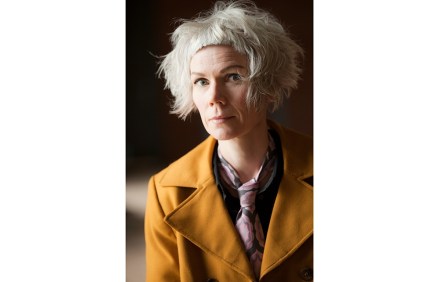

Joan Collins, Owen Matthews, Sara Wheeler, Igor Toronyi-Lalic and Tanya Gold

30 min listen

On this week’s Spectator Out Loud: Joan Collins reads an extract from her diary (1:15); Owen Matthews argues that Russia and China’s relationship is just a marriage of convenience (3:19); reviewing The White Ladder: Triumph and Tragedy at the Dawn of Mountaineering by Daniel Light, Sara Wheeler examines the epic history of the sport (13:52); Igor Toronyi-Lalic looks at the life, cinema, and many drinks, of Marguerite Duras (21:35); and Tanya Gold provides her notes on tasting menus (26:07). Presented and produced by Patrick Gibbons.