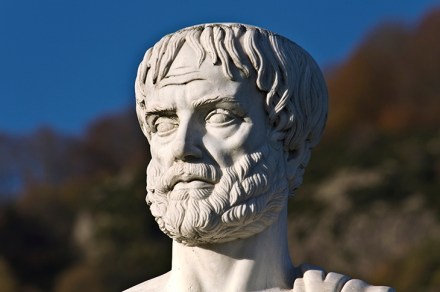

For the ancient Greeks, the only point in taking part was to win

The England team reached the final of the rugby world cup in Japan but they lost. As athletes, they knew that was failure. So did the ancient Greeks: only the winner was worth a prize. The poet Pindar (c. 518-440 bc) explored the consequences of this mentality. In one of his commissioned poems hymning victorious athletes, he described how Aristomenes defeated three wrestlers en route to winning the prize (a bay laurel wreath) at the Pythian Games at Delphi. Of those losers, Pindar said: ‘They were left no happy homecoming. As they ran back to their mothers they heard no joyous laughter to give them delight: no, they slunk furtively