-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Red Wall voters prefer a pint with Starmer over Sunak

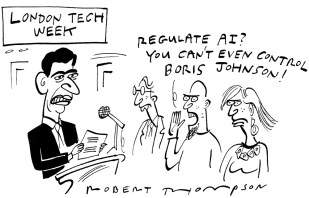

Nicola arrested, Boris now seatless, Nadine’s on the warpath and the Tories are in the mire. These days life seems pretty sweet if you’re Keir Starmer. You can even U-turn on your flagship policy on the Today programme and have it completely forgotten about by the time of the Six O’Clock news. And now a new survey commissioned by Mr S brings more cheer for the Labour leader.

Starmer’s first priority upon replacing Corbyn – other than tackling antisemitism – was winning back the Red Wall and it seems his efforts have not been in vain. A new poll for The Spectator by Redfield and Wilton of 1,200 voters shows that if offered the choice of a pint with the two main party leaders, a third (32 per cent) would prefer Keir Starmer with just one in five (20 per cent) opting for Rishi Sunak. Ouch.

Some 37 per cent trust Labour the most to represent the interests of ‘the North’ – compared to just 15 per cent who plump the Tories. As for the Tories much-vaunted promises in 2019: 56 per cent of Red Wall voters say they ‘do not trust all’ the Conservatives to ‘level up’ the area where they live. A whopping 63 per cent do not feel like the government has been making a clear effort to ‘level up’ their area. And when asked to judge the success of ‘levelling up’, some 47 per cent say it has been a failure – four times as many as the 12 per cent who describe it as a ‘success.’

Enjoy that beer Keir – it might even go well with a curry…

Boris Johnson took us for fools. Now we have proof

No one wants to talk about the pandemic anymore. Not even partygate. Understandably so: we’ve all put hard work into suppressing and burying miserable memories over that two-year period. Why dredge it all back up?

But as one of the people in this country who still deeply cares about partygate – the hypocrisy of it, the abuse of power – I simply want to say that today’s report from the Privileges Committee into whether Boris Johnson misled parliament is remarkable. It’s a delivery of justice that the Sue Gray report wasn’t: one which some of us have quietly been holding out for.

If you don’t have hours today to go through the full 30,000 words published on this inquiry and its findings, I’d highly recommend taking a look at pages 14 to 32. This is the breakdown of six specific gatherings, what happened at them, and what Boris Johnson can be assumed to have known at the time (he attended five of the six). It is methodical work. We are given exactly what the law was at the time. We are given exactly what ministers were telling the public to do in the days around these events. And then we are given more details than we’ve ever had before in one place, about the behaviour of those who were crafting and setting these laws.

We cannot erase what happened, what we were forced to do

It’s painful stuff for Johnson: his testimony to the committee is presented and countered with a host of evidence from other No.10 staff and officials, who often directly refuted Johnson’s claims that these parties were legal or within the guidance. This starts right from the beginning of the lockdown saga. The first party, on 20 May 2020 in the garden, is reported as obviously rule-breaking to the majority of invitees: ‘So many people who were unhappy about the party that they were not going to go,’ explaining why 40 people showed up from a 200-person invite list.

The supporting evidence only gets worse: ‘Wine time Fridays continued throughout’, ‘operational notes’ were sent around to ‘be mindful of the cameras outside the door.’ To say this doesn’t feel like fresh news would be exactly right. We witnessed all this first hand back in 2021 – ministers rolling into No.10 masked up, taking them off as soon as they were inside. We have known for years it was all for show – that the rules inside places like No.10, across Whitehall even, were different for everyone else.

Watch closely. Here’s Matt Hancock wears his mask outside in the fresh air, walking alone. But as he enters a communal area of No10, which is an office full of people, he rips it off his face.

— Bernie's Tweets (@BernieSpofforth) April 16, 2021

The hypocrisy and lies need to stop! #Covid #COVID19 pic.twitter.com/EcEIRJXyLF

That’s not unique about today’s report. It’s not remarkable because of these extra little details about which we already suspected or knew: rather, it finally calls time on Johnson’s repeated insistence that this was all in the rules.

This has been the most egregious aspect of partygate: not that some MPs and their staff broke some rules (they were not easy to follow), but that the public has been told repeatedly that such behaviour was totally fine all along. If you were having a hard, if not impossible, time with lockdowns, you clearly misunderstood the rules. Drinks in the garden? Good to go, so long as you chat a bit about work. Leaving parties? ‘That is up to organisations,’ said Johnson, ‘to decide how they are going to implement the guidance.’ It was not up to organisations – it was not up to individuals – to make any of these decisions. They were made for us and monitored by the police.

We don’t need to dwell on the lockdowns: goodness knows the public’s mental health has been affected enough. But we cannot erase what happened, what we were forced to do, and Johnson’s attempt to defend himself politically has risked, for over a year now, doing just that. The public did not misinterpret the rules and give themselves harsher lockdowns than necessary. They understood the rules perfectly: so they saw no one, did nothing, cancelled life plans and steered clear of park benches.

And, it seems, Boris Johnson understood them too. He just didn’t think they applied to him and his people in the same way. As of today, that is less up for debate. Indeed, it’s now on the record.

Tory MP: ‘Put Boris in the stocks’

The Privileges Committee report is out today and the reaction is just what you’d expect. Nadine Dorries has taken to Twitter, declaring that any Conservative who votes for the report ‘is fundamentally not a Conservative’ and threatening deselections for those who do. Brendan Clarke-Smith has attacked its ‘spiteful, vindictive and overreaching conclusions’; Paul Bristow claims that ‘few are brave enough’ to admit that they ‘clearly go way too far.’

But Steerpike’s favourite response to all of this is that offered by close Boris ally Sir James Duddridge. He sarcastically offered an elegant solution to Johnson’s woes – one that might even enjoy Rishi Sunak’s report. Duddridge tweeted earlier today:

Why not go the full way, put Boris in the stocks and provide rotten food to throw at him. Moving him around the marginals, so the country could share in the humiliation.

And they said the next manifesto would lack popular policies…

Can hydrogen help us reach net zero?

Rarely a week goes by in politics without a reminder of the Conservatives’ ambitions to hit net zero by 2050. But how well do they understand the path to get there? Amidst the barrage of funding announcements and energy strategies, there remain outstanding questions about the road ahead – and one of the most persistent is around the role of hydrogen.

To its advocates, this abundant chemical element could be the key to weaning large economies off their dependence on natural gas, providing a reliable and greener power source that can be deployed at scale. Yet to its doubters, the hydrogen dream remains inefficient and impractical – rendering it a costly distraction from the real decarbonisation challenge.

When it came to investment, there was one clear impediment: hydrogen was still very expensive to generate

For its part, the Conservative government has attempted to keep its options open: announcing funding packages for a series of discrete hydrogen trials, while pressing ahead with electrification en masse. But had they backed the wrong horse? To find out, The Spectator assembled a panel of experts and industry voices at our inaugural energy summit, tasked with unpacking the great hydrogen question.

‘We see hydrogen as a tremendous opportunity, but a very specific one,’ said Lord Callanan, a former Conservative MEP and now Rishi Sunak’s minister for energy efficiency. ‘We are interested in hydrogen as an energy source for those large industries that can’t necessarily be electrified, for example. We are also doing some limited trials to explore how it can be used in heating – but that side of things is much less guaranteed.’

It is certainly true there are no guarantees. But that hadn’t dampened the excitement amongst those who believed hydrogen could replace gas – allowing us to power homes and businesses without having to install potentially unreliable heat pumps. Jake Tudge, corporate affairs director for Britain’s gas grid, National Gas (who sponsored the event), was happy to make the case.

‘I think when you talk about hydrogen, you have to start by talking about natural gas,’ he said. ‘The gas network comprises some 8,000 kilometres of high-pressure pipeline, which go right across the country. We currently use that to heat 23 million homes and fuel over 500,000 businesses.’ That leads to an obvious question: what if that same network could be adapted to run on hydrogen instead?

