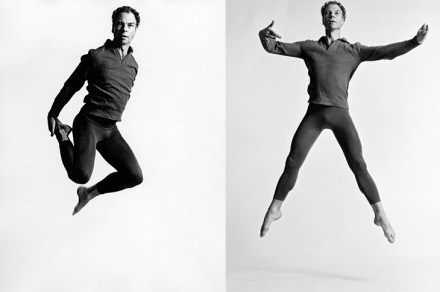

Dying of the light

It’s a comfort that the creation of a new ballet inspired by French court entertainment can still happen in the amnesiac ballet country that Britain has become. The idea of making a modern-day meditation on the first ballet — Louis XIV’s 12-hour epic Le Ballet de la nuit (1653) — is as intellectual as Wayne McGregor’s roping in of cognitive science as source material. It faces many of the same traps when it comes to capturing that elusive necessity: theatricality. Only David Bintley could do this, deploying his artistic authority as the 20-year director of Birmingham Royal Ballet as any French despot would. The scheme’s theatricality is innate. Le Ballet