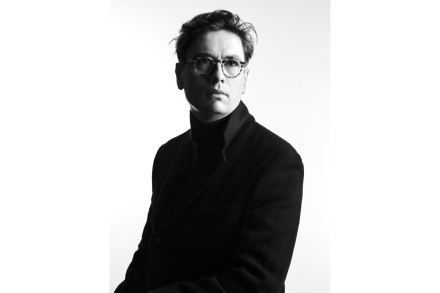

Brian Cox’s Bach has to be heading for Broadway

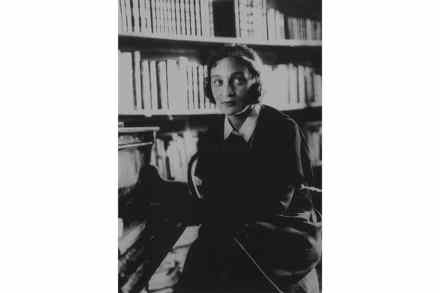

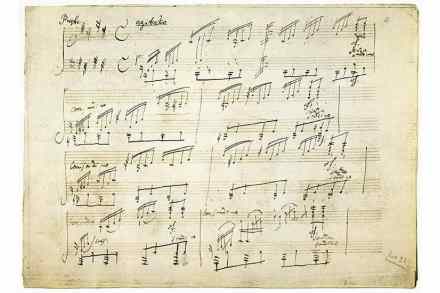

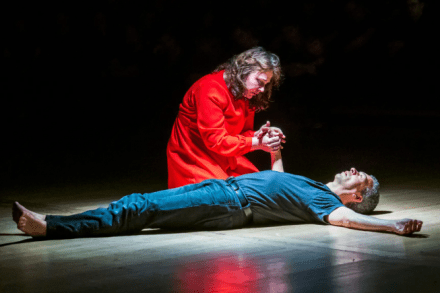

The Score is a fine example of meat-and-potatoes theatre. Simple plotting, big characters, terrific speeches and a happy ending. The protagonist, J.S. Bach, receives a mysterious summons from Frederick the Great of Prussia. The long first act takes us through Bach’s professional woes and his physical infirmities. His weak vision is being treated by an English oculist, John Taylor, who tours Europe in a scarlet coach decorated with eyes. For unexplained reasons, Taylor decides to taste Bach’s urine, which is excessively sugary – a symptom of diabetes. When Bach reaches Frederick’s court in Potsdam he finds the atmosphere oppressive and alienating. Enter Voltaire. ‘Prussia is not a state in possession