Monty Don, Kirstie Allsopp and Bear Grylls – we get the TV shows we deserve

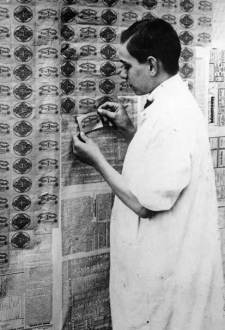

We’re now on day three of the Chelsea Flower Show, and this year the BBC have taken their coverage to the max. As well as the quotidian hourly slot with Monty Don, Joe Swift and newcomer Sophie Raworth, in the week preceding the show we were also treated to the daily Countdown to Chelsea. What is it that makes the public so interested in gardening that we are willing to watch so much of it? Gardening is, for the most part, about scrabbling around in the mud and digging up weeds. But that’s the point. If this were a country where the majority of people earned their keep by growing plants