‘A group of deranged idiots’ – how the Soviets saw the Avant-Gardists

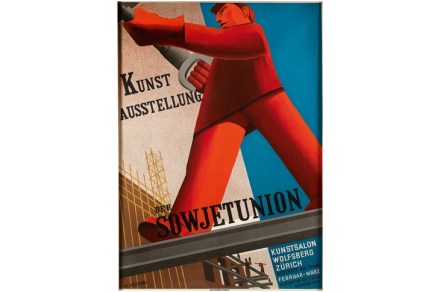

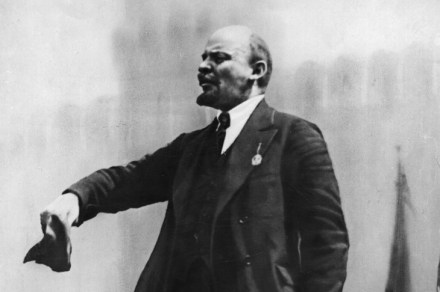

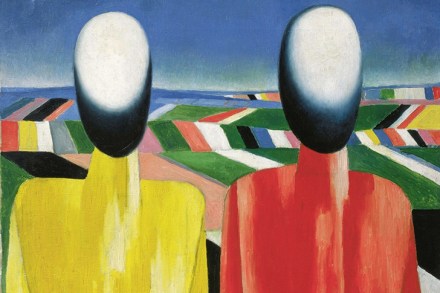

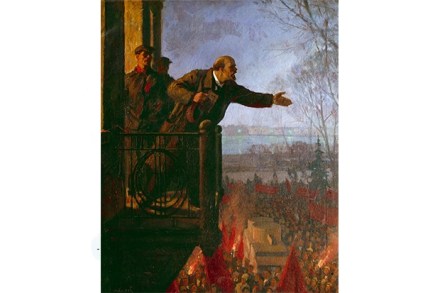

The Avant-Gardists tells the story of the small group of brilliant, punky outsider artists who, after the Bolshevik coup in 1917, to everyone’s amazement suddenly found themselves holding important posts in government (as if Sid Vicious were made minister of education). They were soon demoted, and by the end of the 1920s persecuted or driven abroad. Yet news of their breathtaking originality spread internationally, playing an important role in transforming not only our understanding of art, but the aesthetics of modern life, from buildings to household objects, textiles to the printed word. Sjeng Scheijen has written an exhilarating history of the movement, illuminated by new research and insights, and with