While a wholesale conversion to hydrogen might be a moonshot prospect for now, Jake Tudge explained how the gas sector was already testing the potential for ‘blending’. As its name suggests, this process involved supplying end users with a blended supply of hydrogen and gas (currently around 20 per cent hydrogen to 80 per cent gas).

‘We’ve actually run some trials doing just that,’ he said. ‘Afterwards the local distribution network asked people what they thought, and the overwhelming consensus was that there was no change whatsoever,’ he said. Like others in the sector, National Gas was now encouraging the government to look at building on these trials to explore the wider use of hydrogen.

At the other end of the spectrum was the industrial case for hydrogen: namely the idea that this less carbon-intensive fuel source could be used to power things like heavy industry and shipping. But as James Richardson, chief economist at the National Infrastructure Commission, explained, this was likely to be limited to specific industrial clusters – at least for the time being.

‘The first thing you need to do is build more pipes, as you can’t use those that are already being used to supply gas,’ he said. This was what was happening, he added, at the industrial clusters at Teesside and Merseyside. ‘Hydrogen is being created by stripping the carbon off natural gas – and storing that underground – and then it is being pumped to large industrial users in the clusters.’

Like most major infrastructure projects, though, the plans would require billions of pounds in investment. And when it came to investment, there was one clear impediment: hydrogen was still very expensive to generate. That might not have stopped the White House from subsidising hydrogen producers via the gargantuan Inflation Reduction Act, but Whitehall was signalling more caution.

‘Value for money is always going to be a key metric when it comes to investment,’ said Jake Tudge. ‘But value for money can change over time, as we’ve seen over the past year. Look at the criticism that George Osborne faced when he signed the contracts for the Hinkley nuclear power plant, for example. People said it was bad value for money. But they wouldn’t say that now.’

For Vicky Parker, the head of PwC UK’s power and utilities team, it was important to avoid being overly pessimistic about new technologies. ‘I remember talking to financiers when we were first looking at offshore wind and there was a lot of scepticism that it would never get off the ground,’ she said. Yet two decades later the industry was more than commercially viable, thanks, in part, to those who had the courage to stick to their guns.

Yet wind power had only taken off after the government had committed its initial investment. So would it be doing the same with hydrogen? ‘If we’re going to get the industry kickstarted, that support has to come from somewhere, whether that’s from general taxation or energy bills,’ said Lord Callanan.

Was that a hint, then, that the government might be about to move forward on the mooted hydrogen levy on energy bills to help subsidise heavy industry projects like those on Teesside and Merseyside? It was an idea that had reportedly found favour with energy secretary Grant Shapps – yet the Conservatives (and Lord Callanan) remained tight-lipped.

On the question of whether hydrogen will soon be flowing to our homes, the minister was more upfront. ‘To my mind it is very clear: the most efficient way of generating heat from electricity is from heat pumps,’ he said. ‘That isn’t to say there won’t be a role for hydrogen, but the vast majority will come from electrification.’ Perhaps those boilers will be coming out after all, then.

Let’s not follow Boris down his path as ‘Britain’s Trump’

The Commons privileges committee report into the conduct of Boris Johnson is completely damning. All the kerfuffle about whether the committee was justified in devising a new intermediate category of mendacity defined as ‘recklessly misleading parliament’ turns out to be irrelevant.

The entire seven-strong committee, including the four Tory members on it, have found that Johnson deliberately misled parliament on multiple fronts. Johnson’s dissembling and purveying of falsehoods while prime minister is judged so serious that, had the blond bombshell hung around to take his punishment, the committee’s recommendation would have been a suspension from the Commons ‘long enough to engage the provisions of the Recall of MPs Act’.

We have had our use out of Johnson just as he has had his use out of us

He spectacularly departed from the Commons on Friday immediately after he saw a confidential draft of the report – denouncing the committee as a ‘kangaroo court’ as he went. This can now be seen as a cunning pre-emptive strike designed to ensure that most of his remaining cult followers keep the faith.

But the committee has not taken this ruse well. It said it views it as containing ‘further contempts’ and says it would have recommended a suspension of 90 days in part because of these further attempts ‘to undermine the parliamentary process’.

Its core finding is that Johnson had ‘personal knowledge’ of lockdown-breaching gatherings in Downing Street. The Committee found he withheld this from the Commons when repeatedly giving false assurances that rules and guidance had been followed at all times.

Those of us who have been prepared to weigh Johnson’s penchant for bluster and slapdashery in the balance alongside his many talents and merits – rather than regarding it as an altogether disabling trait – must now make a forced choice. Either we accept the basic findings of a highly detailed inquiry conducted by a cross-party committee of MPs or we must indulge in a full-on conspiracy theory which takes as its pretext the idea that Johnson and Johnson alone is the true keeper of the Brexit flame. It then follows that ‘the establishment’ has decided to get rid of him in revenge and as the first step in a plot to get the UK back into the EU.

I’m going for the former option and invite fellow Brexiteers to do the same. Do we really want our great cause suborned into a tiny mission to keep alive the political career of a man who rode on its back to a parliamentary majority of 80 and who then went on to egregiously flunk the opportunities thus provided largely because of his own character flaws?

It’s a no from me. To be blunt and perhaps equally as brutal as the Privileges Committee: we have had our use out of Johnson just as he has had his use out of us. It is time to check out of the Boris Johnson Show. He may have opted to try and become the ‘Britain Trump’, but we don’t have to follow him down that path.

Yes, there are some valid questions to be asked regarding potential conflicts of interest or humbug surrounding Harriet Harman and Sir Bernard Jenkin. And yes, a lot of MPs are inclined to believe the worst of Boris Johnson.

But are we to accept that he is too notorious ever to get a fair political trial? Must he therefore be exempted from ‘the network of obligation that binds everyone else’? Are we compelled to back his habit of ‘appearing affronted when criticised for what amounts to a gross failure of responsibility’? Well, hardly. Those last two quotes by the way are drawn from a letter written by his classics master at Eton College to his father some 41 years ago.

When Boris Johnson became prime minister after Theresa May’s ignominious failure, the political context called for someone with chutzpah and flair: a rule-bender who understood that the ends justified the means when it came to ensuring that a core democratic decision was implemented. He was that leader. When Covid descended, the imposition of lockdowns called for someone with almost super-human powers of self-discipline and restraint who could set an example. The late Queen Elizabeth II was that leader and Boris Johnson was very much not.

Paul Simon once sang about a man who didn’t want to ‘end up a cartoon in a cartoon graveyard’. That, alas, is where the giant persona of Johnson appears to be transporting itself. You can call him Boris, but it’s time for most of us to call him Al.

Three things we’ve learned from the Partygate report

The Privileges Committee has today published its findings on whether Boris Johnson deliberately misled MPs over Partygate. The House of Commons voted for such an inquiry, fourteen months ago: its members now have a 100-page, 30,000 word report to trawl through. It makes for damning reading. It finds that Johnson committed multiple contempts of parliament, including deliberately misleading the House, breaching confidence and ‘being complicit in the attempted intimidation of the committee’.

They conclude that ‘there is no precedent for a Prime Minister having been found to have deliberately misled the House’ and therefore recommend a 90-day suspension for him: one of the longest in parliamentary history. An attempt to expel him from the House – a far more serious sanction which would have forced an immediate by-election – was defeated after the four Tories on the seven man panel voted against it. But in an added humiliation, the committee recommend that Johnson lose his former members’ pass: a fate previously suffered by John Bercow.

Below are three things we learned from the mammoth report.

Johnson’s reaction increased his punishment

Boris Johnson pre-emptively quit the Commons on Friday after seeing the committee’s conclusions. But it would be a mistake to dismiss this report as having been overtaken by the events of last week. As the committee make clear, Johnson’s decision to stand down and attack the committee before the report’s publication led to a last-minute update in its conclusions.

‘Mr Johnson’s conduct in making this statement is in itself a very serious contempt’ they find. ‘This was done before the committee had come to its final conclusions, at a time when Mr Johnson knew the committee would not be in a position to respond publicly.’ We don’t know what kind of suspension they were thinking about but the 90-day figure is much higher than the 20-days or so previously being floated in the press.

