Are these performances of the Bach cantatas the best on record?

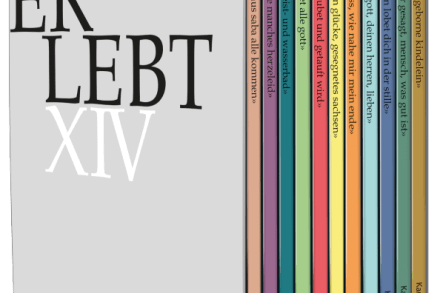

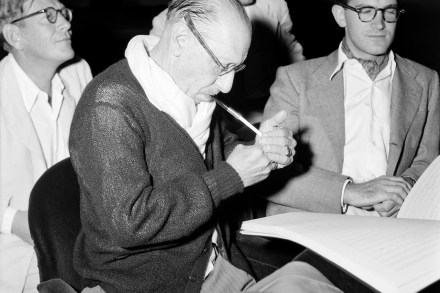

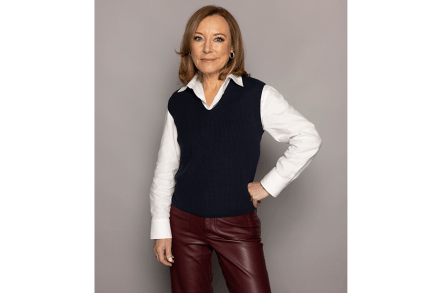

Three projects shedding light on the sacred music of J.S. Bach are nearing completion. The first consists of an epic 25-year project to record all the composer’s vocal works – passions, masses, motets and more than 200-odd cantatas – in electrifying performances supplemented by lectures and workshops. At the helm is a Swiss choral conductor renowned for his improvisatory skills – and surely the only baroque specialist to have played Sidney Bechet on a chamber organ. The second project is a guide to Bach’s church cantatas tailored at ‘cultural Christians’; that is, music lovers intrigued but intimidated by their Lutheran theology, unsure how to approach this treasure trove of, at