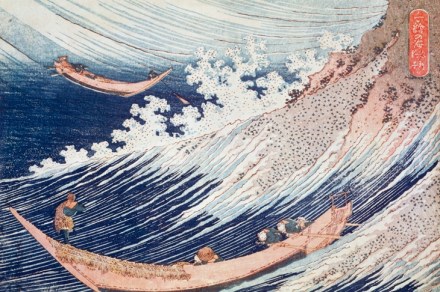

Big in Japan

An early morning in late November in the peaceful glades that surround an ancient temple complex. A Shinto priest in sombre silks slips through a sliding door; a maple leaf catches the breeze. Suddenly, the silence is broken by the crunching thwack as two 400lb slabs of prime meat collide. It is the 15th and final day of one of Japan’s six annual sumo tournaments: the Kyushu Basho, held every autumn in the balmy southern city of Fukuoka. A group of visiting wrestlers have begun their pre-breakfast workout in one of the outbuildings of Torikai Hachiman-gu, preparing for the afternoon bouts at the arena three miles away. Sumo is as