Johnson’s ‘insincere’ defence of the committee

During his evidence session of 22 March, Boris Johnson praised the ‘distinguished’ members of the committee and that he ‘deprecates’ the use of the term ‘kangaroo court’ with reference to the panel. Johnson subsequently wrote to Sir Charles Walker on 30 March and lavished further praise on the committee. In this letter, published today, he expressed his concern that ‘at the end of what had been a long hearing, I was not emphatic enough in the answers that I provided’ insisting that ‘I have the utmost respect for the integrity of the committee and all its members and the work that it is doing.’

But ten weeks weeks later, when presented with the panel’s report, Johnson broke the confidentiality agreement, quit as an MP and declared ‘Their purpose from the beginning has been to find me guilty, regardless of the facts. This is the very definition of a kangaroo court.’ The committee therefore concluded that ‘this leaves us in no doubt that he was insincere in his attempts to distance himself from the campaign of abuse and intimidation of committee members.’

Like Sue Gray’s inquiry before it, the Privileges Committee probe posed a quandary for Johnson and his supporters. Should they gamely go along with the process and accept its findings graciously? Or should they dismiss it as biased from the start, a stitch-up, a witch-hunt and one without due process? Johnson’s answer was a ‘cakeist’ approach: welcoming favourable developments and rejecting the less favourable. He therefore was willing to go along with the ‘distinguished’ committee – right up until the point when it ruled against him.

Johnson ‘closed his mind to the truth’

The contrast between this report and Johnson’s own 1,679-word response is like night and day: he is defiant, unrepentant and refuses to accept their findings. It’s the same approach he has demonstrated throughout this whole process and the frustration and irritation of MPs at his protestations is clear throughout this report. Johnson told the House that ‘all guidance was followed’ during Covid: the MPs therefore had to examine if this was the case. They looked at six events at which Covid rules were alleged to have been broken; the MPs claim that any ‘reasonable’ person would agree that they were.

Johnson though disagrees. He focuses on things like the assurances given to him by aides, even though, as the committee points out, such assurances refer to one specific event rather than all events. The committee therefore accuses him of making ‘denials and explanations so disingenuous that they were by their very nature deliberate attempts to mislead the Committee and the House’. They say this amounted to effectively having ‘closed his mind to the truth.’

Full text: Boris Johnson’s response to the Privileges Committee’s report

This morning the Privileges Committee published their findings of their investigation into Boris Johnson’s conduct in the wake of the partygate scandal. They found that Johnson had misled the House of Commons and said that, had he not resigned as an MP, they would have recommended a 90-day suspension for him.

As part of their report, the Committee published Johnson’s response to their findings along with their own comments. Here is Johnson’s response in full:

Purported response of Mr Johnson to the Committee’s warning letter, received by the Committee on 12 June 2023, with Committee comments.

- The Committee has provided me with a 36 page document entitled ‘Extract of Provisional Conclusions’ (‘the document’). Despite the fact that they are said to be ‘provisional’, the Committee has declared that I cannot challenge any of its conclusions on the facts, nor comment on any matters in it with which I disagree. In short, the process adopted by the Committee denies me any opportunity to challenge their findings and conclusions, no matter how wrong, selective, unreasonable, illogical or unsupported by evidence. This cannot possibly be fair.

Committee comment: As Mr Johnson and his lawyers well know, the warning letter procedure is an opportunity after the evidence has been considered to respond to the Committee’s provisional conclusions and recommendations. It is not an opportunity to rehearse the evidence that has been received or to rehearse Mr Johnson’s disagreement with that evidence. Mr Johnson has had repeated opportunities to set out his evidence about the facts and has availed himself of those opportunities, in particular in the submissions that he made after all written evidence was available and after he had been questioned in the oral hearing. - To illustrate the invidious and unjust position in which the Committee has placed me, I set out below a critique of just a few of the Committees’ findings. This is merely a handful of the errors and injustices with which the document is riddled.

Committee comment: Mr Johnson had the opportunity to comment on the whole of the document containing provisional conclusions and recommendations but he now chooses only to selectively criticise. To adopt this approach is to undermine the workings of the House because the House is entitled to know what his criticisms are before he discusses them in public, something he implies he is going to do at paragraph 13. - As a preliminary issue, I note that the Committee criticises me for ‘failing to make any use’ of the evidence that I insisted it obtain after my oral evidence session. This criticism illustrates perfectly, as Lord Pannick KC and Jason Pobjoy have pointed out, the unfairness of the Committee being investigator, prosecutor and fact-finder.

My complaint, as the Committee will know from the correspondence, was that the Committee said that it would disregard any evidence that was not accompanied by a statement of truth. This meant that, had my legal team not intervened, the Committee was intending to disregard a great deal of evidence that supported me which, for some reason, it had not chosen to obtain. I had already made use of much of that evidence in my submissions, which I adopted under oath at the oral evidence session, before I understood that the Committee was planning to disregard it. I also made use of some of it in my further submission, although I did not repeat what was in my earlier submissions as they were already before the Committee.

The Committee’s fundamental error is that the responsibility to ‘make any use’ of this evidence was not mine but its own. It is the Committee that must fairly and objectively make use of and have regard to all of the evidence, whether for or against the allegations against me. The document demonstrates that the Committee has failed in this duty. The fact that it lays responsibility for its partial selection of the evidence at my door shows just how profoundly it has fallen into error. Its stance might be justified as a prosecutor in an adversarial process where each party can call its own witnesses before an impartial tribunal. As I had feared, this is precisely how the Committee seems to have approached its task.

Committee comment: Mr Johnson and his lawyers are well aware that the Committee required all evidence to be accompanied by a statement of truth. Contrary to Mr Johnson’s bald assertion, it has considered all of that evidence whether it is supportive of or adverse to Mr Johnson. Mr Johnson had all of the materials available to the Committee and in time to identify any material that he wished to rely upon as evidence and seek statements of truth from those witnesses. He chose to wait until the last moment before the oral hearing to start discussions about the evidence upon which he wanted to rely.

Mr Johnson unfairly complained in that hearing that evidence on which he wished to rely had not been pursued. In any event, he had the right to use all of the disclosed material, whether or not accompanied by a statement of truth, during the oral hearing. He was provided with those materials for that purpose. The Committee asked him to identify the evidence and pursued it for him. Once received with a statement of truth, Mr Johnson chose to place no reliance upon it. There is accordingly no truth in the assertion that the Committee planned to disregard anything that supported Mr Johnson.

My assurances to the House on 8 December 2021

- The Committee accepts that what I actually said about the scope of the assurances I received was accurate: I had repeatedly been assured that the event on 18 December 2020 was within the rules. My words were clear and explicit and had been prepared with input from multiple officials and advisers. I also explained under oath, if there was any possibility of confusion, what I meant by those words.

Despite my words being accurate, clear, undisputed and confirmed under oath, the Committee nevertheless finds that I deliberately gave the House a ‘misleading impression’ that I meant something entirely different. In other words, I am condemned not for what I actually said but for what the Committee has now decided that I meant.

Committee comment: The Committee is entitled to come to a view about the credibility of what Mr Johnson said to the House and to the Committee. In so far as he asserts that there are ‘multiple officials and advisers’ who provided assurances or had input into his statements, Mr Johnson had the opportunity to identify them and did not do so despite indicating that he would. The Committee asked all of the witnesses who it believed had relevant information about Mr Johnson’s knowledge whether they themselves had given assurances to Mr Johnson and none of them other than Mr Doyle and Mr Slack stated that they had personally given such assurances. - Furthermore, the Committee finds that I intended my assurances to be ‘overarching and comprehensive’. Not only is this the opposite of what I said, it ignores completely the fact that, in the very next breath, I announced an independent investigation.

Committee comment: The Committee is entitled to consider what members of the House and the public would have understood Mr Johnson to have said and what he meant by those words. The Committee also concluded that using an announcement about an independent investigation was a deliberate avoidance of his own knowledge. - Finally, the Committee finds that I ‘scaled down’ what I meant by ‘repeatedly’ and that ‘the only assurances that can… be said to have been given with certainty’ were those from Jack Doyle and James Slack.

