Object lesson | 3 August 2017

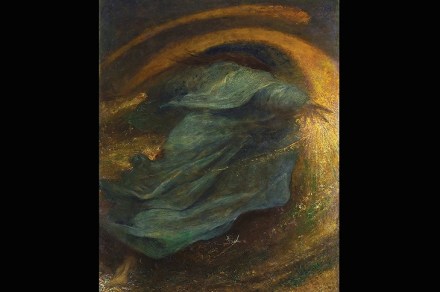

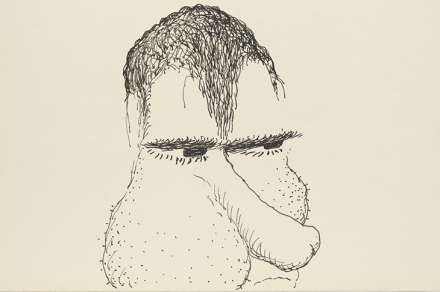

Why did Henri Matisse not play chess? It’s a question, perhaps, that few have ever pondered. Yet the great artist provided an answer, which is quoted in the catalogue to Matisse in the Studio, a marvellous new exhibition at the Royal Academy. He did not care, he explained, ‘to play with signs that never change’. It’s a revealing reason in several ways. For one thing, it underlines how different Matisse was from his younger contemporary Marcel Duchamp: the most celebrated chess-player in art. Duchamp loved logic, so his work tended to turn into a series of theorems. Matisse, in contrast, lived and worked in a beautiful muddle, surrounded by clutter