-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Has Salman Rushdie become his own pastiche?

If there were ever a Spectator competition for the best pastiche of the opening words of a Salman Rushdie novel, a pretty good entry might be: ‘On the last day of her life, when she was two hundred and forty-seven years old, the blind poet, miracle worker and prophetess Pampa Kampana completed her immense narrative poem about Bisnaga.’ By coincidence, these are also the opening words of Victory City, a book Rushdie finished not long before last summer’s stabbing.

And, as it turns out, that first sentence sets the scene for much of what follows – because the novel takes its place alongside the likes of John Updike’s Villages (about adultery in the American suburbs), Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein (a Jewish intellectual negotiates the modern world) and Martin Amis’s The Inside Story (Philip Larkin, his dad, foxy 1970s ball-breakers, etc) as one of those late works whose appeal is tinged with a kind of nostalgia. Objectively viewed, they may not add much that’s new to their author’s oeuvre. On the other hand, there’s something undeniably stirring about seeing these writers perform a selection of their greatest hits with such undiminished commitment.

In Rushdie’s case, this means that after a few novels based mainly in contemporary America, the old boy returns to India for a full-throated mix of history and magic realism, served with lashings of wildly imaginative, slightly bonkers storytelling.

For those a little rusty on their 14th-century Indian history, Bisnaga, where the book is set, was once one of the world’s grandest cities, with an empire to match. Yet, while Rushdie has clearly swotted up on this, it seems a safe bet that the place didn’t suddenly spring into existence, as it does here, when a goddess-possessed 18-year-old girl told two cowherds to scatter seeds on the ground.

After many incident-packed years, Pampa turns herself into a bird and flies back to Bisnaga

The girl in question is Pampa Kampana who, with 229 years still to go, has already had an eventful life. Following the destruction of her home kingdom of Kampili (another real place) when she was nine, she watched her mother join the other local widows in walking into a bonfire. And with that, the spirit of the goddess Parvati entered her, giving her the magical gifts that will come in handy for the rest of the novel. She then spent nine years in the cave of Vidyasagar the priest, whose vow of celibacy didn’t survive her blossoming into a beautiful teenager.

Until then, Pampa had been mute (the blindness comes much later), but she leaps into verbal action when the two cowherds, the brothers Hukka and Bukka, show up with the seeds that she grows into an instant city. Nor does her creation of Bisnaga end there. For the next nine days she secretly whispers to its newly fledged inhabitants the stories of their lives.

Before long, both Hukka and Bukka are understandably in love with Pampa, but her choice falls on Hukka, who also becomes king, with Bukka as his heir. Not that she proves a biddable wife and queen, openly continuing her pre-marriage relationship with a Portuguese traveller ‘as handsome as the daylight’. Even so, King Hukka follows her advice on practising religious tolerance and recognising female equality (or possibly superiority) in all areas of life and work, including soldiering.

As a result, Bisnaga is soon flourishing. Unfortunately, as the novel tells and shows us more than once, ‘golden ages never last’. Hukka gradually falls under the malign influence of Pampa’s old teacher and abuser Vidyasagar, who persuades him to reverse his former willingness to ‘embrace persons of all faiths as equal citizens’.

In the circumstances, Hukka’s death is well timed. Before ascending the throne – and taking his place as Pampa’s next husband – Bukka had been a cheerful drunk. Now he undergoes a Hal-like transformation into a wise and kindly ruler, with the happy consequence that ‘Hukka’s puritanical religious sensibilities were replaced by Bukka’s happy-go-lucky lack of religious rigour’.

Again, though, only for a while. When Bukka dies, Pampa’s feminism, belief in free love and embrace of diversity fall so out of fashion that she’s forced into exile with her three daughters, and they go off to live in an enchanted forest. Sure enough, once there, the novel moves into magic-realism overdrive. Pampa keeps in touch with events in Bisnaga by means of talking owls and parrots that she sends to the city to find out what’s going on. They duly report the melancholy news that the new fundamentalist Hindu king has decreed that ‘henceforth our narrative, and our narrative only, will prevail’.

Whether or not this is an allegory for Modi’s India, there’s not much doubt about what’s signified by the equally vocal pink monkeys causing trouble back in the forest. ‘They said they were, in essence, simple traders, employees of a trading company from far away,’ we’re told. The forest spirits, however, are not fooled. ‘The monkeys mean to harm us,’ they sing, ‘and to rule us if they can.’

Many incident-packed years later (summarising Rushdie plots is never an easy business), Pampa turns herself into a bird and flies back to Bisnaga. Once there, she resumes her human appearance, aged 191 but still looking as young and gorgeous as ever.

Luckily, this is another well-timed event, because ‘the greatest king in the history of the empire was about to take the throne’. Not only does Krishnadevaraya appreciate Pampa’s worth (and gorgeousness) but he also sets about making a Bisnaga ‘in which all divisions – of caste, of skin colour, of religion – would be set aside and the kingdom of love would be born’. And so another golden age begins.

There’s not much doubt about what’s signified by the vocal pink monkeys causing trouble in the forest

Until, that is… Well, by now you probably get the idea – which is the main problem with Victory City. Again, this is not unknown in Rushdie’s work, but the sense increases that, if he were less distinguished, an editor might have risked the words ‘You need to lose around 80 pages, Salman’. Admittedly one of the book’s themes is that history moves in repetitive cycles. The trouble is that fiction which does the same thing inevitably suffers from the law of diminishing returns, especially as the eras of bigotry and those of tolerance each tend to be described in much the same way. At one stage, reflecting on the downsides of living for centuries, Pampa tells herself: ‘The story of a life has a beginning, a middle and an end. But if the middle is unnaturally prolonged then the story is no longer a pleasure.’ Oddly, this is not a lesson she passes on to her creator.

Another familiar flaw comes with the limits of Rushdie’s feminism. Although he does his plucky liberal best to champion female equality (or superiority), you can’t help noticing that the ladies he particularly prizes are all stunners: not just Pampa (‘the promiscuous beauty whom neither time nor motherhood could age or tame’) but also her daughters, who go from being ‘beautiful teenage girls’ to ‘a trio of mature beauties’.

All in all, then, like those books I mentioned at the start, Victory City perhaps backs up the theory that most great writers eventually become their own pasticheurs. Yet in the end, I’d suggest, the sight of their traditional – and perhaps by now even endearing – foibles adds to the nostalgic fun.

It helps, mind you, that Rushdie’s characteristic strengths are still there too. The book has a present-day narrator who’s come across Pampa’s narrative poem and who retells it with only the occasional intervention or comment. He is, he informs us, ‘neither a scholar nor a poet but merely a spinner of yarns… who offers this version for the simple entertainment and possible edification of today’s readers’. And in all this his mission is definitely accomplished. More than 40 years after Midnight’s Children, there’s still nobody who spins a yarn quite like Salman Rushdie.

In fact, as one faintly unhinged but dazzling set-piece gives way to another here, you begin to feel that to complain (as I just have) about over-abundance or recurrent obsessions in his work is both slightly ungrateful and as wholly pointless as wishing a hurricane would tone it down a bit.

The UK is right to keep faith in crypto

It will be a charter for fraudsters. It will usher in an open-season mindset for money launderers and criminals. And it will drag down the reputation of the City. There will be plenty of critics of today’s government decision to push forward with a regulated cryptocurrency market in London. In the wake of the FTX scandal, one of the largest in corporate history, many would rather see it banned completely. But crypto is more resilient than that – and the UK, if moves quickly, it can carve out a lucrative space as its leading hub.

No one could accuse Rishi Sunak or Jeremy Hunt of taking any risks with the British economy. Nor have the Prime Minister or Chancellor shown much interest in boldly re-inventing the country’s business model. So long as the pound is not in freefall, they seem to feel they have done enough. Even so, they may finally have found at least one reform that, at the margins, shows some signs of radicalism. The Treasury today set out plans for creating a regulatory framework for trading cryptocurrencies in London. It will include plenty of oversight, along with safeguards for investors. But the important point is this: it will be relatively liberal, and a lot more welcoming than the regulations planned in the European Union – or indeed in the US.

True, it is volatile. But the same can be said of many assets. It doesn’t mean crypto is devoid of value.

