The traditional British hedge is fast vanishing

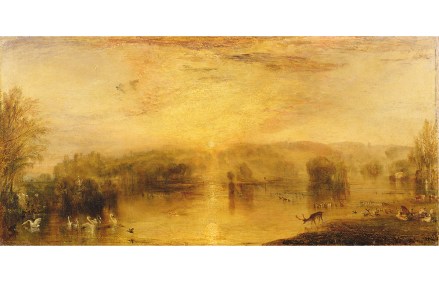

Five years ago, a documentary about the Duchy of Cornwall featured the then Prince of Wales in tweeds and jaunty red gauntlets laying a hawthorn hedge. It was a brilliant piece of PR. If Charles was a safe pair of hands with a hedge – something as quintessentially English as a hay meadow or a millpond – he was surely a safe pair of hands full stop. A cuckoo in one breeding season needs to eat about 22,500 hairy caterpillars Focusing on a hedge in south-west Wiltshire, Hedgelands combines history, celebration, lament and warning. Christopher Hart is a companionable writer, and makes a powerful case that, at a time of