-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

You’ll be pleasantly surprised at how unpleasant this is: Strays reviewed

Based on the poster showing two cute dogs – a border terrier and a Boston terrier – I had assumed Strays was a (probably lame) kiddie film with a remit to amuse the aforementioned kiddies during the long, long, very long summer holidays, so here’s what I was saying to myself during the opening moments: ‘Christ on a bike, what the hell is this?’ I can now tell you that Strays is vulgar, rude, offensive and disgusting. But the biggest, weirdest shock? At a certain point I realised it was funny, and rather touching, and that I was having fun. In other words, I was pleasantly surprised. Or, given its frequent scatological content, pleasantly surprised, unpleasantly.

Here’s what I was saying to myself during the opening moments: ‘Christ on a bike, what the hell is this?’

The film is directed by Josh Greenbaum and written by Dan Perrault, and our main dog is the border terrier, Reggie (voiced by Will Ferrell, who of course had to be somewhere in the mix). We first meet Reggie running through a field and chasing butterflies while declaring: ‘This is a great day, the greatest day!’ But it turns out that his owner, Doug (Will Forte), is a stoner brute. Reggie doesn’t know that his name is Reggie. He thinks his name is ‘Dumbass Shitbag’ – you see now how this differs from Lady and the Tramp – because that is what Doug always calls him. Doug kicks Reggie and throws cans at him and shuts the door against him. I did not enjoy this part. I don’t want to see dogs treated cruelly. I am still traumatised by Old Yeller 50 years after the fact. But Doug wants rid of Reggie, as we will always call him, so drives him further and further away, throws his ball, drives home without him. Reggie thinks this a game, the best game, and it’s his job to bring the ball back, as he always does.

But then Doug drops him in the midst of a city many miles away where Reggie is at a loss until he meets another bunch of strays: Bug, the Boston terrier (voiced by Jamie Foxx), Maggie, the rough-coated collie (Isla Fisher) and a great dane, Hunter (Randall Park). Hunter is not insignificantly endowed, shall we say, and when complimented happily confides: ‘I like to keep it clean. I lick it a lot.’ These dogs are potty-mouthed and the F-word abounds as they teach Reggie to negotiate the streets and introduce him to their favourite pastimes, like humping garden furniture. Reggie, who is still pure of spirit, insists he isn’t a stray, but when he tells them what he thinks his name is, the others get it. Eventually Reggie gets it too and they plot their revenge: they will find Doug and bite his penis off. There is no gentler way of saying it.

They have their adventures on their way. Some are full-on gross – an escape from the clutches of Animal Control is scatologically full-on – but some are uncommonly smart, such as the scene involving a labrador (‘the Narrator Dog’), and there is also a clever cameo from Dennis Quaid. The dogs are impeccably rendered. Unlike, say, Cocaine Bear, this isn’t pure CGI. Instead, it’s a complicated mix of real dogs and special effects and the results are stunning. All the strays have a backstory and the film understands the nature of dogs much better than, for example, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs. It is funny, I think, because it finds some kind of balance between its wild excesses and saying something true about man’s best friend. Will Reggie bite Doug’s penis off? Or, when it comes to it, does he just want Doug to call him ‘a good boy’? I welled up at the end. You may like it. Just don’t take the kids.

Trump, Diogenes, the Mitfords and Malaysian comedy: Edinburgh Fringe round-up

The Mitfords is a superb one-woman show by Emma Wilkinson Wright who focuses her attention on Unity, Diana and Jessica. In the early 1930s, Unity became Hitler’s lover and she lived in a luxurious Munich apartment confiscated from a wealthy Jewish family. The Führer, whom she nicknamed ‘Wolfie’, gave her the pearl-handled revolver with which she shot herself in the head shortly after Britain’s declaration of war. To carry out this bizarre act of self-sacrifice she chose a favourite spot in Munich’s English Garden where she used to sunbathe naked. In wartime Britain, Diana was held in Holloway prison and she complained bitterly about being separated from her baby boy, Max, and about the hefty sandbags that prevented daylight from reaching her cell. The lack of sun seems to have caused her more distress than the lack of son. Her sister, Jessica, tried to embrace Bohemian bliss in Rotherhithe but she struggled to cope without servants. ‘After hours sweeping the stairs I realised you have to start at the top and work down.’ This show is a must for Mitford connoisseurs who want to relive their favourite moments from the clan’s erratic history.

Sarah Lawrie’s poised, nerveless performance is riveting

The Good Dad (A Love Story) is a harrowing yarn about rape and incest. The ironic title refers to a monstrous predator who impregnates his young daughter, Donna, on four separate occasions. Her family cover up these crimes but as Donna grows into womanhood she decides to take bloody revenge on the man who occupies three roles in her life: father, partner and rapist. Sarah Lawrie’s poised, nerveless performance is riveting.

The Briefing opens as a partisan rant by a pro-Dem comedian, Melissa McGlensey, who poses as a Trump fan in order to mock him. ‘Who can tell me what the “J” stands for in Donald J. Trump? Genius.’ She then adopts the persona of the Republican governor of Arkansas, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, and the show turns into an improvised press conference. Brilliant fun. McGlensey is exceptionally quick on her feet and she never hesitates when fielding questions. ‘What books would you ban from elementary schools?’ shouts somebody. ‘All the ones with words in them.’

All About Philosophy in 100 Jokes is a series of comic asides about famous thinkers by Oleg Denisov. Two examples. ‘Diogenes was a penniless hermit who lived in a barrel – which is what happens when you fail to provide basic mental healthcare facilities.’ And he jokes that Nietzsche’s decree, ‘if thou goest to woman, take thy whip’, came from the German philosopher’s keynote speech to the Zurich BDSM festival in 1876. He makes the same joke about Rousseau’s comment that ‘man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains’. The only problem is Denisov suffers from surges of uncontrollable rage. His show ends with a crazed diatribe about classic Russian literature, and a random opinion screamed at pane-shattering volume.

Inside No. 10 gives the excellent Matt Forde a chance to imitate Keir Starmer’s whiny, high-pitched delivery. And he adds a note of self-righteous pettiness that’s even more accurate than Starmer’s needling voice. To mock Nigel Farage’s financial woes, Forde imagines a pro-EU Coutts manager making a call to explain why the bank has withdrawn Farage’s account. ‘We’ve decided to stop the free movement of our financial services, Mr Farage, and to take back control of our investment portfolio. And, by the way, Leave means Leave.’ Forde tells us that all professional politicians are trained to avoid using the words of an accusation when issuing a denial. But this trick has yet to be mastered by Humza Yousaf. ‘I watched him on TV,’ says Forde, ‘and he actually said this: “The SNP is not a criminal organisation.”’

Rizal Van Geyzel ran the first comedy club in Malaysia for ten successful years until a female comic brought the whole thing crashing to the ground. Performing in a niqab, she recited verses from the Quran while doing a striptease which gradually revealed a suggestive outfit beneath her modest Islamic garb. A pretty forgettable routine but the entire act was filmed and posted online. Cultural meltdown ensued. She was arrested and jailed while Van Geyzel, also briefly imprisoned, was compelled to close his club for good.

Since then, he’s prospered on the global circuit and he races through his 60-minute set peppering the material with snatches of Chinese, Tamil and Malay. He seems to have picked up four or five languages without the slightest effort and his English is good enough to feature decent attempts at Cockney and Glasgow accents. Being Muslim, he discusses the Quran and the quirks of Islamic fundamentalism with an insouciant freedom that seems alien to the culture of English stand-up. If he hit the London circuit, he’d be busy every night of the week.