Sure, the move will attract plenty of criticism. The FTX collapse has confirmed for many people that digital currencies such as Bitcoin should be outlawed completely. They are flimsy, fragile and often fraudulent. At best, they are just another vehicle for speculation. At worst, they are a cover for criminals. Creating a market for them, even if it is a regulated one, is just another example of the UK encouraging the worst excesses of financial capitalism.

Well, perhaps. And yet the mainstream critics of Bitcoin – and other cryptocurrencies – miss how resilient it is. Bitcoin has been through four major booms and busts so far and has bounced back each time. It fell heavily after FTX collapsed but, true to form, has rallied since then, and is now trading at $23,000, up almost 40 per cent since the start of the year. Anyone who assumed that it was dead when its main exchange went down has been proved wrong. True, it is volatile. But the same can be said of many assets (just look at the price of oil). It doesn’t mean crypto is devoid of value.

London can carve out a space for a properly regulated crypto market. The city has the legal framework, the global reputation and the depth of trading and financial expertise to do it properly, and to create a place where investors can feel their digital assets are safe. Other financial centres could do that as well, but right now they are too busy condemning it to see the opportunity. Sunak and Hunt may not have got many things right. But embracing cryptocurrencies and moving forward with a properly regulated market can only strengthen the City of London – and the battered UK economy as well.

Could Boris Johnson run for president? ‘I don’t rule it out’

The 2024 race for the White House is on. Donald Trump is in, Nikki Haley is getting ready, Joe Biden is preparing to fend off intra-party foes – and now, Steerpike has learned of another possible entrant: former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

One of Steerpike’s Spectator colleagues in America caught up with the ex-PM at the Capitol Hill Club in Washington, DC. When asked if he wanted to move from 10 Downing Street to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Johnson told the Cockburn gossip column: ‘I don’t rule it out.’

Johnson, who is visiting the US to push for additional aid to Ukraine, did not specify whether he would run as a Republican or Democrat. He did bump into Cockburn at a famous Republican haunt, but the cause he’s championing is one supported by members of both parties.

Before leaving Downing Street last September, Johnson was a staunch supporter of Ukraine. He visited Kyiv in the opening months of the war, and Britain provided about £2 billion of aid under his leadership. Ukrainians, in their gratitude, have named everything from cakes to streets after him. He has even been awarded Ukraine’s Order of Liberty – the highest honour the country provides to foreigners.

It remains to be seen how possible – or serious – Johnson’s presidential aspirations are. The former Spectator editor renounced his American citizenship in 2016, in part to ‘ensure he is out of reach of America’s Internal Revenue Service,’ the Guardian reported. He was, however, born in New York City and so might be able to reapply.

While Johnson was forced out of the prime ministership with low approval ratings following a series of coronavirus-related scandals, it’s possible that he would find a more favourable climate in America, a famously Anglophilic country. After all, America’s current president was just bullied into declaring that the coronavirus is over.

Certainly, Johnson did little to dispel the notion that he’s still plotting a comeback, at the expense of his successor-but-one Rishi Sunak. His appearance on Fox News was notably unhelpful for Sunak, as he condemned his decision not to send fighter jets to Ukraine. Johnson suggested it would ‘save time’ if the UK and its allies gave Zelenskyy’s forces Typhoons and F-35s, declaring that:

I remember it being told it would be the wrong idea to give them the anti-tank missiles. Actually, they were indispensable. Same with tanks.

The US is becoming a place where former Tory prime ministers can attempt to reboot their political careers. Liz Truss cavorted with House Republicans last month – as Johnson plans to do – to figure out how to organise elected British conservatives.

Announcing his resignation, Johnson said that ‘like Cincinnatus, I am returning to my plow.’ At the time, this was interpreted in Britain as Boris floating the possibility that he might one day come back to frontline politics, if duty called. The reference was rather vague – who’s to say he didn’t have this side of the pond in mind?

Why are the Tories dragging their feet over public sector pay?

Why haven’t ministers sent their submissions to the independent pay review bodies for their sectors? That’s the question being asked of Education Secretary Gillian Keegan and Health Secretary Steve Barclay, both of whose departments have missed their deadlines for submissions on next year’s pay settlement.

Some hope that a more generous pay settlement for next year might make it harder for trade unions to continue striking

Keegan was out and about on the airwaves dealing with the start of the teaching strikes this morning, and explained that the education department had ‘halted’ the submission on future pay. She told the Today programme:

‘We want to keep open those discussions about future pay and I didn’t want to set something while we could still have constructive discussions.’

Barclay was asked a similar question when he appeared before the Health and Social Care Select Committee yesterday. He offered a little more detail, saying:

‘Once we completed ours, some time ago, there’s been a need to wait for other departments to also have those discussions. That is, across government, a process co-ordinated by the Treasury. And once the Treasury is happy for the department to submit this, we are ready to do so.’

Some in Whitehall hope that a more generous pay settlement for the next year might make it harder for trade unions to continue a programme of strikes. If voters see that workers are getting more money for the next year they will wonder why there are still picket lines.

The current walkouts are about the pay settlement for 2022/23, and there is widespread public support for nurses and teachers in particular, with most voters blaming the government for the disruption rather than the unions.

In both sectors, the disputes have been coupled very effectively to the state of the public services the union members work in. The public can see how much of a crisis the NHS is in every day, not just during strikes, and while parents don’t want their children to miss even more lessons after a good few years of Covid disruption, they can also see how much their schools are struggling financially at the moment. But some Tories are hopeful that if the Treasury agrees to submissions from departments recommending a pay rise that is at least closer to inflation, then they can start to undermine the public support.

The current Treasury position on the 2023/24 pay offer is that pay should not rise by more than 3.5 per cent in order to keep a lid on inflation. There are still concerns within both health and education that any raise would have to come out of existing budgets and would therefore impact still further on the limited resources staff have to work with. Even when the submissions are in, this is going to be an extremely difficult battle for ministers – and likely an unpopular one too.

What the Tories can learn from Cato the Elder

One MP pays a tax fine, one borrows money from a relation and one is accused of bullying staff. More ‘corruption and sleaze’? Romans might have seen it as a matter of basic values.

In 443 bc, Rome established the prestigious office of censor, to be held by two men, usually ex-consuls. As well as maintaining an official list of Roman citizens and their property (the census), they were also responsible for the oversight of public morals (regimen morum).

Anyone who fell below what the censors regarded as the high standards of a Roman citizen was removed from his tribe, was not allowed to vote and had a mark made against his name on the citizen register.

The most famous censor was Marcus Porcius (‘Carthage must be destroyed’), also known as Cato the Elder (234-149 bc), ‘a man to whom severity was ascribed for the whole of his life’. Surviving extracts from his speeches give a sense of the man: ‘I have no expensive buildings, vases or clothes, no costly slaves. If I have anything to use, I use it; if not, I do without… what one does not need, however cheap, costs too much.’

For Cato, indulgence in luxuries, especially clothes, vehicles and extravagant feasting, led to avarice, corruption and love of the ‘soft life’ (he condemned the erection of statues to two cooks with the words ‘obsession with food, none with virtue’). Under his watch, seven senators were expelled, cavalrymen were downgraded for lack of fitness, and others were too, for letting their farms run to waste.

He was equally strict in the other area of the censor’s work, public contracts. Personal gain from public office, including the private distribution of booty, was anathema to him and he saw to it that as much revenue as possible went to the state and that public works were leased without excessive profits for the contractors.

‘The benefit of the republic’, a constant refrain in his speeches, was what counted for him.

Later generations heroised this dictatorial family man, who made the same severe demands on himself as he did on others. Do such politicians still exist?

In praise of greyhound racing

I feel strangely and disproportionately elated when Number 2 dog, Ballyblack Bess, powers home strongly to win the 20.03 race. It’s a Monday evening in January in the greyhound stadium in Blackbird Leys, Oxford. I only won £9 but I’m pleased I came because an evening at the dogs is still great old-fashioned fun. The punters love it, as do the dogs, so it’s devastating that the RSPCA has demanded it be banned. They’ve teamed up with two other leading charities, the Dogs Trust and the Blue Cross, to request that it’s phased out over a five-year period.

