-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Why Democrats shouldn’t celebrate the charges against Donald Trump

The indictment of former president Donald Trump as part of an investigation into hush money paid in 2016 to an ex porn star is striking for a number of reasons. There is its historic nature, unprecedented and indicative of the weaponisation of government entities by partisans who head them. Trump is accused of having an affair with Stormy Daniels and paying her to keep quiet. The allegations – which Trump has denied and says amount to a ‘political persecution’ – are questionable. No serious legal scholar believes they could pass muster. And then there is the total bifurcation of reaction: for Democrats, they are approaching this conclusion with less joy than solemnity, a gritted teeth approach to revelations that might once have had them dancing in the streets. For Republicans, they seem far less concerned: they think it will even help Trump, and certainly not hurt him, with the American electorate.

It’s possible that everyone is wrong about this. The GOP primary voter may certainly run to back Trump in the face of this attack, but after Russiagate, two impeachments, and the Mar-a-Lago raid, how much more can be done to solidify his support?

For Democrats, it’s difficult to weaponise this case

As for independent voters, it’s certainly possible the cloud of indictment could turn some of them off — but they were also people who forgave Trump, infamously and surprisingly, for the NBC News ‘grab em’ tape.

And for Democrats, it’s difficult to weaponise this case – which is led by Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg – because of how abnormal and baseless it seems. It is hardly conducive to their more powerful message of election denialism. In the post-Bill Clinton era, are hush money payments even a crime?

The fact that this seems like a partisan case based on a technicality, and a stretch of one at that, is likely to drive the narrative — one reason why Henry Olsen writes in the Washington Post that Bragg was wrong to pursue this case given the precedent it sets for conservative prosecutors in red state venues:

‘Regardless of what people think about Trump or the facts of the case, it’s not hard to see the problem. New York state’s entire judicial process is controlled by Democrats who could lose their positions in party primaries. Alvin Bragg, the district attorney overseeing the case, boasted during his campaign that he had sued Trump or his administration more than 100 times during his tenure in the state attorney general’s office, something he probably did to curry favour with primary voters who loathe Trump. Every New York state judge who would either try the case or hear an appeal is elected on a partisan basis, too. It would take a lot of courage for a judge to apply the law fairly and potentially ignore their voters’ desire for vengeance. Imagine if Joe Biden were prosecuted after his presidency in an overwhelmingly Republican jurisdiction. Democrats would rightly howl if an ambitious GOP district attorney did to Biden what Bragg is doing to Trump.‘

The John Edwards case, the multiple Clinton cases and numerous other political designs for nondisclosure and hush money payments have been around for a long time in American politics.

In 1920, after Warren Harding gained the GOP nomination for the presidency, the Republican Party decided that rather than risk the discovery of a series of hundreds of love letters he had written to his neighbour and mistress Carrie Fulton Phillips, they sent her and her husband on an all-expenses paid vacation to Asia — along with a lifetime stipend.

The point is that as unseemly as these things are, they are not new — and Americans, with rare puritanical exceptions, are not interested in them. To engage in such historically unprecedented legal assault on a former president sets a new standard for how far lawfare partisans are willing to go — and it will only further, in the short term at least, the levels of distrust among voters for all the systems we are supposed to have faith in as citizens of this country.

A version of this article appeared originally on Spectator World

Why did Guy Pearce apologise for this trans tweet?

Hollywood actor Guy Pearce has apologised for posting a pro-trans tweet. That’s where we’re at now with the culture war. The Twitterstorms don’t even need to make sense anymore, as the bizarre case of the LA Confidential star’s recent comments about trans actors has made abundantly clear.

Pearce took to Twitter earlier this week and posed a string of very good questions. ‘If the only people allowed to play trans characters are trans folk, then are we also suggesting the only people trans folk can play are trans characters?’, he asked. ‘Surely that will limit your career as an actor? Isn’t the point of an actor to be able to play anyone outside your own world?’

Pearce was responding to the ongoing debate about identity-specific casting, and the backlash to so-called cis (a person whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth) actors being cast in transgender roles. In 2018, Scarlett Johansson stepped back from drama flick Rub and Tug, after her casting in the role of a trans mobster sparked an almighty online backlash. Similarly, Eddie Redmayne has been hauled over the coals for his starring role in The Danish Girl, a biopic of Lili Elbe, one of the first recipients of ‘sex-change’ surgery.

What Guy Pearce said was absolutely correct

Pearce was making a point that almost everyone, deep down, agrees with. Namely, that it is ridiculous, not to mention impractical, to expect actors only ever to portray people who reflect their own life story. What’s more, he was clearly expressing particular concern for the effect that this identitarian casting has on trans actors, who he thinks will be consigned to a kind of casting ghetto where they can only play trans roles.

Nevertheless, the tweet reportedly sparked a ‘firestorm’ among some of his followers. Pearce has now deleted the message and issued a statement, as if he’d been accused of a crime. In it, he apologises for being ‘insensitive’, cravenly acknowledging the ‘Full House’ of privilege he enjoys as a straight, white bloke. He says he still stands by his comments about casting, but that he didn’t want to ‘throw the subject on to one minority group’.

All of which begs the question: why apologise, then? But I suppose it says something about the gender wars, celebrities’ terror of being seen to be on the wrong side of it even briefly, and the fury that can meet the most miniscule transgression, that Pearce felt he had to cave in to his critics anyway.

It’s all so pathetic. Not least because what Pearce said was absolutely correct. The rise of identity casting has upended the craft of acting as it was previously understood. After all, actors have always been expected to step outside themselves and embody someone totally different. But about five minutes ago the industry suddenly decided that minorities simply must play minorities, even if someone not of that group could, with a good performance, portray a trans or gay person convincingly.

This is often called for in the name of giving more opportunities to minority actors. Meanwhile, white, straight Hollywood stars are told to stop sobbing and make way. But aside from corroding what performance is supposed to be about, this new approach also risks limiting the very minority actors it is supposed to liberate, ushering in a whole new era of typecasting. This is precisely what poor old Guy was getting at.

Actor Chris New – star of acclaimed 2011 indie film Weekend, and himself an out gay man – spoke powerfully about the constraints of identity casting in an interview with the Guardian in 2019.

‘Being out has done nothing but restrict my career. In the current cultural climate I am invited to participate only on the basis of my supposed oppression’, he said. ‘Any role where the character’s sexuality is their defining characteristic I turn down. Which means I don’t work very much.’

The impossible expectation that actors should embody their characters’ ‘lived experience’ to a T has also led to some pretty nasty social-media skirmishes. In 2018, Aussie actress Ruby Rose was announced as the next Batwoman. The female caped crusader is gay in her modern incarnation. But even though Rose herself is a lesbian, critics were incensed because she isn’t ‘gay enough’ – on account of her being ‘genderfluid’. (If I could explain the logic here I would.) Rose left Twitter and closed down comments on her Instagram as a result.

What we see here once again is the regressiveness of identity politics. Rather than liberating minority actors, identitarian casting is constraining them and calling it progress. The new woke typecasting is hardly any better than the old. And Guy Pearce shouldn’t have apologised simply for calling it out.

What Prince Harry gets wrong about therapy

Prince Harry’s endorsement of therapy will likely turn some of us off ever seeking it out. Insisting that therapy has changed him for the better, he is urging his family to partake so that they too can ‘speak his language’ of simultaneously loaded and empty terms – such as ‘authenticity’. ‘If I didn’t know myself, how could members of my family know the real me?’ he said. This non-sequitur subverts the conventional wisdom that sometimes others can know you better than you know yourself.

Yet tiring as all the Prince’s interventions are, a peremptory dismissal of psychoanalytic practice would be a mistake. In fact, psychoanalysts would probably refuse to accept the Prince is speaking their language anyway. Psychiatrist Dr Max Pemberton said that Harry is ‘promoting yet another quack therapy’ and has ‘forfeited any right he might have had to be seen as a credible representative for mental health charities’. Fortunately for those in need of professional help, Harry has profoundly misunderstood the very thing he endorses. It’s not just about you. It’s about our shared society.

Prince Harry is not alone. Many more have misunderstood Sigmund Freud’s famous and strangely plausible (especially for women) thesis that boys have an unconscious sexual infatuation with their mothers. While it titillates every bored psychology student, the serious lesson of Freud has been lost through the ages – no thanks to his successors.