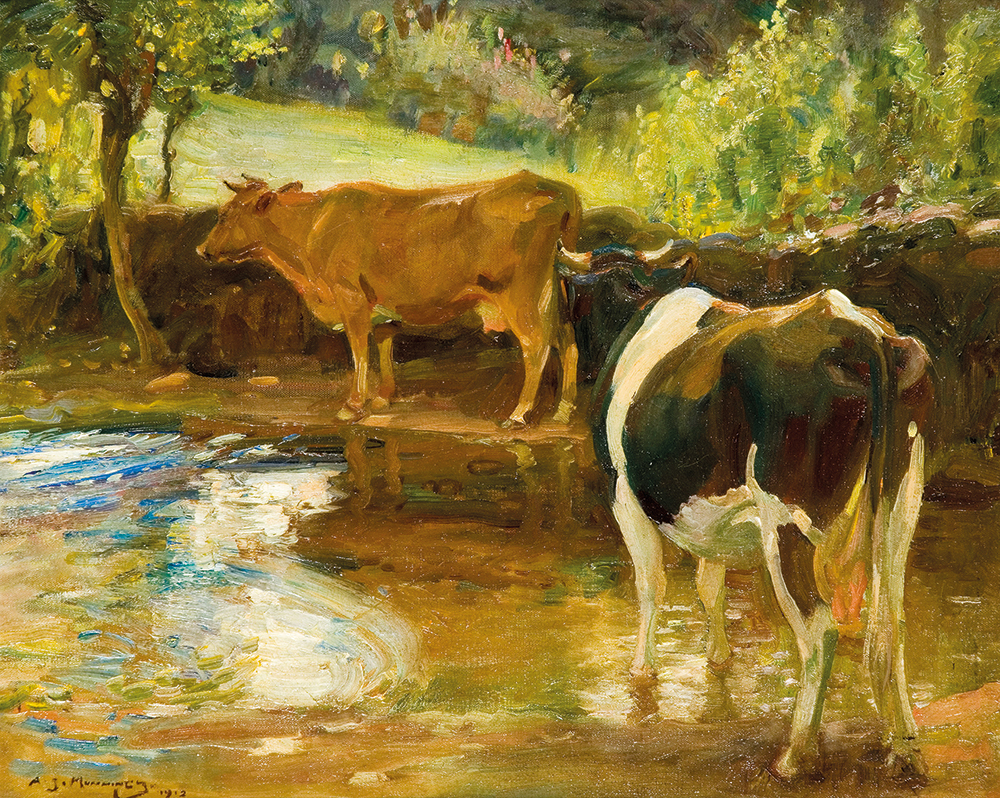

An extraordinary woman: The Art of Lucy Kemp-Welch, at Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, reviewed

In March 1913 two horse painters met at the Lyceum Club to discuss the establishment of a Society of Animal Painters to raise the profile of their genre. Of the two, it was Alfred Munnings whose profile needed raising. Lucy Kemp-Welch had been a celebrity since her twenties when her 5x10ft canvas ‘Colt Hunting in the New Forest’ caused a sensation at the 1897 RA Summer Exhibition and was purchased by the Chantrey Bequest for the new National Gallery of British Art on Millbank.

She threw herself into every activity she depicted, whether rounding up colts or hauling timber

The daughter of a Bournemouth solicitor, Kemp-Welch had been riding and sketching horses since the age of five and had developed a photographic memory for catching them in action. Her first Academy submission, ‘Gypsy Horse Drovers’ (1894), painted while still a student at Hubert von Herkomer’s Art School in Bushey, was inspired by the sight of gypsies driving horses through the village to Barnet Fair; rushing out after them, she had dashed off an oil sketch on the wooden slide of her paintbox. As fresh as the day it was painted, the sketch hangs in the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery’s current retrospective curated by David Boyd Haycock, author of a new biography of this extraordinary woman who threw herself into every activity she depicted, whether rounding up colts or hauling timber.

To Kemp-Welch, every horse was an individual: ‘Mixed Company at a Race Meeting’ (1905) is a tour de force of equine group portraiture, the foreground horses’ heads so close to the picture plane you could pat them and feed them sugar lumps. A race meeting was an unusual subject for a painter who preferred working horses, finding racehorses ‘too perfect, polished and shiny… Perfection in the subject painted does not lead to interest in the picture,’ she thought. She made an exception for the Royal Hanoverians in ‘Aristocrats’ (1928), stars of Sanger’s Circus which she followed on the road every summer until too old to crank her old banger ‘Spitfire’.

Despite showing in every RA Summer Exhibition between 1895 and 1930 bar one, Kemp-Welch was never elected an academician. She was considered for associate membership after ‘Colt Hunting’, but worries about who would escort this quiet little woman into the annual Academy banquet scotched her chances. The RA was a boys’ club. Munnings, a party animal, was a better fit; within six years of their Lyceum meeting, he was an associate member.

Like Kemp-Welch, Munnings was a precocious draughtsman, practising as a child on the horses that came and went from his father’s Suffolk mill. At the age of 20, the jockeys and gypsies at Bungay Races awakened the love of colour that is the focus of the Munnings Art Museum’s current show. The loss of sight in one eye while helping a puppy out of a thorny hedge only increased his awareness of colour: he became a connoisseur of florid complexions set off by the scarlet flash of a hunt coat.

‘Pink is an artist’s colour,’ said Munnings, and curator Marcia Whiting has assembled a Barbie wall of pinkish paintings to prove it. But he was no Ken. Moody and boozy, he achieved the rare distinction of being suspended from the Chelsea Arts Club for foul language. His first wife Florence tried to kill herself on their honeymoon and succeeded two years later; his second, Violet, took him in hand and appointed herself his business manager. He complained bitterly when she dragged him away from painting gypsies in Hampshire to fulfil a commission to paint the thoroughbred stallion ‘Rich Gift’ (1921), but he did him proud, catching the iridescence in his glossy brown coat. Unlike Kemp-Welch, he relished ‘the sheen of a clipped horse’, although he champed at exchanging country subjects for equestrian portraits. ‘It meant painting for money,’ Violet freely admitted. ‘He was never such a good artist after he married me.’

Munnings became a connoisseur of florid complexions set off by the scarlet flash of a hunt coat

The first world war made Munnings. Kemp-Welch had desperately wanted to go to France but resigned herself to painting gun teams training on Salisbury Plain; Munnings’s service as an official war artist with the Canadian Cavalry Brigade established his reputation. Elected ARA in 1919 and RA in 1928, he rose to become president in 1944. But with the demise of the working horse and the advent of modernism, both painters found their subjects and styles outdated. If Kemp-Welch is best remembered today for her illustrations to Black Beauty, Munnings went down in British art history for his notorious speech at the 1949 Academy banquet in which he slagged off the entire British art establishment for being in thrall to ‘foolish daubers’ like Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso. He resigned as president but went down fighting. The Barbie wall includes ‘Does the Subject Matter?’ (1953-56), the lampoon he showed at the 1956 RA Summer Exhibition three years before his death picturing Tate director John Rothenstein with a group of men in grey suits admiring a modernist sculpture in front of a wall of Picassos – in the company of a Selfridges model in pink.

Uneasy listening: Kathryn Joseph, at Summerhall, reviewed

I have always been fascinated by artists who bounce between tonal extremes when performing, particularly the ones who serve their songs sad and their stagecraft salty.

Adele, for example, fills the space between each plushily upholstered soul-baring ballad by transforming into a saucy end-of-pier variety act, coo-cooing at the crowd and cursing like a squaddie. John Lennon gurned and clowned his way through the Beatles’ concerts, subverting the naked suicidal plea of ‘Help!’ in the process. John Martyn would belch and joust in mock-Cockney at the conclusion of a particularly sensitive piece. Jackie Leven punctuated songs of immense pain and sadness with eye-watering stories of defecating in alleyways and getting blootered with the Dalai Lama’s bodyguard.

She salted her sorrow with between-song tales of intimate embarrassment

A bipolar approach to performance can puncture reverence, acting as a knee-jerk spasm against stifling solemnity. It can also be deployed as a defence mechanism to protect overly exposed nerve endings. It is certainly one way to keep an audience on its mettle and in a state of pliable unease. Yet it can be hard to gauge how much of this approach is a conscious strategy, and how much the unfiltered leaking out of an artist’s innate nature.

Which brings us to Kathryn Joseph. A singularly serious artist, Joseph won the 2015 Scottish Album of the Year award with her debut album Bones You Have Thrown Me and Blood I’ve Spilled. She has delivered on that early promise. Last year’s For You Who are Wronged was widely acclaimed – and justly so. Her music is sparse and spooky. Her words have the plainly poetic cadences of a spell or a curse.

Yet in Edinburgh, she salted her sorrow with between-song tales of such intimate embarrassment one would hesitate to share them with a best friend, never mind a paying audience. In the scatological subcategory of performer’s pillow talk, Joseph is clearly an Olympian. Most of her stories are frankly unrepeatable, and served to yank the mood of the show between a hushed haunting and head-shaking hilarity.

With our nervous laughter still echoing around the Dissection Room (Summerhall is a former veterinary school), Joseph would place her hands on the keys to play another hypnotic pattern on the electric piano and sing another hypnotic song for the abused, the broken, the disposed of and dispossessed. As an audience, we were caught off-guard by the shift and left oddly vulnerable. It was a neat trick, if a trick is what it is, serving ultimately to accentuate the seasick rhythms of her songs and their agitated hearts.

Introducing herself as a ‘drunken old lady’, Joseph was here to sing her ‘creepy little sad songs’ about bones and blood and betrayal. In a sense, her set – part of Summerhall’s excellent Festival ’23 programme – was one long mood piece. She sat alone at the piano, from which she coaxed thick, chewy, undulating grooves. From time to time, she flicked a switch and a primitive, thudding pulse marked time.