But the RSPCA is – excuse the pun – barking up the wrong tree. The main objection to the sport was always about what happened to the dogs once their racing careers were over. But in 2020 a new Greyhound Retirement Scheme was introduced by the sport’s governing body, the Greyhound Board of Great Britain, whereby owners and the Board contribute £200 each to a bond which assists with homing costs. Contrary to the claims, there is a life after racing for these magnificent athletes and most of them are well looked after. In Oxford, retired greyhounds, looking very handsome in their smart jackets, are taken round the bars and restaurants to meet the public.

Another complaint was about racetrack safety. But national track fatalities have, according to industry figures, halved between 2018 and 2021 (from 0.06 per cent to 0.03 per cent). I’ve been racing five times since September and, having seen the best part of 50 races and 300-odd dogs competing, I can recall seeing only one greyhound limping after a race. Even when there are injuries, vets are always in attendance.

If the abolitionists do get their way, an important part of our sporting and cultural heritage will be lost. In its heyday in the mid-20th century, greyhound racing was second only to football in popularity, followed by the upper and working classes alike. In the immediate postwar era attendances were roughly 70 million a year. There were more than 200 licensed dog tracks in Britain and 25 in London alone. ‘Going to the dogs’ for an evening of exciting action and a slap-up meal was the night out.

Some would say greyhound racing is now a niche pastime, with no terrestrial TV coverage, but it’s a credit to the dogs that despite everything it remains the country’s sixth most popular sport. One of its major advantages is that you can stand right up close to the action, as you used to do in football stadiums before all-seaters took over. No matter how many races I see, I always marvel at the speed of the dogs as the traps open and they tear after the electric hare. The dogs love racing; it is what they are bred to do, and those who call the sport ‘cruel’ really ought to attend a few meetings.

None of this does much to silence the critics. The situation in Wales and Scotland is particularly worrying. In the Principality there is only one remaining track, the Valley Stadium in Ystrad Mynach, and in December the Senedd’s petition committee called for the sport’s gradual abolition. In Scotland it received a three-month reprieve in November, pending the completion of a report of the Scottish Animal Welfare Commission, but the only licensed venue, Shawfield in South Lanarkshire, remains closed after the 2020 lockdown and is in a sorry, dilapidated state.

It’s easy for activists to insist that greyhound racing’s days are numbered, but what happened in Oxford is instructive. The stadium shut down in 2012 after 73 years and the site was earmarked for housing. Promoter and enthusiast Kevin Boothby wanted to bring the greyhounds back, but was met with a vociferous campaign to stop their return. The deputy leader of the Green party group on Oxford City Council joined up with the Lib Dems and branded dog racing ‘a barbaric practice’. Actress Miriam Margolyes, who was brought up in Oxford, weighed in, writing a letter to the council that described racing as a ‘ghastly business’. A petition from the animal rights group Peta attracted more than 32,000 signatures.

Everyone assumed the council would buckle under the pressure. But the greyhound track did reopen for business in September, and on the opening night the small number of protestors were greatly outnumbered by the 2,000 or so spectators who all had a wonderful time.

Many tracks have been lost in recent years but Greater London still has Romford, and Birmingham has Perry Barr, both historic venues dating back to 1929. If the sport is to survive, we need to get out there on cold winter evenings to support it.

I know where the Met police are going wrong

I have a puzzle for the Metropolitan police – a mystery that only they can solve. Why, if the Met is so short-staffed, do they hang around in groups? Why do officers clump?

Why are some crimes completely ignored, but at other minor incidents the Met appear en masse? In London side streets I come across police vans, bumper to bumper, full of officers just sitting, doing nothing, like large unhappy children on a school trip. It’s demoralising for me. I can’t imagine how depressing it must be for them.

If you’re in the business of finding decent, non-rapey officers, it’s clearly a good idea to look them in the eye

Sir Mark Rowley, the new Met Commissioner, has announced what he calls the ‘Turnaround Plan’ for transforming the Met. The first step is a ‘listening’ exercise so as to ‘rebuild the trust and confidence of Londoners’. As a Londoner, I should have ‘a greater say in determining my policing needs’, Sir Mark says, which suits me just fine. I have a long list of policing needs.

First up, I’d like the men of the Met to have a shave. Every single one of them has some sort of beard and it makes them look shifty. This is not a strong look, considering. My second policing need is for the Met to do away with virtual recruiting. During Covid they began to interview prospective officers online, not face to face, and they’ve never phased it out. But if you’re in the business of finding decent, non-rapey officers, it’s clearly a good idea to look them in the eye. Online dating tells you all you need to know about that.

The third and most pressing policing need I have is to clear up this question of how and why officers are deployed. I’m a full-time observer of the Met. I bike round town every day and I’m drawn to the flicker of blue lights like a sort of rubber-necking vampire moth. And what perplexes me most is not the shortage of cops so much as the wasting of their time.

Why, for instance, were there 30 or so uniformed police officers protecting the Home Office from four amiable-looking animal rights activists on Monday last week? There was a man with a wheelie bag and three ladies holding placards with photographs of beagles on them. That was it. Because of all the cops, I assumed a ruck was in the offing, and that a great wave of animal activists was about to descend to liberate the Home Office beagles. So I bought a coffee and sat down to see what happened.

No one else appeared. Sometimes the women shouted ‘science is violence’ but mostly they discussed whose coat was best for outdoor activism. Four Met officers in pale blue – liaison officers – had a stab at joining in the coat banter but even from a distance it looked awkward. At about 4 p.m. there was a general agreement that a red-haired lady in a lined parka had the most suitable coat, and after that the protestors peeled off, leaving a line of embarrassed-looking cops stretching from one end of Marsham Street to the other, protecting their own HQ from nothing.

As I left I passed a senior detective, and remembering my ‘greater say’ I had a polite word: why six officers for every activist? He looked cross. ‘We can’t tell how many will turn up,’ he said, then turned his back on me. I don’t think he was up to speed on Sir Mark’s listening mission. Nor was he open to my other questions like: ‘Why can’t you tell how many protestors will turn up? Don’t you check their Facebook page? And now the activists have gone, why are all the officers still standing here?’

If he’d read the Turnaround Plan, and known he should be open to civilian ideas, I might have suggested that he redeploy every officer instantly to stand outside school gates. It was going-home time for pupils, and all over London, after school, pupils are being mugged at knife-point for their phones. On Friday, the headmistress of St Mary Magdalene, Islington, round the corner from me, published a desperate open letter begging the council for help: ‘Following the mugging of yet another pupil yesterday at approximately 4.30 p.m., this one at knife-point and the pupil requiring medical attention, I would urge those of you with the ability to do something about street safety and street crime in the area to do so… the school has no power to bring change in this situation other than continuing to shout with an ever louder, more urgent voice.’ Perhaps liaison officers could be sent in to josh with the hoodies?

A few weeks ago, on my way to the Imperial War Museum, I saw a bus stop full of what looked like dead men, slumped, too still to just be drunk. There were three of them, and the youngest, 18 or so, had yellow skin and his eyes were slightly open. Passers-by stared, but didn’t stop. I guess it’s hard to deal with a pile of corpses at 11 a.m. when you’re desperate for the 344 to Clapham Junction. When I looked closer, two of the men were definitely breathing but I wasn’t sure about the yellow boy, so I called 999 and explained, and then went to try to shake him awake.

When the first set of policemen arrived – four officers in a panda car – I was relieved. I hadn’t managed to wake the boy, so one of the cops took over the shaking and he began to stir. Then another three cops arrived, a medical car and an ambulance. Within about 20 minutes the bus stop looked like a sort of first-responder social event. There was only room at the bus stop for two, so the rest of us stood around and discussed the nature of the overdose. ‘Smack, maybe meth? Fentanyl? Yeah.’

I think the men were OK and I hope the boy recovered, but why were seven officers sent to deal with one comatose addict? I left with the sense that there’s something very wrong, not just with the odd rogue officer, but with the whole management of the Met.

America’s colour blindness

How many black cops does it take to commit a racist hate crime? The latest correct answer is ‘five’. That’s the number of policemen in Memphis who have been fired and charged with second-degree murder for the killing of Tyre Nichols.

Last month Nichols, who was himself black, was pulled over by the officers. They proceeded to kick him, pepper-spray him, hit him and repeatedly baton him. He died in hospital three days later.

