-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Why did Truman Capote betray his ‘swans’ so cruelly?

The first rule in John Updike’s code of book reviewing is: try to understand what the author wished to do and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt. I should therefore not blame Laurence Leamer for failing to capture in Capote’s Women any sense of what made Truman Capote irresistibly attractive to all sorts of people – rich, poor, male, female and especially to his flock of high-society swans, the women of Leamer’s title. Nor should I blame him for failing to identify what made Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood both beloved by critics and hugely popular. I can’t blame Leamer, because what he has attempted is a book of undiluted gossip, and that’s what he has achieved. ‘Submit,’ Updike urges us, ‘to whatever spell, weak or strong, is being cast.’ I submitted – and felt like I was caked in slime.

Capote was warned that spilling his swans’ secrets would be a disaster

There is a plot of sorts. Capote made his name against the odds, thanks to hard work, charm, compulsive self-promotion, social climbing and true literary genius. All his swans – Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness, Slim Keith, Pamela Harriman, C.Z. Guest, Lee Radziwill, Marella Agnelli – were blessed with great beauty, grace, style and varying degrees of intelligence. Most were much- married. Not one of them possessed a talent that could survive outside the small pond of extreme privilege and extravagant riches in which they paddled.

Having collected his swans and celebrated his success a few months after the triumphant publication of In Cold Blood with the epochal Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, Capote began a long slide into middle-aged bloat. The combination of alcohol and drugs and constant high-society schmoozing is apparently inimical to serious literary endeavour. His plan to arrest that slide was to write a ‘Proustian’ novel about Babe Paley, Slim Keith etc, called Answered Prayers. Chapters of this unfinished roman-à-clef (memorably described by Picasso’s biographer John Richardson as ‘shit served up on a gold dish’) were published in Esquire in 1975 and 1976 and caused a sensation – not in a good way. In addition to being unfinished and godawful, the novel was a vicious, unprovoked betrayal of the glamorous women Capote claimed to love. Babe Paley was dying of cancer when ‘La Côte Basque, 1965’, the most egregious chapter, was published, full of poisonous revelations about her marriage to the media mogul Bill Paley.

Capote was warned by Gerald Clarke, his future biographer, that spilling the secrets of his swans would be a disaster; that they would recognise themselves and ostracise him and that he would lose his best friends. ‘Naaaah, they’re too dumb,’ Capote said. ‘They won’t know who they are.’

Leamer gives us potted biographies of the swans, and a wiki chronicle of Capote’s career. According to Updike, reviewers should provide enough direct quotation to give the reader a taste of the book. Here’s Leamer on Gloria Guinness:

From the day 38-year-old Gloria married Loel, she had a single-minded goal: to sit atop the swirling social world that she’d gained entry to just before the second world war, and which was again picking up steam now that the war was over. Although 44-year-old Loel was a member of the British establishment, the Mexican-born Gloria had no European social background. And she had, of course, trafficked with Nazi war criminals; that was a stain that was hard to wash off, no matter how beautiful and accomplished she was.

Leamer proceeds to forget all about that ‘stain’ – or maybe washing it off wasn’t so hard after all.

Two of Capote’s women friends (neither of them particularly swanlike) were brilliant and talented. Katharine Graham, the publisher of the Washington Post, was the guest of honour at the Black and White Ball. Leamer has almost nothing to say about her. Nelle Harper Lee lived next door to the young Truman in his hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. Later, while he was researching In Cold Blood, she was his indispensable assistant. She is of course world famous as the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, published in 1960. Leamer ignores her, too, though he does provide this baffling glimpse of their childhood friendship: ‘When Truman decided he wanted to be a writer and started pecking away diligently on his typewriter, he inveighed Nelle to write too.’ That’s just one of several of the book’s more unfortunate sentences. My favourite is a description of Perry Smith, eventually executed for the crime which In Cold Blood anatomises: ‘The uneducated murderer was a vociferous reader, obsessed with building up his vocabulary.’

‘Better to praise and share than blame and ban,’ says Updike. ‘If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines.’ Easy! George Plimpton’s Truman Capote (1997) is a rollicking oral history of the author’s fabulous rise and dismal fall; and Gerald Clarke’s Capote (1988) is lively, intimate, meticulously researched, clear-eyed and authoritative. Anything you might want to know about Capote’s women – including the brilliantly talented ones such as Graham and Lee – can be found in Plimpton and Clarke. Both books delight and instruct.

Scenes from domestic life: After the Funeral, by Tessa Hadley, reviewed

The cover image of Tessa Hadley’s fourth short story collection is Gerhard Richter’s ‘Betty’ (1988), a portrait of the artist’s daughter facing away from the viewer. It’s an apt choice for Hadley’s work, which turns on the fundamental unknowability of human beings.

The titular tale, about a widowed mother and her two daughters confronting reduced circumstances, is loosely inspired by Mavis Gallant’s story ‘1933’. Its climax, which pulls off the feat of being both shocking and inevitable, is a testament to Hadley’s skill as a storyteller. Some of the stories’ incidents are entirely internal: in ‘Cecilia Awakened’, a teenaged girl on a family holiday in Florence wakes up ‘inside the wrong skin’, suddenly aware of her parents’ shortcomings.

As ever in her oeuvre, Hadley masterfully uses the smallest details – of dress, food, décor – to convey class and character. In real life ‘we construct from those particulars the story of a life’, she has said, ‘necessarily incomplete, but full of rich suggestion’. Chekhovian shifts in points of view, such as between three adult sisters in ‘The Bunty Club’, offer narrative propulsion.

What is a mystery in real life – the inner world of others – is thrillingly revealed in Hadley’s fiction. ‘Dido’s Lament’ explores the awkward choreography between former spouses after a chance meeting. We’re in the woman’s thoughts, with the exception of a brief but revelatory peek into the man’s mind: ‘He had put together everything important, family and work and home, all so that Lynette could get to visit it some day and see that he’d managed to have a life without her.’

Hadley also harnesses fiction’s capacity to time travel. In ‘The Other One’, a dinner party encounter sheds light on a daughter’s misperceptions about the circumstances of her father’s death, with the story shifting to the present tense to recount the accident. In ‘Men’, a woman becomes aware of her estranged sister’s presence at the hotel where she works. Rather than making herself known, she reminisces about their childhood before scouring her sister’s room for clues about her new life.

Many of the stories are set in, or recall, the 1960s or 1970s, with social change providing a background for personal upheaval. As elsewhere in her work, including in the collection Married Love (2012) and the novels Late in the Day (2019) and Free Love (2022), Hadley vivisects domestic life, with women making various bids for freedom. Ashamed of failing to succeed as an opera singer, her Dido still concludes: ‘It really was better to be free. Or if it wasn’t better, then it was necessary.’

The collection ends on a contemporary note, capturing the peculiar texture of the days during the pandemic. ‘Coda’ is about a middle-aged woman fixating on a neighbour’s carer while waiting out lockdown with her elderly mother. Her projected fantasy transcends both the constraints of social distancing and a life devoid of ‘drama or joy or passion’.

Of the 12 stories in After the Funeral, a couple are less fleshed out than the others, seven of which have appeared in the New Yorker. Still, there is ample Hadley here to savour this summer.

An untrue true crime story: Penance, by Eliza Clark, reviewed

Remember the teenage girl who was murdered in Crow-on-Sea in 2016? A horrific story. Google it. Or the journalist Alec Z. Carelli, the guy who went to school with Louis Theroux, Adam Buxton and Giles Coren and wrote a book about it? Remember how it was pulled because of the controversy over the way he obtained some of his material? Well, the publisher has decided to release that book after all.

There will be no upset loved ones –except perhaps those who were affected by the true crimes mentioned

None of this is true. Instead, Eliza Clark, the author of Boy Parts and recently named by Granta one of the best of young British novelists, has written an untrue true crime book, a satire on true crime writers and true crime consumers embedded in an intelligently constructed, rapid lounger-by-the-pool piece of crime fiction.

