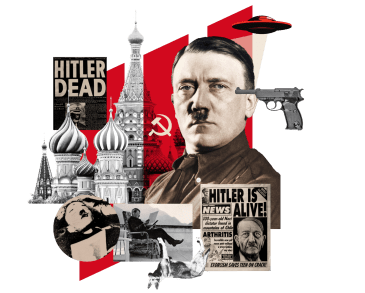

The race against Hitler to build the first nuclear bomb

Ettore Majorana vanished in March 1938. According to Frank Close in Destroyer of Worlds, the 31-year-old Sicilian physicist ‘probably understood more nuclear physics theory than anyone in the world’, and was hailed by Enrico Fermi as a ‘magician’, in the elevated company of Newton and Galileo. Majorana was also an ardent fascist; yet he was haunted by the destructive potential of his work on mapping the nucleus. His disappearance – perhaps a suicide; more likely a new, incognito life in South America – has been related to an anguished remark he made to a colleague: ‘Physics has taken a bad turn. We have all taken a bad turn.’ Majorana is