Thinkers who followed in his wake tended to interpret repression as something to mitigate against, condemning structures that might perpetuate some form of self-restraint. Freud was particularly displeased with Wilhelm Reich. Once a protege of Freud’s, Reich began to develop and test ever more radical, dangerous and perverted treatments. Paired with his sexualpolitik, it suffices to say his career, and life, did not end well (in jail, actually).

Philip Rieff predicted the rise of the ‘therapeutic man’ who is ‘born to be pleased’ with ‘nothing at stake beyond a manipulatable sense of wellbeing’. Sound familiar?

Freud described Reich as ‘passionately devoted to his hobby-horse, who now salutes in the genital orgasm the antidote to every neurosis’. While, as Adam Phillips points out in an excellent essay, Reich thought that society was only as good as the involuntary orgasms of individual members, Freud was interested in the more complex task of stabilising society by training individuals to voluntarily practice ‘renunciations of instincts’.

Another fraudulent Freudian who eschews inhibition for the sake of unbound desire is Simone de Beauvoir. Here’s is her take on marriage: ‘I think it’s a very dangerous institution – dangerous for men, who find themselves trapped, saddled with a wife and children to support; dangerous for women, who aren’t financially independent…’

De Beauvoir’s dim view of marriage stems from her withering appraisal of dependency altogether. For her, dependency is an undignified status that detracts from the most important feature of human life – individual autonomy. But are two mutually dependent people such a problem for freedom? What if we saw the discipline required to be a faithful spouse as upholding the determination of both individuals to achieve security and stability? More broadly, what if we associated self-restraint less with prudishness and censorship, and more with responsibility, or even civility?

It is here that Reich and de Beauvoir part ways with Freud. The social liberalism that stemmed from the 1950s and is morphing into an indignant therapeutic defence of feeling free does not have its roots in Freud. Despite its allure, Freud did not consider ‘unbridled gratification’ a sustainable way to live, warning that it ‘something penalises itself after short indulgence’.

Freud did in fact influence one thinker in the opposite direction to Reich and de Beauvoir: Philip Rieff. Once married to Susan Sontag, Rieff lived a comparably sedate life, teaching sociology at the University of Pennsylvania for more than 30 years. An understudied and largely forgotten thinker, he predicted the rise of the ‘therapeutic man’ who is ‘born to be pleased’ with ‘nothing at stake beyond a manipulatable sense of wellbeing’. Sound familiar?

Prince Harry is Rieff’s ‘therapeutic man’ par excellence. In Spare, Prince Harry gifts anyone looking to test his shallow therapeutic outlook with the following passage:

We are primarily one thing, and then we’re primarily another, and then another, and so on, until death – in succession. Each new identity assumes the throne of Self, but takes us further from our original self, perhaps our core self – the child… there’s a purity to childhood, which is diluted with each iteration.

This nostalgic call to return to some original self, an undiluted prototype from Eden, is pickled in therapeutic brine. It is sealed off from any summons of loyalty, obligation or discipline – those higher things that challenge our instinct to live according to every carnal twitch.

Rieff sought to recover respect for behaviours such as reticence, secrecy and concealment of self. He observed that these were once aspects befitting of a virtuous man – but now they have come to be seen as pernicious pathologies. While Rieff’s therapeutic man is beholden to indulge each and every individual desire in the name of authenticity, the virtuous man freely chooses self-restraint. He inhabits roles and makes himself seen. He answers summons and happily conforms to the right cultural norms and social expectations. The roles we all play in our families, communities and national life are not – as Prince Harry might suggest – counterfeit or diluted selves, but the only way to live happily. Ironically, this is also the ultimate goal of therapeutic man.

The therapeutics would have you believe that resisting the summons of duty is a minor offence; a simple expression of a personal preference to live autonomously (read, isolated) and authentically (read, indulged). But actually, resisting the summons of duty is a violation of cosmic proportions, and self-destructive too.

Rieff – and Freud – knew this; that living isolated, indulged and evading duty would not only depress the individual but destabilise wider society too. We can see this with a quick glance at our own social order. The whims of the therapeutics are well served by current trends that seek to destroy bonds of trust between families and communities, inherited from history, that sustain our common life now and for future generations.We erase history that doesn’t fit our fantasy; slough off the domestic care of children and older people; eliminate biological differences between the sexes; and expunge national borders.

It’s time to take Rieff’s tonic. Inspired by a conservative reading of Freud, we must respond to the restraining forces that emerge from our associational life with others and deter us from toppling statues or leaving our spouses. This is not inhibition; this is order. We must face our fear of responsibility if we want to live genuinely free from the unceasing demands of our own desire.

Of course, this poses a political challenge. How can the state shape a social order that facilitates – rather than undermines – self-restraint? Marriage, for instance, is not the dangerous institution de Beauvoir bewailed, but one that orientates both parties away from themselves and towards some common good – not only between themselves but society as a whole, especially if you do your bit to save us from demographic collapse.

Other structures can bestow similar advantages. The associational life maintained by places such as youth clubs, playing fields and village halls build reciprocity, trust and a well of social support. And the same goes for the patriotic bind that comes with national identity and national security.

The state should be in the business of creating opportunities for people to answer the summons of civilisation and participate in associations beyond themselves in the family, community and the nation. A system of taxation that supports the care economy in every household; economic planning that protects local industry and pride of place; a ban on pornography.

If you baulk at the thought of the state taking an interest in such affairs, then you have an over-realised liberal view of the state, and its proper role to pursue a substantive vision of the good life. If market forces and state services were made to strengthen mediatory institutions in civil society, then a whole new political regime would unfold. Some call it post-liberal. I call it plain conservatism. It could happen. It’s what Freud would have wanted.

A beautiful monster: the Aston Martin Vantage reviewed

The new Aston Martin Vantage is shorter and hotter than the DB11: a smaller, truer sportscar, though slightly less elegant. ‘Gentlemanly’ is what the copywriter calls the DB11, but this is a ‘hunter’ and ‘predatory’. Ferraris, meanwhile, are a little too hot for me – though I accept that they are sublime, if Ferraris are your thing – and the Toyota Supra, which I love – even shorter, even hotter, much cheaper – doesn’t make quite the same impression on the A30. People (I mean men over 40) love Aston Martins. They view them as an expression of British pride, and coo over them like babies, by roaring past, overtaking, and slowing down, and then insisting you overtake them in turn. The whole encounter is managed by hand signals and engine snorts, and it is delightful.

This is the first new Aston Martin sportscar since the Vantage appeared in 2005 – the DB11 and the DBS Superleggera are grand tourers, and the Valhalla and the Valkyrie are eerie beasts, supercars not for the likes of us – which is big news for this column, even if James Bond, who peels mangoes for infants now, acts like a man longing for a Volvo and its peerless safety record. Nothing lasts forever. Still, there’s me.

This is the ‘baby’ – or the entry-level – Aston Martin (everything is relative). I have the coupe, and it is a beautiful monster. It is exquisite in looks, of course: but then I’ve never seen an Aston Martin that isn’t beautiful. (People who say the British are bad at decorative arts don’t notice our cars.) That’s why the King, who is all aesthetics – I have seen his gazebo – loves them. It’s all insinuating curves, like a cello, just made of bonded aluminium. The invocation of a woman’s body isn’t subtle, and it isn’t meant to be. This is a car for lying on, in and under: of course, James Bond met it in violence and lust before he got boring. (Cars have a fantastical ability to mirror.) The grille is expansive: the headlights are slender, and lovely; the interior is a room of your own with warmth and music, or not. It smells of – well, money. Just money.

It’s all insinuating curves, like a cello, just made of bonded aluminium. The invocation of a woman’s body isn’t subtle, and it isn’t meant to be

That’s the beauty: now for the monster. It’s inevitable – ironic, faintly heartbreaking – that, as we reach the end of petrol cars, they are closer than ever to perfection. If cars are art for men who don’t know they love art, now they are cursed by the certainty of losing it. Aston Martin has a deal with Mercedes – its ownership history is confounding, and this suits the fragility and poetry of the products, though I suspect accountants don’t get out of bed for metaphor alone – and this has produced a 4.0-litre twin turbo V8 engine, which will shoot from 0-60mph in 3.6 seconds, with a top speed of 195mph: a mad thing to squeeze into a two-door car.

