Go out and govern New South Wales

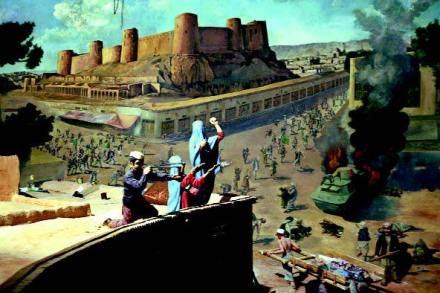

‘In the mists and damp of the Scottish Highlands, 61-year-old Sir Bartle Frere was writing a letter. ‘In the mists and damp of the Scottish Highlands, 61-year-old Sir Bartle Frere was writing a letter. Straight-backed, grey-haired, he had the bright eye and bristled moustache of an ageing fox-terrier.’ Reading this, at the beginning of a chapter, we cannot be sure whether what follows will be Lytton Strachey or John Buchan. The tale might go either way. The letter might be either an invitation to shoot grouse or in answer to a summons to cope with a crisis threatening the British empire. The second guess would be right. The letter was