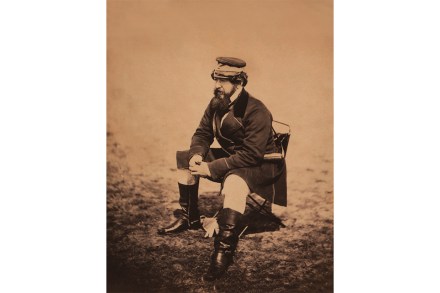

The Crimean War spelt the end of hymns to heroism and glory

Leo Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer in the defence of the great Russian naval base of Sevastopol against British and French invaders in the middle of the 19th century. The first of his three short stories, collected as Sevastopol Sketches, came out as the siege was still in progress. In it he spelled out as no writer had done before the way people died in shattered trenches, their bodies shredded by shell fire and left to rot in the mud; or in filthy, overcrowded hospitals, where overwhelmed doctors hacked off limbs without anaesthetic. He wrote not about the generals but about the ordinary soldiers, the men and women