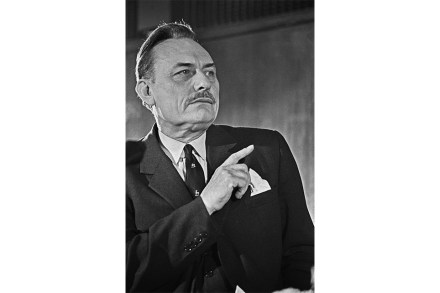

Few rulers can have rejoiced in a less appropriate sobriquet than Augustus the Strong

Augustus the Strong (1670-1733), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, is often labelled one of the worst monarchs in European history. His reign is billed by Tim Blanning’s publishers as ‘a study in failed statecraft, showing how a ruler can shape history as much by incompetence as brilliance’. Yet this thorough and often hilarious study of Augustus’s life and times reveals these harsh headline words to be exaggerated. Indeed the man comes across as quite a good egg, as much sinned against as sinning. With disarming immodesty, Augustus described himself as: A lively fellow, carefree, showing from a young age that he was blessed with a strong body, a