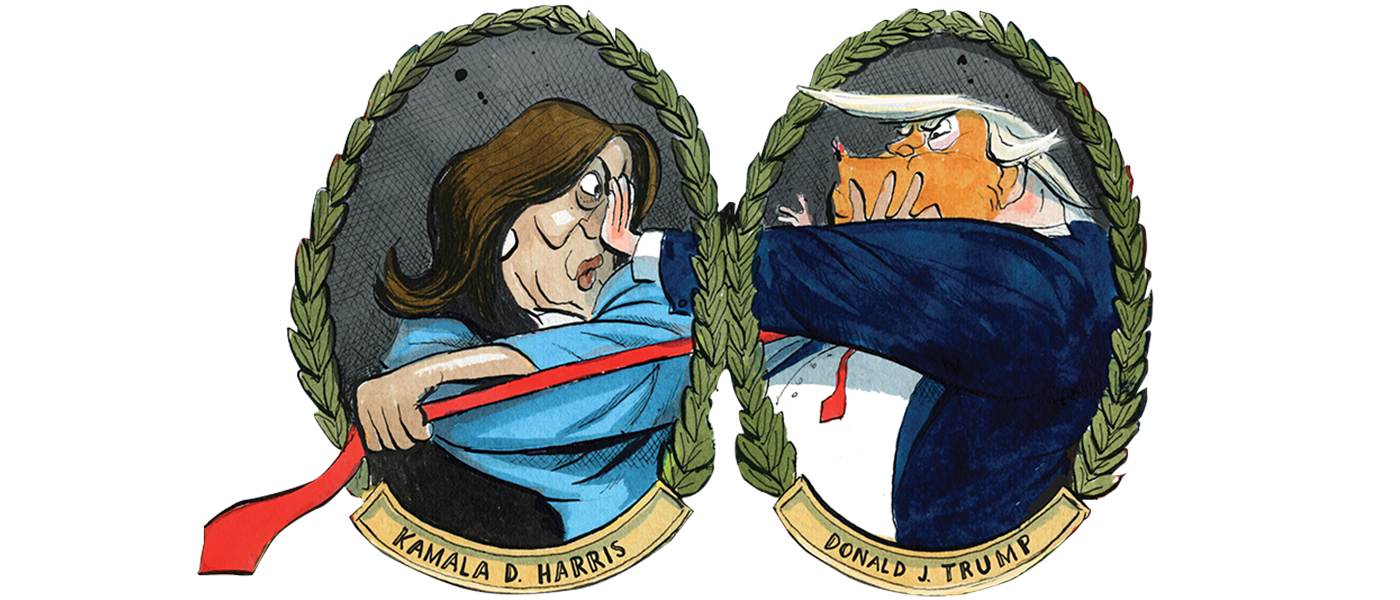

A gimlet eye

We should be grateful to families which encourage the culture of writing letters, and equally vital, the keeping of them. Leopold Mozart, for instance, taught his son not only music but correspondence, and as a result we have 1,500 pages of letters which tell us everything we know of interest about the genius. His younger contemporary Jane Austen also came from a postman’s knock background. We have 164 of her letters, from January 1796, when she was 21, to the eve of her death in 1817. Some have been cut by the anxious family, and some suppressed altogether, but the remainder are pure gold. As in her novels, she never