The death of cosy Christie

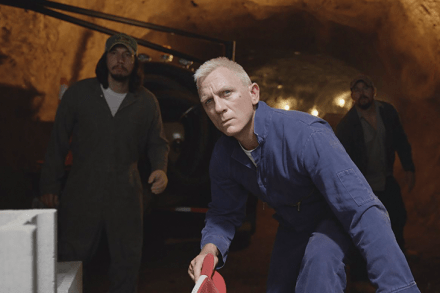

This is not Midsomer Murders. The new film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is thick with violence and sexual innuendo. It elevates Hercule Poirot, the diminutive, fastidious Belgian detective, with his egg-shaped head and pot belly, to part-time action figure, a man who chases bad guys down dizzying descents in exotic snowscapes before straightening his magnificent moustache with a twinkle in his eye. This is less cosy, golden age detective fiction than a cross between Daniel Craig’s 007 and Scandi noir. Kenneth Branagh, who stars and directs, has brought his experience playing the dejected Swedish police inspector Wallander to the fore, giving the usually reserved detective