It starts with a note from the publisher: ‘Artistic merit should not be erased from history simply for causing offence.’ The opening proper is a transcript of an American podcast: ‘I Peed on Your Grave, Episode 341’. Next come interviews, summaries, online comments, extracts from other documents, messages and newspaper articles, almost all of which are on the money. Clark describes one character whose daughter was involved in a murder as having written a Daily Mail article headlined: ‘Why Should I Be Embarrassed About Having More Than One Cleaner?’

Throughout the fiction are mucky dollops of real crime, rubbing our noses in our own behaviour. Damien Echols gets a mention, as do Jeffrey Dahmer and Ted Bundy. One character gives tours of Crow-on-Sea, but recalls how they ‘felt icky’ leading Jack the Ripper tours in London. The ‘Columbiners’ are in there, as are the online girls who feel they could have ‘saved’ Elliot Rodger. There are also the sick, deluded Cherry Creek obsessives. Actually those last are made up by Clark, but try to resist looking for them on Wikipedia.

The author is at her best describing this online world, as when she recounts one major event via Discord comments, or subtly explains the fascination with Slender Man and creepypastas (you really can look that one up). The biggest bump in the book is when it shifts to the more conventional and becomes, temporarily, straight crime fiction. ‘My interpretation of a key event’ is how this part is introduced, which feels like a creative cop-out. The story picks up again, but that section might have benefitted froma tighter editorial squeeze.

There are repeated pokes at the nature of true crime, particularly the journalist who admits to feeling like ‘a creep’ when asking people for interviews. ‘Carelli used the shared experience of losing our children to throw me off guard and harvest my content,’ says one regretful interviewee. But Clark shows the way in which things have moved on from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer. Now some of those who are written about can have a stronger voice than journalists, and if they get their message out there things can turn – as it does for Carelli when his story is scrutinised by those in it, prompting a Guardian journalist to ask him: ‘You’ve referred repeatedly to “emotional truth” – can you define that for me? What does that mean?’

For the most part, Clark avoids social media’s simplistic division of people into goodies and baddies. Instead, she describes characters’ thoughts and behaviour in ways that feel uncomfortably realistic, particularly the teenagers who grapple with shifts of power in their relationships. Who has it? Why do I not have it? The darkness in our brains is also confronted. Playing Sims 4, one character, Violet, locks a Sim teenage girl in a basement and keeps her there. She then introduces a Sim boy, and the pair have babies who are also locked in the basement: ‘Violet considered downloading a mod to enable incestuous relationships.’

People are drawn to that darkness in true crime, and Clark has simulated it well enough that readers will likely google fictional places on real maps. Importantly, nobody was harmed in the making of this book. There will be no upset loved ones –except perhaps those who were affected by some of the true crimes mentioned. The truth about these was probably needed to give depth to the illusion. Still, it is almost ethical true crime. For true crime fans who are not drawn to crime fiction it is a good vegan burger: good enough that there is no need to chop up a real carcass.

What, if anything, have dictators over the centuries had in common?

Big Caesars and Little Caesars is an entertaining jumble with no obvious beginning, middle, end, or indeed argument. But there is an intriguing book buried underneath it which asks more or less this: where does Boris Johnson stand in the historical procession of would-be strongmen or, as Ferdinand Mount calls them, ‘Caesars’? How successful was Johnson’s attempt – overshadowed by the Brexit noise, his personal scandals and his Bertie Wooster act – to turn Britain into a more authoritarian state?

Even when Caesars are kicked out, they weaken a country’s institutions

Mount, now 84, comes at this from a long Tory past that in recent years he has seemed to disown. Though he spent most of his career as a journalist and novelist, he was, also, incongruously, head of Margaret Thatcher’s No.10 Policy Unit in 1982-83, just as she began remaking the country. He described this stint in his 2009 memoir Cold Cream: My Early Life and Other Mistakes (a much better book than the new one). A cousin of David Cameron and nowadays a liberal Remainer, Mount isn’t keen on today’s Tory party.

Big Caesars and Little Caesars often reads like two almost unrelated books stuck together: an already outdated polemic against Johnson, and a collection of entertainingly retold secondhand research about historical dictators and thwarted wannabes. The book, Mount admits early on, ‘will jump about in a way that may disconcert some readers’. He disdains chronological order. He is overambitious, covering material on which he has no expertise. His riff on António Salazar’s Portuguese dictatorship, for instance, seems to have come straight from The Rough Guide to Portugal: ‘The concept of saudade – yearning, nostalgia – was all the rage, and so was the new melancholy song of love and loss, the fado (fate).’ I don’t think I’m being biased in recommending Strongmen by my Financial Times colleague Gideon Rachman, or The Despot’s Accomplice by Brian Klaas as better guides to today’s rash of Caesars.

Mount starts by suggesting he wants to find patterns across time: ‘How do these Caesars gain power? What are their vital ingredients? How do they normalise their breaches with constitutional tradition?’ But, as he soon admits, there are few patterns in history:

The local causes of breakdown which enable a would-be Caesar… to step into the breach are strikingly varied…. Secondly, the causes are not tied to any particular stage of economic or social development.

It is true that history is patternless, but that exacerbates the patternlessness of this book. In the hands of an old-fashioned Whig or Marxist historian, Big Caesars and Little Caesars could have marched more satisfyingly to a resounding (albeit wrong) conclusion.

As Mount explains, would-be Caesars can emerge any time, in any society. In fact they find surprisingly fertile ground in established democracies. As Max Weber noted, once you directly elect the leader, you create opportunities for charismatic individuals who can charm the electorate. No wonder that Johnson argued, in defiance of the British constitution, that as prime minister he had a personal ‘mandate’ from voters. Uncharismatic figures, such as Salazar, do better in dictatorships, where voters’ tastes don’t matter.

The most recent Caesar-friendly innovation is social media. Mount quotes Donald Trump: ‘I love Twitter… That’s the only way I have to communicate. I have tens of millions of followers. This is bigger than cable news.’ Mount writes:

Twitter plus Fox News provided Trump with unmediated access to his core voters, a closeness that probably hadn’t been available since ancient Greeks and Romans crowded into the Agora and the Forum to hear it straight from Demosthenes and Cicero.

Mount’s attempts to connect Johnson, and occasionally Trump, with past Caesars are underwhelming. Most of the parallels are obvious: e.g. Caesars despise parliaments as talking-shops for the uncharismatic and put out lying propaganda. Jacques-Louis David’s painting of Napoleon crossing the Alps on his white horse, for instance, conceals the fact that Boney and his men slid down the icy Great St Bernard Pass ‘on their bottoms’.

But Mount does occasionally cast light on the Caesarian modus operandi. One commonality these people share is contempt for their own supporters. Here is Charles de Gaulle in retirement: ‘The French no longer have any national ambition… I amused them with flags.’ And Hitler:

The receptivity of the great masses is very limited, their intelligence is small, but their power of forgetting is enormous. In consequence of these facts, all effective propaganda must be limited to a very few points and must harp on these in slogans.

And Trump’s adviser Steve Bannon told the designated ghostwriter of a Trumpian book about the Deep State: ‘You do realise that none of this is true?’ Johnson and Trump, too, aimed to fool some of the voters all of the time.

Many Tories will reject the categorisation of their beloved ‘Boris’ as a would-be Caesar – albeit, in Mount’s own terminology, only a ‘Little Caesar’, who seeks a more authoritarian government rather than full-blown dictatorship. Johnson doesn’t look Caesarian. But Mount quotes Johnson’s former employer at the Telegraph, the ex-convict Conrad Black: ‘He’s a fox disguised as a teddy bear.’

Mount makes a good case for Johnson’s strongman impulse. His argument rests on Johnson’s ‘five acts’ to increase the power of prime minister – a position that he expected to keep for nearly a decade until he tripped himself up with partygate. To enhance the PM’s power, he wrote into law what Mount describes as a long-held project of the Tory right, egged on by the instinctively authoritarian tabloids. Johnson set about extinguishing all rival sources of power. He got out of the EU; hounded dissident MPs from his party; cowed the civil service by pushing out the cabinet secretary and several permanent secretaries; reduced the power of judges to review the government’s actions; attempted voter suppression by making photo IDs compulsory for voting but not recognising types of ID that younger anti-Tory voters tend to have; gave government some power over the previously independent Electoral Commission; and gave police more scope to criminalise demonstrations. He pushed much of this package through parliament in spring 2022 while everybody else was obsessing about partygate.