Those are just numbers, of course, keystrokes, which give you nothing of the sensation of driving it. It’s childlike, I suppose, at least partially, and the rest I am afraid of: picked up and hurled dreamward, it is part lover, part parent, part friend. I always feel renewed in an Aston Martin, which, when asked, does as fair an impersonation of Verdi’s ‘Dies Irae’ as a car can manage. I cannot know if this sensation continues, as I have never owned one.

A glorious car then. It has other permutations – the F1 edition (sold out, they only made 333 of them) has a spoiler (a wing) on the back, which is for Kenickie Murdoch from Grease, not me, and you can have a V12 if you want to take off, but I don’t drive fast enough for it. But I can’t think of much, legal or not, I wouldn’t do for the V8 Roadster. I just configured one on the website – black like my soul, and Adrian Mole’s bedroom, there was no baby pink option – and though I was able to post my configuration on Facebook, they won’t tell me how much it costs unless I email them, at which point I will have to confess I am a fantasist.

Petrol cars are ebbing, as I said: you won’t be able to buy a new one after 2030, by which time I hope the experience of charging an electric car isn’t the same as the one I had at Land’s End yesterday, which was pre-fisticuffs near a Vauxhall Corsa in the rain. If you can afford an Aston Martin Vantage – it’s £130,000 and rising – buy one now, before they roar into history. Buy this one. Nothing lasts forever. Nothing should.

The dark side of Ted Lasso

You’ll know where you are with Ted Lasso – the third season of which has just started on Apple TV – as soon as you hear the Marcus Mumford co-written theme song. It peddles a sort of sub-Coldplay uplift, with a lot of big, meaningless anthemic ‘yeah’s in the chorus. Bright, accessible, catchy and instantly forgettable, you still enjoy hearing it every time you watch a new episode.

And that’s the show in microcosm: cheery, amusing and utterly inconsequential. Yet somehow the Jason Sudeikis vehicle has become not only Apple TV’s biggest hit to date, but the most Emmy-nominated comedy in recent years. It has won for everyone from Sudeikis (who has two Emmys and two Golden Globes for his work on the show) to Brett Goldstein and Hannah Waddingham, who play, respectively, the surly veteran footballer Roy Kent and Rebecca, the owner of AFC Richmond, the football club that Lasso is hired to coach with hilarious consequences.

At a time when most situation comedy is either insipid or unfunny, there’s something heartening about the way that Ted Lasso takes its potentially clichéd situation (‘fish out of water American ends up charming all those stiff-assed Brits’) and manages to make it fresh and amusing. In addition to the lead actors, there’s a fine selection of British comic thespians on hand, from the ever-unctuous Anthony Head as Waddingham’s suave but appalling ex-husband and business rival, to Downton Abbey’s Jeremy Swift as Higgins, AFC’s bumbling director of football operations. It’s also impossible not to enjoy James Lance as the journalist-turned-author Trent Crimm, always ready with an awkward question for the ever-cheery Ted.

It’s frustrating that Ted Lasso constantly flirts with the idea of darker and more interesting territory, only to return to a comfort zone of hugs and one-liners

Such is the show’s popularity that the cast (including, naturally, Crimm) headed to the White House last week to discuss the issue of mental health. This is something touched on throughout Ted Lasso: the apparently ever-cheery Ted underwent a breakdown of sorts in the first season after being unable to cope with the pressure of separating from his wife and no longer seeing his son regularly. At the White House, the ever-cheery Sudeikis said: ‘No matter who you are, no matter where you live, no matter who you voted for, we all – probably, I assume – know someone who has – or have been that someone ourselves, actually – that’s struggled, that’s felt isolated, that felt anxious, that felt alone.’

Warming to his theme, Sudeikis declared: ‘And it’s actually one of the many things that, believe it or not, we all have in common as human beings, right? And so that means it’s something that we can all, you know, and should talk about with one another when you’re feeling that way, when we recognise that someone is feeling that way.’ He concluded: ‘We encourage everyone – and it’s a big theme of the show – to check in with your neighbour, your co-worker, friends, family, and ask how they’re doing and listen sincerely.’

All most decent and commendable, and a soft plug for the show in which he stars, to boot. Yet for all the talk of mental health issues, it’s frustrating that Ted Lasso constantly flirts with the idea of darker and more interesting territory – hence its protagonist’s breakdown – only to return to a comfort zone of hugs and one-liners. For a remarkably profanity-heavy series, there’s something oddly safe and tame about its frictionless universe. Even as Nick Mohammed’s treacherous kit man-turned-assistant coach-turned-rival coach, ‘Nate the Great’, has perhaps the show’s most interesting arc, one can already see the soapy redemption being teed up for his character. No doubt there will be hugs.

For my money, the most interesting episode of Ted Lasso by a country mile, ‘Beard After Hours’, was also its most divisive. In the second season, Ted’s taciturn right-hand man, Coach Beard, heads off into the London night, and strange things happen. The title nods to Martin Scorsese’s classic After Hours, and there are also nods to James Joyce’s Ulysses, particularly the ‘Circe’ section of the book. For an hour or so, it entirely abandons the cutesy ‘Aw shucks’ uplift that it has hitherto majored in, in favour of something much weirder and darker.

It’s fascinatingly strange and proof that, if the writers put their minds to it, Ted Lasso could yet be something unique rather than merely pleasant. But back to those ‘yeah’s, eh?

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s World edition.

Are MPs doing the ‘chicken run?’

It’s a sign of the tensions within the parliamentary Conservative party that talk of colleagues swapping constituencies is currently a major talking point in the Commons tea rooms. This week two more members of the 2019 Tory intake announced that they would not be seeking re-election in their constituencies. Both Nicola Richards and Stuart Anderson released lengthy statements explaining their decision – but neither MP explicitly ruled out standing again in another seat. Keiran Mullan has meanwhile declined to comment on claims that he will switch from Crewe and Nantwich to the new Chester South and Eddisbury seat.

Some Tories disparagingly refer to the ‘chicken run’ – the term coined to describe the trend of Conservative MPs fighting to secure safer seats ahead of New Labour’s landslide. David Amess, Nicholas Soames, Brian Mawhinney and George Young were among those who fought for new, safer seats in 1997, earning the label of ‘chicken’, fairly or not. But the key difference between then and now are the extent of the sweeping new boundary changes, which have abolished old seats and created new ones; unsettling numerous incumbents and forcing colleagues to go head-to-head in seats like Penrith and Solway. An especially complicated three-way contest in Hampshire – dubbed the ‘Battle of Waterlooville’ – is due to take place next month between incumbent Suella Braverman, Paul Holmes and Flick Drummond.

Conservative Campaign Headquarters has now established a ‘displacement committee’ to adjudicate on cases involving those MPs who wish to fight a different seat. Colleagues can argue their case for ‘displacement rules’; those unsuccessful can go on the wider candidates’ list. Those given such dispensation by the panel are either placed automatically in the final three candidates of another seat in their region of the country. Alternatively, they are granted an interview with the executive of an association in a different region.

Those involved in this process stress the efforts undertaken to try to ensure every elected member gets a fair shot; they cannot just switch constituencies on a whim and could end up without a seat to stand in. But there are signs that such arguments have not been well received by all MPs. ‘There is real and growing anger in the parliamentary party about all of this’ says one. ‘The optics are that we’re giving up on marginal seats and makes it incredibly difficult for whoever is the new local candidate.’

As well as the scepticism of their colleagues, MPs trying to find new seats in different parts of the country must contend with the modern trend for ‘local’ candidates. There is significant grassroots discontent over the recent membership fee hike, the high turnover in branch chairmen and the circumstances of the last two leadership contests. Activists might therefore be less inclined to aid the search for safe berths for incumbents. In 2019, only one MP – Mims Davies – was able to pull off the feat of successfully switching seats from Eastleigh to Mid Sussex, and that was due in part to the exceptional circumstances of the snap election.

Given the scale of the challenge facing Rishi Sunak, it is highly likely that we will see similar attempts by multiple incumbent MPs ahead of the 2024 election. The question is: will any of them actually succeed?

