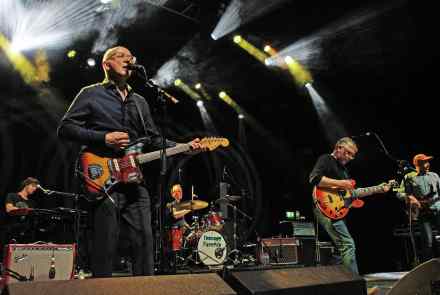

The quiet radicalism of the Chieftains

Pop quiz time: which act was named Melody Maker Group of the Year in 1975? The answer is not, as you might expect, some testosterone-fuelled blues-rock outfit or a hip gang of proto-punk gunslingers, but a gaggle of semi-professional Irish musicians who performed trad tunes sitting down, dressed for church in cardigans, sensible shoes, shirts and ties. The Chieftains were so far from rock and roll they met it coming back the other way. On the cover of Irish Heartbeat, a later collaboration with Van Morrison, they could be mistaken for a loose affiliation of farmers, minor office clerks and earnest ornithologists waiting for a bus outside the town hall.