Of course, if the Memphis officers had been white, American cities would be being burned and smashed to the ground again, as they were three years ago after the death of George Floyd. On that occasion it was asserted that Floyd was killed because he was black – something which, interestingly, wasn’t claimed at the white arresting officers’ subsequent trial and conviction. But if you see everything through the lens of race, that is what you do. Rogue white cop kills black male? Must be racism. How then to deal with the profiles of the officers charged in this latest case?

Easy! You simply assert that five black officers killing a black man is further evidence of white supremacy. ‘Huh?’ you may well ask. Here to explain is CNN’s Van Jones: ‘The police who killed Tyre Nichols were black. But they might still have been driven by racism.’ And how does that work? According to Jones, ideas of black inferiority are so ‘pervasive’ that ‘black minds as well as white’ can fall prey to this racism. ‘Self-hatred is a real thing,’ he said. I don’t know if the same applies to the dozen or so black folks shot by other black folks on an average weekend in Chicago. If that’s all a result of white supremacy then there’s an awful lot of it going around – mostly unnoted.

But when it comes to a black person killed by the police these days, the US goes into a set routine, whatever the facts. After footage of the Nichols arrest was released, President Biden said he was ‘outraged and deeply pained’ by the video. So far so natural. He then added: ‘It is yet another painful reminder of the profound fear and trauma, the pain, and the exhaustion that black and brown Americans experience every single day.’

The President who was meant to heal America has once more shown his brilliance at dividing it. Even his language there is borrowed from the latest generation of American race-hucksters. Whenever racism is brought up by today’s activists, they say that they are ‘tired’ and ‘exhausted’ by it, as though rather than getting a liberal arts degree and spending their days online they are at the forefront of the most gruelling civil rights campaign.

We were also reminded how easy it is for us in Britain to end up as a mere satellite of this particular American culture war. For days on end our news led with the story of the Nichols killing, as if it had happened in Manchester, not Memphis. Breaking news around his death took priority over all that was going on at home.

This is the way now. While the BBC and other UK media pore over every racial aspect of a US killing, they say almost nothing about French police again beating the hell out of protestors during a recent march against pension reform. One of those young protestors had a testicle amputated after he was batoned where it hurts. Likewise, when French police shot two dead on the Pont-Neuf in April last year, it didn’t dominate the British news for several days. That’s because with those stories there isn’t the simplistic ‘wish-it-was-the-civil-rights-era’ racial lens that is put on everything coming out of America.

Our very own David Lammy spotted the opportunity, as he often does. This may be a man who infamously believed Henry VIII was succeeded by Henry VII, but history isn’t the only thing the shadow foreign secretary has back to front. Last weekend he sent out a statement on Nichols’s death saying: ‘It’s traumatic, exhausting and tragic to watch footage of yet another black man killed by those whose duty it is to protect. Tyre Nichols should be at home with his family today. Justice must be served. Police violence against minorities must finally end.’

As it happens, black people are not a minority in Memphis. They are, in fact, a majority (64 per cent). More importantly, Lammy didn’t bother to inform his followers that on this occasion his ‘exhaustion’ comes from watching footage of five black men killing another black man. Doubtless that would run counter to his favourite American-adopted narrative.

The same narrative was followed by a guest on Sky News. In Britain and America, ‘good’ police are ‘the exception not the norm’, the activist Shola Mos-Shogbamimu told viewers. ‘The source of this problem is white supremacy.’ Kay Burley tried to quietly mumble that the arresting officers were black. ‘I’m about to educate some people right now,’ replied Shola, with characteristic humility. ‘White supremacy underpins the policing and criminal justice system both in the United States and United Kingdom.’ This is apparently done through a combination of white supremacist police officers and ‘black and brown’ gatekeepers who are white supremacists too. Gosh.

How is any of this to change? Well, as one final expert on policing, Whoopi Goldberg, suggested on one of America’s most influential TV programmes, The View: ‘Do we need to see white people also get beaten before anybody will do anything?’ As it happens Ms Goldberg, Van Jones, Shola Mos-Shogbamimu, David Lammy and anyone else who wishes can go online and see white people being beaten by US cops from an array of racial backgrounds. They can also watch the snuff movie of police in Dallas killing the (white) Tony Timpa – for which no officer was ever charged. We could all get exhausted. But it’s only this reductive, race-obsessed narrative that actually is.

Japan’s plans for an anti-China alliance

As the world’s attention focused last month on whether to send tanks to Ukraine, Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, was on a whistle-stop tour of the West. He held various meetings with G7 leaders, including Rishi Sunak and Joe Biden. His objective was clear: to create a new alliance that can counter China.

Japan has been forming a ‘Quad’ with Australia, India and the US on naval manoeuvres

Japan adopted a ‘peace constitution’ in 1947 when it was occupied by the US, pledging that the country would never again wage war. For the past half a century, the military budget was capped at 1 per cent of GDP, and Japan sought to project its image abroad as a semi-disarmed economic giant, an Asian Germany of sorts.

Now all this has changed. Kishida is increasing Japan’s defence spending over the next five years by nearly 60 per cent and acquiring weapons it has long avoided, such as ‘counterstrike’ missiles, long-range precision weapons and American Tomahawks. There are plans for more joint exercises with US forces in the Pacific, and Tokyo is investing heavily in its cyber-capabilities.

Kishida described this new alliance as a ‘turning point’. That was an understatement. Japan is making its military priorities clear for the first time since the end of the second world war, and is seeking to reshape Asia’s economy at a time when America’s economic clout in the region is giving way to China’s.

Kishida’s meeting with Biden was part of a wider US pushback against China. Lieutenant General James Bierman, commanding general of the Third Marine Expeditionary Force and of Marine Forces Japan, recently told the Financial Times: ‘We [America] are setting the theatre in Japan, in the Philippines, in other locations.’ That theatre, he implies, is one where the performance might be a US-China conflict.

Japan’s decision to become part of the theatre in question is inseparable from the issue of Taiwan. This week, a leaked memo outlined in stark terms American fears of a Chinese invasion. General Mike Minihan, who heads the US Air Mobility Command, wrote in the private briefing: ‘I hope I am wrong. My gut tells me we will fight in 2025.’ He reasoned that Taiwan’s next presidential elections are in 2024, as are the US’s, potentially creating a ‘distracted America’, which would benefit the Chinese president. ‘Xi’s team, reason and opportunity are all aligned for 2025,’ he concluded. Beijing, which hosts US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Sunday and Monday, warned that General Minihan’s comments were ‘reckless’.

To counter China’s claims over the East and South China Seas, Japan has been forming a ‘Quad’ with Australia, India and the US on naval manoeuvres. Meanwhile, America’s marine deployments on Japan’s south-western islands, near the Taiwan Strait, are being upgraded. Last week, the US Marine Corps opened Camp Blaz, its first new base in 70 years, on the Pacific island of Guam. It will have 5,000 marines and is partially funded by Japan. The US is also pushing the Philippines to allow it access to four military bases in the Asia Pacific. In return, the US has offered Manila military equipment, including drones, giving Filipino forces the ability to monitor activity in the South China Sea.

It’s easy to see why Kishida believes Japan should be prepared to join America in any contingency plans for a Chinese attack on Taiwan. An invasion could easily drag Japan into a conflict that would directly threaten its security and Tokyo knows how bloody a confrontation with China could be. A recent wargame run by Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies thinktank suggested a Chinese invasion of Taiwan in the mid-2020s might fail, but only at a very significant cost in American, Japanese and Taiwanese lives, as well as money.

Besides Taiwan, there is another maritime dispute that Japan fears could flare up this year: the Senkaku islands. Japan controls these uninhabited strips in the middle of the East China Sea. Yet China refers to the islands as the Diaoyu and refuses to acknowledge Japan’s control, instead making a rival historical claim. For decades, the Chinese have argued that they have authority from the Cairo Declaration made in 1943, which stated that after Japan’s defeat certain (unspecified) Japanese imperial island territories would be restored to China. This November marks the declaration’s 80th anniversary, and China could mark it with naval drills near the islands.

One problem with the new Japanese-western alliance is that the sides are not on the same page about every authoritarian state. There are only two countries which Tokyo perceives as an existential threat: China and North Korea. Russia doesn’t feature high on the list – whereas for Europeans it is the major adversary (although Kishida recently indicated he was willing to visit Ukraine, possibly as a nod to his European allies).