Joseph has a pleasingly weird way with syntax – exhibited on the closing ‘What Is Keeping You Alive Makes Me Wants to Kill Them For’ – and an equally idiosyncratic way with rhythm. These circular incantations at times wandered into the blunted edges of trip hop: ‘Tell My Lover’ elicited faint echoes of Portishead. The cascading piano motif on ‘Of All the Broken’ – preceded by a tale about smashing her head open while playing on a children’s waterslide in France – brought to mind the squelchy, slippery time signatures of prog rock. There were stirrings of folk, soul and jazz, and moments which recalled the becalmed, almost-silent passages of Talk Talk’s albums Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock.

Her voice curled at the edges as though singed, often sliding into an exaggerated miaowing vibrato, like an indie Eartha Kitt. Occasionally this elided into a wordless, primitive keen, suggesting a woodland creature in pain. ‘The Bird’, leavened with a music-box tinkle, felt as if it belonged to a lineage which includes both Billie Holiday and Beth Gibbons.

She played for a little over an hour, which was well judged. Joseph’s music isn’t exactly easy listening but there was much beauty to be found, and some solace, within her trauma-filled songs. ‘The Burning of Us All’ insisted that there was ‘no one coming’ to save the stricken protagonist, yet the closing verse held the promise of the cavalry arriving. ‘Mouths Full of Blood’ assured us ‘you will like this light’. For what is light without shade, and vice versa? Joseph asked the question, and she answered it too.

On the trail of Roman Turkey with Don McCullin

The genesis for our book Journeys across Roman Asia Minor was hatched in the autumn of 1973, when Sir Donald McCullin was a young man. He had been assigned by the Sunday Times to work with the writer Bruce Chatwin on a story that would take them from a murder in Marseille to the Aurès highlands of north-east Algeria. It was an emotionally gruelling journey and they rewarded themselves on the way back by stopping off to look at a solitary Roman ruin. No photographs were taken, but the memory of this place from all those years ago remained embedded in Don’s imagination. Three decades later, that seed bore fruit, as he undertook a series of visits to North Africa. I was lucky enough to accompany him on two of these trips, into western Libya and southern Algeria.

With lights sparkling in two pairs of eyes, we thanked our lucky stars for what we had seen

Don was locked into an affectionate dialogue with two of the pioneer photographers of this historical landscape: Maxime du Camp and Francis Frith. I heard from Don about the ‘startling clarity and precision’ that they had achieved with these first images of antiquity, their honest ‘factuality’, and how you could almost hear the crunch of their feet and taste the dust that had flicked up towards the camera lens some 150 years before.

Du Camp had travelled out to photograph the ancient monuments of Egypt between 1849 and 1851, in the company of another eminent Frenchman, Gustave Flaubert. Francis Frith was neither accompanied by some erudite companion nor endorsed by state funding. He was a self-willed, self-funded Anglo-Saxon who at the age of 33 dedicated himself to ‘the rage, the fury, the vexation of all kinds caused by my [obsession with] photography’.

Before this, Frith had set himself up as a wholesale grocer and could have gone on to become a Lipton or a Sainsbury. Instead he used the small fortune he acquired to finance his obsession. He photographed Egypt and the Holy Land during three separate expeditions, in 1856, 1857 and 1858. This project would eventually fill 13 volumes of photographs. Don and I managed just one – Southern Frontiers: A Journey across the Roman Empire, published in 2010. It is the sort of book you might wish to be buried with, but when the last copy had been sold we toyed with trying to make it even better by plotting an expanded second edition. Don was particularly keen to photograph Cyrene, but travelling into eastern Libya at the time had been made difficult by a civil war. However, as this door closed another opened.

Despite being one of the world’s most well-travelled men, Don had never explored Turkey, though he had chronicled many wars fought near its frontiers. I was able to assure him that the country would equal what he had seen of Roman North Africa. I was also able to tell him that, despite exploring the ruins of Turkey for the past 30 years with what my family considers to be excessive zeal, there were a large number of ruins I was still keen to track down.

There was one hurdle left: Don’s reputation as the world’s foremost war photographer. Such fame can open many doors, but it can have the reverse effect on frontier police and tourist visas, especially when he takes his camera bags. Moreover, I have travelled enough with Don to know that, although he is one of nature’s true gentlemen, his manners go into reverse with any man in uniform, who to him is like a red rag to a bull. So we decided there should be no sneaking about among the bushes with this project. We were workers, not tourists, and we would need formal permission to use tripods in museum galleries.

Before our first meeting at the Turkish embassy I was slightly nervous as to how it would go. But I should not have worried. The ambassador had been to Don’s retrospective at the Tate and had been moved that among all the many wars and massacres recorded, there had been space to testify to the sufferings of an ordinary Turkish family in Cyprus in 1963. The Turks get a lot of respect as a martial nation but they do not receive much empathy. The ambassador had not forgotten what he had seen. Over lunch I heard him assure Don that any photographer was free to travel to Turkey and click away at every Roman ruin to their heart’s content – but that Don would be particularly welcome.

We undertook three separate journeys across western Turkey, beginning in 2019 and ending last year, and made good use of the various Covid lockdown periods to travel the moment we were permitted to, but before the tourist crowds returned. We had some very simple ground rules. We would concentrate on the relics of the Roman Empire but also include what the Romans had repaired and used from previous ages. We would stay as close as possible to any ancient city in whatever accommodation we could find, in order to be up before the dawn light and to be able to linger on through into the dusk. We would make no plans that could not be changed should we happen upon anything beautiful on the road. All of this was made possible by two travelling companions: Ahmet Komurkıran at the wheel and Monica Fritz on her iPhone. Monica was our updated version of a traditional dragoman guide, busily plotting routes and unearthing interesting restaurants.

We focused on the Roman period, offering as it does a shared memory link with all Mediterranean and European cultures and, unless you have the immense good fortune to be born Italian, almost divorced from any sense of patriotism. It was also vital to draw a line somewhere, as Turkey is so full of monuments and the homeland of so many successive empires that we would otherwise submerge ourselves entirely in the richness of the landscape’s history.

When I last met Don, we rather tortured ourselves by unfolding an ancient map and tracing how little of Roman Turkey we had covered. Bithynia we just scratched the surface of; the provinces of Cappadocia, Cilicia, Pontus and Galatia were left completely untouched, let alone the Roman military frontier posts along the Euphrates valley. I then folded the map so that it framed western Anatolia alone, and with lights sparkling in two pairs of eyes, we thanked our lucky stars for what we had seen.

The ‘Asia Minor’ in the title of our book is an important marker. The Roman province of Asia was only one of the seven Roman provinces within the modern frontiers of Turkey. But it is an elusive name. To us it meant the western province of Roman Turkey, but we later found out that it came into common use only through early Christian writers tracking the journeys of St Paul, and was never an official term during the classical age of the Empire. But we were reassured when a scholar informed us that the word Asia has always meant different things at different times: starting off as the Hittite homeland (Aswiya) in Anatolia before it grew and embraced all of their Bronze Age empire, which stretched across Turkey. Now it embraces a vast continent. So we have stuck to that romantic resonance of Roman Asia Minor, a literary province of the mind.

It was a continual theme of all three of our journeys to chuckle over the way any single city that we explored in Asia Minor held more elegance and enchantment than all the surviving elements of Roman Britain put together. Meanwhile, the cumulative energy of all those Roman bridges, fountains, embankments, gates, walls and tombs we discovered in the countryside – many of them still standing and in use where they had been placed 2,000 years ago – told another story: one of continuity. Our journeys taught us, too, that if the European Union is in any way inspired or modelled on the achievements of the Roman Empire it is marvellously absurd to have excluded the glories of Asia Minor.

Don and I both revere the classical past to an almost embarrassing degree, but we became aware that today’s Turks, in their everyday habits – bathing, eating, relaxing at home – are part of this living tradition. Students of the classical world will glean more from bathing in an Ottoman hamam and then sitting in a Turkish meyhane watching the theatrical arrival of tempting small platters, than from any number of university lectures.

His camera bag would remain buttoned if he observed too much restoration

It was my self-appointed task to get Don to the Roman ruins within Asia Minor that I thought would interest him most in terms of their size, shape, historical importance and state of preservation. We also needed to be at our chosen sites with time to spare, to capture the light of dawn and dusk, with clouds as a bonus. Don was born in 1935, but any age he might wear is shed at these critical hours, when he lives up to his confession: ‘I have just one addiction – photography.’

