Wells of silence

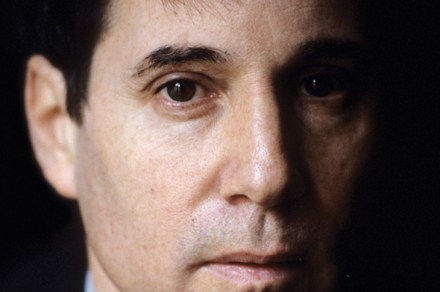

Someone has gone to a lot of trouble choosing the jacket cover of Robert Hilburn’s authorised biography of Paul Simon (reproduced right). It is both flattering and enigmatic, which is entirely appropriate, given its contents. Half of Simon’s features are lost in a shadow cast across his face — again, entirely appropriate, as Simon wrestled with Hilburn for more than two years, determined to ensure his true self remain partly or wholly in the shadows. One can’t help wondering why thesinger-songwriter even agreed to sit for what the jacket copy assures us was 100 hours of interviews; or, indeed, what happened to the other 99. For Simon’s voice barely rises