A further complication is that Japanese business continues to be a major investor in China. While Japanese companies are slowly moving some of their factories out of the country, the internal Chinese market itself is still a large prize. In 2021, Japan invested more than $8 billion there.

There is understandable scepticism, too, over whether its new defence strategy fully adds up. The government was already beset by a heavy national debt before the decision to increase the defence budget. ‘It’s a recipe for waste and inefficient allocation of resources,’ says Jeff Kingston, professor of history at Temple University in Tokyo. Japanese politicians, he argues, have ‘submitted a poorly thought-out Christmas wish list that leaves defence analysts puzzled’.

Domestic issues could also threaten Japan’s plans. The country is getting old. The economic boom ended in the early 1990s, and it has been suffering a demographic crisis for longer than that; a quarter of its population is now aged over 65. Younger people are increasingly reluctant to get married and have children. Kishida has even warned that his country is on the brink of not being able to function because of the declining birth rate. People across all age groups are wary of China, but Japan doesn’t yet give the impression of a society gearing up for a full-blown conflict.

Kishida’s ambition to turn Japan into a military power to take on the People’s Liberation Army might be real. Yet his plans will have to take into account demographic and geopolitical constraints that will not be easily overcome.

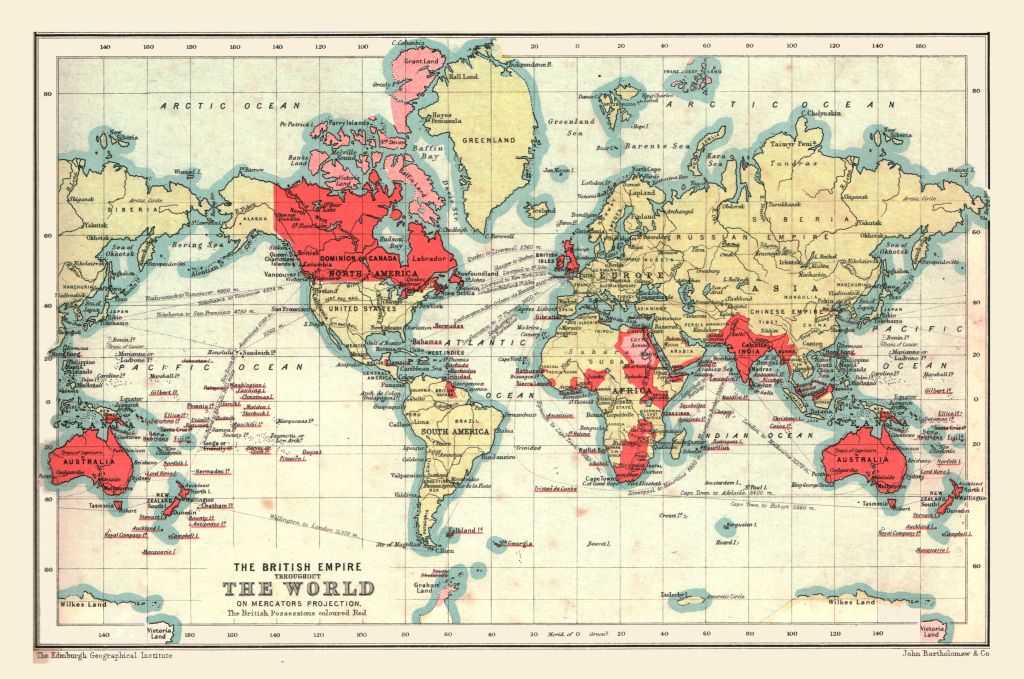

The truth about the British Empire: Nigel Biggar and Matthew Parris in conversation

Nigel Biggar is a theologian, ethicist and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning. He speaks to The Spectator’s columnist Matthew Parris about the legacy of the British Empire.

MATTHEW PARRIS: Nigel, you’ve been in the news recently over your view on colonialism, which is, I think, basically that British colonialism is not all bad. Is that right?

NIGEL BIGGAR: Yes, I’ve become a bit more assertive in my view, since I first got into trouble five years ago. I published an article in the Times saying that we British can find cause for pride and shame in our past. I thought, who on earth can disagree with that? I actually thought it was rather an anodyne point of view, but that was enough to get me in trouble. Since then, I’m a bit more robust. Certainly the British Empire does not live down to its currently prevalent caricature as being a litany of slavery and racism and exploitation. There was nothing in the empire that approximated to Nazism. But more than that, it was from the early 1800s onwards increasingly humanitarian and dominated by liberal motives. So I become more positive: not just ‘it wasn’t all bad’.

MP: I’m a child of empire. I was born in South Africa when it was still a dominion. I was raised partly in Cyprus when it was still a colony. We were fighting Greek Cypriot terrorists then. And then I went on to spend all my boyhood and youth in what was then Rhodesia and I was sent to a multi-racial school in Swaziland. The whole experience leaves me quite torn. I see your argument. I see many good things that empire did achieve. All the places where I lived as a boy have gone from bad to worse since leaving the empire. But I also have direct experience of our attitudes as colonialists. When I went to school in Rhodesia, I saw at first hand the attitudes of white settlers in that part of Africa, and they were horrible. Their attitude towards Africans was that they were not, in their view, entirely human, or at least were human beings entitled to far less than we were. I saw Ian Smith and the white settlers, and I grew to dislike very intensely the attitudes towards people of colour that colonialism had imbued all us colonialists with. At the same time, I can see there were many good things that were done. But I just ask you to reflect on the way white people, in the countries Britain has ruled, saw the people that they ruled – the attitudes that they had.

‘The Empire was from the 1800s on increasingly humanitarian and dominated by liberal motives’

NB: Matthew, you’re quite right. I’ve read a number of novels by people who lived in East Africa: Elspeth Huxley, Gerald Hanley. In the novels, these are white people bringing their own experience into these stories they’ve created, but they themselves portray what I feel to be disgusting. Yes, contempt, disdain, sometimes just a brutally rude attitude of some whites to the blacks. So what do I do with that? Well, I mean, the first thing I do is just to put this in context and to say that I do find that disgusting. But racial prejudice was not the preserve of whites. For example, Gerald Hanley, who was actually Irish-born, ended up in British uniform in Somaliland in the 1940s and he recounts the difficulty he had trying to persuade Somali troops in British uniform to accept a Bantu African as an NCO because the Somalis regarded the Bantu as a natural slave. That is just to say that racial prejudice is a pretty universal human phenomenon. I’d also say the disgusting racial contempt that you experienced and I’ve read about was common among settlers, not so common among missionaries, and less common among colonial officials. Then there is also a contrast between back home and the empire. When Gandhi came to England, he, according to his own witness, encountered nothing but kindness. In South Africa, in Durban, he was chucked out of the first-class carriage. And then last year I read the obituary of Desmond Tutu…

MP: I was at school with his son.

NB: Well, the obituary says it was when Tutu came to London that he first experienced what it was like to be in a non-racist society because the policemen were polite. He didn’t have to stand in a separate queue or be the last in the queue. I don’t want to diminish your point at all about racism; I just think it was more complex and more varied than we think.

MP: We’re both right about those attitudes, incidentally. Complete side point: the Scots were the worst.

NB: You’re speaking to a Scot. Thank you for that.

MP: The Scots in Africa were more racist. It’s interesting why this should be thought of as a shame on the English in particular.

NB: I’m glad you said that, actually, because one of the reasons I wrote this book stems from the Scottish independence referendum in 2014. As an Anglo-Scot – Scottish father, English mother born in Scotland, educated both sides of the border – I’m viscerally anti-independence. I noticed that for some Scots independence is a kind of cathartic cleansing of Scotland from the evils of Britain, which equals empire, which equals wickedness. And whatever the reasons for Scottish independence might be, that one is a false one because the empire wasn’t simply evil and Scots were deeply involved in it, for better and for worse.

