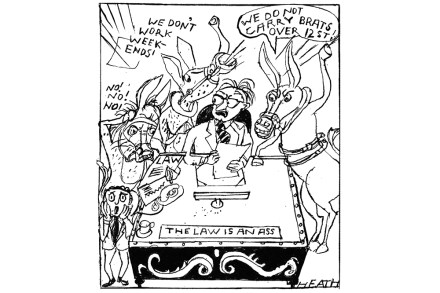

The evolution of the political animal

Most of our politicians themselves are not obedient, kindly and loyal. Similarities between candidates and their faithful cat or dog are few – but as trolls now deter supportive spouses and photogenic children from saccharine election leaflet photos, pets are increasingly becoming familial proxies. When Nigel Farage does a TikTok about his dogs Pebble and Baxter, thousands comment approvingly. But finding a family photo of the Reform UK leader is nearly impossible. And that, says Farage and many like him, is entirely deliberate. Political animals are not new. Caligula threatened to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul. Cardinal Wolsey’s cat is immortalised in a bronze statue in Ipswich. In the 20th century, cats assuaged Winston Churchill’s