Humza Yousaf’s debut FMQs descends into chaos

Humza Yousaf’s debut at First Minister’s Questions was never going to be straightforward. The First Minister’s questionable track record in government offered, to use his own words, an ‘open goal’ to his opposition. Scottish Labour’s Anas Sarwar was quick to point to Yousaf’s ‘incompetence’, while Scottish Conservative’s Douglas Ross belittled the new cabinet. But what made Yousaf’s FMQs debut even more chaotic were seven serial interruptions by climate activists.

When the protests eventually stopped – after the public gallery was, in an unprecedented move, cleared bar two groups of schoolchildren – the attacks against Yousaf continued while today’s guest, the ambassador to Iceland, looked on. Riding the wave of SNP division, Ross used Yousaf’s own words against him. Quoting former business minister Ivan McKee, who, like Kate Forbes recently resigned from government, and former MSP Alex Neil, one of Forbes’s backers, Ross criticised the lack of business acumen in Yousaf’s new cabinet, before slamming his ‘divisive’ opponent.

Yousaf appeared to grow more irritable, dismissing Conservative MSP Jeremy Balfour’s question as crying ‘crocodile tears’

‘If Humza Yousaf can’t even unite his own party, how can he unite the country?’ Ross jeered. Yousaf made a jibe at Liz Truss’s tax cuts but seemed to get confused on his plans for the economy. ‘I am building upon our legacy where we have higher unemployment, lower unemployment,’ he said. It was, albeit, a relatively minor gaffe in the scheme of Yousaf’s history.

Sarwar also chose to focus on the First Minister’s track record. During Yousaf’s time as health secretary, over 11,000 children were left waiting longer than the 18-week standard for treatment. Describing the story of one child – who had been waiting longer than the entire time Yousaf had been health secretary to receive treatment – the Scottish Labour leader asked if the First Minister would ‘take this opportunity to offer an apology to the children and families he let down as health secretary’.

Yousaf did apologise, and made the announcement that the Scottish government would be investing £19 billion in the health service in the 2023/24 period. The SNP, Yousaf insisted, would also make sure that ‘our NHS staff are the best paid per year than anywhere else in the UK’, and he pointed out that ‘we have never lost a single day this winter to strike action’. What Yousaf failed to mention is that junior doctors in Scotland are being balloted for strike action. He has already said during his campaign that he will not give medics the pay rise they want. Given 98 per cent of all doctors who voted in England’s ballot were in favour of industrial action, Yousaf’s statement on striking workers looks unlikely to hold much longer.

There was a lot of deflection from the First Minister in today’s FMQs. Yousaf repeatedly blamed Scotland’s lack of independence for the problems facing the government, and the Covid pandemic also provided a handy excuse for the First Minister when forced to defend his record in health.

As the session went on, Yousaf appeared to grow more irritable. He dismissed Conservative MSP Jeremy Balfour’s question about how many of his constituents have not yet received the Scottish Child Payment as crying ‘crocodile tears’. He looked rattled as Labour’s Pam Duncan-Glancy pressed him on why he had no cabinet secretary for social security, nodding to the absence of Ben MacPherson from government. ‘Social security is being led by the cabinet secretary – she’s sitting right there, she’s waving right at you!’ he cried back, gesturing towards his social justice secretary, Shirley-Anne Somerville.

In general, though, the First Minister’s responses felt rather flat. As one hack remarked under his breath, in reference to Nicola Sturgeon: ‘How stale it sounds when it’s someone else saying it…’ For all that Yousaf likes to perform, and can be camera-friendly when he wants, his answers today fell short. His go-to response of blaming the Westminster government for just about everything became repetitive, and yet there were strikingly few solutions to Scotland’s problems. As his opponents highlighted, it will be hard for the Scottish people to trust Yousaf given his own chequered time in government, particularly on health – regardless of this £19 billion investment. Not to mention the First Minister still needs to weather the storm that Forbes’s resignation will inevitably bring. Interestingly, neither Forbes nor his fellow leadership rival Ash Regan were present today.

The protesters weren’t welcomed by anyone, and the fact that one of those thrown out today, retired army officer Mike Roswell, was removed from the Chamber only three weeks ago raises serious questions about how the parliament gets to grips with disruptive activists. But they did make an otherwise dry First Minister’s Questions a little more entertaining.

Is this the reason Harry and Meghan stepped down as working Royals?

Stepping down as working royals would ‘provide our family with the space to focus on the next chapter, including the launch of our new charitable entity,’ Meghan and Harry wrote in their infamous bombshell statement of January 2020.

Just one month before, the Sussexes had launched their Archewell website, with childhood photos of themselves with their mothers, Doria Ragland and the late Princess Diana.

‘I am my mother’s son, and I am our son’s mother,’ the official letter read. ‘Together we bring you Archewell. We believe in the best of humanity. Because we have seen the best of humanity… from our mothers and strangers alike.’

Anybody who has been keeping an eye on Archewell is perplexed

Arche is Greek for ‘source of action.’ According to Archewell’s website, their action would include ‘uplifting and uniting communities – local and global, online and offline – one act of compassion at a time to fuel systemic cultural change.’ Gotcha.

Archewell’s mission statement is all woke buzzwords thrown together meant to mean nothing. Or maybe you have to find the meaning. Maybe that’s the point. Human nature loves a vacuum.

In the first 611 days of Archewell Audio’s multi-million pound agreement with Spotify – the Sussexes branched out from charity to the entertainment business pretty quickly – Meghan and Harry had only managed to produce one 33-minute ‘holiday special.’

Since then, we’ve had about twelve more hours of content from Megs. Her podcast, Archetypes, was all about words that offended her. She signed off the series saying that she will be back for a second season as thanks to this outlet she finally ‘feels seen.’ Who knows if she’ll have anything left to say after the Meghan & Harry Netflix series, her possible memoir and the relaunch of her personal blog, The Tig, or Git backwards.

But now Archewell have released tax filings for 2021 and they show what we all knew to be true the whole time. Meghan and Harry have spent the last three years doing very little at all. The documents show that the couple worked a grand total of one hour each a week at the foundation, racking up a time sheet of 52 hours in a year. Those chickens aren’t going to look after themselves.

Anybody who has been keeping an eye on Archewell is perplexed. In 2021, the charity gave out $3 million (£2.4 million) in grants to refugee resettlement charities and funding for Covid 19 vaccines. It raised $13 million (£10.5 million) from benefactors. The pair also raised just $4,500 (£3,600) in public donations. $10 million (£8 million) came from a single donor, which has since led to speculation that it was handed to the pair by Oprah Winfrey, in return for the interview the Duke and Duchess of Sussex gave in March 2021.

For a company that’s gone through staff like disposable forks, Archewell doesn’t seem like a bad place to work. While Harry and Meghan don’t take a salary for their hard work, CEO James Holt works one hour a week and receives a $59,846 (£48,000) salary and $3,832 (£3,000) in other benefits. This equates to earning $1,224 (£980) an hour.

Finally, after three years of speculating, the truth may be appearing as to why Meghan and Harry stepped down as working royals. While they may claim it was down to institutional racism, tabloids, privacy, or big bad men in grey suits, the real answer may be more prosaic: the life of a working royal means work and that’s something they aren’t willing to do.

Evan Gershkovich and Russia’s descent into thugocracy

It’s a crude but inescapable fact of history that many states had their origins in better-organised bandit gangs. It’s a depressing feature of the present that some states seem determined to slide back into bandit status. While Putin’s Russia retains the institutions of modern statehood, he and his clique of cronies and yes-men have no problem adopting the tactics of the thug – including kidnapping. The arrest of American journalist Evan Gershkovich on espionage charges appears to be the most recent example.

The Kremlin is tiptoeing closer to a kind of ‘North Koreanisation’

Gershkovich, part of the Wall Street Journal’s Moscow bureau, was on assignment in Ekaterinburg when he was detained by the Federal Security Service (FSB). This is the first time an American journalist has been arrested on spying accusations since the end of the Cold War – or perhaps it is better to say his is the first such arrest of the new Cold War.