During our journeys I have noticed how he is inspired by an internal aesthetic, which is attuned to the authenticity of the monument. His camera bag would remain buttoned if he observed too much restoration, or any sign of an excavation trench, or thought we were trespassing on what had once been a domestic space – unless I begged him, saying that it had been mentioned by Homer or walked upon by Aristotle, which is how we fell in love with the Temple of Apollo Smintheus and the Temple of Athena at Assos.

What especially seemed to absorb him was something that had once been very fine but had been weathered by time, that had endured terrifying periods of conflict but had miraculously survived with its spirit intact after centuries of adversity. At times it was as if he was catching a glimpse of his own soul, weathered in ancient stone.

I’m afraid of higher wages

So, Britain has finally awarded itself the real-terms pay rise that the unions would say workers ‘deserve’. This morning’s inflation figures show that the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) is up 6.8 per cent in the year to July. Yesterday’s earnings figures showed that wages grew by 7.8 per cent. So, in other words, the UK workforce as a whole has received a real-term pay rise equivalent to a whole percentage point. The period of falling real incomes is finally over – at least for the majority of earners. Some, of course, will still be seeing falling real wages.

In the absence of productivity growth, any wage rises will turn out to be illusory

But is it really ‘deserved’? A third – and much less commented upon – set of figures was released by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) this week. They showed that productivity per hour worked is up only 0.1 per cent over the past year. In fact, productivity has been pretty static ever since the pandemic. This is the sort of thing that is going to worry the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). A society cannot grow richer unless it can improve output. In the long term, in the absence of productivity growth, any wage rises will turn out to be illusory – they will be cancelled out by inflation, which is nature’s way of ensuring that we cannot get something for nothing.

That is not the only worrying sign. When inflation was on its way up, the MPC, along with many others, comforted itself that ‘core inflation’ – that is when you strip out food and energy prices on the grounds they are supposed to be more volatile – was not rising at the same rate. You can wonder what the point is of an inflation rate which strips out two of the biggest contributions to the cost of living – indeed, you can fiddle around all day to invent new inflation indices which make the economic picture look better: how about creating an IPEEGU (the index of prices excluding everything that is going up)?

But the point is that the ‘core’ inflation index isn’t coming down. At 6.9 per cent it stands exactly where it did in June, and is now higher than CPI. In other words, the conceit that the inflationary surge of the past year is just some one-off adjustment to a post-pandemic supply crunch is bunk. Inflation is now embedded across the economy, and worse, it is feeding into wage rises, bringing us to what looks suspiciously like the beginning of a wages-prices spiral. The Bank of England’s last Monetary Policy Report was predicated on the assumption that annual wage rises will be down to 6 per cent by the end of the year. That is beginning to look like a forlorn hope. Don’t expect interest rates to be coming down any time soon.

Bridge | 19 August 2023

They say a two-way finesse is never a complete guess: there are always clues to be gleaned from the bidding and play. That’s not strictly true, as the great Giorgio Belladonna once demonstrated at a tournament when, after a long think, he turned to a kibitzer and asked him to toss a coin.

But even with nothing concrete to go on, you can often rely on psychological inferences – an untimely hesitation, for instance, or feigned nonchalance from one of the opponents, which, as P. Hal Sims argued, made it far more likely he held the queen. Alan Truscott’s advice was always to play your left-hand opponent for the queen: it can be a dangerous card to lead away from, so that might be one reason he didn’t lead the suit. Personally, I like my friend Gary Bell’s suggestion: finesse into whichever opponent you find less annoying; it’ll hurt less if they win.

There is another excellent way to flush out a queen, which many players overlook.

In a recent duplicate, most Souths were in 3NT. West led the 5♠️ to East’s ♠️J and declarer’s ♠️A. South has eight tricks, and needs a third club, but can’t afford to lose the lead. Many players cashed diamonds to learn more about the distribution. Some cashed a top club in case the queen was singleton. But a couple of experts chose another way: at Trick 2, before giving anything away, they played the ♣️9. It’s hard for West not to cover if he has the ♣️Q. South might be leading from ♣️9x; if he ducks, and East wins the ♣️K, a second finesse will produce three tricks. Even if South has ♣️98, it looks like the ♠️K is the only entry to dummy, so when declarer wins and plays low, East can duck. Bad luck, West – a thoughtful defence can backfire.

How builders plan to get round the Ulez charge

‘What a worry the Ulez must be for you both,’ said a friend with a nod to the pick-up truck parked outside our house.

It was kind of him to wonder. The builder boyfriend drives an old Mitsubishi L200 to work in London every day and like almost every other working man he cannot afford to buy a new vehicle that is Ulez compliant so you would presume he has to pay the charge. But that’s not quite how it’s turning out.

There is no Ulez problem for any Khan supporter who can find an old granny to put in his old car once a week

If I might speak for the working man for a second, because not many seem to be doing that, let me explain with an anecdote from the life of the builder boyfriend, who came home the other day in a buoyant mood to tell me this. He had been working on a large house where he and a plumber were among four or five men retained by a wealthy lady with an electric Audi parked outside.

This lady, who was nice enough, came out of her house as the workmen sat drinking their tea and struck up a conversation on a topic she evidently thought they might find sympathetic of her.

‘I do feel so sorry for you chaps,’ she said, ‘with the Ulez expansion.’ The men kept drinking and said nothing. ‘I suppose you’ll all have to get rid of your old vans now.’

And she glanced at the BB’s black L200 ‘Warrior’ and the plumber’s panel van. And still the men sat quietly drinking their tea.

In the end, the plumber piped up: ‘We ain’t getting rid of nothing, love,’ he said. ‘I can’t afford a new van.’ And the BB shook his head to indicate that neither could he.

‘But then how will you afford to pay this charge?’ said the good lady. And the plumber laughed and said: ‘We ain’t paying it, love. You are.’

It fell to the builder boyfriend to explain to the lady that if they were still on her job in a few weeks’ time, when the Ulez is expanded to all London boroughs, their bills at the end of each week would include a new item. On top of labour and materials, the £12.50 a day Ulez would be added.

For her renovation job, that came to an extra £250 a week at least.

As I understand it, it was no use her wondering if she might get a better deal out of another set of tradesmen. Everyone the BB has spoken to in his world has said the same thing: we’re not buying new vans, and we’re not paying the emissions charge.

This Ulez may well represent a small fightback for the common man, or poetic justice of sorts, or just an ironic turn up for the books. Perhaps you might call it schadenfreude at the expense of the electric Audi drivers who thought it was not something to concern them.

Because they will have to foot the bill.

Of course, you could argue that low-income people will also face the rising cost of getting in tradesmen, but then again, the working classes are more likely to be able to fix their own stuff or get a deal out of a mate.

More specifically, the BB has heard on the QT from his mechanic that poorer people are bringing in their old bangers for MOT as usual as the 29 August deadline approaches, because they are registering them as a car used to drive their old granny.

Sadiq Khan has provided an opt-out, you see. Those who can register a non-compliant car with the DVLA as necessary to transport a disabled friend or relative will be exempt from the charge. He really does think of everything. There is no Ulez problem for any Khan supporter who can find an old granny to put in his old car once a week.

So it does look like Ulez will be hitting the responsible, upstanding professionals who have dutifully gone out and bought expensive electric cars. Those who do not know how to plug a leak or unblock a gutter must now pay £12.50 a day extra to get a working-class oik to come to their rescue in an old van choking black smoke. The builder b will fix any roof in London so long as the owner pays his congestion and Ulez charges. And so far, people have.

There are so few workers who can buy new vehicles that the playing field seems to have been levelled with everyone hiking their rates.

The builder boyfriend and I once bumped into Sadiq Khan at a friend’s party in Richmond. He and his wife and their entourage arrived in a fleet of luxury Range Rovers.

Now the BB has worked out how to survive the Ulez until we leave for Ireland, that doesn’t bother me as much.

The FBI has a problem with Catholics

On board Aello

She was built in 1921, a beautiful wooden ketch that is as graceful to look at as she’s uncomfortable for fat cats accustomed to gin palaces. I’ve sailed her over many years, the last time giving her to my children as I was in plaster having fallen from a balcony in Gstaad. This time it was worse. In fact it was the greatest no-show since Edward VIII skipped his coronation and showed up on the French Riviera instead. Michael Mailer had hinted that some Hollywood floozies were eager to sail around the Greek isles, but arrived empty-handed. The absent floozies were missed, but were immediately replaced by my son and his son, and off we went, four males looking for mates down the Peloponnese coast. Young Taki, aged 17, won hands down, romancing the most beautiful 16-year-old in the whole of Greece, whose grandfather was a friend of mine and whose great-grandfather was a crony of my father. Such are the joys of old age.