However, it is the Committee that has scaled down what I said to fit its own conclusion by ignoring the sworn evidence of Sarah Dines MP, Andrew Griffith MP and Jack Doyle, corroborating my own evidence under oath, that I received additional assurances in meetings. There is no explanation for why their evidence is disregarded.

The Committee supports its position by selectively and misleadingly quoting from correspondence. In a letter of 27 March my lawyers wrote:

‘…Mr Johnson thought of an official who was in the morning meetings referred to by Andrew Griffith MP and Sarah Dines MP in their evidence to the Committee. However, he did not say that he knew precisely who was in each meeting and who specifically gave him the assurances remembered by the MPs.

‘On reflection, Mr Johnson is still not sure of these matters and does not wish to speculate. The Committee has evidence from Jack Doyle, Andrew Griffith MP and Sarah Dines MP that Mr Johnson was provided with assurances about the event on 18 December 2020 by officials at these meetings.

‘Therefore, irrespective of the identities of those officials, there can be no dispute that (i) assurances were received from Jack Doyle and James Slack; (ii) three witnesses have given evidence that Mr Johnson received assurances in at least one of the PMQ prep meetings; and (iii) Mr Johnson was given assurances by more than one person and on more than one occasion.’

Committee comment: The Committee has not disregarded the evidence of Sarah Dines MP and Andrew Griffith MP. Their evidence is limited and without the particulars that Mr Johnson failed to provide is insufficient to counter the consistent evidence that no additional assurances were given by anyone. In any event in oral evidence when pressed about whether the Committee should pursue the evidence of Ms Dines and Mr Griffith, Mr Johnson himself said it was ‘probably totally irrelevant’. - In its document, the Committee has quoted only the underlined passage and presented it as if it applied to whether I recalled being given assurances in meetings at all. This is grossly misleading. As the full quote makes clear, I was not sure about who gave me the assurances in the meetings, but that they were given was never in doubt. It assists the Committee in its ‘misleading impression’ argument to find that I only received assurances from two advisers, but that is a complete denial of the evidence.

Committee comment: Mr Johnson’s lawyer’s explanation was considered and is quoted in full in the report. Mr Johnson gave the clear impression in oral evidence that he knew who he wanted to identify and he then failed to identify that person. His explanation for that failure is unconvincing.

My personal knowledge that the rules were broken

- The Committee purports to rule, as a matter of law, that it could never be reasonably necessary for work to attend a gathering purely to raise staff morale, and that the duration for which I attended any event is irrelevant. Therefore, it concludes, I must have known the rules were broken even if I was present at such gatherings only for a few minutes.

This finding is fundamentally wrong in multiple ways. First, the Committee has no power to purport to make such a finding and there is no precedent or judgment in support of its position – it is purely the Committee’s own interpretation of the law. Second, that interpretation appears to be in direct contradiction to the one adopted by the Met Police, who didn’t fine me for my attendance at precisely the same events and who have explained to the Committee that the lawfulness of a gathering ‘may have changed throughout the duration of the gathering’. The Committee does not refer to or have any regard to the Met Police’s advice, which obviously is correct.

Third, as I set out below, it was the understanding of numerous officials who gave evidence to the Committee that they thought they were following the rules. The Committee appears to have devised its legal test just for me.

Committee comment: The Committee does not interpret the law. It is, however, entitled to compare the plain language of the Rules and Guidance with what Mr Johnson said at the time when he was exhorting the public to follow those Rules and Guidance, and Mr Johnson’s attempts in evidence to re-interpret what the words meant. - Finally, the Committee’s reasoning ignores the actual question it must answer, which is whether I honestly believed that the rules had been broken at the events I attended. The Committee can only find otherwise by unilaterally declaring my attendance as unlawful and then asserting that, uniquely amongst everyone at No. 10, I must have known that to be the case.

Committee comment: The Committee is entitled to conclude on all the evidence that Mr Johnson did not honestly believe what he said he believed or that he deliberately closed his mind to the obvious or to his own knowledge.

My personal knowledge of the event on 18 December 2020

- The Committee’s findings about the event on 18 December 2020 appear to abandon completely any adherence to the ‘clear and cogent evidence’ test which it accepts it must adopt, and enters the realm of pure speculation.

I gave evidence on oath that I was not aware of any event taking place and I did not recall seeing anything that appeared to me to be against the rules when I went up to my flat at 21.58 that evening. Even if, despite my evidence to the contrary, the Committee found that I must have glanced up, there is no evidence whatsoever before the Committee about what was happening in the press office at that precise moment. There is, however, plenty of evidence before the Committee that the number of people present varied throughout the evening, that people came and went, and that many stayed at their desks to work.

Despite this evidence, the Committee finds, based on its own site visit, that (i) I looked into the vestibule; and (ii) I saw a gathering in breach of the rules. In support of this finding, the Committee refers to the facts that ‘drinking began at 5pm’ and ‘continued till “the early hours”’ and that the event was not work-related for ‘at least some of the time’.

It is not explained how evidence of what was happening at completely different times has any bearing on what I would have seen had I glanced across at 21.58. Moreover, if the event was work-related for ‘some of the time’ then there is no basis whatsoever for finding that I must have seen a rule-breaking gathering at that precise moment, let alone that I would have recognised it as such.

Committee comment: Mr Johnson ignores the plethora of evidence about how obvious it would have been to him at 9.58pm that something was happening that was in breach of the rules and guidance. The Committee concluded that it is likely that he knew about this particular gathering.

The argument from silence

- The Committee fails completely to answer the point that, if it should have been obvious to me that these events were contrary to the Rules and guidance, then it should have been obvious to many others too. The Committee has not pointed to any evidence that anyone felt inhibited or scared to raise concerns either with me or with their superiors – this is pure speculation.

The evidence cited in support of the Committee’s finding – that one official said they were ‘following a workplace culture… I did it because senior people did it’ is evidence that they and the senior people referred to thought, as I did, that they were following the rules. It contradicts rather than supports the Committee’s findings.

More importantly, the Committee has not quoted from or even summarised the numerous witnesses who gave sworn evidence that they thought they were following the rules. Again, the evidence that supports me and contradicts the Committee’s findings is simply ignored.

Committee comment: Mr Johnson was alerted to the possibility of breaches of the guidance by his Principal Private Secretary, Martin Reynolds. It is not correct that there is no evidence that it was obvious to others. Mr Johnson has that evidence from a senior No. 10 official as well as the evidence of Lee Cain and Jack Doyle’s WhatsApp message. The interpretation of the guidance

The interpretation of the guidance

- The Committee now accepts that I am correct that the guidance required social distancing ‘wherever possible’ and that the instruction that ‘only absolutely necessary participants should physically attend meetings’ was one that ‘usually’ rather than always applied.

However, despite my reading of the guidance being correct, and the Committee having to accept that its own reading was wrong, the Committee somehow concludes that my interpretation was a ‘contrivance to mislead the House’. Again, the Committee appears to have come up with a standard that applies only to me.

Committee comment: The Committee did not erroneously interpret the rules and guidance. It considered Mr Johnson’s interpretations and considered that they were false. - These are just a few examples of why I reject the findings in the document. In due course, I hope to have the opportunity to set out my objections to the Committee’s findings in full without demonstrably unfair restrictions placed upon my right to challenge them.

Committee comment: If Mr Johnson had submissions about the provisional conclusions and recommendations he should have made them to this Committee and to the House not reserved them for some future discussion of an unspecified nature.

The partygate report is damning for Boris Johnson

The Privileges Committee has published its report on whether Boris Johnson deliberately misled parliament over partygate. It is damning.

The 30,000-word document finds that he committed multiple contempts of parliament, including deliberately misleading the house, deliberately misleading the committee, breaching confidence, impugning the committee and the democratic process of the house and ‘being complicit in the campaign of abuse and attempted intimidation of the committee’.