The FSB claims that he was allegedly trying to obtain classified information, although in the current draconian Russian environment that could have been almost anything. According to an Al Jazeera journalist, Gershkovich was working on a story about how people felt about locals working for the Wagner mercenary group, which the Kremlin would likely have found embarrassing, but which would fall within what we would consider the purview of legitimate journalism. Nonetheless, the FSB is claiming that he was ‘acting on US orders to collect information about the activities of one of the enterprises of the Russian military industrial complex that constitutes a state secret.’

There is a complex relationship between the worlds of espionage and journalism. In fairness, sometimes the two do overlap, although these days it is much more likely that it will be freelancers within the media who have any spook links. So far, at least, there is no evidence that these claims against Gershkovich, a well-regarded member of the understandably dwindling western press corps in Russia, have any weight.

Instead, the inevitably suspicion is that this is linked to the recent arrest of two Russian spies in Slovenia and the conviction of another, Sergey Cherkasov, who had been trying to infiltrate the International Criminal Court.

When Moscow was eager to get former military intelligence officer and arms dealer Viktor Bout sprung from an American prison, it pounced on the discovery of cannabis oil vape cartridges in the baggage of basketball star Brittney Griner and imposed a well-over-the-odds nine year prison sentence on her. Unsurprisingly enough, before the end of the year, Bout and Griner were both free.

Griner had, at least, broken Russian law. So far we have not seen evidence that Gershkovich was doing anything more than journalism – which he was accredited to do by the Russian government. Yet already Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov is rushing to affirm that while it is too early to discuss a possible prisoner swap involving him, such exchanges had taken place in the past and it is necessary to wait and see how the situation develops. That’s as explicit an invitation to a deal as one could expect at this stage.

I’ve never been happy with the clumsy and often misleading tag of ‘Mafia State’ for Russia, and whatever the horrors taking place in Ukraine and elsewhere, ‘terrorist state’ also seems a little too simplistic. Nonetheless, the degree to which the Kremlin seems so willing both to engage criminals as its agents (such as the contract killer whose criminal record was erased in return for his assassination of Chechen rebel agitator Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin) and criminal tactics as foreign policy make it depressingly clear just how far it is devolving into thugocracy.

With this willingness to embrace pariah status, and an almost wilful desire to sever links with the outside world (one wonders how many westerners will continue to be happy travelling to Russia now that kidnap and ransom have become policy) then the Kremlin is tiptoeing closer to a kind of ‘North Koreanisation.’ This is hardly the kind of country most Russians want for themselves, but the more Putinism becomes Juche-with-Russian-characteristics, to invoke North Korea’s ideology of isolation and self-reliance, the wider the gap may grow between Putin and his people, who will be able to do less and less about it.

Gershkovich is the current and most flagrant example, but arguably many or most of Russia’s 140 million people are also Putin’s hostages. Gershkovich, one hopes and presumes, will make it out, though.

How trans ideology took over our schools

Concern with what schools are teaching about sex, gender and relationships has been growing. Parents worry their children are being exposed to inappropriate sexualised content and that they are being taught to question their gender identity. Some even report discovering their children are using new names and pronouns while at school without their knowledge or consent. Yet these fears are frequently dismissed as reactionary parents trading in anecdotes and panic. Nothing to see here, has been the message from schools and campaigning organisations alike. Until now.

A report from Policy Exchange reveals the extent to which gender ideology is being promoted in schools and the shocking ways in which this puts children at risk. In Asleep at the Wheel: An Examination of Gender and Safeguarding in Schools, Lottie Moore uses hard data to expose the true proportion of schools that are leading children down the transgender path.

More than a quarter of schools allow male pupils to use the same toilets as girls

This research shows that an astonishing four in ten secondary schools now operate a policy of gender self-identification. This means that teachers ignore all records of a child’s biological sex and instead treat pupils as whatever gender they declare themselves to be. The safeguarding risks of this approach should be immediately obvious. Policy Exchange has the statistics: at least 28 per cent of secondary schools are not maintaining single sex toilets, and 19 per cent are not maintaining single-sex changing rooms.

In other words, at a time when concern about sexual harassment among teenagers is rife, more than a quarter of schools allow male pupils to use the same toilets as girls. And almost one third of schools now teach pupils that a person who self-identifies as a man or a woman should be treated as a man or woman in all circumstances, even if this does not match their biological sex. Presumably such moral lessons hold true when that person seeks to undress next to you in a changing room. Shockingly, girls are being instructed not to have boundaries or to expect privacy when it comes to their own bodies.

Sadly, it is all too easy to see how this situation has arisen. When faced with seemingly competing demands to safeguard pupils and to adhere to a contested gender ideology, headteachers and school governing bodies have taken the politically easier option and decided to appease transgender activists. But this may leave schools in breach of the law.

Take another shocking statistic the research has uncovered: only 28 per cent of secondary schools are reliably informing parents as soon as a child discloses feelings of gender distress. They allow pupils to adopt a new gender while at school and conspire to keep this from their parents. It is difficult to square this practice with Article 8 of the Human Rights Act which sets out the ‘right to respect for private and family life’.

Schools argue they are having to deal with a growing number of children presenting with gender distress and have, not unreasonably, sought help from external agencies on how best to handle this new problem. But this overlooks the role schools have played in promoting gender distress in the first place. Asleep at the Wheel reveals that 25 per cent of schools are teaching children that some people ‘may be born in the wrong body’ and almost three quarters of schools teach that people have a gender identity that may be different from their biological sex.

This makes it abundantly clear that it is not one or two activist teachers promoting regressive stereotypes over biological facts but that such ‘lessons’ are being repeated in the overwhelming majority of schools. This is in contravention of Sections 406 and 407 of the Education Act 1996 which dictates that schools have a legal obligation to be politically impartial and that where political viewpoints are raised, children should be offered a balanced presentation of opposing views.

In attempting to address a problem at least partially of their own making, schools end up exacerbating confusion about gender still further. More than two-thirds of secondary schools insist that all pupils affirm a gender-distressed child’s new identity, presumably by using their preferred name and pronouns. In this way, children are compelled to speak untruths, and schools yet again fall foul of the Human Rights Act 1998, which protects the right to freedom of expression.

The Policy Exchange research on gender and safeguarding is to be welcomed. Never again will activist teachers or political campaigners be able to deny the reality of what is happening within our schools. In an important foreword to the report, Labour’s Rosie Duffield is clear:

‘This government has failed children by allowing partisan beliefs to become entrenched within the education system. Meanwhile, the Opposition has failed to pull them up on it.’

This cannot be allowed to continue.

Amsterdam’s lazy campaign against British tourists

Amsterdam has launched a campaign telling rowdy Brits to stay away. Men between the age of 18 and 35 are being targeted with videos showing what happens to those who overindulge. Brits who search online for terms like ‘stag do’, ‘cheap Amsterdam accommodation’ and ‘pub crawl Amsterdam’ will be served with the warning adverts featuring tourists being locked up or hospitalised.

To put it in wrestling terms, we’ve well and truly become the ‘heels’ of Europe. Brexit, it seems, has catalysed the unfair ‘bad boy Brit’ persona of a sometimes sluggish, mostly uncultured and drunken nation which urinates and swears its way across the continent while ordering beige grub in slow and shouty English. Amsterdam welcomes 20 million tourists per year and has long been perceived as a haven of sex, drugs and biking – sometimes in that order. But now, it appears, the city’s authorities want to put off Brits. Is this really fair?

Amsterdam’s ‘Stay Away’ campaign plays into the unruly Brit stereotype

The background to the ‘Stay Away’ campaign is that Amsterdam sort of wants to change its reputation, but sort of doesn’t – and young Brits have now found themselves in the middle of these political contortions.

The city’s mayor Femke Halsema, who has been in the post since April 2018, is at the heart of this muddle. Halsema, a former leader of the green left-wing GroenLinks party and the city’s first female mayor, has rightfully warned that some Amsterdammers feel estranged from their own city as the commercialisation of prostitution and soft drugs has created a hedonistic headache.

Many residents are understandably tired of the ugliness and anti-social behaviour. The city’s authorities reacted late last year by launching a ‘Visitor Economy 2035’ plan, a package of measures with the overarching aim of changing Amsterdam’s international reputation. The ‘Stay Away’ campaign – which will initially target British men before being rolled out more widely – is part of this initiative.

