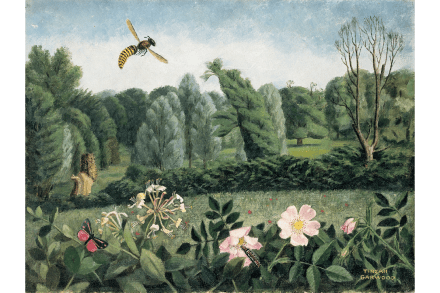

Tirzah Garwood just isn’t as good as her husband

Tirzah Garwood, wife of the more famous Eric Ravilious, is having a well-deserved moment in the sun, benefiting from this era of equality in which artists’ and composers’ wives and sisters (such as Clara Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn and Elizabeth Siddal) are having the spotlight shone on their under-appreciated works. It’s not profound art but it’s a pleasure to look at, created to delight all ages Garwood is not quite as good as Ravilious, in the same way that Clara and Fanny are not quite as good as Robert and Felix, but she is nonetheless a pleasure to encounter, with an infectious, playful delight in everyday sights of her time, such