Aello’s crew of five was eager, willing and able – there is nothing worse than reluctant, pusillanimous sailors – and there was a surprise right off the bat. The steward Fraser Richardson, a Scot, is a handsome young man who has written a very good screenplay according to Michael Mailer. He told me that his grandmother, Moira Macfadyen, is a loyal and long-time reader of The Spectator. ‘So what else is new?’ answered yours truly. ‘Everyone whose brain hasn’t turned to cheese reads The Speccie.’

With family on board, I decided to act responsibly and in a dignified manner. Once upon a time wild scenes of drunkenness and women-chasing were par for the course. No longer. Our first port of call was Prince Pavlos’s and Princess Marie-Chantal’s villa high up on the island of Spetse, where the Greek royal couple was giving lunch to their five children and their friends. A great breeze, 15 youngsters, very good wine and some beautiful girls made me quickly forget any resolution I had made. Especially after being greeted by Poppy Delevingne as though I were a returning Odysseus. Poppy is among the nicest girls around, and she’s high-stepping it with Pavlos’s Constantine Alexios, a Greek prince with old-style Hollywood looks.

Well-oiled after a lunch that lasted almost until dark, off we sailed across the bay to pay a brief visit to Peter and Lara Livanos, whose two great boats were anchored in front of their seaside mansion. More wine and more stimulating conversation followed. Peter Livanos, the King of LNGs, is a very wise businessman who reads history. The subject we discussed was – duh – China vs the U S of A. Peter does not think that China will use violence to take Taiwan. The latter will fall into Chinese hands like a ripe apple sometime over the next 50 years. Unlike the hamburger eaters who have four, or possibly eight years to make things happen, the undemocratic Chinese have time on their side.

The irony of all this is that even five years ago all of us would have been on Uncle Sam’s side, dismissing the Chinese as robotic slaves of a dictatorship that threatens the world with its ideology. ‘No mas,’ as the boxer Alberto Duran announced when he quit during a fight with Sugar Ray Leonard. Uncle Sam has turned into an intolerant, stoned, cop-hating, woke-loving slob that promotes a culture where thieves and other miscreants are not viewed as criminals, and honest people are deemed to be deserving of being robbed. And it gets a lot worse. The FBI, once upon a time an American institution of incorruptibility and fairness, is now a swamp of left-wing zealots waging war against the Catholic church. The slur against the church is that Catholics are potential domestic terrorists. And where does the info come from? The left-wing Southern Poverty Law Center, a rich pressure group that targets whites and conservatives and one that enjoys great influence in DC.

Who would have believed that in the so-called land of the free the FBI would turn out to wage war against faith in God. LGBTQ apparently has a lot to do with this outrage, working with the Southern Poverty Law Center to besmirch Catholics and what the Catholic church represents. Our own Douglas Murray exposed this in his New York column.

But why am I writing about pre-traumatic Uncle Sam-induced stress disorder and Chino-melancholia when on my last night in Spetse I discovered the greatest bar-dive packed with friends. Pavlos and M.C. were with someone whose parents – both now gone – first befriended the poor little Greek boy in Paris very long ago. The night of their wedding we went to Maxim’s, just the three of us, and it looked like a marriage made in that nice place up above. Alas, it didn’t last. But they had Arkie Busson, the smartest boy of his generation, a terrific skier and Romeo, now in his fifties and a self-made tycoon. We talked about the good old days and health and, as Pavlos now trains hard in karate, the conversation turned to the Musk vs Zuckerberg so-called upcoming fight. I’m not the Delphic Oracle, but it ain’t gonna happen. If it does, my moolah is on Musk. Zuckie has never been hit, and lifting weights and training with real pros does not a fighter make.

But take it from Taki: Arkie would make short work of them both; my money’s on him.

Is it really not safe to extradite someone to Japan?

In November 2015 three men entered a jewellery shop in Tokyo’s upmarket Omotesando district, beat and injured a security guard, smashed a showcase and stole 100 million yen’s (£600,000) worth of goods. The suspects identified by the police fled to the UK, where, after the intercession of Interpol, they were arrested. Japan, unsurprisingly, wants them back. But in the absence of an extradition treaty with the UK it needed to make a special request. Last week, the extradition request for one of the men was turned down – with the court noting that the suspect’s human rights could not be guaranteed by the Japanese criminal justice system.

This is on its face a gross insult to Japan. It is a first world country, G7 member and long-standing partner and ally. Yet apparently it can’t be trusted to provide a fair trial. In particular, the suspect had claimed that if extradited he would be made to confess under duress, and the court appears to have agreed. It is a damning indictment of Japan’s justice system, long criticised for its harshness, inflexibility, and indifference towards the detained. But how true is this characterisation?

Fully, would be the response of Human Rights Watch who just three months ago released a report which may have had a bearing on last week’s judgement. Coming in for particular criticism was the practice of detaining suspects for ‘long and arbitrary periods’ and repeatedly and aggressively interviewing them until a ‘confession’ is extracted. The report has an epigraph from a former prosecutor Nobuo Gohara that summarized its general theme:

‘You are basically held hostage until you give the prosecutors what they want. This is not how a criminal justice system should be working in a healthy country’

The report details iniquities such as abusive interrogations, denial of bail on spurious pretexts, the prohibition on communication with family and friends, and unaccountable and overpowerful prosecutors. An article by David T Johnson in the Asian Journal of Criminology estimates that interrogations in Japan last 30 to 50 times as long as in the US, often in police holding cells (‘a hotbed of wrongful confessions’) rather than detention centres, and cites a report from the former Nissan CEO Carlos Ghon’s lawyer, Takashi Takano, which estimated that there are 1,500 wrongful convictions a year.

Ghosn’s case was illuminating and consequential. In 2019 the former Renault/Nissan/Mitsubishi CEO, who had been arrested on charges of false accounting (and interrogated for 500 hours) escaped from custody in Tokyo claiming that he would ‘no longer be held hostage by a rigged Japanese justice system where guilt is presumed, discrimination is rampant, and basic human rights are denied.’ A UN working group subsequently investigated Japan’s detention system and declared it fundamentally unfair.

The Japanese government dismissed the UN’s opinion as ‘totally unacceptable’, but the reproach undoubtedly stung and poured salt on a suppurating wound. In response to criticism, from within and outside Japan, there were significant reforms in 2019 beefing up suspects’ rights, giving more powers to defence attorneys and mandating the videoing of interrogations – though there is debate as to how fully these measures have been implemented or whether they go far enough.

While there are certainly serious issues with the Japanese criminal justice system a partial defence can be made. Some of the statistics used are misleading. The oft-cited scarily high conviction rate (98 per cent) is often used to suggest that anyone scooped up by the police in connection with a crime is destined for jail regardless of the evidence. In truth the rate is a result of the fact that only strong cases make it to court, with weaker suits dismissed or dealt with at a lower level.

More broadly, imperfect though the Japanese system undoubtedly is, it is probably effective in disincentivising would-be criminals from contemplating a life of crime in the first place – Japan has a remarkably low level of violent crime. To take one example, the strict rules around illegal drugs are a particular success, with strikingly low levels of use meaning the country is spared the massive health, societal and related crime problems endemic in the West. Though the punishment meted out to someone who perhaps on a single occasion smoked marijuana might seem harsh, the message this communicates may well keep people from embarking on a dark and disastrous path. As a deterrent it seems to work. Does our system?

It is interesting that this case has happened at the very moment when Julian Assange is now ‘dangerously close’ to extradition to the US on charges that appear to many to be politically motivated. Assange faces a hellish future in a high security hell hole that would make Japan’s spartan but at least apparently safe prison estate look like a holiday camp. While the charges against the suspect in the Tokyo jewellery heist appear clear, and the evidence (security cameras) apparently substantial, the same can hardly be said of Assange. A campaign to get his extradition stopped has been active for a while now, but there is no sign that the Home Office will relent.

But then we mustn’t offend the Americans, with whom we enjoy a ‘special relationship’.

I’m bored of Disney feminism

It is, I know, a bit early to be thinking about 2024, but to help with the forward planning, here’s a film to avoid next year: the Disney release of its new, non-animated, musical version of Snow White. The original animated version of 1937 was a classic if ever there were one. Stewart Steven, the late editor of the Evening Standard, remembered seeing it as a boy when it was released: ‘I was completely terrified’, he told me, speaking for a generation of children. It was a triumph of animation; the songs were terrific – the seven dwarves’ ‘Hi Ho, Hi Ho’ is immortal; and the episode where the princess, fleeing the huntsman through the trees, is tormented by clinging branches and malevolent eyes is fearful. It’s just a pity that most of us now see it on a small screen.