But the trouble is that Halsema doesn’t exactly want to get rid of all the vices blighting one of Europe’s most picturesque capitals. Instead, it seems she wants to move the problem elsewhere: when it comes to prostitution, this means an ‘erotic centre’ somewhere outside of Amsterdam’s historic capital. But it’s OK because, to use Halsema’s own word, the new red light district will be ‘chic’.

Halsema is clear that she doesn’t want to ‘criminalise prostitution’. ‘It’s very important women and trans workers can do their work in safe conditions and in accordance to human rights,’ she says. Halsema also wants cannabis to be fully legalised. But where does this sit with the attempt to clean up Amsterdam’s image? It’s hard to know.

In the absence of any clear approach to whether or not the city wants to sort itself out, a spot of Brit bashing seems like a convenient option. But this lazy targeting of Brits is not helpful. It also risks having serious and dangerous consequences for Brits abroad. You only have to look back at what happened last May during the Champions League Final when Liverpool faced off against Real Madrid in Paris. Because of ticketing problems and stewardship issues, thousands of fans found themselves stuck outside of the Stade de France in cramped conditions where the police decided to treat them with a liberal dosing of tear gas and pepper spray. The heavy-handed tactics were initially justified by the French authorities on the basis that Liverpool fans were being disorderly. In short, the suggestion was that the Brits were up to their old tricks again and basically deserved what they got – even if they were, in fact, just innocent football fans.

After a backlash from supporters, journalists and British politicians, Uefa eventually saw sense: in February, it published its investigation into what became known as the ‘Champions League Chaos’. The review admitted that Liverpool and Real Madrid fans could have died, criticised French police and ministers and conceded that Uefa had ‘primary responsibility’ for the failures around the event. The worrying thing is that it look a concerted effort for this horrifying incident to be investigated in the first place. Seemingly, if the French authorities had their way, they could have just blamed the Brits.

Amsterdam’s ‘Stay Away’ campaign plays into the unruly Brit stereotype, effectively making the continent a more dangerous place for sons, brothers and fathers who are continually paying for the sins of the hooliganism of the 1980s – a decade most weren’t even born into.

This latest campaign by the authorities in Amsterdam certainly puts the past comments of the city’s ex-mayor, Eberhard van der Laan, into perspective. Back in 2014, he quoted Liverpool’s famous tune to his then London counterpart Boris Johnson. Talking about Brit tourists, he said:

‘They don’t wear a coat as they slalom through the red light district… they sing ‘You’ll never walk alone’. They are dressed as rabbits or priests and sometimes they are not dressed at all.’

The truth is that most Brits who go to Amsterdam do so to have a good time and manage to stay out of trouble. But this targeting of tourists from the UK seems to ignore this fact – and risks doing more harm than good.

Rishi Sunak now sees a future for fossil fuels in Britain

The location of Rishi Sunak and Grant Shapps’s net zero relaunch today shows there has been a change of emphasis since the PM set up the Department for Energy Security and Climate Change last autumn.

One suspects a bit of ideology creeping in: fossil fuels have become a great bogeyman, and nothing will make them acceptable

Whereas Boris Johnson might have sought to make such an announcement at a wind farm or solar farm, today’s relaunch took place at Culham in Oxfordshire, the site of Britain’s nuclear fusion research facility. Fusion is the holy grail of carbon-free energy which even enthusiasts admit is decades away from being commercialised, if it can be at all. But it is a hint that the government is no longer going to try to power Britain with wind and solar energy alone. A competition to pick out the most promising modular nuclear reactor designs – for further funding and development – is one of the strands of today’s announcements.

The most eye-catching initiative is carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). In his recent budget Jeremy Hunt announced a remarkable £20 billion of investment in CCUS projects. Now we learn that eight ‘clusters’ of projects are planned (although they won’t include Drax, the woodchip-burning power station in South Yorkshire whose shares have dived this morning in response to the news it has lost out on government backing).

Compared with the £240 million the government has made available to develop its ‘hydrogen economy’, this is a vast sum. Today’s document, ‘Powering Up Britain’, doesn’t quite spell it out, but the quest for CCUS signals that the government has changed its mind and now sees a future for fossil fuels. The whole point of CCUS, after all, is to suck out from the air carbon dioxide which has been produced by burning fossil fuels. As things stand, the government remains committed to removing all fossil fuels from electricity production by 2035, banning petrol and diesel cars, as well as new gas boilers, by the same date and pushing for existing gas boilers to be replaced by electric heat pumps at the rate of 600,000 a year. But what if we had a CCUS industry that was removing carbon from the atmosphere at the same rate it was being pumped in? The objections to burning fossil fuels would theoretically disappear. We could, say, continue to use gas power plants to back up intermittent wind and solar – and eliminate the need to find some way of storing vast amounts of energy.

That is not, however, how many green campaigners see it. Anticipating today’s announcement, 700 scientists and campaigners have written to Sunak demanding that no new oil and gas licences be granted. They complain that CCUS is no solution because it has ‘yet to be proved at scale’. They are right on that point – although the same is true of numerous other technologies which have been floated as possible ways of getting to net zero, and which are regularly advocated by some of the signatories. One suspects a bit of ideology creeping in: fossil fuels have become a great bogeyman, and nothing will make them acceptable.

The truth is, if the world is going to get anywhere close to net zero, CCUS will have to be used – because the process emissions from steel-making, cement-making, fertilizer-manufacturing and agriculture are going to be extremely difficult to address. Yet the government is taking an enormous gamble with its £20 billion. A decade ago, David Cameron launched a similar initiative, involving the investment of a more modest £1 billion in a CCUS demonstration plant. But in 2015 the scheme was abandoned, shortly before the expected announcement of who had won the bid. The government on that occasion came to the conclusion that CCUS was too much of a unicorn to take a risk with. Question is: what has changed now?

Joining CPTPP shows Britain is finally seizing the benefits of Brexit

Even the most ardent Brexiteers would likely admit that the UK has been slow to embrace one of the biggest benefits of leaving the European Union: the quick and nimble pursuit of trade deals. There are understandable reasons for the delay. It made sense for trade secretaries to start with the bi-lateral deals which could be copy-pasted from the arrangements we had in the EU. The first bespoke deal with Australia took time (albeit perhaps didn’t need so many concessions) as it was intended to be a framework that could be used to strike future deals with new countries.

But the UK’s biggest trade win to date may be just around the corner. It is expected that the UK’s accession into the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) will be formally announced tomorrow. We don’t know the details of what has been negotiated yet, so it’s impossible to say just now the extent to which the UK’s new membership will move the trade dial. But in its short, five-year run, CPTPP has developed a strong reputation for being one of the more liberal, flexible trade blocs. Even without knowing all the details of what the UK has secured, the basic framework of CPTPP suggests there is a lot to benefit from, especially in the sectors where Britain holds an advantage.

Perhaps most importantly it isn’t who is brought into the trade bloc, but who is kept out

The Indo-Pacific trade bloc was founded in 2018 with eleven members, including Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Canada and Mexico. The countries together make up a $10 trillion market, of which the UK is expected to become the first non-founding country to gain admittance. The bloc was created with small and medium-size businesses in mind, in a bid to expand their export markets. This means its benefits include what government officials describe as ‘old school’ trade perks: the removal of tariffs and quotas, making it cheaper and easier to export goods. Whatever the UK has negotiated, British businesses can be fairly certain they’re about to get better access to markets on the other side of the world, while British customers will benefit from lower prices when they import products from just over a dozen countries.

But it is in the digital sectors, including financial services and e-commerce, where Britain may really thrive. In a paper published late last year, looking at the benefits and challenges to the UK joining CPTPP, Professor David Collins from City Law School details the more flexible nature of the CPTPP when it comes to financial services.

Not only is CPTPP compatible with UK cross-border trade as it currently exists now, it is also less restrictive, allowing for member states to adopt discretionary measures to ‘maintain the integrity and stability’ of their systems. The report estimates that the long-term benefits for the UK’s financial services sector having better access to these eleven countries will exceed £3 billion. The report also highlights how CPTPP compliments the UK’s thriving e-commerce industry: unlike the EU’s rigid and unrelenting commitment to GDPR, CPTPP takes a more liberal approach, by keeping more data-sharing decisions within the remit of individual member states.

