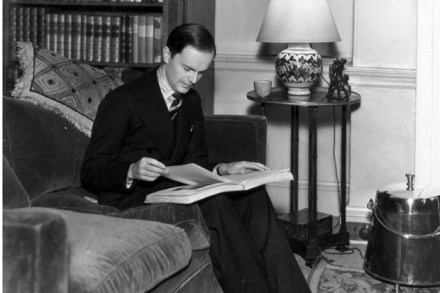

Arthur Jeffress: bright young person of the post-war art scene

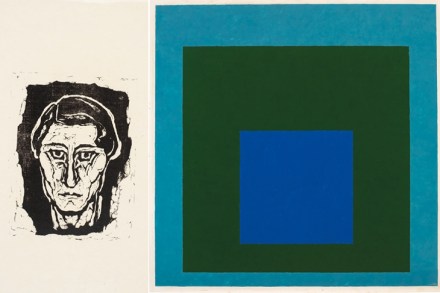

The name Arthur Jeffress may not conjure many associations for those not familiar with the London post-war art world, but this wayward, flamboyant, controversial connoisseur and patron who left much of his ‘small but subversive’ collection to the Tate and the Southampton Art Gallery after his death in 1961 certainly deserves his footnote in history. ‘Small but subversive’ could describe the man as well as his collection: his fabulous wealth, inherited from Virginian tobacco plantation-owning ancestry, coupled with his rampant homosexuality, shaped a life of compulsive and conspicuous extravagance, in which art and sex vied with one another for supremacy against the backdrop of Belgravia and a palazzo just off