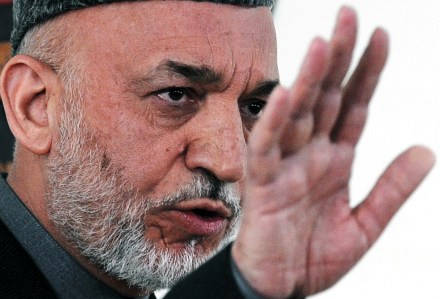

President Petraeus Watch

Not much news came out of Washington last week which doubtless explains why my old chum Toby Harnden used his Telegraph column to chew over the Petraeus 2012 “speculation” one more time. This won’t be the last we hear of this, I assure you. Alas, as Toby laments, the good General stubbornly refuses to play along: The problem is that Petraeus appears to have no desire to be commander-in-chief. His denials of any political ambition have come close to the famous statement by General William Sherman. The former American Civil War commander, rejecting the possibility of running for president in 1884 by stating: “I will not accept if nominated and