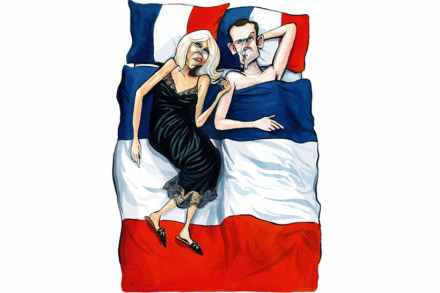

France is getting fed up with Brigitte Macron

Having recently hosted Bono and Rihanna and taken centre stage during Donald Trump’s visit to France, Brigitte Macron now has a new role to keep herself busy. The French President’s wife was named last week as the godmother of the first baby panda born in a French zoo. Macron said she was ‘very happy’ to be asked. But, increasingly, France is not feeling her joy and there is growing resentment at her presence in the Élysée Palace. An online petition launched two weeks ago by the artist Thierry Paul Valette opposing the creation of a formal role for Brigitte Macron as First Lady has been signed by nearly 200,000 people. The petition says