The committee, consisting of seven MPs including four Tories, had to update its conclusions after Johnson resigned, saying that it would have recommended a 90-day suspension of the former prime minister. But it has now recommended that he should not be granted a former members’ pass. This punishment seems to have increased as a result of the response from Johnson to the inquiry and its conclusions: it is not just about the initial offences where he told MPs that he had been assured that the guidance had been followed at all times.

The key section in the report concerns Johnson’s attitude to the inquiry itself

When it comes to that initial incident of misleading the House, the committee rests heavily on the evidence from his former press secretary Jack Doyle and private secretary Martin Reynolds. The report concludes that this evidence shows that Johnson did not receive the level of assurance that rules and guidance had been followed at all times. It points out that:

‘Doyle has stated that he did not discuss whether any gatherings had been compliant with Covid guidance, as opposed to Covid rules, and did not advise Mr Johnson to say No. 10 had complied with Covid guidance at all times.’

Reynolds also told the Committee that he had ‘questioned whether it was realistic to argue that all guidance had been followed at all times, given the nature of the working environment in No. 10’ and that ‘he agreed to delete the reference to guidance’.

But the Committee then says that, despite this, ‘we note that Johnson subsequently on at least three occasions asserted in broad terms that guidance had been followed’. It then says that his evidence to the committee say Johnson ‘downplay the significance and narrow the scope of the assertions he made to the House’, which was directly at odds with the overall impression Members of the House, the media and the public received at the time from Mr Johnson’s responses at PMQs’.

But the key section in the report concerns Johnson’s attitude to the inquiry itself, saying that he had ‘sought to re-write the meaning of the rules and guidance to fit his own evidence’. The Committee says it ‘came to the view that some of Mr Johnson’s denials and explanations were so disingenuous that they were by their very nature deliberate attempts to mislead the Committee and the House, while others demonstrated deliberation because of the frequency with which he closed his mind to the truth’. He is also accused of breaching confidentiality by making a public statement about the report last week which was ‘in itself a very serious contempt’.

There was an attempt last night by Labour MP Yvonne Fovargue and SNP Allan Dorans to change the recommended 90-day suspension to a full expulsion from the House, but the Committee was divided on this and it was voted down 4-2.

Johnson has described the report as ‘deranged’ and a ‘lie’, claiming it is a ‘dreadful day for democracy. He and his allies have been very keen to paint the Committee as being biased against him from the outset. He has also wanted to portray the Tory majority among its members as being illusory because those Tories are, in one way or another, anti-him.

The implication of this is that the House of Commons shouldn’t govern itself and MPs shouldn’t be expected to act with integrity when sitting on these committees. It is curious that Johnson has only started making this case for what would be a major piece of reform of the way Westminster works when he is the one under judgement. Because the Committee has escalated its sanctions in response to his attitude in recent days, and because Johnson himself is escalating his own language in response to the report, this row is turning into a cyclone which threatens to damage everything in its path. Johnson may never return to parliament – or he might – but the consequences of the inquiry and the way he has attacked it will last for a very long time.

Putin is lining up a lengthy list of scapegoats for his war

Lately Vladimir Putin has been strikingly unwilling to subject himself to any serious debate about his war in Ukraine. On Tuesday, he came the closest yet, spending more than two hours talking to war correspondents working for either the state media or nationalist social media channels. It was hardly an inquisition, but there were some interesting insights into his thinking to be gleaned.

Despite the clear evidence of a steady contraction in the Kremlin’s aspirations and expectations from the original intent to conquer the whole of Ukraine, he refused to accept that the goals of the ‘special military operation’ had changed in any way. Rather, he asserted, that although they may alter the detail ‘in accordance with the current situation, but in general, of course, we will not change anything, and they are of a fundamental nature for us’.

While claiming confidence, Putin seems to be lining up a list of potential scapegoats in case things go wrong

In many ways this was a direct rebuttal of recent suggestions that some kind of peace deal and thus compromises might be necessary. He claimed to respect Ukrainian sovereignty, but that this had been abused in the name of aggression: ‘as for someone who wants to feel Ukrainian in Ukraine and live in an independent state, for God’s sake, do what you want. We must respect this. But then don’t threaten us.’

Instead, front and centre, the United States become the villains of the peace. They were the ones, Putin said, driving Ukraine to war. Indeed, the Americans are also forcing Europe to back Ukraine (something that might surprise more hawkish allies such as Poland that have been trying to push Washington into more extensive support). After all, ‘they don’t care about the interests of their allies. They have no allies, they only have vassals. And the vassals have begun to understand what role they were destined for’.

This is actually a subtle shift in emphasis. First, the war was against Ukraine, then Ukraine as a proxy and ally of the West, now Ukraine almost as a victim of the United States. What follows, though, is that any peace would be achieved by direct talks with the Americans: ‘If they really want to end today’s conflict with the help of negotiations, they only need to make one decision: to stop the supply of weapons and equipment – that’s it.’

Of course, this is a serious misreading of the complex dynamics of this war. Not least as without Western military support the Ukrainians would have a great deal more trouble defending their country, but at present every opinion poll suggests a determination to do so regardless. However, it reflects Putin’s worldview, in which a handful of great powers dictate the future of the rest. It also hints at how he thinks this war can eventually be settled, through a gentleman’s agreement between Moscow and Washington, that would inevitably bolster his increasingly threadbare claims to Russia’s great power status.

One could, of course, wonder why he thinks such a deal is needed, given his efforts to present the Ukrainian counter-offensive: as a failure: ‘The enemy did not succeed in any sector. They have suffered serious losses… we are suffering ten times fewer casualties than the armed forces of Ukraine… According to my calculations, [Ukraine has lost] about 25, or maybe 30 per cent of the equipment delivered from abroad.’

In that context, no wonder he said that there was no need for another wave of mobilisations, because casualties are low and, according to Putin, 156,000 Russians had volunteered to fight. ‘Under these circumstances,’ he added, ‘the Ministry of Defense reports that, of course, there is no need for mobilisation today.’

That closing comment, placing the responsibility on the Ministry of Defence (that, according to some reports, has actually been advocating a mobilisation this summer) reflects a leitmotif of Putin’s statements since the start of the counter-offensive that belie his bullish claims of victory. When asked about the threat of drone strikes inside Russia he said ‘it would be better if this was done in a timely manner and at the proper level… I am sure that these tasks will be solved.’

As for Ukrainian sabotage operations, the law enforcement agencies needed to up their game. Meanwhile, he was sure the Ministry of Defence was looking to replace time-serving ‘parquet generals’ with new blood that had shown its mettle in battle, but that ‘the bureaucracy there is the same as in any Ministry’.

In short, the commander-in-chief, the man with direct authority over the police and security agencies alike, was disclaiming any real power to address any of these agencies’ failures. He was simply ‘hoping’ that what was needed was being done. Once again, while claiming confidence, Putin seems to be lining up a lengthy list of potential scapegoats in case things go wrong.

One, indeed, might already have been identified. As part of his running feud with Yevgeny Prigozhin and his Wagner mercenary group, Defence Minister Shoigu has demanded that all such volunteers sign contracts directly with his ministry. Prigozhin has angrily refused, but Putin for once backed his minister, saying it needed to be done.

Of course, Putin has made declarations before without actually following through. Given also that this press conference was held with a very select group of commentators who would reliably treat his words with respect, it is unlikely to win over those critics who believe he is proving unable to match words with deeds. None of the bloggers associated with Prigozhin were invited, for example, nor the ‘turbo-patriot’ Igor Girkin. He acerbicly concluded that Putin’s overall strategy had become clear: ‘If there is the slightest opportunity to do nothing, we will definitely take advantage of this opportunity!’

Why I hate the new Pride flag

If you needed more proof that gay men aren’t in control of things any more – at least where the activist set is concerned – look no further than the evolution of the LGBTQ+ Pride flag. If, as Oscar Wilde once wrote, ‘Fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to alter it every six months’, then the new Pride flag is somewhere between a prisoner of war and Frankenstein’s monster: a tortured and overburdened horror; a stitched-together crime against nature.

What was wrong with the old rainbow flag? Rainbows are happy and beautiful. Everyone loves a rainbow. And that, precisely, was the problem. You can’t strike fear into the hearts of your enemies with a rainbow. Big Gay needed something more militant.