Even when Caesars are kicked out, they weaken a country’s institutions. They show would-be successors that in every country there is appetite and opportunity for a strongman. They enlarge the boundaries of the possible. Once one Caesar has lied to parliament or attempted a coup, lying and coups lose some of their stigma.

Still, as Mount shows, Caesars are often stopped. To him, the best safeguard is parliament. Worryingly, it has been weakened by decades of derision. Recent approval ratings of the US Congress are 20 per cent, and for Britain’s parliament 23 per cent.

Mount ends by recounting the ancient ritual by which the door of the Commons is initially slammed in the face of Black Rod, ‘the major-domo of the House of Lords’, to symbolise the Commons’ independence. Only after Black Rod bangs the rod three times on the door do MPs follow her (the current incumbent is Sarah Clarke) to the Lords for the King’s Speech. Mount concludes: ‘I used to think that the whole performance was the kind of mummery we didn’t need any more. But now I think we need it more than ever.’

Alex Salmond to launch pro-indy TV show

They say all publicity is good publicity. But perhaps that sentiment isn’t shared by those in Bute House at the news that Alex Salmond is launching his own pro-independence TV programme. The former First Minister will become the latest politician to turn TV presenter this week when he launches his new show on Thursday: ‘Scotland Speaks – with Alex Salmond.’ Like a Tartan Tucker, he will be hosting it on social media from Slàinte Media’s brand new Glasgow studio. But with the National having mastered the art of Scexit propaganda, is there really any need for more separatist media coverage?

Salmond certainly thinks so. ‘At an important time in Scotland’s story, both the Scottish and Westminster parliaments seem preoccupied with navel-gazing and side issues,’ he stormed. Side issues like, er, a second referendum, Alex? What ‘Scotland Speaks’ will actually cover remains a mystery. Salmond has said that the ‘big challenges’ and ‘opportunities facing the nation’ will be thrashed out, and his co-presenter and Alba party chair Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh added that ‘there is no shortage of issues just now’. Just not the ones he’s been talking about for the past few years…

Still, Salmond is no beginner when it comes to presenting TV shows. The ex-SNP leader previously formed a long-time infamous alliance with the Russian state-owned news network, Russia Today. Having hosted ‘The Alex Salmond Show’ for five years, it took Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine to make Salmond surrender his prized programme. Talk about the real victims of war…

Will ‘Scotland Speaks’ hit it off with viewers? There is certainly an increasing number of disillusioned SNP voters on the rise, and perhaps Salmond hopes his new show will convince them to make the leap to Alba. More likely, viewers will flock to the new show in the hope he divulges juicy gossip on the Scottish National party.

The jury’s out on whether this shock Jock will achieve any real success from his new TV show. But if it annoys the Nats, that’s good enough for Mr S…

Nato’s members still don’t see eye to eye on Ukraine

US President Joe Biden flew into Vilnius, Lithuania early on Tuesday with a big task ahead of him: to keep Nato as united as possible at a time when the alliance is fractured on a bunch of major issues. Foremost among them is when and how to provide Ukraine a path toward eventual membership.

In public, the two-day session will be full of group photos of smiling heads of state and warm words about the alliance’s resolve in the face of Russian aggression. But behind closed doors, where the actual business is done, difficult conversations will certainly be had. While Nato’s 31 member states (soon to be 32 when Sweden’s accession process is complete) have pledged to come to one another’s defence, the fact is that some of these countries are coming to the table with different positions.

Whether Zelensky accepts this dispute is irrelevant, it is there whether he likes it or not

As expected, the possibility of Ukrainian membership in Nato is getting most of the media attention and sucking up all of the oxygen in the room. In 2008, during a previous heads of state summit, Nato declared in writing that Ukraine, as well as Georgia, would become Nato members at some undefined date in the future.

The Ukrainians have been waiting for the last fifteen years for the alliance to make good on that written pledge. But the question of when to do so has been in a frequent thorn in the alliance’s side. Russia’s decision to launch a war in Ukraine last year means that Nato membership is simply not feasible for the Ukrainians as long as the fighting goes on: the alliance has a decades-long policy that aspiring members need to resolve their territorial disputes before their applications are given serious consideration.

President Biden restated that policy during an interview before his trip to Europe. Simply put, if Ukraine was granted membership now, Nato would automatically be in a war with a nuclear-armed Russia.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky understands all that. Yet he remains defiant, if not angry, about what he views as the alliance’s cautious approach. Before heading into the summit, Zelensky tweeted that it would be ‘unprecedented and absurd’ if Nato refused to at least give Kyiv a clear, measurable time-frame on when membership would be an option.

Zelensky isn’t alone in his angst; Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, one of Zelensky’s most high-profile allies within the alliance, has gone to bat for Ukraine in the international media, telling the Financial Times last week that ‘concrete steps’ need to be taken so the Ukrainians can go home at night knowing that the world’s most powerful alliance is in its corner (although the more than $70 billion [£54 billion] Nato has devoted to the Ukrainian military over the last 17 months should have delivered the message already).

Nato, however, works on consensus. That means any member state can bring things to a halt or raise concerns that force the alliance to rework the problem. The blunt reality is that Nato’s 31 members still don’t see eye-to-eye on the Ukrainian membership question. Whether Zelensky accepts this dispute is irrelevant, it is there whether he likes it or not.

The US remains resistant to offering a clear timeline for its own reasons. Because Washington serves as the heart, lungs and muscle of Nato as a whole, it (rightly) treats the issue of Ukrainian membership, now or in the future, as serious business. As much as the US wants to see Ukraine prevail, it also doesn’t want to fight the world’s largest nuclear power or put itself in the position whereby that fight becomes more, not less, likely.

Germany is on the same wave-length. ‘The time is not right at this summit for an invitation to Ukraine, for concrete steps toward membership,’ a German official said on Monday. ‘There is no consensus on this among the allies either.’

Beyond Ukraine, the allies will also be knocking heads over Nato’s future trajectory. More specifically, whether the alliance should be spending more time and resources on potential security problems in the Asia-Pacific region (i.e. China).

In 2022, Nato name-dropped China in its Strategic Concept document, listing all of the ways the Asian power is subverting the so-called rules-based international order. Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has devoted the last few years of his decade-long tenure to trying to strengthen the strategic bonds between Nato and Asian countries like Japan and South Korea. He invited the two countries to last year’s Nato heads of state summit (Japan and South Korea will be attending this year too). Nato was also flirting with opening a satellite office in Tokyo, partly to reinforce those ties.

Yet some Nato members sour at the idea of the alliance getting involved in Asia’s business. French President Emmanuel Macron has stated more than once that Asia isn’t in its remit. Nato, after all, is an acronym for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, not the North Atlantic and East Asia Treaty Organization. Why the alliance would start expanding to Asia, particularly at a time when Europe is still hosting its deadliest war since 1945, almost belies belief. Macron feels strongly about this: several days ago, the French government announced that it objected to opening a Nato office in Tokyo. The Japanese took the message in their stride.

The summit is occurring as we speak, so what will result from it is still very much up in the air. What can be said for certain is that many of the issues the allies are discussing away from the cameras will continue to percolate after the summit concludes.

The BBC presenter feeding frenzy

Rishi Sunak has touched down at the Nato summit, but there’s only one question journalists want to ask him about: the allegations that a BBC presenter paid a young person for explicit photos. The claims are ‘shocking and concerning’, the Prime Minister said, adding that he has been assured the BBC’s investigation will be ‘rigorous and swift’. Yet amidst the ongoing and frantic speculation – and endless chatter on social media – the silence from officialdom, the police and the news media as to who the man at the centre of the story actually is has been deafening.

