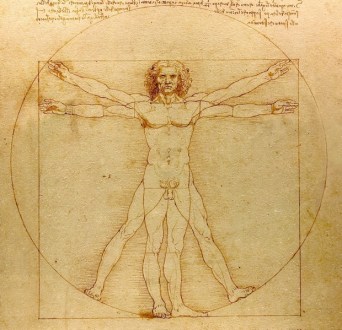

Biblical art, like Christianity, is always renewing itself

This sign adorns a local church in Harlesden. I suppose it could be called a Pop Annunciation. Who says religious art is stuck in the past? Then again, it is a perennial – and fascinating – question in Christian art: how much contemporary life to include in biblical scenes. For centuries artists have shocked the public by including ordinary-looking young beauties as Mary, ordinary working blokes as shepherds or apostles. Caravaggio is a good example, but even before him nativity scenes were transposed to Tuscan landscapes. In fact the first realistic landscapes in Western art were posing as biblical backdrops. The shock was rehashed by the Pre-Rapahelites, whose sacred scenes featured