The first edit came a few years ago, with the addition of brown and black stripes, which don’t belong on a rainbow but do belong in intersectional grievance hustling. Then, in from the left side, like a tunnel-boring machine spectacularly grinding away all that harmony, appeared the Triangle of Trans. This new version is what you’re likely to see today gently flapping outside your kombucha bar or pottery studio during the month of June.

But the queers weren’t finished desecrating the rainbow. The latest iteration allows any sexual identity group in the world to join in by finding a bit of empty space on the design in which to slap their logo. The once joyful and balanced rainbow flag now looks like the dilapidated, bumper-sticker-loaded car of a hoary college professor.

Let’s be honest, the original rainbow Pride flag was always a little gay, and by that I mean lame. Rainbows are majestic, breathtaking, awe-inspiring when sent from heaven. But a grown man wearing one on a T-shirt looks a bit pathetic, if you know what I mean.

After all, rainbow apparel is for children. How is it that rainbows – symbols of innocence, wonder and purity – became synonymous with the most debauched and cynical of subcultures? Grown men donning rainbows was perhaps a warning sign that this really is a community of Peter Pans. And I speak as one of them.

What’s worse: all this flag-waving has robbed children of the rainbow (not to mention Christians where, in the Bible, it is a symbol of God’s loving covenant to all generations after the great flood). Nowadays, you can’t even dress your toddler in an innocent rainbow jumper without someone giving you the stink-eye as they wonder if you’re trotting off with Junior to the gender reassignment clinic.

The same goes for the brave gay man who brandishes that outmoded six-stripe rainbow banner of yore. Is he a transphobe, neighbours might wonder. The world is engulfed in madness. Let’s hope, like the rainbow itself, this too proves ephemeral.

What do we think of when we think of Essex?

Apparently much of the notoriety – or perhaps by now it has become allure – of Essex is my fault. In 1990, weeks before Mrs Thatcher was defenestrated, I wrote an article in the Sunday Telegraph called ‘Essex Man’, in circumstances that Tim Burrows describes entirely accurately in this exceptionally well-written and intelligent book. Although the Iron Lady was about to be history, the part of England that had come to exemplify her achievement and her legacy was throbbing with capitalist energy more than ever – which motivated the profile of Essex Man and his hard work and ability to seize opportunities in a society where native ability counted for more than class. From that came The Only Way Is Essex, jokes about Essex Girl (thanks not least to the great Richard Littlejohn, who differentiated her from a shopping trolley by asserting that the latter had a mind of its own), and the notion that, with black people and the Irish no longer available as targets of humour, Essex would fill the gap.

Burrows is an Essex native who moved back to Southend to avoid the absurdities of the London property market. He has an implicit understanding of the temper of the great diaspora of cockneys who moved out to the south of the county after the war, though some had already left East and West Ham after they became industrialised at the end of the 19th century. He also understands the pull of the quiet emptiness of the marshlands that surround the coast, and of the islands and creeks in the estuaries of the Thames, the Crouch, the Blackwater and the Colne.

Essex has a vast acreage of picture-postcard villages, a few of them near the marshes on the Dengie peninsula and in the largely unknown corner of the county north of Southend, but most of them north of Chelmsford, populated in part by what in Essex passes for old money. That substantial area of the county is one with which Burrows does not appear unduly concerned. His fascination is for the new towns of Harlow and Basildon and the social experiment they represent; and for the inhabitants of the housing estates that have sprung up over the past 50 years in this constantly expanding county, around its old towns and villages.

Essex was, in the last century, sliced in two by the expansion of London. There was that substantial part along the north shore of the Thames that was colonised by Londoners, and whose boundaries crept northwards over the decades: the move out began after the Great War, with the so-called ‘plotlands’ around what is now Basildon and along the River Crouch, where aspirational East Enders bought their slab of land and, in an age before planning permission, invaded the countryside with their bungalows. Contrasted with this is what Burrows correctly calls the ‘bucolic’ part, north of the county town of Chelmsford, increasingly colonised by the successful middle classes, inhabiting what until the 1950s and 1960s were working farmhouses or tumbledown cottages. The first part is lodged in the home counties, even if it doesn’t conform to the clichéd salubriousness associated with Surrey or the Middlesex and Hertfordshire metroland. The second is essentially East Anglia. In some counties this cultural clash might cause a sense of schizophrenia: in Essex, the two worlds live cheek by jowl, and just get on with it.

Picture-postcard Essex, as Burrows points out, was at the start of the last century in serious decay, during the great agricultural depression that lasted from the early 1870s until the first world war, just as the industrialised parts of the county were causing urban Essex to expand. Much of that part of the county has, since 1965, been in Greater London, but Ilford and Romford and Barking and Dagenham (the last with one of the largest council estates ever built) still have Essex postal addresses. And the coast, too, has witnessed much expansion. Canvey Island, swamped by the great flood of January 1953, is now home to 40,000 people: and further north, on the outskirts of the resort of Clacton – home to Butlin’s second holiday camp and now in a state of obsolescence – is Jaywick, a settlement of bungaloid growth, designated a decade ago the most deprived place in England.

This is a thoughtful, atmospheric book of genuine insight and erudition. I have lived in Essex most of my life, but I nevertheless learned things from it, partly because it deals so thoroughly with the part of the county I know least. Essex really is special, because of its refusal to indulge in conformity, and Burrows’s book conveys the reality of the place in a way that amplifies its uniqueness. If you are interested in this remarkable microcosm of England, the book will grip you; if you aren’t, it will make you realise that you jolly well should be.

The beauty of rosé and roses

What an idyllic setting. We were amidst the joys of high summer in England, with just enough of a breeze to save us from the heat of the sun, and the further help of a swimming pool. Water without, wine within. We were also surrounded by roses, England’s flower, luxuriating in their beauty and innocence. Experts have applauded my friends’ rose-husbandry. It seemed to this non-expert that they have not merely created a good rose garden; they have triumphed with a great one. Yet other thoughts intruded.

Godparents are supposed to abjure the devil. Might Satan not sue for breach of contract?

Roses makes one think of Henry VIII. I have recently been reading C.J. Sansom: so much better than Hilary Mantel. His Henry is wholly convincing as a study of corruption and evil. That monster-monarch’s emblems were frequently adorned with roses. It seems to have been his favourite flower: the Tudor rose, beloved by England’s cruellest King, the murderer of Queens and many other victims.

While we were drinking to my friends’ roses, I was drawn on from Henry VIII to the White Rose, that association of Bavarian students in the 1940s who included Sophie Scholl: more innocence, more beauty. A child of an older, gentler Germany, she was determined to bear witness that not all Germans were besotted by evil. But in the short run, she and her friends did not stand a chance. It was inevitable that their white roses should be crushed by the tank tracks, the death camps. Yet one could almost say they died in order that their country might live. The inspiration of their martyrdom was part of the moral rebirth of post-war Germany.

These thoughts, though, were untimely. In such a weekend of wine and roses, it was easy to leave the sins of the world to the Agnus Dei. Apropos roses, we drank a fair amount of cooling rosé, but a magnificent sea trout was complemented by a 2014 Meursault from Pierre Bourée. That year, which was initially underrated, because it was overshadowed by the power of the 2015s, has come into its own. But the victor ludorum, as so often, was Léoville Barton. I refuse to apologise for reverting yet again to that great vineyard’s glories. Those who know it well will not mind. It will merely arouse thirst. Those who have yet to encounter it have a pleasure in store. We enjoyed the 2001: a perfect drop of claret and an ideal accompaniment to delicious carpaccio.

One of our number was still not quite old enough for claret, but young Arthur had earned his lunch. He had spent two hours in Sherborne Abbey, singing, inter alia, an Agnus Dei. That abbey is another enclave in a darkling world: the Church of England as it ought to be. Endowed by the beauty of the ages, by the proper English liturgy and by the prayers of the faithful – almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian.

