I was dreading this show – how wrong could I be: Entangled Pasts, at the Royal Academy, reviewed

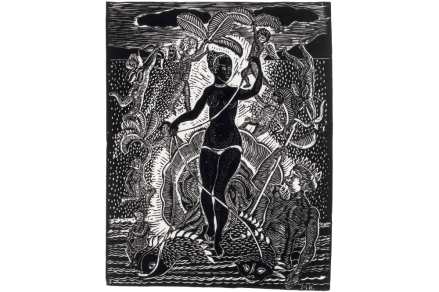

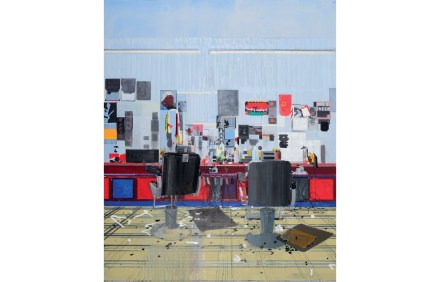

In the wake of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition Black Atlantic about its founder’s ties to the slave trade comes the Royal Academy’s Entangled Pasts, less of a mea culpa than an examination of conscience by an institution which, although hailed by its first president Sir Joshua Reynolds as an ‘ornament’ of Empire, was innocent of direct links to slavery. The exhibition is less of a mea culpa than an examination of conscience I confess that I was rather dreading this show, which sounded from the pre-publicity like a hollow exercise in Britannia-Rules-the-Waves breast-beating, but from the moment I stepped into the courtyard and saw the posturing Sir Joshua on his