The orchestra that makes pros go weak at the knees

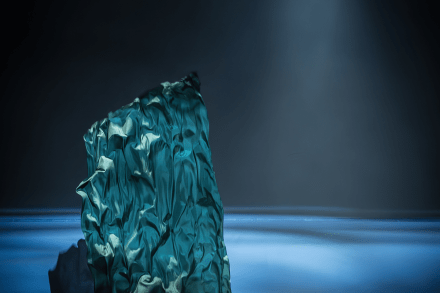

Stravinsky’s The Firebird begins in darkness, and it might be the softest, deepest darkness in all music. Basses and cellos rock slowly, pianissimo, in their lowest register; using mutes to give the sound that added touch of velvet. Far beneath them rumbles the bass drum: a halo of blackness, perceptible only at the very edge of the senses. In Liverpool Philharmonic Hall, with Sir Simon Rattle conducting the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, you felt your hairs tingle before you discerned a note. Seconds later, the very air within the hall seemed to be quivering with sensuous, engulfing bass warmth. You can be sure that Rattle anticipated that sensation; planned for