*****

MP: I’ve noticed in your writing a particular emphasis on questions of human rights, of politics, constitutional questions, the rule of law and all those things where I think you’re on very strong ground. I think you’re on less strong ground on the economic case. It is quite true, when my family were in Rhodesia for instance, that at the behest of our British masters back in London, there was a good African education system. We administered the country well, though we had taken the best land for white farmers and pushed the Africans on to the not so good land. But we took our responsibilities as a colonial administrative power seriously. And I think our administrators were like their counterparts in Britain: good civil servants. But in the meantime, we were, as it were, raping the country for its economic resources: the profits that went to the big tobacco companies where the Africans laboured on the farms and the profits that went from diamond mining and gold mining. All these natural resources were being extracted and sent away from the peoples who occupied the land and into the pockets of imperial commercial organisations. Now, think of the Chinese. We know that the Chinese are, as they would put it, ‘investing’ in Africa. They are probably bribing politicians. They are probably strong-arming politicians. They’re not particularly popular with the African people and they are leaching Africa of its natural resources. We don’t approve of that. Now instead see us British as the 19th-century equivalent of the Chinese.

‘I accept that particularly in southern Africa whites took the best land and blacks were relegated to poor land’

NB: On the issue of land, I accept that particularly in southern Africa whites took the best land and blacks were often relegated to poor land. Lest anyone think that was always the case, it wasn’t. There were different stories in North America and Australia. But let’s stick with South Africa for the moment. I can see that in terms of the extraction of profit. I’m willing to be persuaded about that. I’m a capitalist and I do expect that companies should retain some profit for the sake of reinvestment, etc. I think there is a problem where the profits are not to some extent reinvested in the country and the people that do the work. I’m certainly willing to accept there were cases of that. I’m not an economist, so I have to rely on what I’ve read. I took advice from the imperial historian John Darwin, from the development economist Paul Collier and from the historian of colonial economics Tirthankar Roy. I said: ‘Well, what’s an authoritative book to read about colonial economics?’ and they recommended David Fieldhouse. Fieldhouse, first of all, says that the Marxist or the neo-Marxist view that colonial economics were raping and exploiting and draining of resources in general doesn’t stand up well against data, generally speaking. He quotes a Swiss economist, Rudolf von Albertini, who’s done the most comprehensive survey of data. He concludes that it is not generally appropriate to think of colonial economics in terms of plunder. So moving from Africa to India, I would say that the empire’s commitment to free trade, which reigned roughly from the 1840s to 1919, meant that, yes, manufactured cloth from England could out-compete artisanal cloth in India, and that caused some decline in cottage industries there. On the other hand, it meant that industrialists like Tata could come to Manchester, observe manufacturing processes, take back expertise to India and build cotton and steel factories that then competed with Manchester.

MP: It’s a side story and one that’s seldom told that there was always irritation in Whitehall and Westminster that the profits were going to companies, in many cases international companies like De Beers, and that the cost of administering our colonies was being borne by the British taxpayer. That’s why Cecil Rhodes was never very popular in London. I was educated in then Southern Rhodesia to see Rhodes as a fairly unambiguously heroic figure. On the other hand, he was not all that popular back at home in London. And people have said that Britain’s gradual occupation of large parts of southern Africa happened in a ‘fit of absence of mind’. It wasn’t really led by any kind of moral or civilising mission, but often led by British opportunists and the government following behind. Then there’s the Marxist view, which was that empire was just a particularly clever weapon of international capitalism. What’s your view?

NB: The Marxist conspiracy theory just doesn’t fit the data. My view is that there was an absence of a single mind. There were many minds so the motives for empire were multiple. Trade was a basic one. What’s wrong with that? Then you’ve got, in terms of migration to New England, religious refugees. You’ve also got people from Scotland and Ireland fleeing famine. Then you’ve got war and strategic considerations. A lot of bits of the empire like Cape Colony fell into Britain’s lap at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, or there-abouts. And then in the 19th century, you do have a genuine humanitarian idealism and mission, whether it’s abolishing slavery or human sacrifice. And then, yes, you’ve got greed and you’ve got the sheer love of lording it over the other people.

MP: If I could just interrupt, though, for a moment. Marxism does not require a single presiding intellect to blame. Marxism says that where there is money, plunder to be gained, people will go for it. That’s all Marxism says.

NB: OK, so plenty of people want to make money. I have no objection to that as such, although in some cases, Rhodes included, some people make money without many scruples. There’s certainly that, but there was also a lot more: that wasn’t the only motive and it’s not true that colonial government was always in hock to capitalists. Often colonial government tried to protect native industries against foreign investors and companies. So the Marxists are right with regard to one set of motives, but they’re not right to think that was the whole central driving story. Just on Rhodes: I should just say, although I’ve defended Rhodes so that his statue may remain standing in Oxford, if I’m going to raise a statue to the empire, it wouldn’t be Rhodes, because he was a very morally ambiguous character. The only reason I’ve defended the statue remaining standing is that so much has been projected on to him about the evils of empire. If it were to fall, it would mean the triumph of a very distorted view of history.

*****

MP: Have you been surprised, Nigel, at the ferocity, the dislike that has descended on you for expressing what appear to you to be fairly moderate opinions?

NB: Astonished. I’m naturally quite a cautious person. I think carefully. I’m not of the extreme right as I’m now being painted. Contrary to what one young Irish academic is reported to have said, I’m not funded by Breitbart. What most of all astonished me to begin with was that when I began to write about the British Empire, colleagues in Oxford or elsewhere didn’t invite any kind of conversation. What they did was to respond with abuse and aggression. I’m thinking particularly of Priyamvada Gopal in Cambridge, and I put this on record because I have the screenshot of the tweet, her response right at the beginning. She began the process that led to three online denunciations in the space of a week. In December 2017, she tweeted: ‘OMG, oh my God, this is serious shit. WE MUST SHUT THIS DOWN.’ The immediate reaction on her part was a kind of hysterical repression. And in my experience since? I’ve had very little, as it were, rational pushback. I have had a lot of abuse. There was an article published by Richard Drayton in 2019 in a book called Embers of Empire in Brexit Britain, in which I was, rather flatteringly in a certain sense, presented as a kind of icon into the meaning of Brexit. Because Brexit, as we know, is all about ‘imperial nostalgia’. But it was a concatenation of misrepresentation and slurs and misunderstanding from an academic who ought to be trained to treat what other people say carefully. I lost the co-operation of one of the most eminent historians of empire, John Darwin, with whom I had co-conceived a research project, Ethics and Empire. Four days after the first of three online denunciations were published in December 2017, he abruptly resigned for personal reasons.

MP: You think he took fright?

‘I have had to meet junior research fellows in Oxford in secret because they didn’t want to be seen with me’

NB: I’m certain he took fright, yes. And it puzzled me that a senior secure academic should be so easily scared off. There’s a lot of fear among academics that I’ve seen among my own colleagues in Oxford, particularly if they’re junior – fear for their careers. I’ve had to meet junior research fellows in Oxford in secret because they didn’t want to be seen in public with me. Some people fear with more or less reason that their careers would be punished if they even associated with people with ‘extreme’ views like mine. I find that shocking.

MP: And there was a serious attempt to bury your book. You lost your first publisher, didn’t you?

NB: That’s correct. I was commissioned by Bloomsbury to write a book on colonialism. I delivered the manuscript at the end of 2020. My commissioning editor said it was one of the most important books he’d come across in some time. It went into copy editing, produced a cover. In March, Bloomsbury cancelled it. I was devastated at the prospect that my book would not get published. I was also just dismayed because I thought to myself: ‘If every publisher in Britain behaved that way, freedom of speech in this country would be severely damaged.’ And I know publishers have commercial necessities, but surely publishers also have civic duties.

MP: Yeah, but this won’t have been that they worried about the commercial prospects of the book – had it become very controversial, it would probably have sold more copies. It will have been pressure from other employees, won’t it, within the publisher?

NB: You’re right. My commissioning editor was not responsible for this mess. Word has it that it was junior colleagues who protested. But, here again, I don’t understand – it’s the same in universities when students protest about some speaker being allowed to speak or students start to accuse Neil Thin at Edinburgh of racism just because he wanted David Hume’s name to stay on the ugly tower there. I don’t understand why grown-up university leaders are so easily manipulated by pressure from below. I don’t quite understand what the costs of resistance would be, but they don’t resist.

MP: Do you remember that Greek statesman who whispered into the ear of his colleague, because the crowd was just cheering what he said: ‘Have I said something foolish?’ When you look at some of the people who are supporting you and some of the sources of your support, do you worry that, as it were, the wrong people are cheering?

