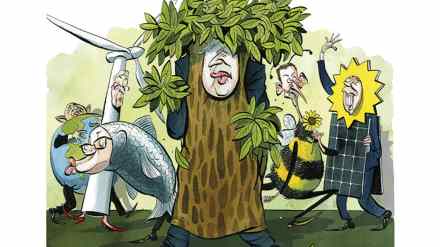

The boiler ban fiasco and the true cost of net zero

Politically it must have seemed an easy promise for Theresa May to make in the dying days of her premiership: to commit Britain to a legally-binding target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050, rather than the 80 per cent reduction previously stipulated in the Climate Change Act. It was the summer of 2019 and Extinction Rebellion protests had taken place with surprisingly little counter-protest. David Attenborough’s TV documentary was received warmly by the press, and polls indicated that the public appeared to supported action on climate change – according to a YouGov poll in December 2018 two thirds of the population stated they did not believe the risks of