A veritable feeding frenzy continues online, not to mention on foreign websites speculating on who the unlucky man might be. The result has been predictably toxic. As in a Hercule Poirot whodunnit, everyone is falling under suspicion. BBC bigwig after BBC bigwig has been forced to issue an embarrassed statement saying that, whoever it was, it wasn’t him. The BBC’s director-general Tim Davie has said he ‘wholly condemns the unsubstantiated rumours being made on the internet about some of our presenting talent’. But in this information vacuum, is it any wonder that people are speculating?

An unsustainable silence continues in the media – and the feeding frenzy continues online

We don’t know for sure why the Sun, which first reported the claims, has kept quiet on the identity of the ‘household’ name presenter. Vague fears of libel and privacy laws have doubtless combined with a feeling of omertà among the great and the good, and, for some, a perception that it was only fair to protect the good name of a household figure unless and until he appeared in court.

Yet the real cause of this silence, I suspect, probably has something to do with the increasingly draconian restrictions emanating from human rights laws on what we, the public, are allowed to read.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, protecting private and family life, gave the UK government some worries when it signed the Convention in 1950: in retrospect the government was absolutely correct. In the last thirty years or so, the interpretation of Article 8 has become bloated beyond recognition, so that today a person must be allowed legally to suppress information about himself on the basis of no more than what Strasbourg judges see as a ‘reasonable expectation of privacy’. This can cover such things as revelations of casual affairs and embarrassing public photographs, something that has made the tabloid press less interesting of late.

Eighteen months ago, our own Supreme Court, aligning with Strasbourg thinking, held that an American businessman had a right to prevent any mention being made of the fact that he was under investigation in relation to claims his company had been involved in corruption. It also confirmed that, in principle, a person had a right to use the law to keep under wraps the fact of any criminal investigation against him short of charges being brought.

This is worrying. Human rights, we must always remember, are by nature anomalous and exceptional: they are so important as to justify giving an end-run around the democratic process. Sometimes this is all very well: think extreme cases, such as forced sterilisation, torture or deliberate state murder. What is not right, even though judges in Strasbourg and London now do it however, is to apply this kind of reasoning to lesser matters, such as protecting the amour propre of businessmen (and media personalities) who would rather the public was kept in the dark about any investigations being made about them. Balancing such demands for secrecy against the freedom of the press and free speech generally is fundamentally a matter of social policy, which should be decided upon by electors and their representatives.

Whatever human rights law may say, insisting on obscuring certain information is simply misguided. For one thing, it rests on a crabbed view of the function of the media. In any open society, people are naturally and rightly curious about their fellow citizens, the institutions of the society they live in and those involved with those institutions. But the idea that the press should exist to satisfy this curiosity is anathema to some judges. On the contrary: trouble must be avoided, curiosity deprecated, and only the public interest as determined by them can justify spilling embarrassing beans. Or, to translate, they hold the rather prim attitude that we the public should on principle only get the information the great and the good think is good for us.

If we had been allowed to know from the beginning who the man is in the Sun‘s story, most of this chaotic fallout could have been avoided. News is forgotten fast: without the obsessive secrecy, public attention would have moved on to another story. But, as it is, an unsustainable silence continues in the media – and the feeding frenzy continues online. Meanwhile, innocent people are being traduced. Supporters of keeping the names of those accused of impropriety secret must pause and reflect: is this current situation in anyone’s interest?

Who’s to blame for rising mortgage costs?

Mortgage costs have reached a 15-year high today, with the average two-year fixed deal hitting 6.66 per cent – the highest level since the summer of the 2008 financial crash. But today’s mortgage news is being pegged to far more recent history, as average deals just topped their peak from last autumn, when Liz Truss’s mini-Budget sent interest rate expectations soaring, and mortgage offers along with them.

Truss’s premiership came to an end because so many numbers were spiralling upward, including the cost of government borrowing, mortgage repayments, and the number of Tory MPs who – amid all the chaos – were simply not going to take instructions from her government. Rishi Sunak’s promise when entering No.10 was not just to restore credibility, but to calm the markets and get these costs under control. It seemed to work at the start, as borrowing costs fell – as did mortgage deals – and MPs (broadly) fell in line.

Now that average mortgage deals are not far off 7 per cent – and gilt yields have steadily climbed back up, too – has Sunak failed to make good on that promise? Some Trussites see today’s news as vindication that they were right (or at least, not completely wrong); that the blame placed at Truss’s feet for surging costs was due to other factors. Steerpike reminds us that Sunak made mortgage rates his big talking point during the leadership campaign last summer, setting up an online calculator (now deleted) so people could see what would happen if Truss’s fiscal policies led to a surge in rates of around 7 per cent – a figure one of her economic advisors, Professor Patrick Minford, said at the time was possible. If that calculator still existed, it might be showing figures even more financially painful than what would have been calculated last year.

One of the many consequences of higher interest rates – currently expected to peak around 6.5 per cent – is higher mortgage payments. So why are expectations soaring now? Last autumn, they shot up as a direct consequence of government announcements. Not only had Truss’s government just announced an Energy Price Guarantee which – at the time – was estimated to be one of the biggest handouts pledged by a British government; it was also announcing tax cuts (small in comparison to the spending promises), all on the assumption they could simply borrow the money to do so. Never mind that interest rates were starting to rise across the world, which should have been a signal that this was not necessarily the time to test a spending spree. Team Truss not only thought they could continue to borrow with impunity, but that markets would see what the government was trying to do and happily finance the transition from a stagnant economy to a high-growth one.

Moreover, her economic advisors were in agreement that rates actually needed to rise. Though never explicitly stated by Truss, the overarching goal was to rebalance fiscal monetary policy, loosening the former to force the latter to tighten: an over-correction to the ‘disastrous mistake’ to keep rates artificially low, Minford told me last September ahead of the mini-Budget.

There’s no doubt Truss and her team were onto something: the liability-driven investment (LDI) pensions scare, the regional banking crisis and a growing mortgage crisis are all consequences of keeping rates so low for so long. But that over-correction went a bit too far, as Truss’s fiscal announcements led to an almost-immediate surge in borrowing costs, as international markets demanded a higher return for what they saw as sloppy spending behaviour.

The same cannot be said of Sunak and his government. The controls on public spending are much tighter. He and his chancellor’s desire to make the Treasury's book’s look slightly more appealing have delivered a different kind of fiscal pain: a tax burden that has risen past Boris Johnson levels, currently at a post-war high.

Still, interest rates are rising, and peak expectations keep going up. But this time round, it's not the sharp, shocking spike we saw last autumn, but rather a steady and persistent climb. That’s because the reasons behind the expectations are different: they are not driven by some fiscal experiment currently taking place within the government. Instead, they are driven by stubborn inflation, which is not falling anywhere near as fast as originally predicted.

Fears across Whitehall are growing that Sunak may not even meet his pledge of ‘halving inflation’ by the end of the year

No one expected such a difficult battle with inflation last autumn, or even at the start of the year, when the headline rate was expected to fall close to the Bank’s target by 2 per cent by the end of 2023. Now, the Bank can’t stress enough that its inflation forecasts are skewed to the upside, as fears across Whitehall grow that Sunak may not even meet his pledge of ‘halving inflation’ by the end of the year.

As it has dawned on the Bank that it was far too optimistic in its original predictions, its actions have had to become more hawkish, bringing in its 13th consecutive rate rise last month, taking the bank rate to 5 per cent. This is causing the spikes we’re seeing in mortgage deals, happening so fast that major banks are having to pull mortgage offers with virtually no notice, as rate expectations continue to rise.

The problem for Sunak is not accusations from Trussites that he was wrong and she was right, but rather that he has strayed away from his leadership campaign narrative, which was much more pessimistic but ultimately correct in its analysis about inflation. Last summer, Sunak openly admitted that inflation was largely out of everyone’s hands, and the best thing governments could do was keep a tight grip on the spending reins, so rates wouldn’t need to rise higher than necessary to tackle it. This year, he has decided to suggest instead that government has the power to halve inflation.

As a result, his government is increasingly being blamed for stubbornly high inflation and rising rates, when these things primarily sit with an independent Bank. As a result, he’s far more open to attack, not just from disgruntled MPs, but far more importantly, from the public.