Disney provides a consumerist vista of hyper-femininity which even I think is toxic

Skipping right through to the present day, Disney’s new version has already attracted uncharitable ridicule for its sensitive treatment of the seven members of the vertically challenged community: ‘To avoid reinforcing stereotypes from the original animated film, we are taking a different approach with these seven characters and have been consulting with members of the dwarfism community’, it announced, to barely stifled sniggers across the globe.

But the grimness – as in grim, not Grimm– doesn’t stop there. Rachel Zegler and Gal Gadot’s interview on the new feminist take on Snow White makes for dispiriting viewing. Gal Gadot, who is the wicked Stepmother, insists that Snow White is ‘not going to be saved by the prince’. I think we’re meant to cheer at that point.

Snow White, i.e., Rachel Zegler, who resembles the original in being a bit vertically challenged herself, agreed. ‘She (Snow White) is not dreaming about true love; she’s dreaming about being the leader she knows she can be, the leader her late father told her she could be if is was fearless brave, fair and true. The cartoon was made 85 years ago and it’s extremely dated when it comes to the idea of women being in roles of power and what a woman is fit for in the world. And when it came to the reimagining of the role, Snow White has to learn a lot of lessons about coming into her own power before she can come into power over a kingdom.’

You know, this stuff could have been scripted by Meghan Markle, Duchess of Sussex, who had her own version of riding off on a prince’s horse and did very nicely out of it. Does everyone in LA talk this sort of rubbish? This, from a company which makes a fortune – and I mean a fortune – by fleecing the parents of little girls with overpriced princess outfits (check out the prices at the online store and be prepared to feel a little faint). Disney provides a consumerist vista of hyper-femininity which even I think is toxic. But routinely dissing the concept of true love and a story ending in marriage is, I’d say, one reason for our present demographic crisis.

Granted, the original Disney version of the story was not true to the original Grimms’s tale, like most Disney variants. Neither, come to that, were most of the versions of the story read by English readers, who got an expurgated version served up by one Edgar Taylor – a Norfolk lawyer turned translator. No matter.

But if Disney really wanted to scare the life out of us with a raw version of Snow White, it could do worse than return to the original – and there’s a useful translation of the tales by the Grimm Brothers expert, Jack Zikes. That differs in several respects from the Disney version. The wicked stepmother has three attempts at Snow White’s life, not one. She is punished at the end of the story by being forced to dance to her death in red hot shoes – I would so love to see Gal Gadot performing that feat. And most chillingly, in at least one early variant of the story, it is not the wicked stepmother who sets out to kill Snow White out of envy of her beauty, but her own mother. Try sucking on that.

This isn’t the first cinematic travesty of the Grimm stories – Jack Zikes’ book Grimm Legacies documents a succession of rubbish film adaptations – but it’s a sad one because the original was such a delight. The mystery is why we even bother watching contemporary Disney films. The last enjoyable one, I’d say, was the remake of Beauty and the Beast with, of all people, Emma Watson. Or the animated version.

As I say, you can save a couple of hours of your life by not watching this frightful film next year. You’re so welcome.

Men, please take off your necklaces

Vogue recently announced that Harry Styles had travelled to Normandy where he had his portrait painted by the British artist David Hockney. It wasn’t the meeting of two cultural icons that caught my attention, or the fact that the unphased Hockney described the world’s biggest popstar as ‘just another person that came into the studio’, but instead it was Styles’s sartorial choices.

The gym bros I went to school with are downing a protein shake in pretty pearl necklaces

Styles has long been associated with the gender-bending fashion trend we have seen in recent years. From sheer pussybow blouses, dangly earrings, extravagant tulle dresses and what has become his go-to accessory, a pearl necklace, Styles is loud and proud about embracing femininity. He can get away with it. Not just because he’s a superstar but because he is beautiful and beautiful people can get away with almost anything.

Styles is undeniably a good-looking man. Show me someone that disagrees and I’ll show you a liar. But sitting in a wicker chair, face to face with David Hockney, in a bright striped cardigan and a chunky pearl necklace, Styles was dressed more like a primary school teacher than a rockstar. Of course, men wearing jewellery isn’t new. Blokes in ancient Egypt wore jewellery. And King Henry VIII’s collection would have made Kim Kardashian weep with envy. But never before has male ornamentation gone so mainstream. It’s inescapable, from established Hollywood royalty like Brad Pitt to actual royalty: one of Prince Harry’s complaints about his brother and future King was that he broke his necklace in a physical altercation.

In 2015, men’s fashion week was launched for the first time in New York and since then we have seen an increase in gender fluidity. After all, no one wants to see men in suits walk up and down the catwalk in cities across the world twice a year. Now, though, men’s jewellery is no longer reserved for Haute couture shows.

Styles was the first male cover star of American Vogue on the cover he donned a floor-length gown. Two years later Timothée Chalamet became the first male cover star for British Vogue. Following in Styles’s footsteps he too wore a pearl necklace, one that was usually favoured by 80-year-old widows at funerals. Someone needs to tell these boys that it really doesn’t look good.

When Ziggy Stardust pioneered sexual and sartorial fluidity in the 1970s, it was an act of rebellion against the establishment. Now it’s become so mainstream that you can get a pack of two pearl necklaces for men for £9.99 in H&M. The gym bros I went to school with are downing a protein shake in pretty pearl necklaces. The fashion designers and their muses are, of course, expected to push boundaries – but we have reached the final frontier – there are no more boundaries left. The lines have all been crossed. So, eventually, the pendulum will swing back. Who knows what that will look like; maybe we’ll see Sam Smith in a suit and tie. But here’s hoping the men will hang up their necklaces for good.

Punk’s fake history

If you were born after 1970 and don’t remember punk, you’ve almost certainly been misled by people who do. You’ve probably been told – through countless paean-to-punk retrospectives, documentaries and newspaper culture pages – that it was a glorious, anarchic revolution that swept all before it. I can tell you first-hand that it wasn’t.

Punk was as middle-class as a Labrador in a Volvo. It was invariably the posher kids who abandoned Pink Floyd, Genesis and Yes

Far from being hugely influential, punk was a passing fad that made little impression on the charts and left the lasting legacy of a spent firework. Only one punk single could be described as a big hit: The Sex Pistols’s fabulously obnoxious ‘God Save the Queen’ which shot to number two on the week of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee.

However, the Pistols didn’t share that top ten with any other spiky-haired renegades. Instead they vied for sales with Kenny Rogers, Barbra Streisand and The Muppets – any of whom can still make them look musically and culturally trivial. So why are punk’s false glories still mythologised into falsity? How has it remained in the cultural colander when far more popular genres have drained away?

Quite simple: punk was as middle-class as a Labrador in a Volvo. It was invariably the posher kids who abandoned Pink Floyd, Genesis and Yes for The Sex Pistols and The Clash. After university, many ex-punks went on to become writers, documentary makers or cultural commentators, re-writing history to fit their own narratives.

History, as we all know, is written by the victors and this little clerisy – educated and borderline bougie – was always going to be the victors. A typical example would be a provincial dweeb from a comfortable background who was a shy and misunderstood loner until punk supplied his salvation. Suddenly liberated by a sense of rebellion and a few safety pins, he pledged his undying allegiance to The Damned.

Unfortunately, ‘undying’ has proved to be the operative word because – brace yourselves – it won’t be long before there’s another BBC commemoration of the fabled punk explosion. It’ll no doubt feature the assertion that around 1977, popular music was practically dead until punk jolted it to back to life with its three-chord simplicity and electrifying brilliance.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The singles charts at the time were a cornucopia of fantastic 45s like David Bowie’s Sound and Vision, Don’t Leave Me This Way by Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes and Exodus by Bob Marley. Though the biggest hit in the summer of 1977, laughably labelled ‘The Summer of Punk’, was Donna Summer’s I Feel Love. Phenomenally influential, I Feel Love topped the charts for five weeks and shaped the sound of dance music for the next 40 years.

Julie Burchill succinctly described punk as the most ‘white, male and asexual’ genre of music ever made. So Donna Summer – black, female and sexy – was of little interest to the punkily inclined. They were fooled and besotted by The Clash, a band formed by a public schoolboy called John Mellor who’d seen what the Sex Pistols were doing and decided to Xerox that for his own band.