A numismatist as well as a chorister and an aspirant gardener, Arthur had been particularly taken, during the coronation service, by ‘Zadok the Priest’. Good music enters the bloodstream, and thus it was with him and Zadok. The grown-ups were happy to encourage him to go on singing it.

Oddly enough, I had not featured in Boris’s honours list. Yet compensation awaited. I was honoured when asked to become a late-onset godparent and promised not to bring too much disgrace on this splendid godson. Vivat Arthur. I had only one source of anxiety. In the C of E, godparents are supposed to abjure the devil and all his works. Might Satan not sue for breach of contract? But I cannot see Mephistopheles lurking about in Dorset. This is sacred ground.

The high and lows of a Hong Kong jockey

You can take a jockey who has ridden there out of Hong Kong; it’s a lot harder, I reflected, after a chat at Newbury with Neil Callan, taking Hong Kong out of the jockey. Even though this is his second season back on home territory after spending ten years in that racing pressure cooker, Neil still watches every one of the 18 races a week at Sha Tin and Happy Valley and remains grateful for what Hong Kong did for him. He went out there as a good jockey – you don’t get invited to take up a Hong Kong contract unless you are in the top echelons elsewhere – and he came back a better one.

Back in the UK, Neil Callan, the champion apprentice in 1999, had been in the top five for some years. In 2005 and 2007 (when he rode 170 winners) he was runner-up in the jockeys’ championship although, ever the realist, he adds that Jamie Spencer and Seb Sanders led him by a solid margin. When he first went to Hong Kong on a short-term trial he found it hard, taking six weeks to ride his first winner. After his first full season he was in two minds, but then, while taking a week’s holiday in Thailand on the way back to Britain, he received a call. With injuries and suspensions they were short of jockeys for the next fixture. Would he come back for one more weekend? He did so, bashed the phone to trainers seeking spare rides and collected nine in ten races. Two were winners, four came second and only one finished out of the first four. He phoned his wife Trish to say, ‘I’m coming back’, and the family moved to the former colony in 2014.

For a jockey the lifestyle is altogether different: there are only two meetings a week and you don’t spend hours on the road between the 35 Flat racing tracks in the UK staging racing every day of the week or pleasing trainers across the land by turning up to ride work. In Hong Kong Neil would be at the training track from 4.45 a.m. to 8.30 a.m., partnering the seven or eight ready tacked-up horses he was likely to be riding at Happy Valley on Wednesdays or Sha Tin at the weekend. Jockeys there get 10 per cent of winning purses, which are hugely generous by UK standards, and 5 per cent for placing second to fifth.

But the pressure in front of heavy-betting and vociferous crowds averaging more than 40,000 is intense. ‘In Hong Kong there’s no hiding place,’ he says. ‘With only 18 races a week to prove yourself, you have to be so mentally sharp.’ In Britain, he argues, most races develop only over the last half-mile. ‘In Hong Kong it’s all about speed from the gate and position through the race. You need your brain switched on all the time: it’s about reaction speed, positioning and balance.’

Clearly it is also about determination: in Hong Kong, where he won top races such as the QEII Cup on the appropriately named Blazing Speed and the Classic Mile on Beauty Only, they gave him the nickname ‘The Iron Man’. The lighter racing programme also gave him time to improve his diet and fitness: ‘I am mentally and physically better prepared. I really upped my game.’ In his gentle Irish accent a note of scorn creeps in only when he talks of those who are not prepared to put their heads down and graft for opportunities.

That is what he has had to do on coming back to Britain after those well-rewarded ten years. He and Trish returned because they have four boys, two of an age to be tempted by the pony-racing circuit that is now so vital for would-be young jockeys. It was family payback time. Not everybody with rides to offer was immediately recalling 44-year-old Neil’s past successes such as Borderlescott’s Nunthorpe Stakes or the two-year-old exploits of Amadeus Wolf for his old chum Kevin Ryan. ‘There was a whole different array of new trainers. I was under no illusions and nothing comes without hard work but I am in a good space.’ That is a fair assessment.

Thanks to the Hong Kong sharpness, he has done far more than pick up the threads of a past career: the day we met at Newbury Neil Callan was back in the top five jockeys list with a strike rate of 20 per cent winners to rides. That day he had rides for Dominic Ffrench Davis, Charlie Fellowes, Marco Botti (with whom he has forged an effective alliance), Charlie Johnston, Ed Dunlop and Michael Bell. After we spoke, there were two races left on the card: Neil took the 1½-mile Class 4 Handicap on the top-weight Seal of Solomon for Ed Dunlop at 6-1, dictating a shrewd pace on a horse who had won over two miles. He then followed up with an all-the-way victory on Michael Bell’s Burdett Road over ten furlongs at the same price. A pretty decent day’s work.

My pilgrimage to Lourdes

‘Will someone steal my coat?’

‘No, you’re on a holy pilgrimage,’ my son’s Irish carer-companion Rosemarie reassured him. We were going to Lourdes, where in 1858 a poor peasant girl, Bernadette Soubirous, had 18 visions of the Virgin Mary.

At Stansted I’d lost a tooth. I had a bad knee and an ancient foot injury. Should I not be in a wheelchair myself, instead of being a helper? Our group was BASMOM, the British Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. I was a bit dubious about Lourdes (Rosemarie’s idea). Wasn’t the Order full of recusant Catholics who my father, a Knight of Malta himself, always claimed were ‘interbred’? He’d cited loo rolls playing Ave Maria (probably a myth), and as a Catholic child I was familiar with lurid statuettes of Bernadette and the Virgin and ‘bling’ rosaries.

I would be in a hotel with other helpers, Companions, Knights and Dames. We would work in teams at the Accueil, where our guest pilgrims (formerly called ‘malades’) resided. My son Nicholas (39, Asperger’s) and Rosemarie would stay there. My old schoolfriend from the Sacred Heart, high-powered Anna, and her brother, in a wheelchair, go annually.

Due to our plane’s lateness, my team was sent straight to the Accueil, to help guests unpack. It was a baptism of fire. Terrified, I overheard the word ‘hoist’. I was not nurse material. A helper I’d identified as a ‘Holy Mary’ started heaving guests’ suitcases. I did not participate, due to a dodgy back. I finally got to my tiny hotel room well after midnight. I had to phone for a towel.

Due back at the Accueil at 7.30 a.m., I was so anxious I hardly slept. My new nurse’s uniform was impossible to put on and I had to ask an Italian Dame of Malta in the hotel lift to tie my apron.

We were told to knock on guests’ doors and offer help. Some women, half-dressed, looked discomfited but I did assist a tall lady with a lovely face, on crutches, by carrying her teacup. Luckily an experienced helper known as Mad Jane came to the rescue and she and I served breakfasts. This was fun, as I met pleasant chatty women who’d had interesting jobs. One recognised my surname as that of a racing motorist killed on Lake Windermere, where she’d spent her childhood. I befriended Swiss Ursula, the only Protestant, whose husband had died of Covid. Despite her liveliness, she was in permanent pain due to a botched spinal injection long ago.

That evening a Catholic widower, a retired psychiatric nurse, escorted me, Rosemarie and Nicholas to the grim former home of Bernadette’s family. Nicholas was awed and Rosemarie talked of Bernadette’s often sad life. She had not always been believed and a fence had been erected across the grotto where she had seen the Virgin. At one sighting the Virgin had announced: ‘I am the Immaculate Conception.’

Does it matter if one is not a complete believer? I have always found the idea of Jesus being born without his parents having sex hard to swallow. However, after three days my foot injury disappeared, seemingly for ever. My son was happy. I loved hearing snatches of the French Mass at the Grotto across the river and ‘Salve Regina’ sung in Latin reminded me of evenings at school, where I’d made friends for life. I was impressed by the fortitude of our pilgrim guests: the gallant musical boy with MS from a northern town; the young woman with a Stephen Hawking-type voice synthesiser; and Anna’s brother, a calm, comforting presence despite his lifelong impairment.

There were funny moments. In our procession to the Grotto in heavy rain, Ursula got soaked and refused to leave the Grotto’s shelter, saying it was ‘un-Christian’ to force her out. The ‘Holy Mary’ became very bossy over my tap cleaning and, refilling my bucket, I felt obliged to ask her husband if she’d been head girl of her convent.