Tories fight over Illegal Migration Bill

The Illegal Migration Bill is back this afternoon for ‘ping pong’ – the final stage of its legislative passage where MPs and peers bat amendments between their respective chambers until a compromise is found. There were 20 such amendments for the government to deal with and there is still a chance that some key Conservatives might rebel tonight. Ministers want to overturn 15 changes.

Two of the loudest critics are, inconveniently, former home secretaries

Two of the loudest critics are, inconveniently, former home secretaries. Theresa May has criticised the Bill throughout its passage and it is still not clear whether she will vote with the government or rebel tonight. She never indicates how she will vote before she stands up in the Commons, which means there will be a moment of drama when she stands up to speak. Her main beef – and that of former Tory party leader and work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith – is that the legislation waters down protections for victims of modern slavery. So far there has been no concession offered ahead of tonight’s ping pong. Duncan Smith says that he is likely to vote against the government on this: ‘I’m quite in favour of the Bill going through, but we are still in discussion with the government on the modern slavery amendment. They’ve got to rethink this as it weakens the chance of getting prosecutions and to go after the very people who are getting them on the boats in the first place.’ He has been told that ministers will put protections into guidance – but is unhappy with that because guidance is not produced until after the legislation is on the statute books and is of course only guidance rather than something that is enforceable.

Another former home secretary, Priti Patel, this morning tweeted that ‘we were told that the Illegal Migration Bill would ‘stop the boats’. Key pillars of that Bill have now been abandoned.’ When I spoke to Patel today, she added that one of the big failures of this government was not having a proper plan for its delivery: ‘Resolving the issue of illegal migration has never been simple. There is no one single solution to stopping the small boats which is why a package of end-to-end policy and operational measures to bring lasting change to the system is vital. This should also cover asylum accommodation as outlined in the previous policy statement the New Plan for Immigration.’

Her tweet has not gone down well with government sources, who have hit back and told Coffee House: ‘Clueless. And not like her record of three years in office is much of a defence on this topic?’ Patel hasn’t actually voted on any stage of this legislation, which at least means that she isn’t a threat in a parliamentary sense: but of course if this legislation does make it onto the statute book within the next week, as the Home Office hopes, then what follows will merely be a public debate – but it could become a blame game if the battles in the courts and over the wider implementation don’t go to plan.

Other Tory MPs are a little more relaxed. Danny Kruger, now chair of the New Conservatives, had been calling for ministers to use the Parliament Act to ram through the Bill in the form it left the Commons rather than the much-amended version the Lords are sending back. He says he is now largely content with the legislation and that the government is defending the principle of the Bill. ‘I think our robust defence of the Bill has ensured the government is not caving in on the main provisions – because there would be a big rebellion then.’ The bigger problem, of course, is if the Bill doesn’t actually stop the boats – even if the Supreme Court does rule in favour of the Rwanda policy.

America’s fierce guilt for slavery is understandable – we mustn’t import it

I love American roadtrips. They are the ideal way to visit 96 per cent of the country, which is determinedly built (for good or ill) around the desires of the car driver. The brilliant roads, the endless motels, the hideous car lots that blight most of the cities (making parking a doddle, even if they ruin the actual towns), they all ensure that driving is easefully delightful.

Even in the most nondescript hotel in the most ahistoric corner of America, you will happen upon the surreal, haunting legacy of slavery

A roadtrip is also the best way to understand America, and my recent trip along and around the Mason-Dixon Line – the great geographical/political divide which once (still?) sunders the old Union states from the old Confederacy – taught me the depth, strangeness and profundity of white America’s guilt: vis a vis America’s slaving past.

The peak moment of eeriness probably came at sunny, splendidly situated Monticello, Virginia, which is the Unesco-listed estate designed and inhabited by the American founding father, Thomas Jefferson. Amongst other things, Jefferson was America’s third president, and he actually wrote much of the declaration of independence, with its sonorous avowal that ‘all men are created equal.’

There’s a copy of the declaration at Monticello, there’s also a death mask of Cromwell (a hero of Jefferson’s), some quaint and exquisite scientific instruments (Jefferson was a true Renaissance man), plus a pair of elk antlers brought back from the Wild West by explorers Lewis and Clark. On top of that there is a brief guided tour where the guide refers to the workers on the estate as ‘members of the enslaved community’.

I confess, when I heard this tormented phrase, I did a double take. Maybe I’d misheard. But no, the guide said it again. He avoided the simple word ‘slaves’. He called the slaves, ‘members of the enslaved community’. Like the slaves at Monticello were something like ‘the Sikh community’ in Britain, a bunch of willing migrants who casually wandered up and asked if they could wear shackles.

As I continued my tour of Monticello, marvelling at Jefferson’s enormous cellars where he kept his beloved champagnes, I think I worked out why you would use such a peculiar, ambiguous phrase. I don’t believe it is because the guides at Monticello are trying to diminish the horrors of slavery, I believe it is because they are trying to treat it as decorously, politely, and humanely as possible. And they are failing: because slavery is so cruel and outrageous it cannot be semantically neutered. The horror abides, always.

For a sense of this irredeemable wickedness you just have to wander Monticello’s leafy plantation, where you will happen upon a facsimile of Sally Hemings’ tiny wooden cabin, where she likely lived, for a while, with members of her family. Who was Sally Hemings? For a long time she was simultaneously Jefferson’s slave and ‘mistress’, and mother of several of his children (offspring who, by law, automatically became Jefferson’s property, as the enslaved children of his slave concubine – though Hemings sought their freedom).

Did Sally Hemings have much say in this arrangement? It seems doubtful to me. She was, after all, a slave. Jefferson owned her just as he owned the cattle that grazed his 5,000 acres. Perhaps it is best to call her a ‘member of the raped community’. And remember, she, like her brothers, cousins, friends, was a slave of Thomas Jefferson: the man who actually wrote ‘all men are created equal’. Did Jefferson feel a twinge of hypocrisy as he penned this in Philadelphia, or did he mentally annotate the document, without writing it down, ‘all men are created equal, apart from profitable members of my enchained community’?

It ain’t just Monticello where the weirdness and evil of slavery loomed large on my road trip. It was pretty much everywhere. Take Alexandria, a rather lovely, and unusually walkable old colonial town, a few miles south of DC. With its seafood bars and Georgian terraces, prosperous Alexandria feels like a particularly charming town in the English southwest, until you come to a plain looking house, last remnant of the infamous Franklin and Armfield slave pen, whose owners became, from their trade, some of the richest men in the USA.

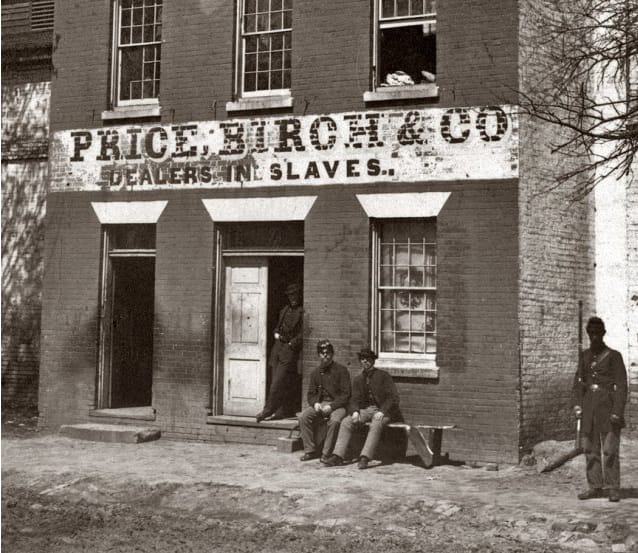

There is a photo of this slaving company in its last guise. The signage casually says: ‘Price Birch & Co Dealers in Slaves’, the same way a photo of a shop in Victorian London, from the same era, might say ‘Dealers in Linens and Cloths’. The photo is indescribably chilling.

