The pleasure of reading Rumer Godden’s India

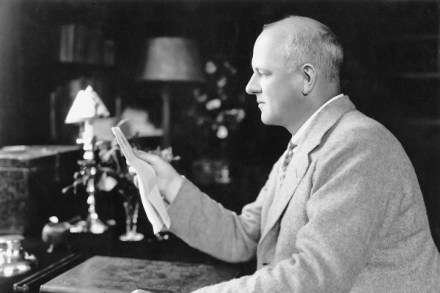

Rumer Godden’s prose tugs two ways at once. It is subtle, descriptive, and light, but also direct and unashamed of being turned inside out until darkness consumes it, rendering what was beautiful irrelevant and suddenly opaque. There is also a lot of it. Rumer Godden OBE (1907-1998) wrote over sixty works of fiction and non-fiction over a lifetime divided between England, where she was born, India, where she spent much of her young adulthood, and Scotland, where she lived for the last twenty years of her life. Godden’s three best-known novels, Black Narcissus, Breakfast with the Nikolides, and Kingfishers Catch Fire are set in India. Flickering with the awe and