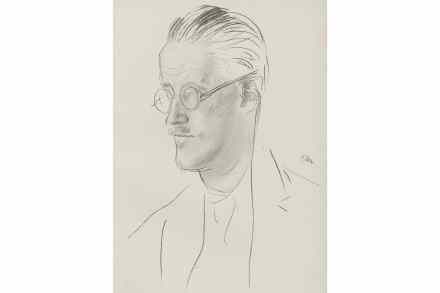

The mystifying cult status of Gertrude Stein

To most people, the salient qualities of Gertrude Stein are unreadability combined with monumental self-belief. This is the woman who once remarked that ‘the Jews have produced only three original geniuses – Christ, Spinoza and myself’. Of the reading aloud of her works, Harold Acton complained: ‘It was difficult not to fall into a trance.’ Even if you are as good a writer as Francesca Wade, it is still difficult to avoid the influence of what she herself calls Stein’s ‘haze of words’. So the first half of this impressively researched biography is cerebral rather than colourful. Stein’s writing career really began when, aged 28 (she was born in 1874),