And so it goes on, as you wind along the Mason Dixon line. Slavery, the effects of slavery, the underlying evil of slavery, is ubiquitous: like a seam of dark mud left by an apocalyptic flood. In Cincinnati the line is marked by the great Ohio river which divided ‘free’ Ohio from the ‘slave state’ of Kentucky. Escaped slaves would flee across this dangerous river, but even if they made it to Ohio, they weren’t safe. For years the Fugitive Slave Act meant that slave owners were allowed to head north to recapture their straying human livestock – and northerners were obliged to assist them. Some slave owners actually came hunting for the children of successfully escaped slaves.

Even in the most nondescript hotel in the most ahistoric corner of America, you will happen upon the surreal, haunting legacy of slavery. At one point I stayed in a Holiday Inn Express in Pennsylvania, so I could go see Frank Lloyd Wright’s nearby Fallingwater house in the morning. At my generic buffet breakfast, where I served myself coffee, juice, and bad croissants, I was given a bill with options to tip 10, 15, 30 per cent, etc. There did not seem to be an option not to tip. Even though no member of the hospitality community had actually done anything to directly serve me.

Why is tipping so uniquely pervasive and ridiculous in America? A lot of tourists ask this, I can give you the answer: slavery. When the slaves were emancipated after the Civil War, millions went north to get paid work. The locals weren’t especially welcoming, so the only jobs the freed slaves could find were often in bars, hotels, restaurants. As the workers had lately been slaves, the managers felt no obligation to remunerate them properly, so they paid them a pittance, and the workers were expected to make up their wages by being so servile they were generously tipped. The tradition endured, and that’s why you have to tip everywhere and everyone in the USA, today.

Once you begin to grasp the grim and universal scars, legacies and ramifications of slavery in America, you begin to understand why Americans – white Americans in particular – are so neurotic, allergic, jittery, and guilt-ridden about the issue, and why wokeness about race, in all its religiose bizarrerie, was birthed in the USA. I have written elsewhere how slavery was universal, across history and around the world, and how some of it is absurdly ignored. Nonetheless, slavery can feel like the Original Sin of the American Republic. Slavery is actually written into America’s founding document, the US Constitution, with its opaque references to certain voters worth three fifths of proper voters. The semi-humans are the slaves in the South.

Should Britain share in this terrible sense of Original Sin? I believe not. Of course, we were a huge slaving nation, like the French, Portuguese, Arabs, Chinese, everyone else: this is a source of deep shame. But the fact is, slavery in the modern sense was forbidden in the United Kingdom.

Moreover, and more importantly, Britain made a purposeful redemption of its sins, and this is spelled out, once again, right on the Mason Dixon Line. If you go into the excellent Freedom Museum in Cincinnati, which looks across the Ohio river to the slave state of Kentucky, you can read how the British abolished the slave trade in 1807, and then spent many millions – serious chunks of British GDP – eradicating slavery in all the oceans of the world, as best we could. This is why the slavers of Alexandria got so rich: when the Brits stopped the slave boats from Africa, a huge internal US slave trade developed, marching millions of coffled slaves from Virginia and the Carolinas, down to Cottonland in the Deep South.

As for those escaped slaves who fled across the river, the museum also explains their fate: their best bet was to continue their furtive race, until they reached genuinely free territory. In other words: usually British territory. The Bahamas for some, Canada for most.

In that light, I believe Britain can look at the legacy of slavery with at least a semblance of neutrality. We did some truly evil things, but we did some genuinely good things, we therefore have no need to import the one-sided neuroses of the USA on this tragic history, any more than we should import their terrible culture wars over abortion. America, unfortunately and uniquely amongst western democracies, owns a much darker, larger slaving history, which they have to confront. Whether they can ever truly overcome it, I have no idea. But I fear that using coy phrases like ‘members of the enslaved community’ probably isn’t going to do the job.

Why are we so obsessed with TV presenters?

The mucky allegations about a ‘household name’ BBC star – who is said to have paid thousands of pounds to a teenager for sexually explicit pictures – has exposed our obsession with TV presenters. We invite these people into our homes every day. Stars we never meet become familiar, a part of our lives and daily routines. Now, for one of these presenters, their world has come crashing down, and we can’t get enough of it.

There are plenty of questions hanging over this story: we still don’t know the identity of the presenter concerned, even if social media is awash with a list of suspects. And we don’t know whether the allegations are true. But there’s no doubt that we find presenters caught up in scandals fascinating. There is also something deliciously exciting about such stories. It’s futile to pull a shocked face and pretend otherwise.

Perhaps our obsession is because TV presenters are an odd type. Presenting, when you stop to consider it, is a strange job. The presenter’s job is a simple one: to read an autocue. Yet, for this task, they are paid a fortune – hundreds of thousands of pounds a year – and attract loyal, even cult followings.

In recent years, these figures have multiplied like rabbits and become more and more central to their shows, and to our culture in general. As Julie Burchill has written, the logical endpoint of all this would be a TV programme called Presenters Present Presenters. Increasingly, as with so much else in our cultural diet – superheroes, stand-up comedians, the SNP – what was once an amuse-bouche is plated up as a main course. We now have the likes of Carol Vorderman, Kirstie Allsopp, Gary Lineker and Chris Packham anointing themselves – incredibly – as our moral arbiters.

The neutrality and squeaky cleanness of many of these on-screen roles means the contrast with what my gran used to call ‘mucky behaviour’ is severe. Disgraced Blue Peter presenters are the great exemplars of the syndrome. The juxtaposition of gluing tinsel to washing up liquid bottles and cavorting with male strippers in a gay bar, or being secretly filmed snorting cocaine is irresistibly comic. We’ve all seen, and if we’re honest felt, the little frisson that ripples around a group of people when we hear such news.

This conflict between cuddly national figure/treasure and reality happens too frequently to be a coincidence, surely? Is there something about the people – oh let’s face it, the men – who are drawn to this curious role? They are famous simply for saying ‘and now this’, or for pulling the exactly appropriate face for each news story from ‘holidaymakers crushed by collapsing cliff-face’ (oh how awful) to ‘adorable tot hands bouquet to Princess of Wales’ (oh how sweet). Is there something about wanting that role and being something of a secret wrong ‘un?

Perhaps, though, this is to put the cart before the horse. Could it be that it is the role of presenter which does something to people? A life in the public eye, where you are required to be stultifyingly bland, a lowest common denominator everyman, where you have to constantly be neutral and formal, or at least pretend to be. Yes, we the public love the mask slipping, for its savoury comedy value. But what about the men behind the mask?

As Iggy Pop observed in his 1977 song Some Weird Sin, ‘Things get too straight, I can’t bear it’. He goes on that ‘The sight of it all makes me sad and ill. That’s when I want some weird sin’. This is followed by what I think is the key line of this splendid lyric – ‘Just to relax with’.

I think Mr Pop hit on something very profound there, about male sexuality and social roles. The contrast between things getting too ‘straight’ and some weird sin is the whole point of such activity – and the contrast is particularly great with TV presenters. It is both the spur and the spice. It is what adds the piquancy.

If the allegations transpire to be true, what we find here in this latest scandal is our old friend, the imp of the perverse. The desire to do something incredibly out of character. To have something of one’s own, away from the public gaze. It’s amusing that these aberrations are often referred to, even by the perpetrators, as ‘a moment of madness’, because perhaps some men indulge in them, defying all logic, to keep themselves sane.

The exact nature of the activity is, I suspect, often not important. The big factor is the inconsistency with the public image. Having to be perkily polite, the model of decorum, day after day, to everybody you encounter, must surely be exhausting. I think such men might feel subconsciously that their personality and individuality has been blotted out, and it is this that sparks some sort of crazy, ‘stupid’, reckless reaction.

We’ve seen this in many men who hold down important jobs. What else could explain why Tory MP Neil Parish clicked that porn link in the chamber of the House of Commons? What the hell was going through the head of his colleague David Warburton when a woman who spoke fluent Russian plied him with strong drink and served him up class A drugs?

Activities like this are suicidal for men in the public eye, and yet these stories keep on coming. This latest scandal is unlikely to be the last.

