 to 7 per cent mortgage rates, then house prices are going to have to fall a lot further before they are going to be affordable for first-time buyers. If house prices are going to return to being 3 to 3.5 times the average salary they will have to halve. That doesn’t necessarily mean they will halve. More than half of owner-occupied homes are now owned without a mortgage, so there are relatively few forced sellers there. Some property investors have been forced to sell as a result of rising mortgage rates, but a lot will hang on and enjoy rising rental income. The mentality of property investors and owner-occupiers also comes into it: there are a great number who, once they have established in their heads an idea of what their property is worth, will refuse to sell it for anything less. The housing market, as a result, has a tendency to stagnate rather than crash.

But one thing is for sure: home ownership is not going to become affordable for first-time buyers unless the ratio of average home values to earnings falls to somewhere closer to its historic value of 1:3. That is going to require either a sharp drop in home values or a continued rise in earnings – or a combination of the two. There is unlikely to be a rapid resolution to the affordability problem.

At the Science Gallery I argued with a robot about love and Rilke

A little-known fact about the Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument, the first sampling synthesiser, introduced in 1979, is that it incorporated a psychotherapist called Liza. Stressed musicians could key in an emotional problem and Liza would begin the session with the soothing opening: ‘What is it that troubles you about x?’ She was flummoxed by a frivolous question from my husband, an early Fairlight owner, about a hole in her bucket but dealt expeditiously with my nine-year-old stepson. When he told her to get lost, she shut the system down.

The closing installation is a dismal graveyard of discarded Alexas still winking pink, blue and green

The ghost in Fast Familiar’s machine at the Science Gallery’s AI exhibition is an advanced version of Liza, and the roles are reversed. ‘You might be used to robots helping you,’ it advises visitors. ‘But this is about YOU helping ME.’ As a human (you have to pass a traffic-light test to qualify) your role is to help its artificial intelligence look for love by teaching it the basics of romance.

Not a ready learner, it is easily rattled. When I hit the ‘No that’s not true’ button in response to its boast, ‘we can use data to predict love efficiently’, it snapped back: ‘You may not be able to but I can.’ When I zero-rated its attempt to up the romance quotient in Maria Rilke’s love poem Again and Again by inserting ‘bouquets of red roses’ into the penultimate line it responded tetchily: ‘That was not what I was expecting.’ The Mike Nelson-style setting of an internet café with misspelt notices from the management and a broken electric fan is a giveaway that the intelligence at work here is artistic. The responses are too funny for a chatbot – and too clever by half.

As you might expect from a collaboration between scientists and artists, the show is a mix of the serious and the surreal. On the more serious side, there are works about the use of AI in health settings, from designing cochlear implants to treating sufferers from heart disease and cancer, and helping people navigate the immigration system. There’s a study space where you can loaf on giant cushions listening to Mozilla’s podcast series Online Life is Real Life – I heard South African journalist Justin Arenstein, co-founder of data journalism initiative Code for Africa, explaining the problem of countering online disinformation on the continent where 500 languages are spoken in Nigeria alone. (‘Trying to fact-check everything is whack-a-mole.’) On the surreal side, James Bridle’s looping video ‘Autonomous Trap 001’, set in a car park near Greece’s Mount Parnassus, shows a self-driving car built by the artist repeatedly immobilised within a salt circle of prohibitory road markings, spellbound not by witchcraft but its own software.

Whether AI text-to-image generative tools are capable of grasping the essence of a human subject is the question addressed in Munkhtulga Battogtokh and Alice White’s art installation ‘What is Essence?’. Judging by Midjourney AI’s idea of what a professional portrait of a medical man should look like, the answer is no. In his white coat and dark glasses, their grim-faced ‘Doctor’ belongs in a horror movie. Midjourney needs to machine-learn a bedside manner.

Midjourney needs to machine-learn a bedside manner

There’s a dystopic feel, too, to the futurist utopia imagined in artist collective Blast Theory’s film ‘Cat Royale’. The guinea pigs in this experiment in robotic pet-sitting are three cats, Ghostbuster, Pumpkin and Clover, filmed over several days being fed and entertained in a brightly coloured play environment by an AI robot arm. The arm puts down food, dangles strings, rolls balls and drags a blanket around. The string acts on the cats like catnip – they look seriously overstimulated – but the Small Dimpled Ball Ramp Roll game leaves Clover cold, lowering her happiness score by 1 per cent. My sympathies were with Pumpkin, whose happiness scores remained stubbornly low. Amusing as it is to watch, it’s not funny to think that similar systems of measurement are used on us. The chance to engage with a real robot is offered by Sprout, created by robotics studio Air Giants in the shape of a huge white, soft, interactive tongue which visitors are encouraged to touch and hug. When I touched it, it blushed a livid violet and leant into my space as if inviting me to tango; when a male visitor tickled it, it waggled with apparent excitement. But Sprout’s touchy-feeliness didn’t reassure me that humanity can ‘take collective ownership of the systems that feel beyond control’, as the show’s organisers hope, or that the spread of robotics is good for the planet. Wesley Goatley’s closing installation ‘Newly Forgotten Technologies’ is a dismal graveyard of discarded Alexas still winking pink, blue and green in the dark, their rare-earth minerals, millions of years in the making, returned to the Earth as smart trash in the blink of an eye. No such fate awaits the Fairlight, a collector’s item – but I wonder what became of Liza.

Two very long hours: The Effect, at the Lyttelton Theatre, reviewed

Lucy Prebble belongs to the posse of scribblers responsible for the HBO hit, Succession. Perhaps in honour of this distinction, her 2012 play, The Effect, has been revived at the National by master-director Jamie Lloyd. The show is a sitcom set in Britain’s most dysfunctional drug-testing facility where two sexy young volunteers, Tristan and Connie, are fed an experimental love potion that may help medics to find a cure for narcissists suffering from depression. Running the experiment are two weird boffins, Professor Brainstorm and Nurse Snooty, who once enjoyed a fling at a conference and whose lust is not entirely extinct. But Nurse Snooty is playing hard to get. ‘Sometimes,’ she tells the Professor, ‘I feel I’m dead but my body hasn’t caught up yet.’ The Professor, a psychiatrist by trade, fails to spot the negative signals here and continues to bombard her with lecherous suggestions.

Every low-budget filmmaker knows that black and white makes boring look classy

Meanwhile, in the mixed-sex ward, Tristan and Connie are flirting like mad even though they have nothing in common. She’s a feminist psychology student who likes older professional academics. He’s a penniless half-wit from east London who makes a living by volunteering for medical trials. Yet Connie seems mysteriously smitten with this talentless creep even though he mocks her accent and mannerisms. And she encourages his mistreatment by tittering uncontrollably at his jibes.

To explain her nervous giggles she spouts antique psychological platitudes. ‘Female laughter is a show of submission,’ she says. Since the two lovebirds have swallowed a medical aphrodisiac, their flirtation owes more to pharmacology than to desire and this makes the romance feel contrived and half-cooked.