How ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ plays tricks with the mind

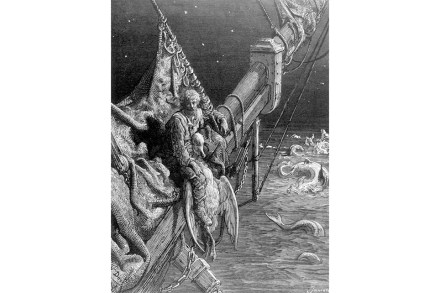

I’ve just returned from five days in the Lake District, attending the biennial ‘Friends of Coleridge’ conference in Grasmere. All the other attendees were seasoned Coleridge scholars, but I was a newbie. The reason for my going was the fact that I’m engaged in a project that has at times felt something of a lonesome road and indeed an albatross: to write a book about Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. The poem comes to us with a vast undertow of explicit and implicit cultural and historical baggage, from its self-conscious antiquarian roots in late medieval ballads to its engagement with more currently pressing concerns of environmentalism and how