A lovely retired teacher’s bag disappeared, so my son’s initial fear was realised. ‘Forget Jesus, ring your bank!’ Ursula advised. A young ebullient priest sang ‘La Vie en Rose’ on our bus to Bernadette’s aunt’s village, Bartrès, where there was a Mass for Anointing the Sick. I didn’t think I was eligible but Rosemarie made sure my son got anointed.

On a serious note, BASMOM, besides helping the poor and the sick, is involved in organisations such as the Nehemiah project in south London for ex-prisoners.

An old Lourdes hand said that if newcomers don’t ‘run for the hills’ after two days, they usually return. I think I will. My son wants to. Meanwhile, an 18-year-old crocodile has given birth with no male input. So perhaps Mary did not use Joseph for that purpose after all.

Why hasn’t Nadine Dorries resigned yet?

Nadine Dorries has this evening explained why she isn’t yet resigning as an MP, after she initially quit ‘with immediate effect’ last Friday. The Mid Bedfordshire MP had gone mysteriously quiet after her announcement, prompting Downing Street to suggest that she was letting her soon-to-be-former constituents down. She has now revealed that she is waiting for a subject access request to the House of Lords Appointment Committee, Cabinet Secretary and Cabinet Office.

I understand from friends of Dorries that she is ‘desperate to resign’ and is upset about having to remain in place while she waits for the subject access request to be returned, but that a lawyer in her constituency approached her and advised her that she may need access to parliamentary privilege with the results of that investigation. She has requested all WhatsApp and text messages, minute of meetings and emails relating to her possible inclusion on the nominations list for a peerage, after conflicting accounts emerged of who blocked it and who was told what and when.

My personal hunch is that this stand-off with Nadine Dorries could have been avoided

There is talk of a campaign from Boris Johnson and his supporters to get at Rishi Sunak. But my personal hunch is that this stand-off with Nadine Dorries could have been avoided had there been a quiet word with her at an earlier stage about a future peerage, or why she wasn’t getting one. Instead, she has been, in the view of a number of MP colleagues, a ‘humiliation’ and a ‘public dismissal’ of her that was guaranteed to upset her and lead to this kind of fight. Neither side is backing down now, meaning the Tory psychodrama has several more acts to run.

Did an MP on the Privileges Committee break lockdown rules?

The Privileges Committee are all set to deliver their report into whether Boris Johnson lied to parliament – but there’s a sudden, last-minute twist in the tale. Guido Fawkes – that enduring sore on the national body politic – has revealed tonight that Bernard Jenkin, a member of the panel, attended a lockdown-breaking bash for his wife during the pandemic. It’s prompted Johnson to demand his resignation from the committee, hours before it’s set to deliver a judgement on him.

Sir Bernard has denied attending ‘any drinks parties during lockdown’ – including an event hosted by Deputy Speaker Eleanor Laing in December 2020. Yet now Nadine Dorries (who else?) has written to the committee clerk, prompting an investigation by Chair Harriet Harman. Dame Eleanor told Guido that she held a ‘business meeting’ on that evening, where ‘I was so strict with my 2 metre ruler and told everyone we will adhere to those rules and be very careful.’ Are such assurances more plausible than Johnson’s talk of ‘essential’ No. 10 work parties?

Boris Johnson has now gone public and released the following statement:

If this is true, it is outrageous and a total contempt of Parliament. Bernard Jenkin has just voted to expel me from Parliament for allegedly trying to conceal from Parliament my knowledge of illicit events. In reality, of course, I did no such thing. Now it turns out he may have for the whole time known that he himself attended an event – and concealed this from the privileges committee and the whole House for the last year. To borrow the language of the committee, if this is the case, he ‘must have known’ he was in breach of the rules. Why didn’t he say so?

Jenkin, admittedly, hasn’t lied to the House – but it’s not the best look for a committee member passing judgement on colleagues…

Support Sturgeon or quit, says Humza

Just when they thought they were out of the woods, the SNP have been pulled right back in. Following Nicola Sturgeon’s sensational arrest on Sunday, reports have emerged that First Minister Humza Yousaf is willing to exhaust all options in a bid to get his party under control — and has gone so far as to tell his MSPs to back Sturgeon or quit the party. No Privileges Committee investigation for her to worry about…

There’s only so many times a First Minister can be called ‘weak’ before he snaps. Three separate sources have told the Times that, at a private meeting in Holyrood, Yousaf issued veiled threats to his politicians, primly reminding them that they were expected to publicly support his decision to allow Sturgeon to retain the whip. If they didn’t, Yousaf warned, they’d be doing damage to the independence cause. Ah, the classic separatist threat never gets old…

Humza’s allies (both of them) have presented a slightly rosier view of events. Mr S hears that he spent the meeting begging his politicians to band together in the name of party unity. ‘I did not read the riot act,’ Yousaf assured inquisitive journalists. And despite a number of SNP politicians calling for Sturgeon’s suspension, the show of goodwill went on — culminating in a present of flowers in ‘sympathy’ for dear Ms Sturgeon. Let’s hope they weren’t funeral lilies.

It’ll take more than flowers and a sharp tongue to whip these politicians into line, though. A fair few politicians are bitter about Yousaf’s refusal to suspend his predecessor and not all of them are keeping quiet about it. Coming soon to an anonymous briefing near you…

Rishi’s PMQs victory counts for nothing

Honours dominated the exchanges at PMQs. Sir Keir asked why the Tories have spent an entire week bickering about which Conservative deserves ennoblement. Rishi claimed that he followed ‘established convention’ in approving Boris’s lavender-list. A bit of a whopper. He clearly didn’t support the candidacy of Nadine Dorries who complained in frothing prose about the ‘sinister forces’ that denied her a peerage. Sir Keir failed to spot Rishi’s clumsy footwork and instead he pretended that the PM approved ‘Johnson’s list’ in full.

‘Too weak to block it,’ said Sir Keir.

Rishi shifted tack and mentioned the peerage granted to Labour’s Tom Watson who, he said, ‘spread vicious conspiracy theories that were utterly untrue and damaged our public discourse’. This earned a knuckle-wrap from the Speaker who said it was wrong to speak the truth about Lord Watson.

Sir Keir set out today to smear Rishi as a slippery weakling, but the caricature fails because it’s not rooted in existing perceptions. Rishi is tough, astute, fast on his feet and formidably well-prepared for PMQs. And Sir Keir’s inability to skewer his opponent compels him to use generic insults like ‘Tory cronies’ or to yell out knackered old slogans – ‘they should hang their heads in shame.’ Sir Keir can’t win against Rishi but he doesn’t need to. The sea is running in Labour’s direction. For a full half-hour today, the party’s frolicsome backbenchers cackled and gibbered like a crew of coke addicts anticipating the arrival of their dealer.

Labour’s frolicsome backbenchers cackled and gibbered like a crew of coke addicts anticipating the arrival of their dealer

Rishi drew attention to Labour’s gravest recent blunder: its pledge to withhold new North Sea drilling licences. Jubilation will break out in the Kremlin, warned Rishi, as Putin celebrates a policy that will deliver ‘British jobs for Russian workers’. The PM estimates that 200,000 UK employees might be thrown out of work by Sir Keir’s eco-insanity. Excellent point. If Rishi had any sense he’d call an emergency summit with the oil majors to discuss the risks of a Labour government. Then again, if the oil majors had any sense they’d decline the invitation. The withdrawal of new licences will give Big Oil a boost. Prices in the UK will rise and extra diesel will burn as tankers chug around the world bringing foreign oil to these oil-rich shores.

Stephen Flynn of the SNP, looking as cuddly as a cactus, unearthed a quote from last summer made by Rishi about the policies of Liz Truss which might cause mortgage repayments to rise. Millions would be ‘tipped into misery’, Rishi said about a year ago. ‘And we’ll have absolutely no chance of winning the general election.’ Flynn asked the PM: ‘Does he still agree with his own electoral analysis?’