Taking his cue from ‘Gary Glitter’ and ‘Alvin Stardust’, John gave himself the equally silly name of ‘Joe Strummer’ and that wasn’t the only cue he took. The cover of The Clash’s third album, London Calling, is identical to the cover of Elvis Presley’s first one. But it was when they turned their attention to reggae that The Clash became truly embarrassing. If you’re offended by cultural appropriation, don’t listen to their execrable version of Police & Thieves. It’s on a par with The Black and White Minstrels singing Ol’ Man River but mercifully, not too many people would have heard it. Most were too busy listening to Hotel California, Saturday Night Fever and Songs in the Key of Life, all infinitely more popular than punk in 1977.

The reality of the 1970s bears little resemblance to the way it’s now portrayed. Two years after the Bay City Rollers, The Sex Pistols were another manufactured boy band, shrewdly groomed by a ruthless manager – the Bay City Rollers with attitude. Don’t get me wrong, I liked that attitude. There was an authenticity to their phlegm-flecked malevolence which meant they attracted frenzied media attention. And it’s the intensity of that attention which forms the basis of those countless misleading punk retrospectives.

Those who make them are now probably too young to remember punk and base their opinions on previous documentaries, so the insufferable punk bandwagon rolls on. We’ll have to endure more falsehoods about its popularity and lasting influence when neither claim holds up. Compared with the joyous attractions of disco, funk and reggae, punk was often joyless, elitist and too often about moralising rather than music. Ideal for the middle classes from where most moralising comes.

Punk flashed for a brief period – and it was pretty vibrant. Though if you’re looking for musical and cultural significance, trust me, it was also pretty vacant.

Captain Tom’s daughter does it again

It’s an ITV drama just waiting to be filmed. The saga surrounding the family of the late Captain Sir Tom Moore has now taken a fresh twist, following a Newsnight investigation. The programme alleges that Moore’s daughter, Hannah Ingram-Moore, was paid thousands of pounds via her family company for appearances in connection with her late father’s charity.

In 2021 and 2022, she helped judge awards ceremonies which heavily featured the Captain Tom Foundation charity. Promotional clips suggested she was there to represent the charity but her fee was paid not to the Foundation but to Ingram-Moore’s family company instead. Surely shome mistake?

The awards ceremony in question was the Virgin Media O2 Captain Tom Foundation Connector Awards, which included the name of the charity and the charity’s logo on its awards plaques. At the time Ingram-Moore was the charity’s interim chief executive on an annual salary of £85,000. However her appearance fee was paid not to the Captain Tom Foundation but to Maytrix Group, a company owned by Ingram-Moore and her husband, Colin.

Given a right of reply by the BBC, Hannah Ingam-Moore offered a gem of a response in an email about the matter, saying ‘You are awful. It’s a total lie.’ Six minutes later she added: ‘Apologies. That reply was for a scammer who has been creating havoc’. The Beeb say she hasn’t responded to questions about the money received by her company.

It comes amid an ongoing year-long investigation by the Charity Commission into potential conflicts of interest between the charity and the Ingram-Moores’ businesses. Don’t expect Hannah to start doing laps of her garden to pay back Virgin’s money any time soon…

Shades of Kafka: Open Up, by Thomas Morris, reviewed

Thomas Morris has a knack of writing about ordinary things in an unsettling way and unsettling things in an ordinary way. He described his debut collection of ten stories set in Caerphilly, We Don’t Know What We’re Doing, as ‘realism with a kink’. Open Up, a slimmer second offering of five stories, amps up the Kafka. One is narrated by a seahorse, another by a vampire. Morris’s attitude towards his characters remains central: while displaying their darkest secrets, you sense he’s on their side. Here, the narrators are all male. From a young boy to a thirtysomething, they negotiate masculinity’s contradictory demands, accused of being distant, passive and unambitious.

Individually, the stories offer texture in tone and place; collectively, they revolve around connection and the wish to belong. In ‘Wales’, a boy delights in a football match with his father, unaware of what’s around the corner. The 5ft 3in office worker in ‘Little Wizard’, named Big Mike, is as nonplussed about gender politics as he is heartbroken about his height. A passive holidaygoer experiences meltdown in Croatia with his girlfriend in ‘Passenger’. Loss and parenthood are explored in ‘Aberkariad’. And an Adrian Mole-like ‘psi-vamp’ who sucks energy obtains fangs for his 21st in ‘Birthday Teeth’.

Short fiction can perform magic tricks with space and time, and Morris has mastered this. Casting his net of influences wide, he also finds ways to add dimension that preclude the written word. On Spotify and YouTube, a playlist of 15 songs, from Beck to Philip Glass, which Morris listened to while writing ‘Aberkariad’ has been uploaded, taking the same title as the story. He cites the American writer A.M. Homes as an influence, and her coolly detached tones emerge in ‘Passenger’, one of the collection’s highlights.

Not everything hangs together. Some of the stories’ endings aren’t perfect and ‘Birthday Teeth’ lacks bite. The mockumentary series What We Do in the Shadows covered the tragi-comic vamp niche first, monopolising it for a good while. It’s best to know when to run with your conceit and when to concede defeat.

The literary landscape is strewn with works bloated with fat and puff. (We’ll call them ‘McBooks’.) Morris was the editor of Dublin’s literary magazine The Stinging Fly from 2014 to 2016, so understands the stringency of short fiction: namely, that there’s nowhere to hide. Andrew Motion years ago urged me to produce prose that ‘looks like water yet tastes like gin’. At his canniest, Morris writes in that spirit.

In search of Jeanne Duval: The Baudelaire Fractal, by Lisa Robertson, reviewed

The shared etymology of the words ‘text’, ‘textile’ and ‘texture’ – from the Latin verb textere, ‘to weave’ – has long been a fertile subject, its thread running through the work of theorists such as Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, Gilles Deleuze (from whom one of the epigraphs for this book is taken) and others. But this now critical commonplace provides a helpful entry point to the Canadian poet Lisa Robertson’s sometimes evasive first novel The Baudelaire Fractal, a work obsessed with textiles, tailoring, intertextuality and the woven physicality of language. The word ‘novel’ seems only really appropriate in its adjectival sense.

It tells the story of Hazel Brown, a woman who wakes one morning, following her delivery of a lecture on ‘wandering, tailoring, idleness and doubt,’ in a hotel in Vancouver, to ‘the bodily recognition that I had become the author of the complete works of Baudelaire’. Or ‘perhaps it is more precise to say that all at once, unbidden, I received Baudelairean authorship, or that I found it within myself’. Now in middle age, she sets about her task: ‘to re-enter, by means of sentences, the course of my early apprenticeship… to make a story about the total implausibility of girlhood’.

The plot has a whiff of magical realism, via Borges, but really it evades genre or lineage, just as Jeanne Duval – Baudelaire’s muse, and one of the two women with whom the narrator is interested – ‘doesn’t offer herself to an interpretation’. And Duval does provide something of a cipher for the novel; it is less about Baudelaire than about his representation of his female subject, or about the absence at the heart of those representations, as in Gustave Courbet’s ‘The Artist’s Studio’, in which Duval was painted beside the poet, then painted over, before, ‘many years later, as if in a mystic material refusal of this obliteration,’ she became visible again.

The narrator, too, insists on her presence in the male world of 19th-century poetry, where even culture is ‘owned’. ‘I needed to write in order to make a site for my body,’ she explains: ‘I, a girl, exultant, crossed into the room of sentences.’ Her aim: ‘To free the sentence from literature.’ And following Cixous and Deleuze, writing and the body – and therefore the trappings of the body, fashions and fabric – are indissolubly linked, dialectic, porous: ‘I would be the girl of my notion of literature… My outfits and their compositions were experiments in syntax and diction.’

This synthesis of textures, of meditations on tailoring and art, and ‘the immense, silent legend of any girl’s life,’ is ambitious, clever and often beautiful and pressing. If often defiant of categorisation, as Jeanne Duval defied interpretation in her portrait, Robertson’s first foray into fiction is a timely reminder that ‘a sentence can be a blade’.

The man who loves volcanoes

Being a volcanologist demands a quiverful of skills. You need to be in command of multiple branches of science, including geophysics, geochemistry and seismology. But you must also understand people for whom science matters less than sorcery: people living near volcanoes, for whom they are sacred places, homes to ancestors, sites of miracles, mountains where God’s intervention in human affairs is made manifest in ash, fumes and flame. And you have to be brave. When it comes to studying volcanoes, risk and reward go hand in hand. So a volcanologist must be willing to peer over the edge of a crater, breathing in smoke ‘inconvenient to respiration’, crying acid tears. On Mount Erebus, Clive Oppenheimer tells us, this means looking down on a vat of molten lava throwing up red-hot bubbles the size of the cupola of St Paul’s cathedral, which distend, then pop, flinging dollops over the crater’s rim. Thudding to the ground, they look like the turds of giants.

