A book that’s inspired by a movie (for a change)

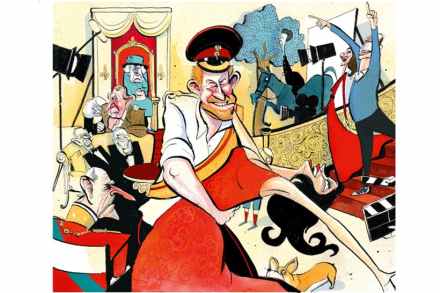

Books become films every day of the week; more rarely does someone feel inspired to write a book after seeing a film. Peter Conradi’s Hot Dogs And Cocktails tells the story of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth’s visit to North America in the summer of 1939 and specifically the couple of days they spent at President Roosevelt’s country retreat at Hyde Park on Hudson. In the film of that name, Bill Murray played FDR with a characteristic twinkle in his eye, and the story was fleshed out with a did-they-or-didn’t-they illicit romance with his distant cousin, played by Laura Linney. For reasons of professional integrity Conradi can’t play quite