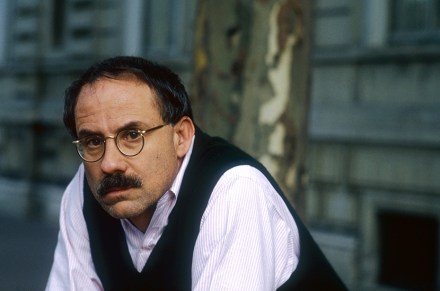

Glasgow gangsters: 1979, by Val McDermid, reviewed

Like a basking shark, Val McDermid once remarked, a crime series needs to keep moving or die. The same could be said of crime writers themselves, who work in a genre that has an inbuilt tendency to encourage repetition, often with dreary results in the long term. McDermid herself, however, has a refreshing habit of rarely treading water for long. Over the past 34 years, she’s published four very different crime series, a clutch of standalones, two books for children, a modern reworking of Northanger Abbey, and several non-fiction titles. And now comes 1979, the first in a planned five-book series set at ten-year intervals up to the present. It’s