Building block | 8 June 2017

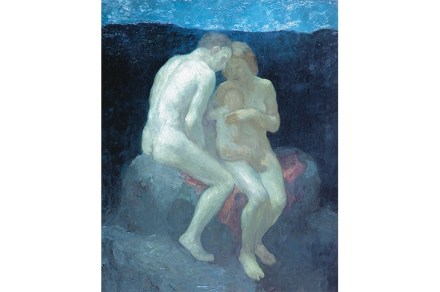

Liverpool is the New York of Europe. The business district looks like old Wall Street: a miniature Lower Manhattan on the Mersey. It’s a city of scale, drama, melodrama, tragedy and comedy. Not to mention rich and poor. And often all these effects are simultaneous. No other British city has a similarly contrary architectural character: superb, shabby, romantic, melancholy, proud and mean. You cannot be in Liverpool and not be affected by its buildings. I grew up there and long before I knew what ‘design’ meant, Liverpool had taught me to see — as well as to feel the deadly weight of history. It’s an architectural education. But Liverpool has