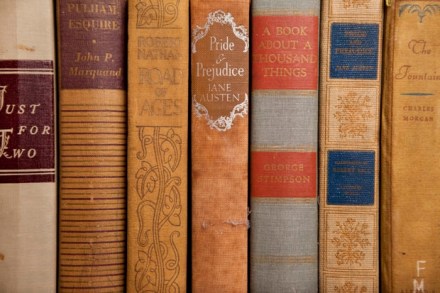

A few good books

It is a truth universally acknowledged that whenever ITV or the BBC decides — the latter usually with charter renewal in the near or middle distance — that it needs to make some of that World-Class Drama it’s so proud of, its thoughts turn to regency frocks, scruffy urchins, pea-soupy London, agreeable country houses and the incessant clip-clop of hoof on cobble. Classy costume drama — invariably based, for extra classiness, on classy fiction of the sort you might find in Penguin Classics — is one of our major exports. But in the range of its source material they consider, its makers are as blinkered as the inevitable horse that