There have been setbacks in negotiating this new partnership: right before the Budget earlier this month it was reported that the deal was delayed due to disputes over access to the UK’s agricultural market, particularly concerning meat exports. Tomorrow we’re set to discover how these disputes have been settled. This was always cited as one of the drawbacks of Britain joining CPTPP: to sign up after the framework has been created means far less room to negotiate. But even without these details, the framework established by the founding members creates a lot of opportunities across the sectors Britain cares about most.

These economic opportunities don’t exist in a vacuum. The hope is that their knock-on effect will aid Britain’s longer-term economic strategy. Ministers are resigned to the fact that, right now, it is politically impossible to secure a bi-lateral trade deal with the United States, given the uproar (however misplaced) that results over food standards and healthcare provisions. But if the US were to reconsider joining CPTPP (the country was set to do so under President Obama, then President Trump pulled out of the deal), the UK and US could liberalise their trading relationship through a third-party bloc.

But perhaps most importantly it isn’t who is brought into the trade bloc, but who is kept out. Both China and the UK applied for CPTPP membership within three months of each other back in 2021. China’s membership was heavily debated and delayed, but the bloc’s unanimous decision to admit the UK presumably gives us a veto on any new member joining – de facto power to keep China out of the bloc.

As the West becomes increasingly worried about its dependence on authoritarian regimes – and more focused on ‘decoupling’ from China’s economic power and Russia’s energy – this veto power could turn out to be the most important aspect of Britain’s soon-to-be-announced membership of CPTPP.

Why Humza Yousaf faces a nightmare start as First Leader

The Yousaf terror has begun and already the new regime isn’t off to a great start. Day one saw his calls for another referendum brushed aside by No. 10. Day two brought the refusals of Kate Forbes and Ivan McKee to serve in his government. And now on day three, the Privileges Committee have handed Margaret Ferrier a 30-day suspension from parliament, potentially triggering a by-election in her seat of Rutherglen and Hamilton West (majority: 5,230). What joy will day four bring?

Ferrier of course is the hapless halfwit who admitted travelling down to London after developing Covid symptoms. Not only did the MP fail to stay at home to prevent potentially spending the disease back in 2020, she also decided to speak in Parliament, and then decided to travel back to Scotland on the train after receiving a positive Covid test. At the time, she was required to self-isolate under the law – talk about the brightest and best. Last year she pleaded guilty to wilfully exposing people ‘to the risk of infection, illness and death’ and sentenced to 270 hours of community service.

Ferrier has been suspended from the SNP for more than two years but has only today been slapped with the 30-day suspension from the House of Commons, following a lengthy investigation. Under the rules, any suspension of 10 days or more can trigger the Recall of MPs Act which means that if 10 per cent of an MP’s constituents sign a petition, a by-election shall be held. MPs will now vote on whether to back the suspension; if they do, Ms Ferrier can appeal the ruling or resign. In the case of the latter a by-election would be held which she would not fight. Scottish Labour will be smacking their lips at the prospect of such a fight, with Rutherglen a key target in the next election.

The other element to all this is the breakdown of the votes by the Privileges Committee: though the decision passed with a majority, the Tory vote was split for the first time. Three Conservatives – Sir Charles Walker, Sir Bernard Jenkin and Alberto Costa – voted against the decision. All three are coincidentally sitting on the panel which is judging whether Boris Johnson lied to the House. The trio suggested reducing Ferrier’s sanction to nine sitting days which is under the recall threshold. That is a verdict which Johnson would be delighted to receive as it would mean he would avoid a likely by-election.

Is that a sign of things to come when the committee rules on Johnson’s fate? Mr S looks forward to finding out…

The Tories should think again on targeting Netflix

If you want to understand the curious attitude of our government towards media freedom, look at two provisions in the draft Media Bill, published yesterday. One is refreshingly liberal; the other curmudgeonly and authoritarian.

First, the good news. The Bill reads the last rites over the Leveson Report of 2012. A worrying document embodying lofty patrician contempt for the popular press, this had called for highly intrusive controls over it. This included closer supervision of what journalists were allowed to do and editors to publish, an increase in damages for breach of privacy and a noticeable tightening of the dead hand of data protection on newspaper information-gathering. And, to cap it off, all papers worth the name should submit to a semi-official regulator with expansive powers to write a code of practice, fine newspapers for breaking it (even if they had not acted illegally) and impose corrections and apologies. True, Leveson reluctantly stopped short of demanding legal compulsion, but he called for none-too-subtle pressure in the shape of a punitive legal costs rule for any papers which failed to sign up (essentially making them pay the court costs of anyone who sued them, even if the claim failed).

The latter was actually enacted in law, and an officially approved regulator called Impress set up, though the heavyweight newspapers pointedly – and rightly – boycotted it, preferring the more independent Ipso. (Impress still exists, albeit mostly regulating local titles and a few small, predominantly left-wing outlets.) Thankfully the costs law was never brought into force; and now, despite periodical calls to activate it, the Media Act repeals it.

The idea of extending Ofcom’s writ as a kind of Ministry of Medical Truth to cover any large organisation beaming material to the UK is not reassuring

This not only removes a sword of Damocles hanging over the national press, but shows a welcome shift in opinion towards leaving newspapers alone and subjecting any wrongdoing to the ordinary law. True, organisations such as Hacked Off have seen this as a government bribe to the press. But since the Guardian and the Independent objected to the law on court costs just as vehemently as the Daily Mail did, and even Labour are happy with the repeal (despite their previous regular calls for it to be put into effect) there is a strong whiff of humbug here.

So far so good. But now for the bad news: having freed the written word, the Media Bill proposes a massive increase in control over the moving image. The problem, as the government sees it, is that while traditional broadcasters such as the BBC and ITV are heavily regulated by Ofcom in what they can do, say and promote, global pick-and-mix outfits like Disney+ and Netflix – which pick up millions in subscriptions that used to go to the BBC in licence fees – are not. This will not do at all, said the culture, media and sport minister Lucy Frazer, in a slightly scandalised press release. We must, she said, level the playing field, corral the foreign internet giants, and regulate their UK output in much the same way as we regulate traditional broadcast channels. This is, supposedly, to make viewers feel safe and prevent them suffering ‘harm’ from such things as ‘misleading health information’ (one of the government’s examples).

This should worry us. For one thing, it’s all very well in the rarefied air of the DCMS to talk of our world-class broadcasting, the assurance of quality its close regulation gives UK viewers, and the need to assure them that they will get a similar guarantee if they watch outliers such as Netflix instead. But back on earth, if the public are turning away in droves from our own highly regulated offerings and choosing unregulated foreign services, this might suggest that the latter are doing something right. It might even be an argument for decreasing regulation of our own broadcasters, rather than increasing Ofcom’s grip on foreign providers.

Moreover, the mention of ‘misleading health claims’ as something that needs an Ofcom crackdown should prick up some ears. Ofcom’s record here has, to say the least, not been spotless. During the pandemic, for example, it used exactly this line to enforce a pretty heavy-handed suppression of anything other than the official line on mask wearing, or Covid jabs. Indeed, it fined stations which allowed the wackier conspiracy theorists airtime at all. Quite apart from all the other restrictions proposed, the idea of extending Ofcom’s writ as a kind of Ministry of Medical Truth to cover any large organisation beaming material to the UK is not reassuring.

More to the point (however administratively tidy it might look), there is also a fundamental problem with demanding similar treatment for programmes available on demand as for traditional television. Turn on a BBC or ITV channel, and one programme automatically shades into another through the evening. In this case, there is some argument for rules to protect a family from finding itself unexpectedly watching, say, a horror film before the watershed, or content that is distressing or offensive. But not so with on-demand services such as Amazon Prime Video or Netflix: there, you choose to watch individual programmes, rather like picking out a book to read. And unless we now take the seriously demeaning attitude that viewers simply cannot be trusted to choose what is good for them, the case for regulation becomes as tenuous as that for regulating what we are allowed to read.

In short, regulating on-demand viewing is not so much a recipe for excellent television as an ego-trip for Ofcom, a censors’ charter (except for the computer-savvy who can use a VPN to bypass Ofcom entirely), and a message to British viewers that they can’t be trusted to exercise proper judgment over what they choose to watch. Frazer is generally a good culture minister; her final burial of Leveson bodes well. But here, she needs to think again.

