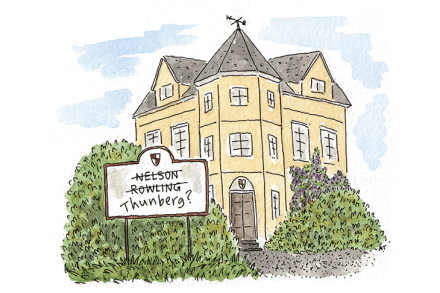

Tacitus and the hypocrisy of cancel culture

The delicious hypocrisy at the heart of today’s cancel fraternity is that it is strongly opposed to censorship. Romans grappled with the issue; the historian Tacitus nailed it. Since the Roman republic sprang from the expulsion of a tyrant-king (509 bc), anti-monarchic views became standard fare in legal and political debate whenever anyone suspected tyranny. Julius Caesar, seen by some, and slain, as a tyrant, was well aware of such republican sympathies and ‘bore with good nature’ abuse of himself. So did his successor Augustus (27 bc). True, he ended publication of senatorial minutes, but senators still had their say. Vitriolic pamphlets directed against him were initially met with written