Mount Paektu is worshipped by North and South Koreans, who invest it with hopes of eventual reunification

A professor of volcanology at Cambridge, Oppenheimer is nonchalant about what it was, 30 years ago, that drew him to this line of work. ‘I turned to volcanoes because I’d never had a better idea’, he says – as if he might just as easily have become an accountant or a traffic warden. But after a gap year spent among the volcanoes of Indonesia, he was captivated. His speciality is spectroscopy: measuring the proportion of different gases – water vapour, carbon dioxide and sulphur – in volcanic emissions. One Japanese chemist, Sadao Matsuo, has called volcanic gas ‘a telegram from the Earth’s interior’. Correctly interpreted, it can signal what a volcano might do next. Oppenheimer has also spent time investigating the possibility of taking the temperature of a volcano from space. But ‘spaceborne imagers’, he believes, ‘have a long way to go before they eclipse a trained field volcanologist huffing and puffing up and down the mountain on foot’.

So fieldwork is what he loves. He has studied more than 100 volcanoes, and he feels a kinship with them. Not only have most of them existed on Earth much longer than human beings, but our ‘fleshly inventories’ are the same – carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur. They are anthropomorphic. Flying over the Tibesti region of northwest Chad, he calls out, against the roar of the plane engines, the names of the volcanoes he is about to visit – Emi Koussi, Tarso Yega, Pic Toussidé – and feels ‘delirious with excitement’. He calls Erebus ‘my muse’; as he is airlifted away from it, he feels ‘the heartache of leaving a lover’.

This may sound like a private passion, but Oppenheimer’s work is profoundly altruistic. Most of us reading his book will never have been experienced worse inconvenience from a volcano than from Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, which erupted in 2010, covering our windscreens with ash. But woven through Oppenheimer’s narrative are eye-stretching accounts of the tragedy active volcanoes can wreak on the lives of the billion or so people in the world settled within 50 miles of them. In spring 1815 Mount Tambora, on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, erupted, and ‘liquid fire’ and a ‘violent whirlwind’ brought ‘down nearly every house in the village… tearing up by the roots the largest trees and carrying them into the air, together with men, horses, cattle’. Twelve thousand people were instantly annihilated, and over the following months many tens of thousands more died from starvation and disease. Roadsides were littered with corpses. Parents sold their children to slave traders to buy rice.

It’s Oppenheimer’s responsibility to try to predict eruptions, and so minimise catastrophe. But he is also an ambassador for volcanoes, determined to demonstrate that they mean ‘more than menace and calamity’. It won’t surprise you that heat trapped from them yields significant fractions of national supply in countries including Kenya, Iceland, the Philippines and New Zealand. But did you know that sulphur blasted by volcanoes into the stratosphere plays a vital part in cooling the planet? And they can help promote political harmony. Oppenheimer devotes one gripping chapter to his work on Mount Paektu, worshipped by North and South Koreans, both of whom invest it with hopes of eventual reunification.

Just occasionally he allows us to glimpse him back in the library in Cambridge, seeking out volcanoes in Pliny’s Natural History or the medieval Chronicon Scotorum. But any reader in doubt about the depth of academic research that has gone into Mountains of Fire needs simply to turn to his notes and references: nearly 100 pages of them. Wisely, he has consigned them to the end of the book. Not a single footnote clutters the main text or distracts from what reads, very often, like a thriller. Perhaps one final attribute of a volcanologist is that he should be a good storyteller. Oppenheimer is better than good. This is terrific.

The ‘historic’ national dishes which turn out to be artful PR exercises

In 1889, Raffaele Esposito, the owner of a pizzeria on the edge of Naples’s Spanish Quarter, delivered three pizzas to Queen Margherita, including one of his own invention with tomatoes, mozzarella and basil, their colours taken together resembling the Tricolore. The Italian queen loved the pizza, and Esposito duly named it after her. In that restaurant today hangs a document from the royal household, dated 1889, declaring the pizzas made by Esposito to be found excellent by the queen.

And so was born the Pizza Margherita, a dish now synonymous with Naples. The queen’s seal of approval in the wake of Italian unification, which had proved difficult for Naples, came to represent the embracing by the governing royal family of an impoverished city by way of their cheapest street food. It showed the royals to be down to earth, and the Neapolitans to be part of a larger Italian nation.

There is no evidence of Queen Margherita ever trying Neapolitan pizzas, let alone endorsing them

It’s a good story, but it’s also little more than that. The ‘custom-made’ patriotically coloured pizza was well known before 1899, the pizzaiolo in question was not the celebrated chef he is now made out to be, and there is no evidence of the queen trying these pizzas, let alone endorsing them. But that hasn’t stopped the Margherita becoming something that has put Naples on the culinary map, a place which people travel to just to taste authentic pizza. And it doesn’t mean that proper Neapolitan pizza isn’t exceptional. So does it matter if it’s founded on an urban legend?

In National Dish, Anya von Bremzen sets out to understand the link between food and national identity, and what symbolic dishes can tell us about national cultures. ‘We have a compulsion to tie food to place,’ she says. She travels across six countries (France, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Mexico and Japan) in an attempt to unpick the belonging, pride, unification, essentialism and political manipulation that go into their emblematic dishes. As well as pizza and pasta in Naples, she tries to find authentic pot-au-feuin France, the meaning of ramen and rice in Tokyo, the origin of tapas in Seville, the future of mole and tortilla in Oaxaca, and the significance of meze in Istanbul.

Many of these dishes have been granted Unesco’s intangible cultural heritage status, an acknowledgment that there is something distinctive about a way of cooking or eating that is inextricably associated with a geographical place and people. The ‘gastronomic meal of the French’ has been recognised as a ‘marker of cultural identity’, as have Washoku, the traditional dietary cultures of Japan, and the art of making a proper Neapolitan pizza. In 2017, Azerbaijan was granted the status for its ‘dolma-making and sharing tradition’, which caused consternation in Turkey and Armenia, countries that also lay claim to the stuffed leaves.

Of course, these kind of statuses, which are designed to preserve cultural heritage, give rise to questions of ownership and identity. ‘As the world becomes even more liquid, we argue about culinary appropriation and cultural ownership, seeking anchor and comfort in the mantras of authenticity, terroir and heritage,’ von Bremzen writes. The initial questions she asks are simple ones: how and why do dishes get anointed as ‘national’, and what is the connection between cuisine and country?

She approaches the exercise with understandable scepticism. She grew up in Soviet Russia before fleeing to the US with her mother when she was ten, so she is no stranger to top-down nation-building and knows the political power that food can have in this.

The scepticism is well-placed. After her pursuit of the cult of pot-au-feu is mostly received with Gallic shrugs, and pizza’s origin story turns out to be ‘fakelore’, she discovers that tapas is also a recent invention, only entering the dictionary in 1936 and primarily used as a way to entice tourists. In Tokyo, she finds that the popularity of ramen was manufactured in order to use up US wheat flour imports during the post-1945 occupation. The Japanese ministry of health and welfare ran campaigns to push wheat, and therefore noodles: ‘Parents who feed their children solely white rice are dooming them to a life of idiocy.’ What we think of as intrinsically Japanese is a recent adoption and a product of propaganda.

This set-up feels as though National Dish could be a particular type of travelogue – a food memoir, with some local cookery lessons and nice anecdotes about the passion people have for traditional dishes included, plus a bit of smugness when their myths are debunked one by one. But that’s not what it is. For all its dry wit and vivid descriptions of puttanesca and tortillas, this is a serious book – a skilful blend of academic research and lived experience. It’s a sparklingly intelligent examination of, and a meditation on, the interplay of cooking and identity.

If you’re looking to connect food to identity, Seville provides a perfect illustration. ‘Jamon is the symbol of Spain,’ a ham vendor tells her. She duly visits producers, learns about the craft and tradition of grazing pigs and hanging hams and eats quantities of the ‘slow release endorphin-bomb’ that is ‘pure pleasure’. But it’s never that simple. It is inescapable, she learns, that the ‘cultivation of Iberian ham is tied to… the triumph of Christianity over Islam’. Pork products were used during the Inquisition to root out those who had not truly converted from Judaism or Islam: cooking pots were examined and reactions to bacon scrutinised, with a wrinkled nose at rendering lard enough to alert suspicions. And, of course, the consequences were grave.

That jamon simultaneously inspires national pride becomes central to von Bremzen’s understanding of national dishes. When we hear simple, neat stories about the national importance of a dish, they are usually hiding something. But problematic histories don’t necessarily negate the cultural value of the dish. The two can coexist. ‘Jamon, it’s muy nuestro,’ says one of the guides – ‘so ours’.