French baiting from the PM?

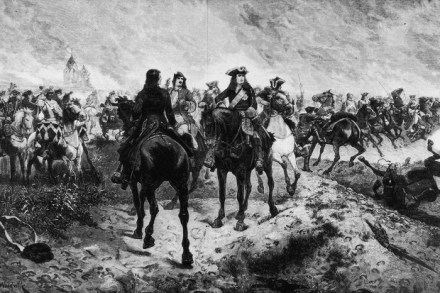

The French media might prostrate themselves before their own leaders; but they are a little more adventurous with ours. Le Figaro reports that the original plan for today’s Anglo-French Summit at RAF Brize Norton, followed by a pub lunch, was to have been a far grander affair. Hollande was to be invited to Cameron’s constituency and then on to nearby Blenheim Palace. But French officials reportedly pointed out that the Duke of Marlborough’s home was so named in honour of his ancestor’s crushing defeat of the Franco-Bavarian army at Blenheim in 1704. The French suffered 30,000 casualties and the battle was a turning point in the War of the Spanish