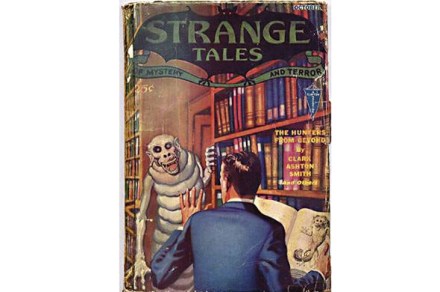

‘Level’ has a bumpy history

‘I must level with you, level with the British public, many more families are going to lose loved ones.’ That is what Boris Johnson said on 20 March last year. On 14 May this year, he said: ‘I have to level with you that this new variant could pose serious disruption.’ In between, the Prime Minister often spoke of levelling up. He even got the Queen at it, in her ‘Most gracious speech’, as it is formally called: ‘My government will level up opportunities across all parts of the United Kingdom.’ Mr Johnson explained how that is done: ‘These new laws are the rocket fuel that we need to level