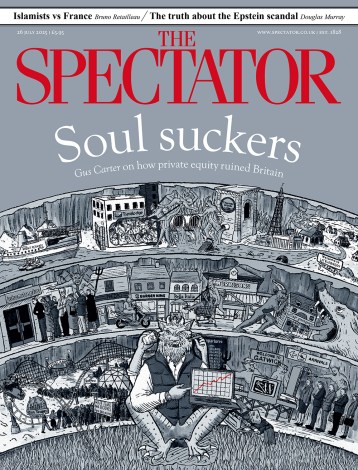

Samuel Beckett walks into a nail bar

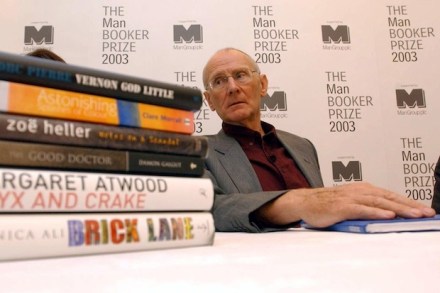

It isn’t very often that a writer’s work is so striking that you can remember exactly where and when you were when you first read it. I was in a parked car in a hilly suburb of Cardiff last summer when I first became aware of George Saunders, from reading a speech he’d addressed to his American students printed in that day’s edition of the International Herald Tribune. Within the first two or three lines it was evident that this was someone quite out of the ordinary, someone of unusual intelligence, curiosity and compassion. This speech — an exhortation to be kind — is wonderful. And so are these short