Flashback: Sunak mocks Truss over mortgage rates

It’s a red letter day for Rishi Sunak. No, he hasn’t succeeded in fulfilling any of his five priorities. Instead, the average two-year fixed-rate mortgage has today passed the peak seen in the wake of the Truss government’s mini-budget. Mortgage rates have soared in recent months, following the Bank of England’s interest rate hikes to try to tackle rampant inflation. Two-year fixed deals have now reached 6.66 per cent on average – a level not seen since August 2008.

That rate is of course higher than the 6.65 per cent reached on 20 October last year, when Tory MPs were in full meltdown. Back then some Sunak allies were crowing that they had seen this all coming: that her unfunded tax cuts made this inevitable and that a U-turn was needed. Throughout the summer leadership campaign, Rishi Sunak himself unveiled an interactive calculator to show how much voters’ mortgage monthly payments would rise with 5 per cent interest rates – a figure which, er, the UK hit in June this year. Mortgage brokers believe the average two-year fixed rate will now peak around 7 per cent and not fall until 2024.

Mr S wanted to go and use the calculator to see what would happen to his mortgage if rates continued to rise under Sunak. But sadly the website was quietly deleted a couple of months ago. Funny that! As a source close to Truss told the Times: ‘We now find ourselves with higher interest rates and stagnant growth, with none of Liz’s reforms being enacted’. What were the last nine months all for, eh?

Urgency drives the day at the Vilnius Nato summit

Rishi Sunak heads to Lithuania today for the Nato leaders’ summit (which means he will be missing another Prime Minister’s Questions). The trip comes after Sunak met one-on-one with president Biden at 10 Downing Street – a visit which is being heralded in government as a success after the pair avoided amplifying a lingering disagreement over the US government’s transfer of cluster bombs to Ukraine.

While Sunak was critical of the use of the weapons ahead of the visit (a legal obligation of the UK government as a result of its membership of the Convention on Cluster Munitions) he chose not to bring it up and reprimand Biden on the visit. This allowed the US president to wax lyrical about the relationship being ‘rock solid’.

The window of opportunity to try to end the conflict and help Ukraine could be short

As for the Nato summit, the reason it is being held in Vilnius is, of course, down to the rotation of locations for these events. But it also comes at a time of change in the EU’s political geography where the countries in the east are growing in geo-strategic influence.

So far, the Baltic States have taken the more hawkish position on Russia when it comes to the Ukraine war (as my interview last year with Lithuania’s foreign minister shows). The fact that Poland plans to increase its defence spending to 4 per cent of GDP this year – which would, on current figures, make it the highest level in Nato – is another indicator of the shifting power balance. There are some signs that it is having an impact on countries to the West such as France, with Emmanuel Macron appearing to harden his position. In May, he suggested for the first time that there ought to be a ‘path’ to Nato membership for Ukraine.

While it’s Sweden’s membership of Nato that looks imminent (with Erdogan dropping his resistance), membership for Ukraine is one of the topics that will be on the agenda in the coming days. US resistance means it remains unlikely to be granted anytime soon, with Biden preferring to adopt an approach more akin to the US relationship with Israel and supply it with what the country needs where possible.

Sunak will use the summit to call for more countries to spend at least two per cent of their GDP on defence. Should countries such as France, Germany and Italy fail to match those already doing so, it will only add to the sense that the power balance is shifting when it comes to those leading the conversation about what comes next.

However, one of the reasons for urgency is that ultimately, even if the more hawkish voices in Europe are growing in strength, there is an acknowledgement that the window of opportunity to try to end the conflict and help Ukraine could be short. The date of the next American election, which could lead to a change in the US foreign policy approach if the Republicans win, is weighing heavily on the minds of the various leaders in attendance this week.

Ukraine’s Nato limbo is set to continue

As the Nato summit on international security opens this week in Vilnius, one obvious issue will be the success or otherwise of the Ukrainian counter-offensive. Apart from the liberation of a few villages, where are the victories earlier forecast by figures like head of military intelligence Kirill Budanov, who predicted the Ukrainian army would be in Crimea by the end of spring? Hopes of a quick push to the Azov sea, inspired by the retaking of Kharkhiv last September, have hit a sandbar this time round: denser Russian defence lines and widespread use of landmines. Come autumn, the weather will be against the Ukrainians too, the muddy season making a counter-offensive more and more beleaguered. Is anything for the Ukrainians going right?

Perhaps all this partly accounts for the level of resentment at the West expressed by some top Ukrainian officials. Commander-in-Chief Valery Zaluzhny has voiced frustration that Ukraine, though expected to claw back territory from the occupying Russians, still hasn’t received modern fighter jets; while regarding the possibility of Nato membership, president Zelensky has complained that: ‘If we’re not acknowledged and given a signal in Vilnius, I believe there is no point for Ukraine to be at this summit.’

Anger about the lack of fighter jets and continuing non-membership of Nato is part of a more general disillusionment in Ukraine; it’s becoming clear that Kyiv’s objectives aren’t just different from many of those in the West, but sometimes totally opposed. Ukraine needs a victory and restoration of its 1991 borders – at all costs, even escalation – while the West arguably wants merely to contain the conflict, even at the price of prolonging it.

But is there such an entity as ‘the global West’ at all? Even five hundred days after the war’s outbreak, Western countries still haven’t really united over Ukraine and its future. On the one hand, there is a clearly ‘pro-Ukrainian’ block of countries, a ‘Northern Coalition’ (numbering UK, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Poland and the Baltic States in its ranks) and putting muscle behind its words. The UK’s military aid amounts to £3.9 billion, second only to US, and both Denmark and the Netherlands are offering F-16 training for Ukrainians. Poland has contributed nearly £2 billion of aid and endless support for refugees, while the three Baltic States are donating 1 per cent of GDP to the war-effort, several times more than the average Western country. But Germany, despite its latest £2.3 billion aid package, has declared itself ready to block Nato membership for Ukraine; while Orban in Hungary claims victory against Russia is a ‘fairytale’ given that the country has nuclear weapons (clearly forgetting the US’s defeat in Vietnam and the USSR’s in Afghanistan).

The West’s divisions mean long-term support for Ukraine is far from guaranteed

As for the ‘heavyweight’ United States, a recent article in Newsweek suggests Biden’s emissary, CIA director William Burns, cooked up a deal with Putin at the end of 2021, promising that the US would neither fight directly nor seek regime change provided Russia ‘limit its assault to Ukraine and act in accordance with unstated but well-understood guidelines for secret operations’ [not crossing certain borders or attacking each other’s leadership or diplomats].

All this is far from good news for Ukraine – the West’s divisions (often not just one country from another, but within administrations too) mean long-term support is far from guaranteed. Even the widespread and apparently sincere pledges that ‘we will support Ukraine as long as it takes’ can only be honoured as long as an administration is actually in office.

All one can be sure of for now is that such support will be strictly limited, to avoid Russia’s humiliating defeat and a subsequent global escalation. The West can hardly be accused of not sticking to its promises – much has been given already and even more announced (like cluster bombs and F-16 air fighters). But while Western support has been sufficient for defence – as time has shown – it’s not enough for a game-changing offensive. As General Zaluzhny recently remarked in an interview, ‘For an offensive to accelerate I need more weapons – of every kind, and I need them now.’

Putin has now burnt enough bridges to prevent his backing off – mobilisation, meat-grinder conditions for hundreds of thousands of troops, and declaring the newly-occupied territories Russian by constitution. Given the world’s ‘grey market’ in dual-use components and Russia’s relations with China and the ‘Global South’ countries, it’s also impossible to bar its access to military technology.

Considering Russia’s population and the fact its mobilisation-potential is four times that of Ukraine, chances of its smaller neighbour winning this war of attrition are slim without regime change at the Kremlin – and ‘the Biden administration,’ writes the Washington Post, ‘is very careful not to give any suggestion’ it is seeking this in Russia. The Putin regime may yet fall due to internal pressures – as we saw with the recent Wagner mutiny. But for any such action to be successful, Russia must undergo greater destabilisation, either through economic or military collapse, neither of which is currently in sight.