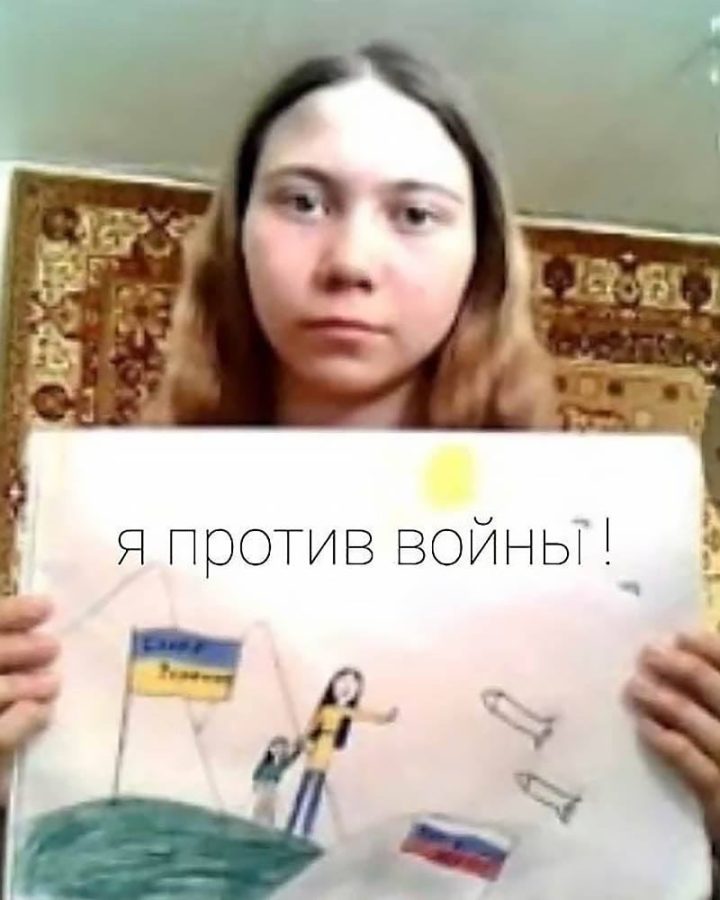

Putin’s crackdown on Russia’s school children

In Russia, nowhere – and no one – is safe from the insidious reach of Putin’s war in Ukraine. In April 2022, during a school art class, twelve-year-old Masha Moskaleva drew a picture of a Russian and Ukrainian flag with missiles flying at a mother and child. Inside the flags, she had written ‘Glory to Ukraine’ and ‘No to War’.

Masha’s art teacher saw her drawing and called in the head teacher who then called the police. Officers interrogated her and her classmates, but Masha managed to slip away after giving them a false name. The following day, as her father, Alexei, was picking her up from school, the two were apprehended by police and taken for questioning.

Тhis shows how the state’s propaganda machine is working its way into the country’s schools

During his interrogation, Alexei was accused of ‘discrediting the army’ over posts on social media which he denies writing. He was charged, fined 32,000 RUB (£340) and a criminal case was opened against him. Masha, meanwhile, was interrogated by the FSB and, traumatised by the incident, refused to go back to school.

Fast forward to 30 December and Masha and her single father were woken up by an FSB raid on their home. The security services ransacked the house, took Alexei into custody and forcefully removed Masha to an orphanage. Alexei was accused of neglecting his parental duties towards his daughter, and even though both were briefly reunited, since the beginning of March the two have not been allowed any contact.

On Tuesday, Alexei Moskalev was sentenced to two years in prison for repeatedly ‘discrediting’ the Russian army. However, his legal team disputes the conviction, arguing, almost certainly correctly, that it is a concocted screen to punish him for the actions of his daughter. Moskalev was, it turns out, sentenced in absentia, after it was revealed (following the verdict) that he had actually fled house arrest on 27 March. After several days on the run, Moskalev was reportedly captured and detained in Minsk, Belarus, in the early hours of 30 March.

Masha’s whereabouts are currently also unknown, after the orphanage the authorities claim she is being housed in have reportedly told supporters of the pair that she is currently not there. A petition calling for Masha to be returned to her father has, so far, gained nearly 145,000 signatures. Meanwhile, a trial aimed at depriving Alexei of custody of Masha is due to be heard on 6 April.

The fate that has befallen this father and daughter over the past year or so demonstrates just how Kafka-esque Russia has now become. In what free country would a teacher call the police, or the security services interrogate a twelve-year-old girl, over a drawing? Paranoia and jingoism has seemingly spread through all elements of society – as the Kremlin hoped it might.

Masha is not the only child in Russia for whom school has ceased to become a safe space from the war. Stories are beginning to appear on Russian social media and in the independent press of Russian teachers doling out excessively harsh discipline or, as in Masha’s case, calling the police over insignificant or minor misdemeanours.

One video doing the rounds on social media at the beginning of the month shows a boy, said to be around fifteen years old, being told off by his teacher for being late to school. The day in question is 23 February, celebrated in Russia as ‘Defender of the Fatherland Day’, appropriated by the state this year, unsurprisingly, as a celebration of all those fighting in Ukraine.

The teacher’s reaction to her pupil’s tardiness is shocking in its harshness: she calls the boy a ‘traitor’ for being late, she kicks him out of her class, says she’s already called his mother. He’s a ‘bastard’ and ‘nothing to her’; traitors like him get it ‘right here in the temple’, she says, prodding him in the side of the head.

Some of these incidents, can of course, be put down to jobsworthy teachers. Others could, reasonably, be accounted for by teachers terrified that they might be held responsible for the actions of their pupils; better to report them than face consequences themselves. If so, this shows how the state’s propaganda machine is working its way into the country’s schools.

Over the last month, new desks have been rolled out in Russia’s schools. Wrapped in green, the desks bear photographs of soldiers killed in Ukraine along with their biographies. Championed by the ‘United Russia’ party, these macabre work stations have been branded ‘Heroes’ desks’ – only those children who come top of the class will be afforded the ‘honour’ of sitting at them. At the unveiling of one such desk at a school in Irkutsk, two children fainted, reportedly ‘affected’ by the tears of the dead soldiers’ relatives who attended the ceremony.

Masha Moskaleva will, no doubt, not be the last Russian child to fall victim to teachers more concerned with upholding state propaganda than safeguarding their students. As the Kremlin knows only too well, the most effective way to uphold an oppressive regime is to manipulate the minds of the next generation: to that end, teachers are their most effective weapon.

The new age of sleeper trains

It’s a fabulous combination: travelling by train and sleeping. And the good news is that the concept of sleeper trains is being revived. The bad news is that, like trams and trolleybuses, a wonderful form of travel was allowed to decline in the first place.

The first sleeper carriages – as opposed to trains you happened to fall asleep on – were introduced in the US in the late 1830s, but these provided little more than hard wooden benches. It was George Pullman who built the first luxury sleeper coaches when he founded his eponymous company in 1867. America, with its vast expanses and a newly opened transcontinental line, was fertile territory, and Pullman coaches were soon being attached to long-distance trains. They were staffed by black attendants who, bizarrely, were all instructed to say their name was George.

In Europe, the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits built up a large network of overnight services in the final quarter of the 19th century, with famous names such as Orient Express. In the UK, sleeper services were similarly established, mostly running between London and places as diverse as Milford Haven. Just two survive: the Night Riviera linking Paddington with Cornwall; and the Caledonian Sleeper between Euston and various Scottish destinations, which has just been renationalised by the Scottish government.

As a child, I managed to persuade my mother to take the sleeper train down to the Côte d’Azur by making spurious claims of car-sickness. The service started at Calais Maritime, next to the ferry, and after meandering through northern France and around Paris, we would enjoy an onboard meal of consommé and steak frites. Delicious as it was, waking up to a view of the Mediterranean nestled between the red rocks of the Estérel mountains while breakfasting on croissants delivered to the compartment was even better.

Then it was my turn to show my kids the wonders of overnight train travel. The accommodation on the ski train from Paris to the French Alps was pretty basic as the carriages had probably survived the second world war, but there was often an onboard disco which made up for the nasty sandwiches. Fifteen years ago I even managed a trip to Vienna on one of the last services of the Orient Express, which by then had degenerated into a meagre cut-back service with so few passengers that a murder would have been all but impossible.