NB: Yes, I’m aware that some people whose general views I would not approve of support me. My view is that there’s no stopping that. Also, I’ve armed myself with the response to the first time someone says to me: ‘But how did you dare step on that platform because of so and so’s association with this or whatever.’ My response is, provided you’re not a Nazi or a Stalinist or a mass murderer, I’ll sit and talk to you. I mean, Matthew, I’m talking to you without doing due diligence. I have no idea what crimes you’ve committed, what abuse you’ve committed. I’m here to talk about something we both are interested in. I’m not tainted by association with you, whatever you’ve done. Maybe politically, that’s naive, but there’s nothing I can do about it.

MP: And the whole Brexit thing: your writing has nothing to do with Brexit as far as I can tell. It doesn’t make you a Brexiteer, does it, to believe that there is good in empire?

NB: One big fly in Richard Drayton’s ointment is I voted Remain. I mean, I do have some Brexit sympathies, and I want Brexit to succeed as best it can now we’ve done it. But I’m not a cardboard cutout right-wing little Englander who wants the past to return. And I make quite clear at the end of my book, Britain’s imperial moment has finished, for good and for ill, for ever. It’s just that I want us not to throw the liberal humanitarian baby out of the imperial bath water. There were traditions and commitments there that were admirable, and I want us to continue to pursue those.

*****

MP: There’s one argument I have sometimes found myself using in defence of empire, and that is this: if we British hadn’t occupied these countries and ruled them as colonies, someone else would have and they would probably have been worse than us – the Belgians, for instance, and what they did in the Congo.

NB: I think we can certainly say that whatever we did, it was better than what some people did do. Maybe there was also a power out there that could have done even better than we did. We made mistakes. We committed crimes. But the centre, London, was driven to a significant extent by Christian, liberal humanitarian concerns.

MP: There really is no defence of early 20th- century Australian treatment of the Aboriginal people, is there?

NB: No.

MP: We just have to say that it was appalling.

‘When you look at some of the people who are supporting you, do you worry that the wrong people are cheering?’

NB: Yeah. By the way, one of people’s complaints about me is that I’m not a historian, I’m just a theologian, to which my response is: I’m a moral theologian, I’m an ethicist. I deal in ethics. And my book is an ethical account of empire. And on that, I’m qualified.

MP: I wouldn’t dispute any of what you’ve just said, but it does strike me that I was brought up as a child to feel proud of Britain’s past, proud of empire, proud of many things that people in generations before me had done that had actually nothing to do with me at all. If we are entitled to feel pride about what our forebears have done, would you agree that we are obliged to feel shame also at what our forebears have done?

NB: Absolutely. I mean, I’m a Christian. I’m into sin. I look back at our imperial history and there are moments that fill me with great shame. But in a sense, that’s human life. There’s parts of my own life I feel shameful about. And I think we should feel there are parts we certainly should feel shameful about and disappointed our forebears didn’t do better – and they instruct us to do better in the future. But also there are things about our imperial past: the abolition of the slave trade and slavery. European slavery was absolutely dreadful. But Britain was among the first to abolish it.

MP: I, too, am proud of our record in leading the field in abolishing slavery. But then I think of the way the slave market in Zanzibar carried on to the life of my own grandmother. There was still a slave market in Zanzibar, the accounts of slaves arriving at the port of Zanzibar from the mainland, and because they were ill or sick, being tipped into the sea because there was a head wage payment on all the slaves who came into the market. It fills me with shame.

NB: It fills me with horror. The British Empire was not all-powerful, and in some parts of the world, for some reason, we had to bring our influence to bear. Gradually – we couldn’t simply make it happen. Zanzibar was one of those places.

MP: It’s very nice to meet you, Nigel.

NB: Yes, thanks a lot.

Letters: In defence of Steve Baker (by Steve Baker)

It’s not cynicism

Sir: I was amazed to have suffered the projection of so much cynicism in return for my plea that no one should suffer hate for their identity (‘The cynicism of Steve Baker’, Toby Young, 21 January).

The simple truth is that one of my staff is out as a trans man. Another is a proud gay man with a non-binary partner. I like and admire them, and I have heard what they put up with. I am glad to be their ally. My staff still suffer abuse because of their sexual and gender identities, and I wish for them to live their lives without that abuse. This ought not to be controversial.

My team and I have genuinely been shocked that a benign tweet about supporting the LGBT+ community could spark such an aggressive backlash. Ultimately, my tweet and the reactions to it are about tolerance. As a straight, happily married man, I have never had to wrestle with issues of sexual or gender identity. As far as I know, neither has Toby. But just because we have never shared people’s experiences does not mean that we cannot listen to their concerns. Indeed, the only way that we can avoid the extremes of the social justice movements is to come together as a society and discuss our complicated problems.

Some argue that I did not do so on same-sex marriage, but I would reply that is exactly what I did. I voted against not because I want to force social conservatism on to others, but because my strong view has long been that marriage law needs serious reform. To all those who have accused me of giving up my ideology in pursuit of my own career, please take stock. A desire for minorities to live their lives free from attacks can just be that.

Toby, I know you have a long interest in losing friends and alienating people but it is not too late with me, yet!

Steve Baker MP

High Wycombe, Bucks

Lead role

Sir: Apropos bison, Paul Whitfield, director of the Wildwood Trust, is quoted in The Spectator saying: ‘It’s exactly the same as taking your dog for a walk across a farm. If you’ve got a field full of bullocks and you take a dog off the lead, you’re an idiot’ (‘The beast is back’, 28 January).

No, you are not. If you walk through a field of bullocks with your dog on a lead, neither you nor the dog can get out of the way if the bullocks come too close. Let the dog off the lead when you must (not before) and it will normally outrun the bullocks and allow you to reach safety. The increase in incidents of people trampled by cattle is largely due to this misconception. Dogs are not always best on leads in an emergency.

James Beazley

Newmarket, Suffolk

London’s slump

Sir: I agree with Rory Sutherland’s comments about London (The Wiki Man, 28 January). Living ‘in the north’, I have always been thrilled by the capital. I was however disenchanted after climbing off the peak-time LNER Newark to King’s Cross train last week. We had a dispirited trudge to the Department for Transport through streets piled with rubbish bags, past empty shops and offices. The architecture always inspires, but Rory is correct that things are now better in most northern towns and cities than in London – most certainly the pavements and parks are better maintained.

Roger Hage

Grimsby, Lincolnshire

Wind problem

Sir: ‘When the wind blows’ (Barometer, 28 January) illustrates the wide variation and non-dispatchable nature of wind-generated electricity. The UK’s aspiration to be ‘the Saudi Arabia of wind power’, with a capacity of 50 MW requiring a coverage about four times the area enclosed within the M25 (or 45 times the area of the Isle of Wight), is meaningless during inevitable Dunkelflaute periods when the wind does not blow.

Profs Peter Edwards FRS & Peter Dobson OBE, University of Oxford; Dr Gari Owen, Annwvyn Solutions, Bromley

Mincing words

Sir: The overcomplication in America of the English language and the use of euphemisms was well described by Lionel Shriver in her excellent piece on new jargon (‘You can’t say that!’, 28 January).

My late husband, John Dyson, wrote a concise handbook for teenagers called The Motorcycle Book. It was published in 1977 and there were several European editions, all equally concise. However the US edition, ‘translated’ into American, was nearly twice as long. In the original English edition, John wrote: ‘If you skid under a bus, you are dead.’ Translated into American, this brief sentence read: ‘If you have the misfortune to slide under an oncoming passenger transit vehicle, you are likely to suffer a terminally unpleasant experience.’

Kate Dyson

London SW13

Stamps of beauty

Sir: Joseph Addison’s opinion (‘Notes on … Stamps’, 28 January) that postage stamps have been aesthetically barren for a century cannot go unchallenged.

The Falklands Islands 1933 centenary set is universally acknowledged as a masterpiece of design and one of the most beautiful ever issued. In the following three decades many former Commonwealth countries produced similar long definitive sets, again in the bicoloured recess-printed format which has delighted collectors ever since. In more recent times, Czechoslovakia, France and Sweden have employed internationally famous master engravers to produce miniature masterpieces. While it is true that today too many postal administrations produce a welter of income-generating tastelessly designed stamps which see no postal use, there are still beauties to be found.