Even fulfilment of the declared Ukrainian objective – liberation of all its territory internationally recognised since 1991 – may not spell the end of the war, just a relocation of front lines. This is something Kyiv understands, and it desperately wants solid guarantees of Nato membership, with its governing tenet that ‘an attack on one is an attack on all.’ Such a promise would not only be a source of hope for the Ukrainian people – it would boost the army’s morale as well.

But, in reality, the chances of such a decision being made at the Vilnius summit this week are scarce, and many Ukrainians realise it. Despite unexpected backing for its membership bid from Turkey, Ukraine – Biden has just stated – is not yet ready for accession, adding that the war there needs to end before such a thing can reasonably be considered. Even here, there are grave question-marks: as former intelligence-officer and pundit Alexey Arestovich put it, ‘Imagine the… war ends, and we are in Nato, and the next day Russian missiles strike – what (will) the West…do then? There’s no answer to that’. One could also ask what the ‘end of war’ might even mean if neither country, in aid of peace, is prepared to sacrifice territories they claim emphatically belong to them.

Probably the best Ukraine can expect from this week’s Nato summit is long-term guarantees of military support – a small group of Western allies are reported as engaged in ‘advanced’ and ‘frantic, last-minute’ negotiations to finalise a security assurance declaration, with a European diplomat quoted by the FT saying: ‘It is important to keep in mind that these are not real security guarantees, the readiness of countries to defend each other.’

Instead, he explained, they were ‘more assurances that the assistance with weapons, equipment, ammunition will continue’ – at least for the duration of the war. Such a step, if it comes off, will bring Ukraine a little more confidence in the future. Which is better, perhaps, than the country might have feared – but so much less than they could have hoped for.

Wages are up – but the Bank won’t be happy about it

The labour market continues to show signs of becoming less tight – but this won’t be fast enough for the Bank of England’s liking. The UK unemployment rate rose to 4 per cent – up 0.2 per cent on the quarter. But this relatively small change is indicative of more people moving off the economic inactivity list, which fell by 0.4 per cent between March and May: a change that the Office for National Statistics largely attributes to men in this latest update.

Meanwhile the number of job vacancies in Britain fell for the twelfth time in a row: down 85,000, but still sitting at 1,034,000. Vacancies are now significantly down from their peak of over 1.2 million, but the great worker shortage continues to fuel inflation, as the UK economy struggles to fill hundreds of thousands of jobs in the labour market, compared to before the pandemic.

But the Bank will be most worried this morning about wage data. Growth in nominal, regular pay (which excludes bonuses) rose to 7.3 per cent between March and May, which ‘equals the highest growth rate also seen last month and during the coronavirus… pandemic period for April to June 2021.’

The Bank’s governor Andrew Bailey remains convinced that the UK’s stubborn inflation rate (at 8.7 per cent on the year in April) and the rise we’re seeing in core inflation (at 7 per cent on the year) is, in part, due to what he calls ‘unsustainable’ pay rises which he believes are creating second-round effects.

There are plenty of reasons to question whether a so-called wage price spiral is actually taking place. This is nothing like the 1970s, when wage increases were keeping pace – and sometimes surpassing – headline inflation. Today, it’s not obvious these pay raises are really even boosting people’s purchasing power. In real terms, wages are still down, by 0.8 per cent for regular pay between March and May – as average wage hikes continue to sit well below the headline inflation rate. This means, despite pay hikes, workers feel worse off. But the Bank insists on pushing this narrative – even though our current inflation woes are far more likely to be the result of the hundreds of billions of pounds of money-printing that the Bank undertook during the pandemic rather than these pay increases.

Capital Economics notes that a key indicator for the Bank – the rate of month-on-month regular pay growth in the private sector – slowed somewhat, from just over 8 per cent to 7.4 per cent, which could be a sign that some heat is coming out of the economy. But CE won’t rule out another 0.5 percentage point increase to the Bank Rate come August, as it’s widely agreed that interest rates will rise again. The question is by how much.

Next week’s inflation data will help inform what the Bank might do next, as market expectation now sees rates peaking closer to 6.5 per cent. But today’s update will have emboldened the Bank to keep going. The rate rise saga is far from over.

Watch: Tory MP defends Harriet Harman

Boris Johnson might have shuffled off the parliamentary stage but there was still one last drama to play out last night. The House of Commons met to debate the ‘special report’ prepared by the Privileges Committee into the MPs who criticised their integrity when they probed the former Prime Minister. Amid the usual partisan taking points, Mr S was struck by a speech by one of the more thoughtful members of the 2019 intake, Laura Farris. With tears forming in her eyes, the Newbury MP spoke out in defence of the committee’s chairman Harriet Harman who was unanimously elected to the post in June 2022:

To contextualise the appointment of the Mother of the House, I want to say on her behalf that she had already announced her intention to retire from Parliament at the next election. Her parliamentary career has spanned five decades and has been defined, probably more so than that of any other person who has ever sat in this House, by her commitment to the advancement of women’s rights. Fourteen weeks before she took up that appointment, her husband of 40 years, Jack, had died. Against that background, I invite Members to consider what is more likely: that she agreed to chair the Committee as a final act of service to this House or that she did so because she was interested in pursuing a personal vendetta against Boris Johnson?

The appreciation of the House for this tribute was demonstrated by Penny Mordaunt’s conclusion of the debate: ‘We are at our best in this place… when turn up and step up to do what we think is right, even though there was no expectation that we would, as my honourable friend has done today.’

The police haven’t learned from the Carl Beech fiasco

It has been announced that ‘Opertion Soteria’ is to be extended from five pilot areas to every police force in the country. Operation Soteria is the name given to a supposedly new method of investigating rape and other serious sexual allegations.

A report into the results of the Soteria pilots, written by the academics who were largely responsible for devising Operation Soteria in the first place, concluded, perhaps unsurprisingly, that they had been a great success.

The Soteria approach may indeed increase the rape conviction rate, but it will do so by convicting more innocent people

In Hellenistic religions, a soteria was a ‘sacrifice or series of sacrifices performed in expectation of… deliverance from a crisis.’ The crisis from which Operation Soteria is supposed to deliver us is an epidemic of rape.

Whether there is, in fact, a particular epidemic of rape, as opposed to changes in police recording criteria and greater willingness to report it is very hard to say, but few will disagree with the overall objective of trying to convict more rapists.

The Soteria approach is based upon six principles, or as it calls them, ‘pillars’. Some of these seem on their face very sensible such as ‘identifying repeat suspects’, or ‘improving the use of digital material’ in rape investigations. Another is entitled ‘embedding procedural justice and engaging victims,’ which seems to mean that the police should treat complainants well. Apart from the implied assumption that all complainants are victims, nobody could disagree with that principle either.

However, the very first pillar of Soteria does give rise to serious concerns. Police forces will now be required to take a ‘suspect-oriented’ approach to investigations. The police, the report explains, should:

‘begin by examining the suspect’s offending behaviour early in the investigation, rather than focusing on the victim as the first and primary site of the investigation.’

The law presumes suspects innocent until their guilt is proven, but this is not the Soterian way. The suspect’s ‘offending behaviour’ is to be assumed and it must form the starting point of the police investigation.

According to Mrs Braverman, who has enthusiastically supported Soteria, this

‘… will help ensure investigations focus on the suspect, and never on seeking to undermine the account of the victim.’

Well, indeed it will, but the police should not be encouraged to begin by skewing their investigations in favour of a potential prosecution. Nor should they be deterred from looking for evidence which undermines an accusation.

Investigators should be neutral, or if that is unattainable they should at least start from a position of neutrality. The police have huge investigative powers, while suspects cannot possibly conduct the sort of investigations that might be needed to demonstrate that a complainant’s account is unreliable or dishonest. If the police are deterred from uncovering evidence of falsity, the chances are high that no one else will be able to do so.

The Soteria approach may indeed increase the conviction rate, but it will do so by sacrificing justice or, less abstractly, by convicting more innocent people.

And quite apart from this – one would have thought obvious – point of principle, the police have a duty, based on statute:

‘to investigate all reasonable lines of inquiry, whether whether these point towards or away from a suspect.’

It is difficult to see how they are supposed to reconcile that duty with the Soteria and Suella Braverman approach.