David Wright

Whitstable, Kent

Write to us letters@spectator.co.uk

The dangerous myth of degrowth

Britain is beset by low productivity and stagnant growth, and things are not getting better. In the public sector, productivity stands at 7.4 per cent lower than it did before the pandemic. Until we can generate more growth in the economy, we cannot grow richer and real wages cannot grow.

An uncontroversial statement, you might think – even if opinions vary on what to do about it. But no. There are people who genuinely don’t want economic growth, who think it an evil that must be ended. Take a comment piece published late last year in the normally sober pages of the scientific journal Nature. Under the title ‘Degrowth Can Work’, it declared that: ‘Wealthy economies should abandon growth of gross domestic product (GDP) as a goal, scale down destructive and unnecessary forms of production to reduce energy and material use, and focus economic activity around securing human needs and wellbeing.’

The lead author was Jason Hickel, a visiting fellow at the LSE who on Newsnight in 2017 came up with the unusual theory that there are too many jobs in Britain. Humans, he said, are ‘overshooting our planet’s bio-capacity by 60 per cent’, and the only way to save ourselves is by ‘introducing a basic income and a shorter working week which would allow us to get rid of unnecessary jobs and redistribute labour’. Never mind the pain that follows every time GDP growth dips into the red. Never mind the despair created by falling real incomes. If we all worked less we would be far happier. Who gets to decide what is an ‘unnecessary job’, Hickel didn’t say. Many, I suspect, might well choose to nominate the LSE’s visiting professorship in International Inequalities as one of the jobs to go.

Another of the Nature authors is Tim Jackson, who runs a green thinktank called the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. Jackson has written a book called Prosperity Without Growth, and accused Rishi Sunak of pursuing a ‘fetish’ of growth. It is clear, he says, that ‘we’re already living in a post-growth world. And it’s time to take that challenge seriously. To focus on protecting wellbeing. To distribute wealth fairly. To invest in the care economy. To improve education’. That tax revenues from healthy businesses might be useful in improving education and the care system does not appear to enter his thinking.

Then there is Bill McGuire, a volcanologist who’s now emeritus professor of geophysical and climate hazards at UCL. He has called for ‘the contraction of the global economy until it reaches a sustainable steady-state that fits with a level of greenhouse gas emissions compatible with keeping rising temperatures this side of the 1.5 degrees guardrail’. For McGuire, the government’s ambition for ‘green growth’ doesn’t cut it – no, to save the world we have to shrink the economy: less wealth, less stuff. Especially less stuff. In June, McGuire tweeted a photo of a container ship arriving at Felixstowe with what he said was 24,000 containers. His caption read: ‘More than anything, this image encapsulates everything that is wrong with our society.’

People who express disgust with consumerism tend to disapprove of other people’s and overlook their own

But how did he know what was inside all those containers? Was it all frivolous stuff like toys for Christmas crackers or might there have been, say, some PPE bound for NHS hospitals? Unless McGuire wears only locally sourced knitted underwear, my guess would be that something on that ship, or another like it, is found in his home.

It would be easy to dismiss the ramblings of Marxist academics. After all, the idea of ‘degrowth’ has been around since the 1970s without obviously harming anyone. The term, it seems, was coined by the Austrian-French economist André Gorz in 1972, the era of E.F. Schumacher’s book Small Is Beautiful. Hickel has written the similarly themed Less Is More.

Yet the idea that economic growth is an evil seems to have become a lot more mainstream of late – fed, inevitably, by climate hysteria. One of the degrowth movement’s bibles is a bestseller called Doughnut Economics published in 2017 by Kate Raworth and inspired by a diagram she drew when working for Oxfam. It consists of an inner circle where people are impoverished and suffer from poor health, education and so on as a result. Then there is a ring in which everything is just right: the world is consuming just enough to make everyone happy. Beyond that is an ‘ecological ceiling’, outside which lies overconsumption, with attendant disasters such as biodiversity loss, pollution and climate change.

It is a crude and preposterous thesis that doesn’t stand up to examination. There is a weak correlation between wealth, pollution and overconsumption of resources. Some of the most polluting societies in history have been relatively poor, such as the former Soviet Union, which out-belched the world in toxic smoke and effluent but failed to feed its people properly. The English woodlands were mostly stripped in medieval times; in our vastly wealthier country we are replanting them at record pace. The thesis ignores the possibility that technology could ever make things cleaner and consume fewer resources.

Nonetheless, as I say, such attitudes appear to have seeped into the wider population – including among people unlikely to have read Raworth or Hickel’s books. Last month, the National Grid launched a scheme to reward those who used less electricity between the hours of 4.30 and 6 p.m. to try to avert blackouts as an anticyclone becalmed the nation’s wind turbines. It is not surprising, with energy bills so high, that people sought to take advantage of the chance to save £20 (although in practice some complained they were credited only five pence). Yet what was surprising was the zeal with which some reacted. Turning off their domestic appliances became raised to a matter of religious observance. A woman from Inverness told the Guardian how she and her partner brought dinnertime forward to 4.30 and then sat with candles and wood-burning stove. They had even turned off the electric foot-raiser on their sofa. ‘If this can help prevent the National Grid using coal-fired power then we’ll feel like it was really worth it. Part of this for me is learning how to deprive myself of something,’ she said.

There’s the point: it is one thing to advocate the end of economic growth if you have no actual fear of poverty. If you are struggling to keep yourself warm and fed, on the other hand, the idea of self-denial – still less of shrinking the economy – is going to have rather less appeal. Degrowth is a middle–class luxury, an indulgence to be conducted from the comfort of your sofa with its electronic foot-raiser. It revolves around matters of taste as much as the environment. People who express disgust with consumerism have a tendency to disapprove of other people’s while overlooking their own. Those who boast of buying less stuff are often not averse to the odd skiing holiday – as the holiday snaps of Extinction Rebellion activists have attested.

Bizarrely, the idea of degrowth trips off the tongue of some of the very same people who on another day will complain the loudest when incomes fall. Former Green party leader Caroline Lucas denounced Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement as ‘ideologically driven Tory austerity’. The problem, evidently, is Tory austerity rather than the much better-flavoured Green party austerity, because Lucas doesn’t seem to be a great believer in people becoming better off. In 2021 she complained that ‘The endless pursuit of economic growth, as the lodestar of government policy, is what is driving the climate crisis’. If a shrinking economy does not amount to austerity, I don’t know what does.

If you are a nurse, ambulance driver, driving examiner or a member of the many other groups who have been striking about the failure of your wages to keep pace with inflation, your enemy is not Hunt; it is the degrowthers. It is they who want to reduce the buying power of your wages year on year. If a Conservative minister were to say ‘Nurses, why don’t you forget your pay claim and learn to live life with less, to concentrate on mental wellbeing rather than material goods?’ the sky would fall in. Yet the traditional left, which seeks a fairer slice of the national cake for working people, has yet to collide head-on with those who want to reduce the size of the cake altogether. These ideologically opposite positions cannot evade each other for ever. Sooner or later the likes of Jason Hickel will find themselves in the same room as Mick Lynch and will have to argue it out.

Liz Truss was ridiculed for talking about the ‘anti-growth coalition’. She certainly went over the top, making it out to include people who do favour economic growth, such as some of her former cabinet colleagues. Yet there really is an anti-growth tendency, whose ideas are filtering down into terribly well-meaning middle-class people. Anyone who thinks the Tories have been inflicting ‘austerity’ on the country for the past 13 years should be looking over their shoulder for the people who genuinely want to shrink the economy.

Is corporate ‘purpose’ falling out of fashion?

Does a change of chief executive at Unilever, the British-based shampoo-to-Marmite multinational, signal the demise of the fashion for corporate ‘purpose’? Alan Jope, who steps down in July, drew scorn when he declared that every brand in his portfolio should ‘stand for something more important than just making your hair shiny… or your food tastier’. His reputation was also dented by the failure of a £50 billion bid for the consumer arm of the pharma giant GSK – but it was his preaching about sustainability and purpose while Unilever’s performance continued to flag that ultimately cheesed off his shareholders.